When British naval intelligence determined that a large number of Italian warships lay at anchor in Taranto harbour in November 1940, an attack was organized, to be carried out by 21 single-engine carrier-based biplanes. The operation was a huge success — three battleships were severely damaged, a cruiser and two destroyers were hit, and two other vessels were sunk. In the space of one hour the balance of naval power in the Mediterranean had been altered forever.

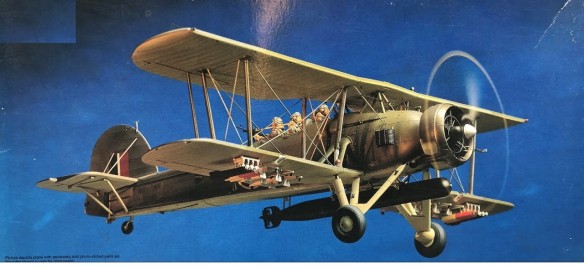

The unlikely cause of this destruction was one of the warplane legends of World War Two, the Fairey Swordfish Mk.1, first flown on 17 April 1934. It was a three-man torpedo-bomber and reconnaissance biplane with a basic structure of fabric-covered metal. The wings folded for storage on the crowded deck of an aircraft carrier. Armament included one forward-firing Vickers machine gun and one swivelling Vickers in the rear cockpit. Primary offensive power took the form of depth charges, mines, bombs or, especially, a torpedo.

Unfortunately, this outstanding plane was too slow to withstand the punishment of German anti-aircraft fire. Long, accurate approaches to the target made the Swordfish very vulnerable when delivering its torpedo. Thus came re-deployment in an anti-submarine warfare role, using depth charges and, later, rockets.

As with many wartime aircraft, Swordfish were produced by more than one manufacturer. Well over half (almost 1700) were built by the Blackburn company in Sherburn in Elmet, UK.

The Mk II model was introduced in 1943, and featured strengthened and metal-skinned lower wings to allow the firing of rockets from underneath. Later that year, the Mk III appeared, which featured a large ASV anti-submarine radar unit mounted between the landing gear legs which allowed detection of submarines up to 40 km away. For operation over the cold waters of Canada, the Swordfish Mk IV was fitted with an enclosed cabin.

When production ended in 1944, the Swordfish had had been introduced into a full range of duties for the fleet: Torpedo-bomber, minelayer, convoy escort, anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft and training craft. Today, four Swordfish are airworthy — two in Britain and two in Canada.

Taranto 1940

During the night of 11-12 November, two waves of Swordfish aircraft from the carrier Illustrious had the temerity to attack the Italian Fleet as it lay at anchor in harbour at Taranto, crippling three of its battleships while slightly damaging a heavy cruiser and a destroyer into the bargain. Everyone on the British side was delighted with the results of Operation Judgment, since it appeared to have eased the Allied naval position in the Central Mediterranean, by reducing the risks to their convoy traffic and boosting morale in their own ranks, while complicating the Italian strategic situation and deflating the enemy. Cunningham summed up the cost-benefit analysis of the entire operation perfectly by stating: `As an example of “economy of force” it is probably unsurpassed.’ He was not prone to exaggeration and his enthusiasm for taking the fight to the Italians was infectious.

The first carrier-based aircraft strike against a fleet of warships. Located on Italy’s eastern coast, Taranto was the main Italian naval base in early World War II. The excellent natural harbor comprised two anchorages-Mare Grande and Mare Piccolo. When Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940, its sizeable Mediterranean fleet became a threat to the British, who were fighting alone following the fall of France that May.

The Axis envisioned this fleet controlling the Mediterranean shipping lanes and reducing supplies to British forces in North Africa. Concurrently, the Royal Navy sought to engage and destroy the Italian fleet to limit the resupply of Erwin Rommel and the Afrika Korps. To this end, Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, commander in chief Mediterranean, sent British ships near the Italian coast to lure (without success) the Italians into a surface engagement.

British intelligence reported that increasing numbers of large ships were congregating at Taranto. Thus, Cunningham ordered his operational commander to plan an airborne carrier attack for 21 October 1940-Trafalgar Day.

Originally, the HMS Eagle and the new HMS Illustrious were to launch the attack. However, a fire aboard Illustrious delayed the operation until 11 November-Armistice Day. Additionally, Eagle suffered bomb damage and was removed from the operation. Some of its aircraft were transferred to Illustrious.

At 8:40 P. M. 11 November, Illustrious launched 12 old and slow Swordfish biplanes of the Nos. 813 and 815 Squadrons 170 miles southeast of Taranto. Fourteen Fulmer and four Sea Gladiator fighters of No. 806 Squadron flew air cover. Two Swordfish carried flares and four carried bombs. This first group arrived over the target at 11:00 P. M. and illuminated the harbor with the flares; the aircraft armed with bombs made a diversionary attack on the cruisers and destroyers.

