La Doutelle & L’ Elisabeth meet HMS Lion: July 9th 1745

THE FORTY-FIVE

In the spring and summer of 1745, Britain faced a growing crisis in Flanders. On 11 May, Saxe defeated Cumberland in the long, bloody duel of Fontenoy. Ghent and Bruges were lost in July, and Ostend capitulated on 23 August. This was very bad indeed and distracted British attention away from the plans of Charles Edward who appeared to be a very small player in the midst of such grand manoeuvres. However, on 22 June, the prince boarded the frigate Le du Teillay and sailed from St Nazaire. He was about to take centre stage. Nearly three weeks before his departure, the prince had written to Louis XV, whom he addressed as ‘uncle’ intimating that he had resolved single-handedly to make himself known by his deeds. To embark on an enterprise to which even a very moderate amount of help would ensure success, and being so bold as to think that the King of France would not refuse this:

I would certainly not have come to France if the expedition which was planned to take place last year [1744] had not shewn me that your Majesty wished me well . . . and so I go to seek my destiny which, apart from being in the hands of God, is in those of your Majesty.

This would clearly seem to indicate Charles had confidence in the eventual certainty of French aid, once his expedition should be seen to stimulate results. What he had not taken into account was the fact that Fontenoy and the gains in Flanders had conferred the strategic initiative on France. There was no real need for any sideshow, other than it might sow further confusion. Certainly, the French could not pretend they were unaware of what was afoot. One of the vessels the Prince’s entrepreneurial friends had chartered was the 64-gun L’Elisabeth. It was quite customary for the French Navy to grant charters with letters of marque to enterprising merchant raiders, who might seek a profit from the wars. It appears unlikely that L’Elisabeth could have been hired for the expedition to Scotland without the direct authority of the minister concerned.

The ship carried a naval complement, and large stores of arms, accoutrement, powder and shot had been amassed, which required ministerial authorisation. From the French perspective, the expedition was a low cost extension to the war which had the potential to increase the pressure on Britain, with whom France was tentatively seeking to negotiate. Charles had, on 12 June, written to his father to explain the desperate venture on which, without James’s commission, he was about to embark:

I believe your Majesty little expected a courier at this time, and much less from me; to tell you a thing that will be a great surprise to you. I have been, above six months ago, invited by our friends to go to Scotland, and to carry what money and arms I could conveniently get; this being, they are fully persuaded, the only way of restoring you to the Crown, and them to their liberties . . . After such scandalous usage as I have received from the French Court, had I not given my word to do so, or got so many encouragements from time to time as I have had, I should have been obliged, in honour and for my own reputation, to have flung myself into the arms of my friends, and die with them, rather than live longer in such a miserable way here, or be obliged to return to Rome, which would be just giving up all hopes . . . Your Majesty cannot disapprove a son’s following the example of his father. You yourself did the like in the year ’15; but the circumstances now are indeed very different, by being much more encouraging, there being a certainty of succeeding with the least help. . . . I have tried all possible means and stratagems to get access to the King of France, or his Minister, without the least effect . . . Now I have been obliged to steal off, without letting the King of France so much as suspect it for which I make a proper excuse in my letter to him; by saying it was a great mortification to me never to have been able to speak and open my heart to him. Let what will happen, the stroke is struck, and I have taken a firm resolution to conquer or to die . . .

