In was decided in May of 1944 that the experienced Maj. Robert Kowalewski’s KG 76 would be the first Luftwaffe unit to receive the jet-powered Ar 234 bomber now starting to come out of the Arado factory. The only operation of the 234 in the summer of 1944 was as a high-performance camera carrying reconnaissance aircraft. Flying as Kommando Sperling the Staffel-sized unit demonstrated the dramatic capabilities of the B-series aircraft in several spectacular reconnaissance missions over the Allied invaders in August and later in the fall. After months of complete inability to gather aerial reconnaissance Kommando Sperling gave the Luftwaffe ability to scout Allied rear positions freely at will. The plane was a tremendous success.

But the III/KG 76 under Hptm. Dieter Lukesch would be the first unit to be equipped with the revolutionary bomber. Lukesch first flew the plane in July; it was love at first sight. It was very fast, easy to control and with the bubble glass nose possessed excellent visibility. On August 26th the first two bombers were delivered to the unit. Conversion training from their Ju-88A4s beginning almost immediately near Magdeburg. All the pilots chosen had extensive experience and Lukesch found that training went smoothly, although some had trouble with horizontal stability since the pilot was so far forward that there were no engines or wings to look at to help keep one’s bearings.

Helmut Rast was one of the chosen pilots. Rast had been a 19-year old student at Munich Technical School when the war broke out and soon became a flight instructor. However, he was bored with student flying and in 1943 obtained a transfer to the Luftwaffe’s major proving center at Rechlin as a test pilot. There he tested the very latest products of German genius, many of which were extremely dangerous in the test phase. But his personal favorite was the new Arado 234B the “Blitz” then in preparation for its assignment to the Luftwaffe as a reconnaissance aircraft. Rast found the jet a thing of beauty. The bubble-nosed bird handled smoothly and was exceptionally fast. Rast’s reputation flying the 234 rose quickly, being enlisted to conduct a mock combat with a Fw-190A, at the time one of the leading German piston powered aircraft. Rast’s 234 easily outpaced the Focke Wulf in level flight and was faster in climb and descent. One performance limitation was the 234’s turning radius which was very wide relative to the piston-powered fighter. But the major weakness was acceleration; the throttles of the Junkers Jumo 004Bs could not be changed rapidly during takeoff and landings. Vulnerable to attack, the low speed on approach or takeoff could not be changed quickly enough to execute defensive maneuver. Regardless, Rast’s superiors were greatly impressed by his mock combat. He was promoted to Unterfeldwebel and was eagerly assigned to the post of the first combat unit to use the 234, III Gruppe of KG 76. At Burg the pilots trained in earnest with their new craft.

There were problems with the bird, however, which had not really completed flight testing. “Hardly any aircraft arrived without defects,” and Lukesch remembered they “were caused by hasty completion and shortage of skilled labor at the factories.” Training continued throughout the fall, hampered by the slowly accumulating number of aircraft and a variety of accidents associated with the new type.

Two methods of aiming the 3,000 lb bomb load were developed. The first was to drop the bombs during a shallow dive with special periscope sight and a trajectory calculator; the second involved putting the jet on automatic pilot at high altitude and then using the Lotke 7K bombsight to release the bombs automatically after the target was centered in the crosshairs. This advanced technique had considerable safety advantages since high-speed, high-altitude flight could be maintained where the Ar 234 was nearly invulnerable to slower Allied fighters. However, Lukesch felt the method impractical since the Allies quickly learned to attempt attacks on the speedy jets from above with the faster piston types particularly the Tempests, and having one’s hands on the control and able to see behind the aircraft was vital to survive such assaults. Installation of the technically advanced autopilot also slowed the delivery of the aircraft to the unit and it was the end of October before III/KG 76 had 44 Ar 234s available.

