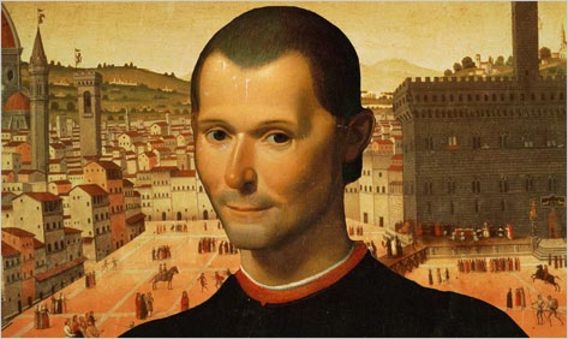

Niccolo di Bernardo dei Machiavelli

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), the Italian Renaissance figure whose name is still cited frequently today by scholars, politicians, and debaters alike, had negative views on mercenaries.

The son of a legal official, Machiavelli had a good grasp of Latin and the Italian classics when he entered government service in 1494 as a clerk. After the Florentine Republic was proclaimed four years later, he rose to prominence as secretary of the 10-man council which conducted Florence’s diplomatic negotiations and military operations. It was during his diplomatic missions that he became familiar with the political tactics of many Italian leaders. In 1502 and 1503, Machiavelli also became familiar, at first hand, with the state-building methods of Cesare Borgia, the Duke of Romagna, who was expanding his holdings in central Italy through a mixture of military prowess, audacity, prudence, self-reliance, firmness, and cruelty. His army was essentially a mercenary army, heavy with contingents of French and Spanish troops. When he faced a revolt by his own mercenaries in 1502, he crushed it brilliantly and ruthlessly. Machiavelli studied closely the methods Cesare employed to trick the rebellious mercenaries and then magnified his achievements in The Prince.

From 1503 to 1506 Machiavelli was put in charge of reorganizing the military defense of Florence. At that time, condottieri bands (i.e. mercenary armies) were common in Italy, but Machiavelli did not think they could ever be relied on to remain loyal to their employers. He therefore argued in favor of citizen armies which, being native to a given state and thus having a personal stake in its fortunes, were much more likely to be loyal. Machiavelli’s thinking here was largely inspired by the citizen armies of ancient Rome.

In 1512, as a result of the rivalry between Spain and France (see the previous section on the Italian Wars), the Medici family returned to power in Florence. The republic was dissolved and, as a key figure in the former anti-Medici government, Machiavelli was placed on the torture rack because he was suspected of conspiracy. After his release, he retired to his estate near Florence, where he wrote his most important books. He tried hard to win the favor of the Medicis but was unsuccessful in this effort and was never given another government position.

Machiavelli’s best-known book—The Prince (Il Principe)—was not printed until l532, five years after his death, although an earlier version was first circulated in 1513 under the Latin title of De Principatibus (About Principalities). The basic and most famous teaching of The Prince is that a leader, in order to survive, let alone to win glory, is fully justified in using immoral means to achieve these objectives. Here the focus is on the two chapters of The Prince that have the most to say about mercenaries. It is worth quoting them at some length to get the full impact of Machiavelli’s thought.

His Chapter XII (“How Many Kinds of Soldiery There Are, And Concerning Mercenaries”), for example makes these forceful points:

I say, therefore, that the arms with which a prince defends his state are either his own, or they are mercenaries, auxiliaries, or mixed.

Mercenaries and auxiliaries are useless and dangerous; and if one holds his state based on these arms, he will stand neither firm nor safe; for they are disunited, ambitious and without discipline, unfaithful, valiant before friends, cowardly before enemies; they have neither the fear of God nor fidelity to men, and [one’s own] destruction is deferred only so long as the attack is; for in peace one is robbed by them, and in war by the enemy. The fact is, that they have no other attraction or reason for keeping the field than a trifle of stipend, which is not sufficient to make them willing to die for you. They are ready enough to be your soldiers whilst you do not make war, but if war comes they take themselves off or run from the foe….

I wish to demonstrate further the infelicity of these arms [i.e., mercenaries]. The mercenary captains are either capable men or they are not; if they are, you cannot trust them, because they always aspire to their own greatness, either by oppressing you, who are their master, or others contrary to your intentions; but if the captain [i.e., the leader of the mercenaries] is not skillful, you are ruined in the usual way [i.e., you will lose the war].

And if it be urged [i.e., argued] that whoever is armed will act in the same way, whether mercenary or not, I reply that when arms have to be resorted to, either by a prince or a republic, the prince ought to do in person and perform the duty of captain…. And experience has shown princes and republics, single-handed, making the greatest progress, and mercenaries doing nothing but damage; and it is more difficult to bring a republic, armed with its own arms, under the sway of one of its citizens than it is to bring one armed with foreign arms. Rome and Sparta stood for many ages armed and free. The Switzers are completely armed and quite free.

In his Chapter XIII (“Concerning Auxiliaries, Mixed Soldiers, And One’s Own”), Machiavelli provides his considered findings on this subject:

And if the first disaster to the Roman Empire should be examined, it will be found to have commenced only with the enlisting of the Goths [as mercenaries]; because from that time the vigour of the Roman Empire began to decline, and all that valour which had raised it passed to others.

I conclude, therefore, that no principality is secure without having its own forces; on the contrary, it is entirely dependent on good fortune, not having the valour which in adversity would defend it. And it has always been the opinion and judgment of a wise man that nothing is so uncertain or unstable as fame or power which is not founded on its own strength. And one’s own forces are those which are composed either of subjects, citizens, or dependents; all others are mercenaries or auxiliaries.

In making these such statements, however, Machiavelli was certainly not a disinterested scholar. He very much wanted to get another high-level position with the government of Florence, and the only way to do so was to win the support of the ruling Medici family. A letter written by Machiavelli and discovered only in 1810 reveals that he wrote The Prince to impress the Medicis. However, since they were not prepared to pay the very high fees demanded by the best warriors of the time—namely, the Swiss mercenaries—in The Prince he had to fall back on a less-effective but more feasible solution, namely, a rural militia composed of Florentine citizens. Such a force, he argued, would be much cheaper and much more reliable than mercenaries.

Machiavelli clearly hoped that this proposal, coupled with his related ideas on the merits of a strong indigenous government (which was badly needed, in his view, to keep Florence free from foreign domination), would commend itself to the Medicis. It is clear, however, that it did not: Machiavelli never got another job, and mercenaries continued to be widely used by Italian city-states and by other employers.