On November 8, 1942, the United States, working closely with Britain through the Combined Chiefs of Staff, launched Operation Torch, aimed at creating bases in French North Africa from which to defeat Axis military forces then operating in the vicinity of the Libyan-Egyptian theater. Operation Torch represented the first major American military undertaking in the African–Middle Eastern region, since U.S. Marines and the U.S. Navy battled the Barbary pirates early in the nineteenth century. The operation, while a joint Anglo-American enterprise, marked the first major U.S.-led offensive operation against the Axis powers during the Second World War.

While the planning involving the entry of U.S. ground forces against the Axis powers had been ongoing, the timing of the actual amphibious operations landing a combined Anglo-American force into French North Africa was propitious. The German armed forces had just suffered two of their greatest setbacks at the battles of Stalingrad and El Alamein, and Hitler and the OKW then received news that the United States had transported its first army divisions into North Africa. The German high command knew this development would probably be followed by U.S. forces, combining with Allied troops in moving north across the Mediterranean Sea into Southern Europe.

Stalin, dictator of the Soviet Union, early in the war, had been pressing for the United States to open a second front against Germany by landing in Western Europe to alleviate the enormous pressure Berlin had brought to bear on the Soviet army, which was then defending on the Russian front. American commanders were keen to enter the fight, but their counterparts in Britain were more cautious and eventually “slow walked” the rising enthusiasm and clarion calls for U.S. troops to make a direct approach into the Nazi-defended Atlantic Wall. This view argued that American troops would be largely untested with limited training, as they moved to confront Germany’s battle-hardened Wehrmacht, and should they fail while suffering enormous casualties during the initial campaign, the downside for morale and the continued commitment by an already leery U.S. public would be substantial.

As the British high command had watched firsthand as Germany exploited in France and North Africa the speed, maneuver, and indirect approaches into its blitzkrieg doctrine, the question was fairly straightforward: Why attempt a direct approach into the ensconced strength of a waiting and ready opponent? The more viable strategy, it was argued, would be to adopt an indirect approach, bypassing the strength of the Atlantic Wall (the solid) and finding the “gap” that Churchill viewed as being the southern approach to the continent, which he referred to as the “soft under-belly of Europe.” U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt came squarely down on the side that argued for an indirect approach, providing U.S. soldiers and their field commanders more time to acclimate to the realities of a ground war with Nazi Germany.

The development of landing-craft

During the period between the wars, a few men in France and Great Britain still interested themselves in the problems posed by landing powerful forces away from a large port. To this end they envisaged the construction of motorised landing-craft fitted with drop-gates in the bows over which to land their troops.

In France, three vessels of this type had been built by May 10, 1940. On May 14 the Royal Navy’s landing craft put General Beihouart’s legionnaires and tanks ashore near Narvik, and a little later 11 of these vessels had taken part in the evacuation of Dunkirk. The experience gained from these small-scale operations was encouraging enough to prompt the British Admiralty to order 178 of these craft from English shipyards and another 136 from American sources. For since the Americans foresaw a war in the Pacific, their Navy too had been concerned with the problem of making effective large-scale landings in strength.

On the day of “Overlord”, taking together all the military theatres through- out the world, there were about 9,500 craft of all sizes and types under the British and American flags.

As these figures indicate, the Anglo- Saxon powers had committed themselves to an amphibious form of warfare needing enormous industrial and economic efforts which for a long time to come left their mark in one way or another on the general development of war-time operations.