Training conversion continued in earnest for the fledgling jet unit in November, although plagued by accidents. Some problems, such as getting used to the tricycle landing gear, were due to differences with the Ju-88, but a variety of troubles arose from the machines themselves. One unexpected problem was that the two Jumo 004 engines were too powerful for their own good and an unladen Ar 234 could easily approach the speed of sound where Chuck Yeager’s demon lived. A good example is the experience of Uffz. Ludwig Rieffel who was hurt when he mysteriously lost control of his Ar 234 near Burg on November 19th:

“The effects of nearing the sound barrier were virtually unknown to us at this time, the high speed of the aircraft sometimes surprising its victims. Rieffel was practicing a gliding attack when he experienced a reversal of the controls at Mach 1. He bailed out successfully, but the shock of the parachute opening at that speed ripped three of its sections from top to bottom. A freshly plowed field prevented him from being seriously injured. This happened later to Oblt. Heinkebut he was unable to escape from the aircraft which crashed into the ground in a vertical dive”

At the end of November KG 76 was reaching its operational strength with 68 Ar 234s on hand. On December 1st, the famous bomber ace and veteran of some 620 operational sorties, Maj. Hans-Georg Bätcher, took command of III/KG 76 to take the jet bombers into action. With so many bomber units now disbanded, Bätcher had the pick of the German bomber pilots. Pilots with the unit included Hptm. Diether Lukesch, holder of the Ritterkreuz with Oak Leaves and veteran of some 372 missions, as well as Hptm. Josef Regler, a veteran with 279 operational sorties under his belt. Unlike the fighter pilots, where the attrition and demand for pilots often meant low skill levels, the pilots with the Gruppe all had extensive flying experience.

Regardless of the minor danger posed by these small groups of German planes, the Allies had a phobia about them and kept their bases at Achmer, Hesepe and Rheine under constant surveillance. Only the profusion of 20mm flak around the bases and a standing guard of German piston-powered planes allowed the jets to get off the ground or land without being shot down during the vulnerable portion of their flight. Still the German bases harboring the jets received much unwelcome attention. A carpet-bombing raid on the Rheine base on November 13th killed many members of KG 51.

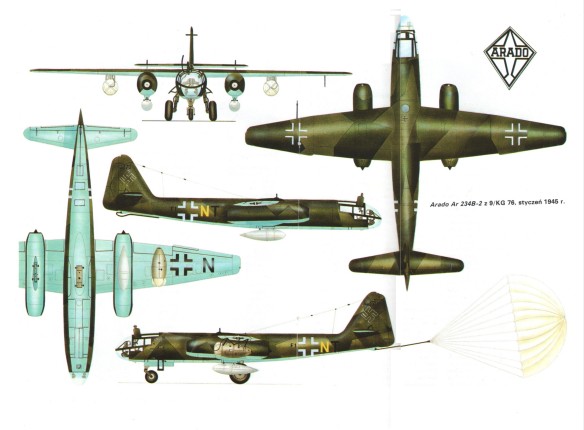

The Arado Ar 234 Blitz (Lightning) was the Luftwaffe’s second operational jet, the other being the Messerschmitt Me 262, and it was the first operational jet bomber and long-range, high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. Problems with engine development and landing gear configuration design, along with fuel and material shortages, delayed production until late in World War II, and too few became operational to change the war’s final outcome. Approximately 234 B and C variants were completed at Lönnewitz from December 1944 to early 1945.

DESIGN

Initial development began with Arado Flugzeugwerke engineers Walter Blume and Hans Rebeski submitting a technical proposal to the German Air Ministry. The proposal was accepted and a design team was established, led by T. Rüdiger Kosin. The aircraft was unlike any under development by the Allied Powers at the time and featured a slender fuselage, and high-wing design, with two Junkers Jumo 109-0004 turbojets housed in nacelles under the wings; these features gave it a maximum top speed of 456 miles per hour (735 kilometers per hour), outperforming any conventional radial or inline fighter. Another unusual design feature was the cockpit, which was located in the nose with a large glazed canopy affording the crew a wide viewing area. With a required combat range of some 1,300 miles (807 kilometers), the designers had to include internal tanks behind the cockpit.