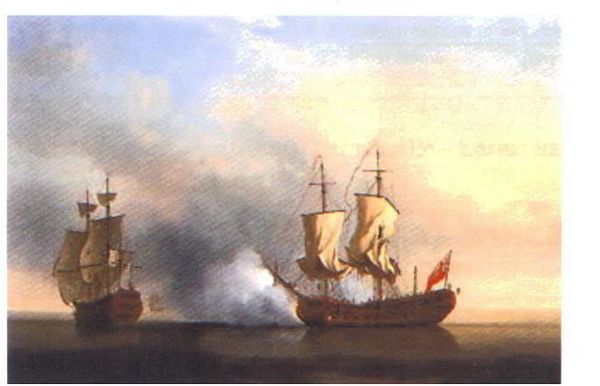

Brave words, appropriate in the romantic, if not the pragmatic, sense, Charles, in this apologia to his father, suggests he has been drawn to the Scottish venture by the assurance and entreaty of sympathisers there, but his initial reception in the Highlands would indicate otherwise. On the other hand, the expedition may be seen to represent the final throw of the despairing gambler, determined to risk all on a last roll of the dice. The fact that the fount of overt French support had dried up should have indicated to a wiser man how the land lay in that direction. Hubris is a poor reason for campaigning without some more substantive bedfellows. On 2 July, the sleek du Teillay was joined by the heavier and ageing L’Elisabeth off Belle Isle, and the pair sailed north-west until, with typical misfortune, they ran foul of HMS Lyon (58 guns). The English man-o’-war, if under-gunned, was faster, having just been refitted. Captain Dan of L’Elisabeth ran out his guns to make a fight of it. The French ship cleared for action, exchanged token shot and hoisted her colours. The Englishman gave chase and presently the two warships were exchanging broadsides. No subtlety here, but a grinding, yardarm to yardarm, attrition of screaming round shot.

At one point in the action, Lyon was able to rake her opponent, causing fearful loss, yet she certainly did not have matters all her own way, and the Frenchman shot away her rigging and partly dismasted her. The battle raged until darkness when L’Elisabeth limped back towards Brest with 57 dead, including her gallant skipper, and nearly twice as many wounded. Though she was neither sunk nor taken, her priceless cargo of supplies and quota of volunteers was lost to Charles Edward. Diminutive du Teillay, with the prince’s equally modest entourage on board, sailed on alone. Despite the continued vigilance of the Royal Navy, Captain Durbe steered his ship north and west, around the treacherous coast, past the bastion of Cape Wrath and, on 23 July, sighted the Outer Hebrides. The vessel made landfall off Barra, where the steep hills crowd down to the anchorage. The Highlander turned financier, Aeneas MacDonald, went ashore to establish contact with his brother-in-law and staunch Jacobite, Macneil of Barra: The Forty-Five had begun.

It did not begin particularly well for the prince. Macneil was away and it was feared the government had rumbled the whole affair. Undeterred, Charles was for pressing on. There was a further fright when what appeared to be a large man-o’-war was sighted and du Teillay took shelter among the necklace of islands. More alarums followed. Charles and his tiny band received a taste of the fury of a West Coast summer storm. The laird of Boisdale was the first man of consequence the prince spoke to on the barren strand of Eriskay. His advice was as harsh as the wind, but the Jacobite counsels were disturbed by the renewed attentions of supposed British warships.

On 25 July the swift French frigate nosed into Loch nan Uamh and the prince, with his tiny entourage, stepped ashore at Arisaig.8 Charles was now upon his native land, the arms and stores were unloaded and local gentlemen consulted. Having revictualled, du Teillay made ready to put out to sea. If Prince Charles Edward was having any second thoughts, now was definitely the time. If he lacked wisdom and judgement, he lacked for neither courage nor energy. Durbe and Walsh, who had accompanied the voyage, said their farewells, the latter departing with a letter of commendation from the prince in his pocket. It was time for business.

Whether the prince possessed sufficient intellectual wherewithal to contemplate the wider, European picture, must remain doubtful. That he first allowed himself to be deceived before proceeding, in turn, to deceive others may be quite likely. The Forty-Five, therefore, was born out of false optimism and launched on pious hopes, presented as sure. In short, it was founded on an entirely false premise that the Highlands had but to show the white cockade and the French would be sufficiently enthused to intervene, as had been so tantalisingly close the previous year. None of those chiefs, seduced by the prince’s easy charm and charisma, which would hold only as long as he was seen to be winning, seriously envisaged that the clans must bear the weight of the whole campaign unaided.

Monday 19 August saw the prince with his following at Glenfinnan, where the high hills crowd the loch. Apart from a pair of local shepherds, the tranquillity was undisturbed by the tramp of marching feet. After what must have been an increasingly anxious wait, a small MacDonald contingent, no more than 150 broadswords, came in and, with them, James Mor MacGregor, son of the celebrated Rob Roy and as much a rogue. It was not until around four in the afternoon that Cameron of Lochiel finally made an appearance, bringing in perhaps 700 of his affinity, to be followed by Keppoch with, at best, half as many. It was scarcely an army, hardly sufficient for two weak battalions.

