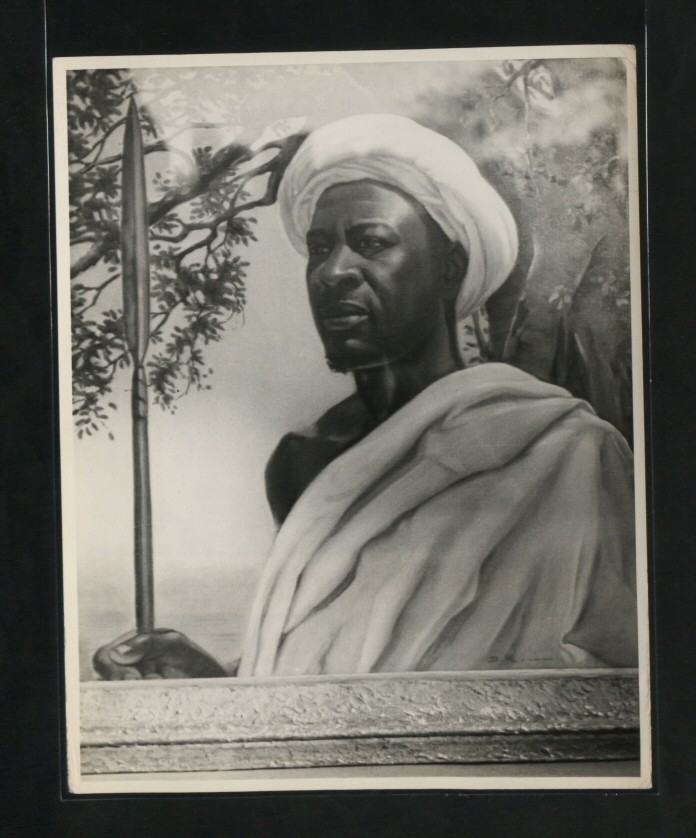

Chief Mkwawa

Map of Kalenga – Iringa in 1897 (showing the German attack)

Despite their success at Lugalo, and the raids which they were in the habit of launching against native enemies, Hehe strategy seems to have been essentially defensive. Oral tradition describes their immense confidence in the fort which Mkwawa had built at Kalenga, of which the people sang that ‘there is nothing which can come in here, unless perhaps there is something which drops from the heavens’ (Redmayne). It had originally been surrounded by a simple wooden stockade, but the king had sent an officer called Mtaki to the coast to study the Arab fortifications there, and – inspired by his report – had ordered it to be rebuilt in stone. Work began about 1887, and by 1894 the whole site – nicknamed ‘Lipuli’, or ‘Great Elephant’ – was surrounded by a stone wall about 2 miles long, 8 feet in height and up to 4 feet thick. The garrison was 3,000 strong and included the two Maxim guns captured at the Lugalo. However, the Hehe did not know how to operate these, so they played no part in the siege and were eventually recaptured intact by the Germans.

With hindsight Mkwawa’s confidence in this fort seems incomprehensible. The impressive perimeter was too long for the garrison to hold in strength, and there was no operational artillery to counter the German field guns, which had already destroyed stone forts at Isike and elsewhere in East Africa. Mkwawa must have been aware of this, because his garrison had been joined by a group of anti-German Nyamwezi who had survived the fall of Isike. Tom Prince, who fought in the siege, believed that if they had made a stand outside the fort the Hehe would probably have won another victory, but their ruler would not allow this. To make matters worse, Mkwawa still had his arsenal of 300 rifles under his personal control, and had only issued 100 of them when the attack came. According to Hehe tradition he had temporarily lost his wits, ordering his warriors to load their guns with blank charges, and placing his reliance on magic charms placed on the paths to deter the German advance.

So when the long-awaited German invasion force came, it encountered no resistance as it approached Kalenga and built a stockaded camp only 400 yards from the walls. The column was commanded by the provincial governor, Freiherr von Schele, and comprised three companies of askaris and a number of field guns. For two days the artillery battered the defences, then on 30 October a storming party under Tom Prince scaled the walls and broke into the fort. The walls themselves proved to be only lightly held, while the main body of the defenders was hidden among the huts inside, those with firearms shooting from concealed positions on roofs and in doorways. According to von Schele’s report (Schmidt), every house inside the stronghold had been specially prepared for defence, complete with loopholes and reinforced walls. But after four hours of fighting Mkwawa realized that the fort was lost: he allegedly tried to blow himself up inside one of the houses, but was led away to safety by his officers. At this point resistance collapsed and the Germans took possession of Kalenga with its stores of gunpowder and ivory. One German officer and eight askaris had been killed, with three Germans and twenty-nine askaris wounded. Von Schele claimed that 150 Hehe died in the fighting or were burnt to death when the attackers set fire to their huts. If correct this figure would represent only 5 per cent of the garrison, which does not imply a particularly determined defence: perhaps the Hehe were demoralized by the ease with which Prince’s men had surmounted the supposedly impregnable wall, or possibly Mkwawa’s departure had persuaded them that further resistance was useless.