The designers initially could not solve how to fit conventional landing gear due the Ar 234’s high-wing design. During takeoff, the early prototypes—Ar 234V-1 to V-5 (Ar 234A series)—employed a reusable tricycle trolley that was jettisoned upon becoming airborne, while landing skis fitted to the aft fuselage and wings were lowered for landing. The first prototype was completed and flight-tested in June 1943, followed by two more in September; the prototypes were initially ready by the end of 1941, but engine development and production became problematic, thus delaying testing and production by two years.

The Jumo 109-0004 powered both the Ar 234 and the Me 262; because the Me 262 took precedence, supplying the engines in adequate numbers was impossible. The powerplant also required a rebuild after only ten operational hours and was known for flameouts. Prototypes Ar 234V-6 to V-8 retained the carriage ski configuration but were powered by lower-thrust BMW 1009-003-A1 engines as an alternative to the -0004. Those three aircraft went into the development of the Ar 234C, in which fewer than half of the 14 produced were fitted with engines before the war ended.

A redesign requested by the Air Ministry consisted of enlarging the mid-fuselage, along with removal of a fuel tank to accommodate a tricycle landing gear, and installation of a recessed bomb bay in the fuselage and a periscopic optical sight above the cockpit for rearward viewing. The pilot-bombardier during a bomb run switched on the Patin PDS autopilot and then swung the control column away to use the Lotfe 7K bombsight. A maximum external and internal bomb load capacity of over 3,300 pounds (1,497 kilograms) reduced the maximum speed to 415 miles per hour (668 kilometers per hour). The three prototypes built in this fashion were designated Ar 234V-9 to V-11 (Ar 234B series) with the first test flight occurring in March 1944. Production units were designated Ar 234B.

Several of the trolley and ski prototypes and B-1 and B-2 airframes were modified as recon platforms, with the rear fuselage housing two to three vertical and oblique cameras: the Reihenbilder (Rb) 50/30, Rb 75/30, Rb 20/30 series. Two recon variants in development, consisting of the Ar 234C-1 and the two-man Ar 234D, were not completed.

Erich Sommer.

RECONNAISSANCE OPERATIONS

V-5 and V-7 prototypes, equipped with rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO) were sent to I./Versuchsverband Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe in July 1944 for operational evaluation. The first reconnaissance mission was conducted of the Allied landing areas in Normandy by Erich Summer, piloting the V-5 prototype on 2 August 1944. For this mission, two Rb50/30 cameras were mounted on the back of the fuselage, inclined at twelve degrees on either side of the aircraft, allowing photographs to be taken in a 10km band around the trajectory of the aircraft. On the same day, the plane was joined by the other prototype and between them they carried out other similar missions over the following three weeks. In September, the two planes were withdrawn from operations and replaced by the first Ar 234Bs. From October, this aircraft would perform its reconnaissance role, even flying over England in order to determine whether or not a new invasion was being prepared for the Netherland’s coast. It was only on 21 November that a training escort of P-51Bs saw the Luftwaffe’s jet aeroplane for the first time. Realising they’d been seen, the Arados were able to evade the Mustangs, thanks to their quicker speeds and ability to fly at greater altitude.

Special Unit Sonderkommando (SdKdo) Götz operated four Ar 234B-1s near Rheine in Westphalia, Germany, and ran reconnaissance missions over Allied-held territory and the British Isles beginning in October 1944. SdKdo Hecht and Sperling were activated in November 1944 but deactivated and replaced by I./Fernaufklärungsgruppe (FAGr) in January 1945. SdKdo Summer operated three Ar 234B1s at Udine in northern Italy, while I./FAGr 123, based in Germany and Norway, and I./FAGr 33 flew missions over Germany and Denmark.