What followed was a formidable feat of arms. Charles’s ragged forces defeated Cope at Prestonpans. Despite the chiefs’ misgivings, the army was soon tramping in good order down the western spine of England. They took, firstly Carlisle, then, on 27 November, Preston. Despite a remarkable dearth of recruits, the clan regiments pressed on initially to Manchester and, finally, on 4 December attained Derby. Whether the decision forced upon Charles by his officers to withdraw was the correct one remains open to debate.10 But the prince, his brittle personality bruised by this reverse, took more and more counsel with his Irish cronies, and a widening chasm opened with his Highland commanders, particularly Lord George Murray. If Charles had significantly misrepresented the actual level of likely French support, his core belief that victories won by the Highland army might stimulate their enthusiasm to the point of significant military intervention was not so wide of the mark. Even as the rebel army was setting its face towards north and beginning a long retreat from the high-water mark of Derby, some modest French reinforcements succeeded in eluding the Royal Navy blockade and entering Montrose.

This was not an army; the Royal Ecossais was merely a weak composite battalion of companies drawn from the regiments in the Irish Brigade. Nonetheless, as far back as 13 October, Louis had taken a decision to support Charles with a force of several thousands. By mid November, the ubiquitous Walsh was instructed to assemble transports and the Irish were moved up to Dunkirk. Any chances of the expedition setting sail were hampered by adverse winds, while the RN waited in the Downs. A landing either on the south coast or further west seemed the likeliest option. So heightened was the tension in England that on 10 December a French descent was announced – somewhat prematurely – the supposed invaders were nothing more than local smugglers plying their illicit trade off Beachy Head! As ever, the RN took the fight to the enemy, the French shipping constantly subjected to enterprising cutting-out raids, which relieved the French of a score and more of vessels.

On land, the Duke of Cumberland and his officers were determined that this affair, which had seemed to shake the very roots of his family’s dynasty, should not peter out with the clans melting back, unscathed, into the heather. It was time for a final and decisive reckoning. On 17 January, a further battle was fought at Falkirk, a confused and untidy fight in which the government forces, led by General ‘Hangman’ Hawley, were again worsted. Almost three months later, on 16 April, the last great battle to be fought on British soil erupted at Culloden. The Jacobites, depleted, hungry, exhausted and footsore, confronted the larger Hanoverian army, well-formed, well-drilled and competently led. In the driving sleet, the clans charged for the last time, winnowed by round shot, grape and musketry. They fell by companies, by midafternoon it was all over, and the Stuart cause was in ruins. Charles, who had commanded in person, fled the field, and his corpulent cousin, Cumberland, enjoyed the only victory of an otherwise failed military career.

A few weeks before the battle, a French sloop, aptly named The Prince Charles, formerly HMS Hazard, which the Jacobites had taken in Montrose harbour less than six months before, had attempted to land additional detachments from the Irish Picquets. These reinforcements would have been welcome. Even more welcome would have been the quantity of gold coin on board; that the prince’s war chest was empty may have been a spur to his accepting battle on Culloden Moor. Captain Talbot, who had attempted to run the blockade and make landfall at Portsoy on the Moray Firth, came up against a quartet of British men-of-war: the 40-gun Eltham, Sheerness (24 guns) and the fast sloops Hawk and Hound. The odds were unfortunate, and Talbot crowded sail to run northwards along the coast. Pursuit was relentless and, as a fitful wind dropped, the fine sailing qualities of Le Prince Charles were of little advantage. Only by taking to the oars and rowing for their lives did the ship’s company escape into the darkness. By dawn, she was off Caithness preparing to run the Pentland Firth, when her pursuer once again hove into view. This was a classic sea chase of the age of sail. The sloop had to try and outrun her tormentor. If the frigate closed, the ship was lost, for Le Prince Charles was heavily outgunned. Worse, Talbot’s Jacobite pilots were all Islesmen, unfamiliar with these waters. As she now fled westwards, the Frenchman was moving ever further away from the HQ of Charles’s cash-strapped army at Inverness.

