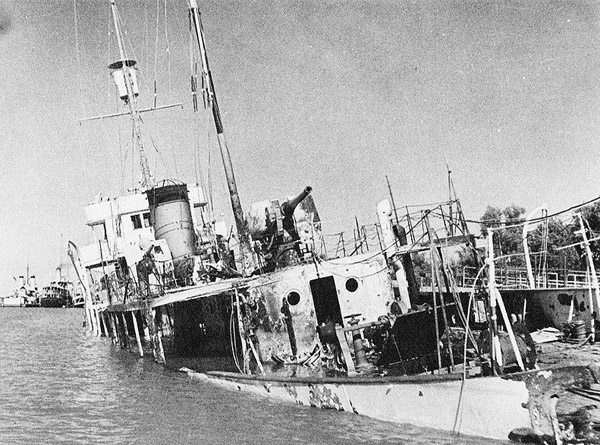

The Iranian warship Babr (Tiger) after being shelled and sunk by the Australian sloop HMAS Yarra during the surprise attack on Iran in August 1941

With the German push eastward during Operation Barbarossa, Britain believed that Hitler’s aim, in addition to destroying the Stalin regime, was to take control of the agricultural land of the Ukraine, the oil fields located in Romania, and the Caspian (Baku, Azerbaijan) and once ensconced in the Caucasus, move south to control Iraqi and Iranian petroleum reserves. In the summer of 1941, while the Axis threat to Iraq and Syria had been significantly reduced, Rommel’s forces in North Africa continued to threaten Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal. As the Third Reich attacked with massive force in Barbarossa and drove toward the Caucasus, London believed German forces had planned on utilizing the Turkish rail network to advance from both the Balkans as well as the Caucasus.

It soon became apparent that German forces under Friedrich Paulus on the Russian front, driving toward the Caucasus, desired to link up with German forces under Rommel, should he be successful in overrunning the British in Egypt and marching into the broader Middle East. The overall strategic hope was to then move toward India and link up with a Japanese empire that was pressing westward across Asia. In the summer of 1941, after the fall of France and after Britain took a savage aerial pounding by the Luftwaffe, the attack against the Soviets brought back memories of the Russians being knocked out of World War I and the full might of the Kaiser being turned westward on Britain and France.

During the Second World War, London began referring to the “Northern Front,” which referred to a line of defense that Allied forces would take given a Soviet defeat at the hands of Germany. Such a defeat would lead to an expected surge of German troops descending into the Caucasus and threatening neutral Turkey and Iran. German leaders once again viewed the use of railways as an opportunity in circumventing British and Allied sea supremacy and allowing Berlin to rapidly project military power inland.

Thus, it became critical that the Soviet Union should be supplied sufficiently to avoid a repeat of the collapse of the Russian Empire, similar to what took place during World War I, which then allowed the Kaiser to turn his resources and attention toward the western front, in general, and toward Britain and France, in particular. In that campaign and following the Russian collapse, Germany was slowly making headway against Allied forces. The collapse of Russia immediately mobilized the United States. The presence of 1.5 million U.S. soldiers coupled with the massive influx of supplies countered the ability of Germany to place its entire focus and resources in the West. If the Soviet Union was knocked out in the current campaign, Britain feared that Germany’s ability to project force across the Eurasian continent via rail would neutralize its traditional sea advantage. The acquisition of Middle East oil and cutting Britain’s lifeline to India would be possible if the Soviets were unable to stand against the Wehrmacht. Accordingly, the Allied strategic imperative became: provide the Soviet army with sufficient resources for it to stand against Nazi Germany and open a second front in the West as soon as possible.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Britain and the USSR became formal allies. These developments led to a joint British-Soviet strategy toward the Caucasus and toward developing lines of supplies from the Middle East to Soviet-held territory in and around the city of Stalingrad. As a result, Iran became a focus for both of these policy imperatives. Reza Shah, ruler of Persia, changed the name to the Imperial State of Iran in 1935, in part to emphasize the Aryan heritage of the country. He did so with the undisguised desire to align Iran closer with Hitler’s Germany and its own predilection for Aryan supremacy. Iran, significantly underdeveloped as the country entered the modern era, made major strides under Reza Shah who sought to improve and modernize infrastructure and transportation networks as well as establish modern schools and colleges. In these efforts, he needed Western assistance to access technology and the learning model that made such technology possible.

However, tensions had been strained with Britain since 1931 when the Shah cancelled a key oil concession (D’Arcy), which provided the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company exclusive rights to sell Iranian oil. Understandably, since it was British capital, technology, and oil expertise that extracted and marketed the oil, Britain believed it deserved the majority share of the profits. However, the 90 percent of the profits that London kept after petroleum sales and after the transactions moved through the British banking system served as an irritant between Tehran and London. By mid-1935, the Shah was increasingly leaning toward Germany for technology and modernization.

As World War II broke out, the Shah declared neutrality but practiced intrigue with the Axis powers. On July 19, 1941, and again on August 17, London sent diplomatic notes ordering the Iranian government to expel German nationals then in Iran, numbering about 700. Unable to convince the Shah through diplomacy to distance himself from the Third Reich, British and Soviet Forces invaded the Imperial State of Iran beginning on August 25, 1941. Final diplomatic notes declaring the commencement of military operations were delivered to the Shah’s government on the night of the invasion by British and Soviet ambassadors. Those military operations (Operation Countenance) would continue until the fall of the Shah on September 1941.