American strategy

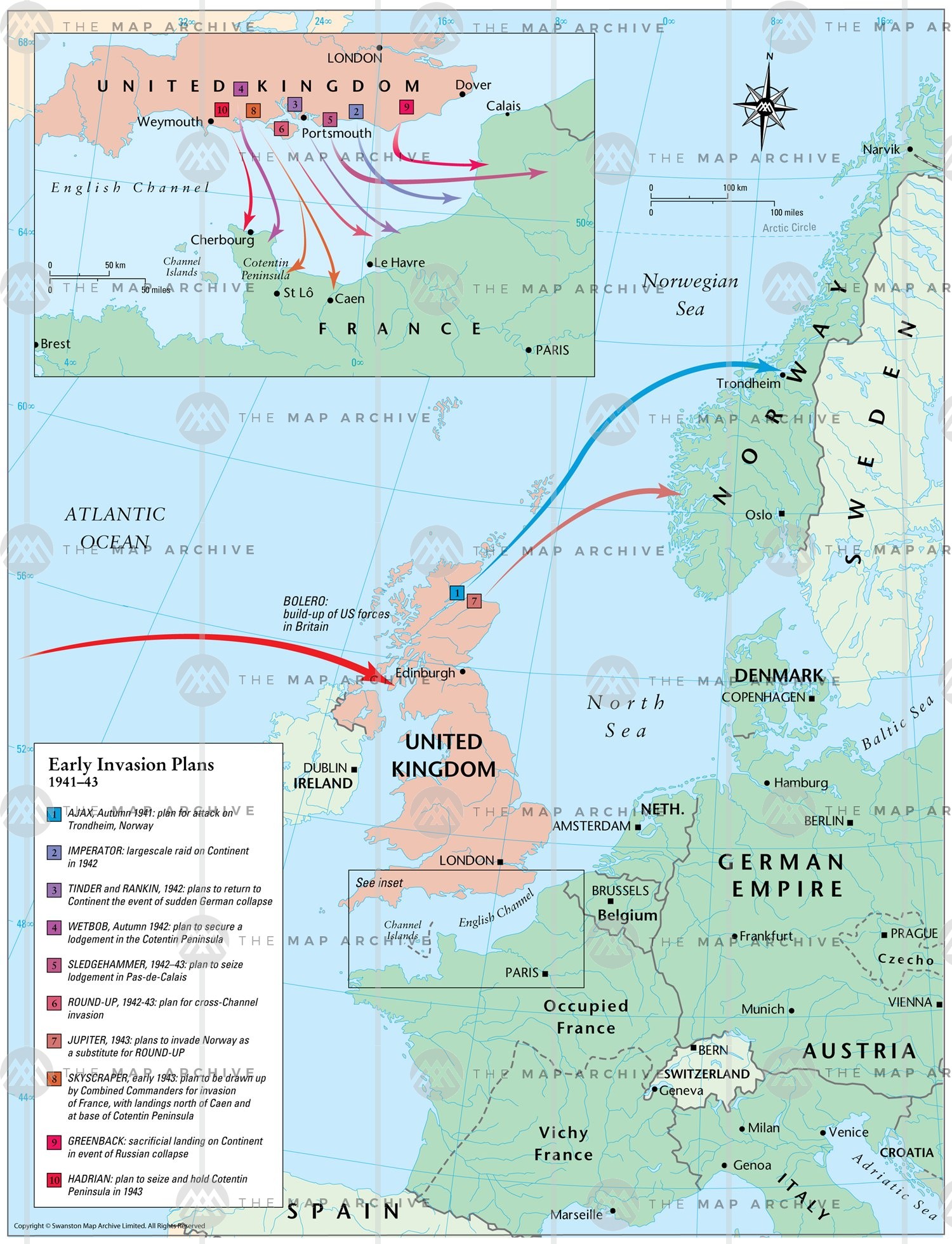

That this was so gradually became obvious later on, but neither Major- General Dwight D. Eisenhower, recently appointed to strategic planning, nor General Marshall were aware of it when, on April 1, 1942, they presented a plan of war to President Roosevelt. These comprised three separate operations:

1. Operation “Bolero” was to be initiated immediately, ensuring that within the period of a year 30 American divisions, of which six were to be armoured, should be moved across the Atlantic. These troops were to be complemented with air power whose task it would be to offer effective tactical support as well as to play its part in the R.A.F.’s strategic offensive against the industrial base of the Third Reich.

2. Once this logistic operation was completed, a major invasion of Western Europe would be launched in spring 1943. This operation was known as “Round-up”. It would involve 30 American and 18 British divisions, of which three were to be armoured. A vanguard of six divisions, reinforced by parachute regiments, would land between Le Havre and Boulogne. Strengthened at the rate of 100,000 men a week, this Anglo-American offensive would have as its primary objective the capture of the line Deauville Paris – Soissons – St. Quentin – Arras – Calais. Later on the line would be extended in the direction of Angers.

3. However, if the German army became suddenly greatly weakened by Russian victories, then the Western Allies should be ready to seize a limited bridgehead in the Cherbourg peninsula by September 1942. This scheme was called “Sledgehammer”.

Operations Sledgehammer, Roundhammer, and Roundup

At the conference in London on July 18-22, 1942, the conflicting perspectives of the British and Americans had to be reconciled. Since the British made it absolutely clear that they were not about to go forward with operation “Sledgehammer,” as the Northwestern Europe project for 1942 was code-named, the Americans had no alternative but to agree to dropping it. Obviously they could not insist on an operation which the British would have to mount and that the latter were certain would lead to a disaster which, after their earlier defeats, they simply could not contemplate. Given the situation at the time, this was very likely a correct assessment of the situation. The question then was what to do next. The Norwegian alternative was clearly out as well, having been earlier rejected in internal British discussions, and not appealing to American military leaders either. Some of the Americans, as already mentioned, wanted to transfer resources to the Pacific. Others did not wish to do this, and on this issue the decision of the American Commander-in- Chief, President Roosevelt, was unmistakably clear.

There had to be action in the war against Germany in 1942 in the President’s judgement. If the psychic as well as the material energies of the American people were to be engaged in the European war-as the Japanese on their own had arranged for them to be engaged in the Far East-then it was essential that there be a major operation against the European Axis as early as possible. Waiting for that until 1943 was unacceptable. As for concentrating on the Pacific, that made no long- term sense. A victory in the Pacific lay years off and would hardly affect Germany, while a victory in Europe would have immediate and dramatic repercussions on the war in East Asia. It was, therefore, essential that a major operation be launched in the European theater in 1942, and the obvious possibility was a revival of the project to invade French Northwest Africa, operation “Gymnast,” discussed earlier that year and now all the more desirable both because of the great danger in Northeast Africa and the potential contribution to easing the terrible shortage of shipping by clearing North Africa of the Axis. The great dilemma was that either nothing could be done at all in 1942 or “Torch” (the new name for “Gymnast”) could be launched at the risk of postponing any invasion of Northwest Europe, now referred to as “Roundup,” to 1944. The decision agreed upon was a landing in Northwest Africa later in 1942, to be accompanied by a continued buildup of the American forces in England (operation “Bolero”) looking toward a landing in Northwest Europe, hopefully in 1943 (“Roundup”). Here, in “Torch,” the Allies had a project that looked difficult but within the realm of the possible to the British and the Americans alike. And the crises on Guadalcanal and in Papua were not allowed to upset the projected operation.