The last six Swordfish in the first wave, armed with one torpedo each, attacked the six Italian battleships anchored at Mare Grande. A single torpedo put a hole in the Conte di Cavour, which began to sink. A second torpedo tore a hole in the Caio Duilio, which was run aground in shallow water. The first wave lost one plane; the crew survived.

Less than an hour later, as Italian crews were fighting fires and searching for shipmates, a second wave of nine Swordfish from Nos. 819 and 824 Squadrons struck. Five of the planes had torpedoes. This time the Littorio was heavily damaged and also run aground. A second torpedo hit the Cavour, sending it to the bottom in deep water. Numerous lesser ships were also damaged. The second wave lost one plane; both crew members were killed.

In one night, the British had taken a major step in wresting control of the Mediterranean from the Axis. The remainder of the Italian fleet soon withdrew to Naples on the western coast and out of range of British carrier planes. The Cavour took enormous resources to refloat and never returned to service. The other two were refloated in two months, but it took many more months to make them seaworthy. By that time the Italian navy was less of a factor. Cunningham noted that after Taranto the Italian fleet “was still a considerable force” but had been badly hurt.

Although some historians remain unconvinced, there is evidence that Britain’s Taranto air attack inspired Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto to launch the 1941 carrier-based air attack on Pearl Harbor. Regardless, at Taranto a single British carrier and 21 antiquated biplanes crippled the Italian fleet in one nighttime raid, proving the vulnerability of surface vessels to aerial assault.

Stringbags versus Bismarck

Bismarck continued making for refuge at Brest, the only choice she now had with reduced speed and heavy fuel loss, but the Royal Navy wasted time searching in the opposite direction on the assumption that she had probably turned back. She was eventually sighted at 1030 on the 26th by a Coastal Command Catalina, which was driven away by heavy AA fire. However, two Swordfish of No. 810 Squadron had been sent up at 0840 by Ark Royal, which was now on the scene, and at 1114 the enemy was sighted again, ‘2H’, piloted by Sub-Lt(A) J. V. Hanley RN with Sub-Lt(A) P. R. Elias RNVR and L/ H. Huxley, being joined seven minutes later by ‘2F’, flown by Lt(A) J. R. . Callander RN with Lt P. E. Schonfeldt RN and L/ R. V. Baker. These two aircraft then maintained contact until relieved by another pair, landing aboard at 1324. This tactic continued until late that night, despite extremely severe weather.

In terrible conditions fourteen Swordfish took off from Ark Royal at 1450 with instructions to attack, though with some doubt at that time as to whether the enemy warship sighted was in fact Bismarck or Prinz Eugen. What occurred next is described in Ark Royal’s subsequent report

‘The weather conditions were particularly bad over the target area when the striking force took off … reliance was therefore placed in the ASV set carried in one of the aircraft which located a ship 20 miles from the position given the leader on taking off. This happened to be the Sheffield who had been sent to shadow the enemy from astern. On getting over the supposed target an attack through the clouds was ordered and before many of the pilots ‘knew what they had done. 11 torpedoes had been dropped at the Sheffield. Fortunately, in one sense, 50 per cent of the Duplex pistols fired prematurely, the remainder were dodged by the Sheffield who increased to high speed.’

The presence of Sheffield was unknown to Ark Royal owing to a delay in the deciphering of a signal, but fortunately the cruiser’s Captain had skilfully succeeded in evading the torpedoes launched by eleven of the aircraft. The mistake having been recognized, a second strike was launched at 1910 with fifteen aircraft comprising four each of Nos 810 and 818 Squadrons and seven of No 820, led by Lt Cdr T. P. Coode RN, the CO of No 818. They formed up in squadrons of two sub-flights each, in line astern, taking departure over the battlecruiser Renown at 1925. The weather had improved somewhat, and 1 1/2 hours later contact was made first with Sheffield to help locate the target, and also to ensure that she herself did not again become the target. The force then climbed to 6,000ft. Conditions near Sheffield were reported as ‘Seven-tenths cloud from 2,000 to 5,000 feet; conditions ideal for torpedo attack’. The force then climbed to 6,000ft but temporarily lost contact with Sheffield while in cloud. Regaining contact at 2035, the crew were told that the enemy was twelve miles away on bearing 110*. Five minutes later they headed for the target in sub-flights in line astern at a ground speed of 110kts, but while the cloudy conditions through which they then climbed greatly assisted surprise, they made it difficult for the sub-flights to keep in contact with each other. Heavy fire was now encountered, forcing some of the aircraft to turn away initially, but all succeeded in dropping their torpedoes.

