Of greater import, General Hülsen moved on Zschopau. Henry slowly and deliberately moved to join him, in the process leaving General Itzenplitz with eight battalions and seven squadrons, including two squadrons of the Szekely Hussars, at Zwickau. Itzenplitz was to play the spoiler to any effort in Henry’s direction that Dombâle might try. Henry’s command itself was 14 battalions and 20 squadrons, although this did not include Knobloch’s command. The latter had three full battalions; he set up shop at Freibergsdorf. Itzenplitz’ post was shadowed by Luzinsky, while Dombâle himself moved discreetly on Bamberg (June 20 1758). The latter was marching to join forces with Esterhazy. Dombâle’s forward elements did not even begin to reach Hof until July 1.

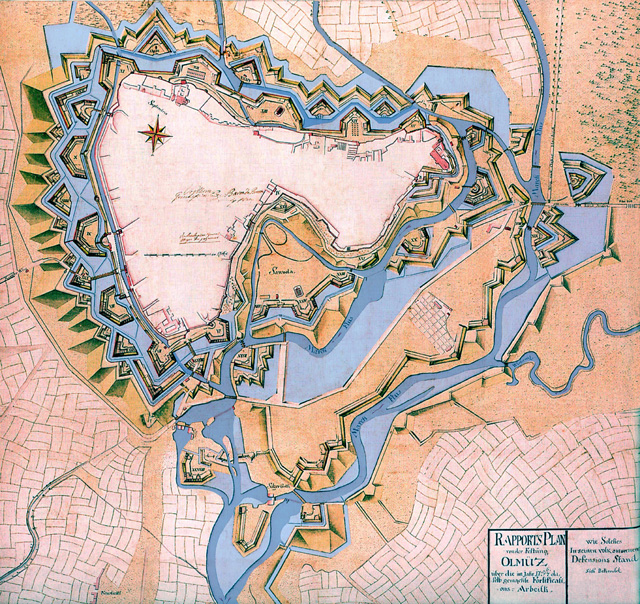

Daun’s task was not easy. Originally, it had been felt wise to give the marshal some leeway about how to relieve Olmütz. However, so soon as Vienna discerned Daun was merely marking time, with scarcely any action planned, orders were sent to him to relieve the garrison in Olmütz. So, while Henry was preparing something in Bohemia, in Moravia, the main Austrian army made ready to move. In mid–June, Daun rose from Gewitsch, detaching 1,100 men, from the command of Bülow, to cross the Morawa to bolster the garrison in the fortifications and make some feints. The detachment brushed Neustadt, and Frederick sent Ziethen to deal with the new intruders. Ziethen failed to intercept it, and the newcomers were able to slip into Olmütz while Daun, begging off, withdrew again into his old lines. The Austrian detachments, under Laudon, had been busy all this while. They regularly struck at the Prussian outposts under cover of night and frequently threw a scare or two into the escorts for the supply trains. Prussian provisions were running low, and in a remarkable twist of events, Prussian deserters began appearing regularly at the gates of Olmütz wanting to get into the city. These raids, however, did little to alleviate the suffering of the defenders of Olmütz, and such half-hearted attempts to draw the attention of the bluecoats elsewhere could not by themselves hope to drive Frederick’s men from the walls of the place.

The siege was making progress all this time. Inside Olmütz, supplies of food and powder were running low, but the Prussians suffered even more from the shortage of ammunition and powder. One final large convoy was to be made up and brought in with all the supplies that Frederick believed his men would need to bring the siege to a successful conclusion. He detailed Lt.-Col. Konrad Wilhelm von der Mosel with a 7,000-man force to escort this final convoy in. To provide additional security against Laudon, who was sure to make an effort to cut off this all-important supply train, the king saw good to detach Ziethen’s men to help shield Mosel’s force.

Mosel was to leave Troppau with the van of the wagons on June 26, according to plan. Ziethen sent Colonel Werner (with 200 dragoons, 300 hussars, and a full battalion of grenadiers) to meet Mosel. Werner moved out from near Olmütz on June 28 to greet the incoming train. Frederick could no more than hope for the best. With this last reinforcement, Balbi promised he could wrestle Olmütz from the enemy in a fortnight. Time was becoming critical now for the bluecoats, with enemies beginning to close in from all sides.