But Hehe morale was quickly restored, and resistance continued in the hills outside the fort. On 6 November a force estimated at 1,500 warriors charged von Schele’s marching column on its return journey to Kilosa. They broke through the line of porters, but were stopped by the rifle fire of the askaris and retreated, leaving twenty-five dead behind. Once again the authorities tried to open talks with Mkwawa, but he wisely refused, no doubt aware of the German habit of arresting their enemies during negotiations. He continued to avoid attacking regular troops, while raiding the neighbouring tribes who had submitted. So in 1896 Prince was sent with two companies of askaris, each 150 strong, to establish a fortified post at Iringa, a few miles from the ruins of Kalenga. In an attempt to divide the Hehe, Prince recruited Mpangile, the victor of the Lugalo battle, who had recently surrendered to the Germans. He was given the title of ‘sultan’, and set up as a puppet ruler over the pacified Hehe villages. Mpangile gained nothing from his defection, however. In February 1897 Prince became suspicious that he was secretly ordering attacks on German patrols, and despite a lack of concrete evidence summarily executed him.

The war dragged on for two more years, but there were no more major engagements. The Hehe resorted to guerrilla warfare, ambushing isolated patrols and caravans and raiding the villages which were under German control. Prince sent his askaris out on regular patrols to hunt down hostile bands and burn the villages which sheltered them. On several occasions they came near to capturing Mkwawa, and gradually their scorched earth tactics bore fruit. Drought and famine intensified the pressure, and in the first half of 1897 more than 2,000 warriors came in and surrendered. Now only a hard core of loyalists remained around Mkwawa. In January 1898 one of Prince’s columns surprised the Hehe chief’s camp. Once again he got away thanks to a rearguard action by his followers, but many other warriors – described by Prince as ‘mere skeletons’ – were taken prisoner. Soon afterwards Mkwawa organized his last successful operation: an attack on a German outpost at Mtande, which took the thirteen-man garrison by surprise and annihilated it. The governor of German East Africa, General von Liebert, now offered a reward of 5,000 rupees for his head.

In July a patrol under a Feldwebel Merkl was following up information received from a local tribesman when it intercepted Mkwawa’s trail near the River Ruaha. The patrol followed it for four days, and eventually captured a boy who claimed to be Mkwawa’s servant and offered to lead them to where he was hiding. Near the village of Humbwe, Merkl was shown two figures lying on the ground, apparently asleep. It is an indication of how wary the Germans still were of their opponents that the Feldwebel made no attempt to take the men alive. Instead, obviously fearing a trap, he opened fire from cover. One of Merkl’s bullets struck Mkwawa in the head, but it was clear from the subsequent examination that both of the Hehe had already been dead for some time. Tired and ill, the king had first shot his companion and then himself. With his death all Hehe resistance ceased, but his surviving people continued to revere him, and in 1904 the Germans sent his sons into exile on the grounds that they were the focus of a potentially inflammatory cult honouring their father.

There was a further bizarre postscript to Mkwawa’s career. When the British took over Tanganyika in November 1918 at the end of the First World War, they received a request from the Hehe elders for the return of their king’s skull, which they said had been taken as a trophy by the Germans twenty years earlier. The German authorities continued to deny all knowledge of it, but the British governor of Tanganyika, Sir Edward Twining, continued to pursue the matter. He finally located the relic in 1953, in a museum in Bremen. It was formally identified by a German forensic surgeon from the bullet wounds, and in 1954 it was returned to Mkwawa’s grandson Chief Adam Sapi. It remains in the custody of the Hehe, as a memorial to their country’s finest hour.

Sources

Cameron, Thomson and Elton all have eyewitness accounts of the Hehe during Munyigumba’s reign. Redmayne’s article, based largely on anthropological fieldwork among the Hehe, provides a comprehensive overview of the history and organization of the kingdom. The main source for the war from the German side is Schmidt.