The final dive and approach began at 2053, and No 1 Sub-Flight was shortly followed by an aircraft of No 3 Sub-Flight which joined them in an attack from the port beam. This aircraft observed a hit two-thirds of the way forward on the enemy vessel. All four aircraft came under intense and accurate AA fire from the moment of first sighting until making their getaway downwind. No 2 Sub-Flight climbed to 9,000ft in cloud but lost contact with No I. Ice began to form on the wings, but the dived down on an ASV bearing. The third aircraft of this sub-flight, ‘2P’, piloted by Sub-Lt(A) A. W. D. Beale RN, completely lost touch in the cloud but returned to Sheffield and obtained a fresh range and bearing, then carried out a solo attack from the port bow under very heavy fire, and he and his crew had the satisfaction of seeing their torpedo hit Bismarck amidships.

Meanwhile No 3 Sub-Flight of two aircraft had gone into cloud, closely followed by No 4. Again, however, contact was lost, but ‘2M’ of No 3 Sub-Flight somehow managed to join up with No 4 Sub-Flight as they dived into a clear patch at 2,000ft, and they circled the enemy astern before diving through a low piece of cloud for a simultaneous attack from the battleship’s port side. As with previous aircraft, they attracted very fierce fire, which continued until they were seven miles away. Aircraft ‘4C’ was hit 175 times, both the pilot and air gunner being wounded though the observer was unscathed.

No 5 Sub-Flight, of two aircraft (‘4K’ and ‘4L’), followed the others into cloud but soon lost them and each other. They continued climbing into cloud until ice started to form at 7,000ft, when they started to descend, but while still in cloud ‘4K’ encountered AA fire. He came out of cloud at 1,000ft, sighted the enemy downwind and went back into cloud to work round to a position on the starboard bow, seeing a torpedo hit the starboard side while doing so. After withdrawing to about five miles, he then came in and dropped his torpedo at a range of just over 1,000yds. Aircraft ‘4L’, having completely lost contact, dived through a gap in the clouds from 7,000ft and, seeing no other Swordfish, made two attempts to close, but he met such intense and concentrated fire that he had no choice but to withdraw, jettisoning his torpedo before returning to the carrier.

Similar conditions were met by No 6 Sub-Flight, which had also returned to Sheffield for a fresh range and bearing: ‘4G’ managed to drop at 2,000yds, but ‘4F’ also had to jettison. Despite damage to many of the aircraft, all returned to the carrier and only two air crew were wounded. Bismarck had been hit aft, and such severe damage was caused to her propellers and rudders that she could only maintain a slow speed and was almost unmanoeuvrable. At 2325 hadowing aircraft reported her turning lowly in circles and. he was subsequently reduced to a burning wreck by gunfire from Royal Navy capital ships. A third air strike took off at 0915 next morning in bad weather. The target was sighted at 1020, but before the crew could launch their missiles they saw torpedoes from the cruiser Dorsetshire hit her and then watched the battle hip capsize to port and founder. The Swordfish jettisoned their own torpedoes and returned to the carrier. Prinz Eugen managed to get through to Brest, where she joined Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and was subsequently subjected to the attentions of RAF Bomber Command.

#

On 26 May, Swordfish torpedo-bombers from the Ark Royal and Coastal Command’s patrol bomber (PBY) aircraft regained contact with the Bismarck. Late in the day, Swordfish from the Ark Royal attacked, and a lucky torpedo hit jammed the German battleship’s twin rudder system, making her unable to maneuver. With no air cover or help from the U-boats or other ships available, the fatalistic Fleet Commander Admiral Lütjens, remembering the reaction to the scuttling of the Graf Spee and Raeder’s orders to fight to the last shell, radioed the hopelessness of the situation.

At 8:45 A.M. on 27 May, the British battleships King George V and Rodney opened fire. By 10:00, although hit by hundreds of shells, the Bismarck remained afloat. As the heavy cruiser Dorsetshire closed to fire torpedoes, the Germans scuttled their ship. Three torpedoes then struck, and the Bismarck went down. Reports of German submarines in the area halted British efforts to rescue German survivors. Only 110 of the crew of 2,300 survived. Lütjens was not among them.

Nicknames: Stringbag; Blackfish (Blackburn-built Swordfish)

Specifications (Swordfish Mk II):

Engine: One 750-hp Bristol Pegasus XXX 9-cylinder radial piston engine

Weight: Empty 4,700 lbs., Max Takeoff 7,510 lbs.

Wing Span: 45ft. 6in.

Length: 35ft. 8in.

Height: 12ft. 4in.

Performance:

Maximum Speed: 138 mph

Ceiling: 10,700 ft.

Range: 1,030 miles

Armament: Two 7.7-mm (0.303-inch) Vickers machine guns (one forward-firing and one one in a Fairey High-Speed Mounting in rear cockpit); plus one 1,600-pound torpedo, or 1,500 pounds of depth charges, bombs or mines; or up to eight rockets on underwing racks.

Number Built: 2,391