On the night of the invasion, the Shah summoned both of the ambassadors from Britain and the Soviet Union and asked that if he sent the Germans home would the invasion be called off. Neither ambassador gave the Shah the clear-cut answer he sought. Frustrated and concerned, he wrote a letter to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt:

… on the basis of the declarations which Your Excellency had made several times regarding the necessity of defending principles of international justice and the right of peoples to liberty, I beg your Excellency to take efficacious and urgent humanitarian steps to put an end to these acts of aggression. This incident brings into war a neutral and pacific country which has had no other care than the safeguarding of tranquility and the reform of the country.

Roosevelt responded in a note diplomatically alluding to the dangers posed by Hitler’s ambition to all regions of the globe, including North America, and the United States being actively involved in supporting those people and nations then resisting Hitler’s military conquests.

Soviet sphere of influence, Iran, 1946

As Germany invaded the Soviet Union in late June 1941, the apparent drive toward the oil fields in the Caucasus (Baku, Azerbaijan, in particular) and the Caspian Sea became a significant concern. Moreover, the Shah’s Imperial State of Iran completed an 800-mile railway from the Persian Gulf port of Bandar-e Shapur (now Bandar Khomeini) to the Caspian Sea port of Bandar-e Shah in 1938, toward which the Germans had provided significant assistance in terms of engineering and rolling stock. For the Allies, these harkened back memories of the drive to create a Berlin-to-Baghdad railway aimed at offsetting traditional British sea power supremacy and the creation of interior lines for the projection of land power into the Middle East.

During the joint Allied action taken against the Shah beginning on August 25, 1941, 40,000 Soviet troops descended into Iran from the North and marched on Tehran. On the same day, 19,000 British Commonwealth troops, mostly Indian brigades, and as part of Operation Countenance, entered Iran from various directions, with half moving straight for the oil fields in the vicinity of Ahwaz and airborne units moving into Abadan to protect the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s refinery, then the largest in the world. A subsidiary goal of the combined action was to open a supply line utilizing the Trans-Iranian Railway in which to resupply the Soviet army, as it defended against Operation Barbarossa.

Within four days, and as Soviet and British troops backed by airpower rolled up Iranian defenses, the Shah issued an order to his armed forces to stand down and cease military operations against the invaders. On September 17, 1941, the Shah abdicated and was eventually transported to South Africa where he passed away in Johannesburg in 1944. The Shah’s son, the Crown Prince Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, took the oath after the abdication and became the new Shah of Iran. Under a separate agreement, the Soviet Union controlled northern Iran, Caspian ports, and the Iranian-Turkish border, while Britain’s control included southern Iran, Persian Gulf ports, and the oilfields.

The United States began moving supplies to Stalin’s army under the Lend-Lease Act of 1941. In 1942, Roosevelt proposed to Churchill that the U.S. Army become involved in the supervision of the 800-mile Trans-Iranian Railway. On August 22, 1942, Churchill responded in a cable to Roosevelt:

I would recommend that the railway should be taken over, developed and operated by the United States Army; with the railroad should be included the ports of Khorramshahr and Bandar Shahpur. Your people will thus undertake the great task of opening up the Persian Gulf Corridor, which will carry primarily your supplies to Russia … We should be unable to find the resources without your help and our burden in the Middle East would be eased by the release for use elsewhere of the British units now operating the railway. The railway and ports would be managed entirely by your people.

In the fall of 1941, the Trans-Iranian Railway was only capable of transporting about 6,000 tons per month. By the fall of 1943, U.S. Army engineers and contractors had expanded the railway’s capacity to more than 175,000 tons of cargo per month. Under the direction of the U.S. Army, Iranian camel paths were expanded into highways for trucks, and the railway, which had more than 200 tunnels, was reinforced and expanded in order to haul tanks and other heavy equipment over the mountains.

Between 1942 and 1945, more than 5 million tons of desperately needed supplies, including 192,000 trucks, and thousands of aircraft, combat vehicles, tanks, weapons, ammunition, and petroleum products were delivered to the Soviet army through the Persian Corridor.

Oil

The Middle East was only just developing its oil capacity prior to World War II. The first well in the Middle East was drilled in Iran in 1908, overnight elevating the strategic importance of that region. Oil was first extracted from Iraq in 1927, Saudi Arabia in 1935, and Kuwait in 1938. But production was low by world standards and transport difficult and easily intercepted. Still, the presence of oil fields and some production in those areas factored into Britain’s strategic thinking. It contributed to London stationing Indian Army and other garrison forces in-country, sending in Special Operations Executive (SOE) teams and dispatching an armed expedition to topple a pro-German regime in Iraq. Britain also drew oil from Venezuela, which grew rich on its wartime exports. Oil was not discovered in volume in western Canada until 1947. Minor production around the Great Lakes did not even meet Canada’s small wartime needs. That meant British and Commonwealth forces were reliant on American oil. Like the Soviet Union, the United States had vast internal oil reserves. Americans could draw upon over 400,000 oil wells, which produced nearly 700 times as much as Japan’s puny 4,000 wells. Such abundance permitted the United States to provide its oil-deficient allies with crude and refined fuels. However, the United States was late responding to the U-boat threat to its Atlantic tanker traffic. It took months for the U.S. Navy to accept, devise, and deploy a coastal convoy system and find the escorts to make it work. Longer term, the United States solved the tanker problem by building pipelines from its Oklahoma and Texas oil fields and refineries to the large cities and ports of the northeast. Other pipelines carried fuel oil and refined products to the great ports of the west coast, for transhipment to the Pacific.