The march of the train started on schedule, but the movement of the double-teamed wagons over the windy narrow roads was slow and cumbersome. A group of 3,000 wagons altogether, with two civilian drivers (although military personnel would have made more sense under the circumstances, had that been the usual procedure) per wagon. As there had been no letup in wagons coming and going across the same routes, the pathways were worn. Heavy rains added further difficulties, and the wily enemy knew about the move almost from the beginning.

The trek was through some 90 miles of twisting, rolling countryside, in territory largely controlled by the enemy. The movement of such a large convoy was a haphazard affair at best, but the efforts required to attack it en route were also not without risk. The whole length of the train varied considerably, at some points being spread out to 30 miles or more from beginning to end, and at other places condensed into less than half that. The forces under the direct command of Mosel were divided into three separate groups: the van; the main body; the rearguard. What was worse, even in a situation where the wagons were close together, there were not sufficient men for a continuous front to provide support between these three bodies of moving men and equipment. The condition of the roads and rain degraded the further they went. On June 27, after just one day on the move, Mosel found it necessary to stop the front wagons of the convoy to give the rearward elements time to close up.

Surprisingly, however, the progress of the trek proceeded much better than could have been expected. The convoy’s escorts hoped the train might be brought through before the Austrians had word of its advent. A forlorn hope! And, for a change, Daun had decided to do something about it. Heretofore, he had not simply ignored the pleas and requests he had received to break up the siege, but cautious Daun was just not willing to risk a major battle over this fortress. He had done precious little in the way of stopping the supply trains without which no siege, no matter how lengthy, could hope to be successful. Any firefighter knows the quickest way to put out a flame is at the source. In a way this analogy was fitting because these supply trains were the source of the Prussian effort before Olmütz; extinguish the source and Frederick’s designs would be ruined.

It was now two choices for Daun: (1) Give battle to relieve the pressure on Olmütz; (2) Stop that last convoy. Not wishing to force a fight with the eager king (at least on the latter’s terms), the cautious marshal chose the second alternative. His plan as formulated was quite simple. From the west end of the Morawa River, Laudon, with his various detachments, was to do all he could to intercept the convoy, while General Siskovics66 was to operate in the Littau-Müglitz country—east of the river—against the Prussians from that end.

Immediately upon giving Laudon and Siskovics their marching orders, Daun marched the main army from Gewitsch near Konitz southward. This latter maneuver caused Frederick to think his foe was at last coming out for a finish fight over Olmütz. The Prussians were encouraged to see Daun’s massed army on the rises across from Prossnitz (June 22) and the king ordered his men to realign their outer lines in preparation for battle. Did the Austrian commander intend to fight? He did not and Daun’s only aim was to send the reinforcements into Olmütz, as well as to divert Frederick’s attention while his subordinates went to smash the convoy.

Ironically, on that same day, the siege took a turn for the better in favor of the bluecoats. Balbi had made an indentation in the defender’s lines (incessant Prussian howitzer fire had opened a widening gap in the earthen fortifications), and was inexorably squeezing the enemy’s presence at the walls into a tightening vise. Daun, who had retired to the south again, crossed the Morawa to steer north to support the impending effort on the Prussian train. Siskovics had reached his appointed posts, and Laudon, moving by Müglitz and Hofberg, made a roundabout path on the western end of the Prussians. From there he moved towards Bautsch (specifically, Güntersdorf) where Laudon intended to perform an unexpected attack upon the supply train from the pass there. As a precaution, Laudon left a force of some 600 men at Domstadl itself, under Major von Goese, to hold a position through which the convoy would come.

Mosel made good progress the first day, but the following day, the halt we have looked at, while probably a normal procedure, gave Laudon the time he required to move into attack position. Otherwise, the Austrians might not have reached Güntersdorf in time. As it was, Laudon arrived there on June 27, and undertook the necessary preparations to ambush the foe in the defile beyond. The following morning, Mosel got on the road leading to Güntersdorf from Bautsch, where he had spent the previous evening.

On approaching the place, Mosel found the enemy drawn out ahead (on the wooded hills above and in the pass in front) intending to dispute his passage. The Prussian commander ordered the train to halt, and, taking his troopers, led a charge that quickly cleared the defile of its occupants. Laudon’s men lost many prisoners69 out of a total of about 500 altogether. The 1st Battalion of Young Kreutz led the initial stroke, pushing through the defile into the enemy’s fire. Once there, the men took up an exposed position hard by. Behind this body, the grenadiers of Billerbeck and Captain Pirch led a part of Prince Ferdinand’s men and the rest of Young Kreutz. Laudon’s most effective measure was to plant a battery confronting the Prussian left. It just so happened that Old Billerbeck was positioned directly opposite the offending big guns. The grenadiers wasted no time trying to silence the Austrian ordnance. The men pressed forward into the woods, overcoming in the process the light irregulars who were supposed to be “protecting” the approaches to the battery. The crew of the guns, and the regulars who were with them, were not so readily inclined to go. Billerbeck promptly put in a determined charge at the point of the bayonet, which drove off the enemy, took one gun from its desperate crew, and captured some 200 men.