Talbot encountered a small fishing smack and took the crew as unwitting and unwilling guides. Knowing he could probably not now outrun the frigate, he sought any haven where his shallow draft would confound the pursuit. As the tide ebbed, the French captain ran his small vessel into the shallows of the sands of Melness at the western opening of the Kyle of Tongue. O’Brien of Sheerness took the risk of fouling as he swept in behind. A standoff now ensued, both ships riding at anchor, guns run out. Talbot could not match his adversary’s broadside, six-pounders against nines, but he was game and full of fight, his crew perhaps less so. For three hours battle raged, the smaller ship maintaining a gallant but ultimately one-sided fight. Sheerness’s gunners dismounted her deck guns and riddled Le Prince Charles’s masts and rigging; the decks a mess of tumbled yards and cordage, garnished with blood and entrails. With Le Prince Charles crippled, O’Brien stood off to finish the job at longer range. Talbot’s surviving crew had by now had quite enough and bolted for temporary sanctuary in the hold. Undismayed, Talbot drew his sword to beat them back to their posts, using the Picquets as marines. Despite such near-fanatical gallantry, there was no remedy for the fact his ship was badly holed and sinking. Cutting the cables, he allowed her to drift inshore and come aground.

Lugging their sacks of coin, the Irish soldiers, led by Captain Brown of Lally’s regiment, climbed down from the shattered hulk, disembarking all of their arms and powder, while still under intense fire. Talbot, remarkably unscathed, spat defiance at Sheerness and literally nailed his colours to the stump of the mast. The Frenchman’s wounded had to be left on the shot-scoured deck, while the fit survivors followed the Irish on to the beach. O’Brien had sent a commanded party of marines to cut off the landward exits. To escape they had now to move inland, over rough terrain, of which they knew nothing. A providential encounter with one of the few Jacobites in the vicinity, William Mackay of Melness, was encouraging, but his news was not. These French and Irish were in a hostile land. Lord Reay was a Whig and had raised two companies of militia to fight for King George. Mackay provided horses to carry the gold and his son as a guide. He could do no more. O’Brien had by dawn inspected the damaged vessel to see if she could be salvaged.

Lord Reay’s people too were not inactive. A forlorn hope of seven locals, led by his factor Daniel Forbes, were stalking the French column while the militia was mustering. Talbot had his own survivors from Le Prince Charles, many of the wounded left on board had succumbed during the night, six officers and three score other ranks from Berwick’s with a motley of volunteers from Clare’s, Royal Ecossais, the French Guards and some from Spanish service. Forbes, undeterred by the odds, kept up a steady harassing fire in the course of which his marksmen dropped eleven Irish, three of them fatalities. The fight spilled along the Jacobites’ intended line of march towards a high pass skirting the flank of Ben Loyal. Here 50 militia arrived to bolster Forbes seven. More potent than their numbers were their drums, a great rolling, dolorous tumult reverberated around the cockpit of the pass. The Jacobites, now cornered in the narrow arena, decided enough was enough and prepared to lay down their arms, first dumping their coin into Loch Hacoin. Factor Forbes, or so the story goes, salvaged 1,000 guineas as compensation for his efforts; not a bad morning’s work. As for the Jacobites, a vital resource was denied them. The Royal Navy, despite a most spirited and gallant opponent, had once again performed its role.

Final cannonades and the death rattle of the execution squads were not the final echoes of the Forty-Five. On 30 April 1746, two French privateers, Mars and Bellone had anchored in Loch nan Uamh, where it had all begun the previous year. The Frenchmen were initially sniped at by Jacobites onshore who believed them to be Royal Navy. These Highlanders, including Perth, Lord John Drummond and Lord Elcho, quickly acquainted their newly arrived allies with tidings of the disaster. The visitors were able to provide much needed supplies and took time to come ashore and marvel at the desperate poverty and general wretchedness of their hosts.

Captain Noel RN, on board the sloop Greyhound, was stationed barely 30 miles from Loch nan Uamh and was aware of the privateers’ presence. The rest of the captain’s small flotilla was widely dispersed but, by dawn on 2 May, both Greyhound and another sloop, Baltimore, were under sail and were later joined by a third, Terror. At first light, a little after three in the morning, these three small British vessels crept into the still waters of the loch.

