Ditches and moats, another tool borrowed from horse and cattle breeders, offered twelfth-century military architects a more durable curtaining wall for their field fortifications. Because they were intended to halt or hinder the advance of mounted troops, rather than keep hordes of attacking infantry at bay, such ditches needed to be only a few meters wide or deep, and were usually dry. Many were topped on the inner side with earthen ramparts constructed from the dirt removed to dig the trench.

Among the most remarkable examples of early medieval military ditches is the massive defensive line Fujiwara Yasuhira prepared when he learned of Yoritomo’s invasion plans in 1189. This barrier, the remains of which can still be seen today, effectively blocked the whole of the Tosando, the only route into Mutsu. Stretching some 3 kilometers between Azukashiyama and Kunimishuku, on the northeast end of the Fukushima plain, it was about 15 meters wide and 3 meters deep, featuring steep ramparts of packed earth, augmented here and there with stone. Yasuhira also set up a secondary line some 20 kilometers behind this, and stretched ropes across the Natori and Hirose rivers to form a tertiary line 30 kilometers behind that.

The line of walls constructed along the coastline of northern Kyushu, as a defense against the Mongol invasions of the late thirteenth century, was even grander. Composed of earth, granite and sandstone, and standing 2 to 3 meters high and equally wide, it stretched nearly 10 kilometers.

Fortifications of this scale required enormous labor resources. Manpower costs for Yasuhira’s Azukashiyama ditch have, for example, been calculated at more than 20,000 working days. Thus, even mobilizing the entire adult peasant population of the neighboring three districts – at the time, about 5,000 men – the project would have taken forty days or more to complete. Workers for military construction projects were usually conscripted locally, on the basis of various tax obligations.

Ditches and dry moats, augmented with sakamogi or earthen ramparts, were more than adequate barriers against Japanese ponies. Unlike European or later medieval Japanese castles, moreover, twelfth-century jokaku did not trap the defenders inside, and therefore constituted only a part of the strategy underlying the battles and campaigns in which they were deployed. Indeed, the construction and use of barricades was intimately bound up with the question of how and when to throw one’s own mounted troops at the enemy. Warriors waited behind the walls for the right moment to charge out and counter-attack, or to withdraw to secondary or tertiary lines.

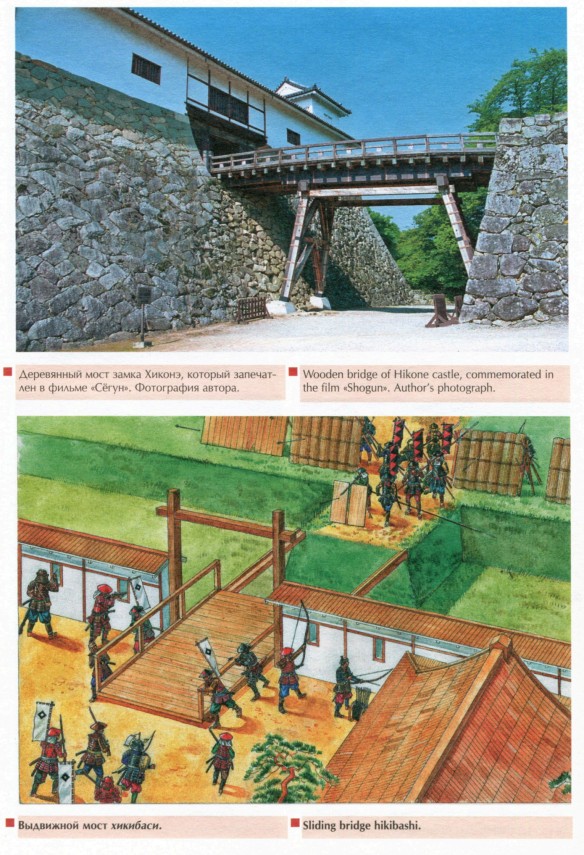

Wooden gates (kido or kidoguchi), through which defenders on horseback could rush forth to assault besieging forces, constitute the one ubiquitous feature of late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century fortifications. As the only points at which mounted warriors – of either side – could readily cross the barricades, they were usually the nodal points of battle. Consequently, they were the most heavily defended parts of the line, flanked by one or more shielded platforms (yagura, literally, “arrow stores”) from which archers could shoot down at approaching troops.

On occasion, attacking armies mobilized laborers to build counterfortifications or dismantle enemy barricades. In the Mutsu campaign, for example, Yoritomo set eighty men, under Hatakeyama Shigetada, to hauling rocks and earth with plows and hoes in order to fill in parts of the Azukashiyama ditch, so that his horsemen could cross. But while the sheer size of the Azukashiyama ditch, and of Yoritomo’s army, made counter-mining operations practical and necessary, against less extensive – and more densely defended – fortifications this tactic would have exposed the workers and their supervisors to rocks and arrows launched from the ramparts. Similarly, bushi who dismounted to scale the walls of the trench made themselves vulnerable to horse-borne counter-offenses, or made it easier for the defenders to withdraw and escape. More commonly, therefore, warriors confronting fortifications focused on storming the entrances and on flanking attacks.