On August 14, 1942, I received a directive from the Combined Chiefs of Staff. It stated that the President and the Prime Minister had decided that combined military operations be directed against Africa as early as practicable, with a view to gaining, in conjunction with the Allied forces in the Middle East, complete control of North Africa, from the Atlantic to the Red Sea … My original directive from the Combined Chiefs of Staff envisaged the attainment to our ultimate objective in three stages: first, the establishment of firm and mutually supported lodgments in the area of Oran, Algiers, and Tunis, on the North Coast, and of Casablanca on the West Coast; second, the use of those lodgments as bases to acquire complete control over all French North Africa, and, if necessary, Spanish Morocco; third, a thrust Eastwards through the Libyan desert, to take the Axis forces in the western desert in the rear and annihilate them. … The aim was thus to insure communications throughout the Mediterranean, and to facilitate operations at a later date against the Axis on the European continent.

Many U.S. strategists and commanders (including the Soviets) had hoped that a massive invasion aimed at northern France could be accomplished by 1943. Toward this end, three variants with the intent of conducting a massive amphibious operation into northern France were in the planning stages, including Operations Sledgehammer, Roundhammer, and Roundup. Instead, at the Second Claridge Conference held in late July 1942, the decision was made to adopt an indirect approach and to place the first American troops into French North Africa in late 1942 with Operation Torch.

Operation Torch

In the early hours of the morning [0500] on 8 November 1942 approximately 90,000 Allied troops, mostly American, disembarked from their landing craft at various points in Vichy French-controlled Morocco and Algeria to begin America’s first major offensive of the second world war, Operation Torch. Simultaneously, pro-Allied guerrilla fighters organized by General William J. (“Wild Bill”) Donovan’s recently formed Office of Strategic Services (OSS) sprang into action to assist invading forces. These men, who had been recruited and armed over the previous three months by OSS agents stationed in Vichy French North Africa, represented part of a new dimension in the field of American second world war military operations, a dimension which, in addition to guerrilla activities, included extensive espionage and intelligence work, especially in the field of assessing enemy motivation, and in the conducting of secret negotiations aimed at creating pro-Allied factions in either enemy or neutral countries.

Operation Torch created three separate task forces: Western, Center, and Eastern, which conducted simultaneous amphibious operations that led to landings at locations near Casablanca, Morocco (Western Task Force—commanded by U.S. Major General George Patton), Oran, Algeria (Center Task Force—commanded by U.S. Major General Lloyd Fredendall), and in the close vicinity of Algiers, Algeria (Eastern Task Force—commanded by U.S. Major General Charles Ryder). The overall objective was to immediately push east and seize the Tunisian port and airfield complex of Bizerte and the capital city of Tunis. Once in possession of those objectives, the Allies would be positioned to conduct aerial bombardment of Axis positions on Sicily, protect Allied seaborne convoys, and attack Rommel’s supply lines.

Within 24 hours, on November 9, Germany dispatched troops from Sicily to Tunisia. Realizing that the Allies were attempting to close in against Axis North African forces and place them between two pincers, that is, the British Eighth Army closing in on Rommel from the East, while the Torch invasion group drove in from the West. Axis commanders were attempting to reinforce the region around Bizerte and Tunis to avoid having German and Italian forces driven off the African continent. At the time, Rommel’s forces totaled 78,000 troops but were in possession of only 129 tanks, and they succeeded in fortifying their positions in Tunisia before the pincer forces converged on their location.

As was originally expected, the first encounter of U.S. Army forces with Rommel’s veterans resulted in defeat for the advancing Americans at the Battle of Kasserine Pass (February 19–24, 1943). After the debacle of Kasserine Pass, command of the U.S. II Corps was given to U.S. Major General George Patton. From that moment on, Montgomery’s British forces essentially “elbowed” Patton’s forces (and vice versa) for the opportunity to attack the retreating Axis forces. As near certain defeat approached, Rommel was moved out of Africa and installed in Europe to direct the expected amphibious assault into northern France. On May 13, 1943, as the British navy was waiting offshore from Tunisia in strength, and after U.S. and British forces had driven the remaining Axis forces to isolated pockets in the vicinity of Bizerte and Tunis, German Lieutenant General Hans-Jurgen von Arnim surrendered his forces. Nearly 240,000 Axis troops were taken prisoners, and 250 tanks, 2,330 aircraft, and 232 ships were confiscated. Overall, from 1940 to 1943, Britain suffered 220,000 casualties, while total Axis losses totaled more than 620,000, which included the loss of three field armies.