John Daniel, a Jacobite volunteer, was, that night, sleeping among the other fugitives on the shore, and the sight of the British men-o’-war provided a most unwelcome jolt. The French, however, alerted by the sighting of an earlier patrol boat, were ready to fight. Captain Rouillee of Mars remained, unwisely, at anchor while Lory of Bellone got underway. To receive Greyhound’s broadside while thus immured was very nearly fatal, and Mars took a substantial pounding. Nearly a score of the privateers were killed, her decks, according to an eyewitness, awash with blood. One of the Jacobite refugees, Major Hales, was among the dead: having been bidden to throw himself to the deck to avoid injury, he preferred the upright pose of quixotic contempt, which, in his case, proved lethal. Baltimore now bore down on Mars, while Greyhound attacked Bellone. The two smaller British vessels were heavily outgunned and began, in turn, to suffer some serious punishment. Both suffered damage to their rigging, and Lory was manoeuvring to board. He failed, but the respite enabled Rouillee to slice cables and get his battered ship underway. The tiny Terror weighed into the fray, but was seen off by a broadside from Bellone. The two Frenchmen were now under sail, heading up the narrow confines of the loch with Mars taking shelter in a small bay, the three English ships, like terriers, snapping at Bellone.

For a good three hours the Jacobites on the shore were treated to the spectacle of a fierce little battle raging on the normally placid waters. It seemed as though Mars was crippled and could be picked off at leisure while the sloops directed their attention towards Bellone. Noel was not blind to the scurrying Highlanders on the shore, busily removing inland cargoes of arms and cash, the latter amounting to some £35,000 in bullion. Such a sum would have very possibly enabled the prince to stave off the defeat at Culloden and guaranteed the continuance of rebellion. Flying round shot from Greyhound added urgency to the work. Having managed to jury-rig repairs to his damaged sails, Captain Howe of Baltimore once more brought his vessel to the attack. Both his sloop and the gallant little Terror suffered grievously, Baltimore’s rigging and sails cut up, Howe himself among the wounded. After some six hours of battle, the fight petered out. All of the English ships had suffered damage, if relatively few casualties. Bellone unleashed a final broadside to speed the retreating ships on their way. Mars was by now in a bad state, hit repeatedly below the waterline, and with 29 dead and 85 wounded littering the decks, slippery with their spilled blood.

The French, knowing that other British ships could soon be expected to enable Noel to renew the assault, worked feverishly to ensure their badly holed vessel was seaworthy. Jacobites onshore meanwhile enjoyed the plentiful liquor their guests had left them. MacDonald of Barisdale, whose regiment had missed the fight, had by now appeared and began by appropriating a portion of cash before departing. The remaining Macleans too, dispersed, while one of the inebriated rebels unwisely elected to smoke his pipe in close proximity to a barrel of powder and succeeded in blowing himself to bits, his befuddled comrades mistaking the noise for a fresh alarum! As the privateers nursed battered ships back towards their Breton lairs, they took off the fugitive Duke of Perth, his brother and Lord Elcho.

John Fergusson was skipper of Furnace and, in April, before Culloden, his marines had engaged in a drink-fuelled foray against hapless MacDonald womenfolk on the island of Canna. Having finished with Canna, Fergusson moved his attentions to Eigg, where the business of rounding up rebels was leavened with additional pillage and rape. Captain Felix O’Neill, of Lally’s regiment, in the French service, was one of his victims, captured and about to be tortured until an officer of the Royals intervened and faced the brutal captain down. In their hunt for the prince, the soldiers and sailors of the crown even descended in force upon St Kilda, the most remote and westerly of the isles, whose terrified inhabitants must have seen these swarming redcoats as a vision of Hell. Needless to say, the prince was not to be found.

It would have been far better for Prince Charles Edward Stuart had he died on the field at Culloden, so history might remember a handsome, if flawed, young man, whose army came within an ace of unseating the House of Hanover. Better by far than the long years of an embittered, wasted life, his cause in ruins, increasingly an unwelcome anachronism, whose only succour came from a bottle; he died, also forgotten, in Rome in 1788.