The architectural features, and the tactical considerations, that governed Kamakura-period fortifications continued to dominate the fortresses and skirmishes of the Nambokucho era as well. But the battles of the 1330s also introduced a new role for warrior strongholds, new kinds of fortresses, and new forms of siege warfare.

During the eighth month of 1331, Go-Daigo fled the capital and “reestablished his imperial abode” in Kasagi temple, on the border between Yamato and Yamashiro. There he speedily erected fortifications and began sending out calls to arms. In response, the shogunate dispatched Sasaki Tokinobu, in command of troops from Omi and reinforced by 800 horsemen under the Kuge and Nakazawa families of Tamba, to capture him. On the first day of the ninth month, as 300 outriders from this force, under Takahashi Matashiro, approached the foot of Mount Kasagi, they were ambushed and routed by the castle garrison. Concerned that “should rumors spread of how [the shogunate’s men] lost this first battle, and how the castle was victorious, warriors of the various provinces would gallop to assemble there,” Kamakura promptly sent a massive army – nearly 75,000 men, according to Taiheiki – to invest the castle.

At dawn, on the third day of the ninth month, this force assaulted Kasagi “from all directions.” But the castle defenders fought back fiercely, showering the attacking troops with rocks and arrows such that:

Men and horses tumbled down one upon another from the eastern and western slopes surrounding the castle, filling the deep valleys and choking the roads with corpses. The Kozu River ran with blood, as if its waters reflected the crimson of autumn leaves. After this, though the besieging forces swarmed like clouds and mist, none dared assail the castle.

While the shogunal leaders stood at bay in front of Kasagi castle, “which held strong, and did not fall even when attacked day and night by great forces from many provinces,” to their rear other imperial loyalists were “raising large numbers of rebels, and messengers rushed to shogunal headquarters daily”:

On the eleventh day of that month, a courier was dispatched from Kawachi, reporting that, “Ever since the one called Kusanoki Hyoe Masashige raised his banner in service of the Emperor, those with ambitions have joined him, while those without ambition have fled to the east and west. Kusanoki has impressed the subjects of his province, and built a fortress on Akasaka mountain above his home, which he has stocked with as many provisions as he could transport, and manned with more than 500 horsemen. Should our response lag, this must become a troublesome matter indeed. We must direct our forces toward him at once!” . . .

Meanwhile, on the thirteenth day of that month a courier was dispatched from Bingo, with the message that, “The lay monk Sakurayama Shiro and his kinsmen have raised imperial banners, and have fortified [Kibitsu] shrine of this province. Since they have ensconced themselves within it, rebels of nearby provinces have been galloping to join them. Their numbers are now more than 700 horsemen. . . . If we do not strike them quickly, before night gives way to day, this will become an immense problem.”

Go-Daigo’s loyalist followers looked to fortifications not just as tactical barricades – devices for focusing battles, delimiting campaigns, or trammeling enemy horsemen – but as rallying points, sanctuaries, and symbols of resistance. Thus, while most twelfth- and thirteenth-century defense works had been constructed across or adjacent to roads, beachheads and other travel arteries, Kusanoki Masashige and his allies ensconced themselves in remote mountain citadels, whose purpose and presence defied Kamakura authority, and served as a beacon to other recruits.

Descriptions in Taiheiki and other texts, and depictions of fortifications in fourteenth-century scroll paintings, indicate that fortresses of the period were architecturally similar to those of the early Kamakura era, albeit now fully enclosed and often reinforced with wooden palisades and additional yagura erected at various points along the walls between, as well as adjacent to, the gates. The latter two innovations were a necessary consequence of the first. For, unlike the easily abandoned defensive lines favored by twelfth- and thirteenth-century warriors, the citadels Kusanoki and his compatriots occupied allowed the defenders no rapid means of escape or retreat. Indeed, they invited encirclement and siege, beckoning enemy horsemen – hitherto stymied by trenches and simple earthworks – to dismount and assault the walls directly.

Compact enough to be easily defended on all exposures, and located on terrain sufficiently treacherous to render them difficult to approach quickly or in large numbers, such citadels were not readily taken by direct onslaught – even if besieging forces did not really have to contend with the collapsing sham walls, decoy armies of mannequins, and other imaginative slight-of-hand tactics Taiheiki attributes to Kusanoki Masashige. More often, it seems, mountain castles fell to attrition – sometimes hastened by cutting off the garrison’s water or food supplies. Others were captured by infiltration or stealth.

In this way, relatively small numbers of warriors could tie up sizeable enemy forces for long periods, buying time and credibility for Go-Daigo’s cause, and whittling away at the morale of Kamakura’s troops. Kusanoki’s garrison of “more than 500 warriors” on Mount Akasaka in 1331 held “what looked to be a hastily-devised” fort “less than one or two hundred meters across” for nearly three weeks, against a shogunal army allegedly comprising “more than 20,000 horsemen.” In 1333, he held Chihaya castle near Mount Kongo in Kawachi for more than two months, while a besieging force “rumored to have been over 800,000 horsemen at the beginning” of the siege dwindled to “scarcely 100,000 riders.”