With the offending Austrian battery silenced at last, the Kreutz and the Prince Ferdinand regiments took their turn. A most determined effort now ensued, in which the latter two Prussian units sought to match the achievement of Old Billerbeck. Laudon did all he could to shore up his lines, calling upon his men for a supreme effort. But, after losing another of his guns to the advancing bluecoats, Laudon saw the contest was lost. Reluctantly, he ordered his tattered men to fall back on Bährn. The Austrian commander’s behavior had been almost impeccable, but there was no denying his force had suffered a serious drubbing. Losses were nearly 500 men. Fifty-two men were dead, approximately 340 were prisoners, the rest wounded.

Mosel was in no condition to follow up his advantage, as he most correctly did not lose sight of his more important mission of the safe conduct of the convoy. There had been some ill-effects from the action. The sounds and smells of the spectacle of artillery fire had unnerved many of the civilian crews. Some of their number took to horse or feet and started back on Troppau, leaving some of the wagons without crews, while the Prussians were taking care of Laudon. This vacuum left the irregulars, those who had not been chased away, the opportunity to break into the train. The bluecoats who had just chased off Laudon’s men at the defile then had to return to chase away the irregulars from the convoy’s vicinity.

It occurred to Mosel the king needed to be informed about the progress of the supply train. He disptached a trusted aid, named Beville, to go to Prussian headquarters. Meanwhile, after the convoy had been righted again as much as was possible, Mosel pressed on for Neudörfel. When Ziethen momentarily joined up with the train, he discovered that much more needed to be done with the wagons. As it worked out, “every single wagon had been turned around to go back the way they had come.” This would simply never do. Calling off of the march for a day was a necessity. In the present state, the train would never have reached its destination even without further enemy interference.

Laudon would still have made his main attack there had he not known of a more appropriate defile not far from Güntersdorf. A short distance from the little village, there arose a short knoll to the right of the roadway. This gave way to a pair of hills protruding not far from the Domstadtl River; rises which were separated by a large wooded hollow which the pass went through.

This defile, known to history fittingly as the Pass of Domstadtl, was the place that Laudon now selected for the main effort against the convoy. Ziethen had recovered his detachment under Werner, which had only reached Gibau anyway, accompanied by the grenadiers of Manteuffel and General Kaspar Rudolph von Unruh. Ziethen, as soon as he reached Gibau, was rewarded with the bad news that Mosel’s forward progress had come to a virtual halt. The horizon showed smoke and there were sounds of a struggle of some sort in Mosel’s direction. Not more than half the wagons had caught up with Mosel, which had caused the day of rest. The horses were exhausted and many of their guides were either missing or else wished they were.

At dawn, June 30, the convoy moved out again. Ziethen and Mosel had decided to take precautions as they approached the Pass at Domstadtl, where they rightly assumed the foe would make another attempt to ambush them. Ziethen’s cavalry was on the right side of the convoy, this being the direction from which the enemy might reasonably be expected. The foot soldiers were on the left, and the escort forces were fanned out enough to maximize their efforts.

As quickly as the advanced wagons of the convoy drew within sight in the early afternoon of June 30, Laudon (who had been joined in the meanwhile by Siskovics and his men) opened on them with his small guns and massed musketry fire. The Austrian mounted men were ordered to block the pass itself. The Prussians approached with the infantry escort still strung out, and the train divided into separate groups. The advanced guard was under General Krockow. The latter promptly rushed forward, cleared the way of the enemy, and managed to push some 250 of the wagons through before Laudon and Siskovics could seal off the penetration. Then Krockow halted his wagons to await the outcome of the struggle.

The Austrian advanced batteries on the leftward rises promptly opened a heavy fire upon the desperate Prussian force below. The small arms fire concentrated on killing the horses, without which the convoy could not proceed. Ziethen’s men, led by the dogmatic Puttkammer, then charged the Austro-Saxon force. This fired up body crashed into Siskovics’s first line, which was sent reeling. Then an enemy force of dragoons burst forth, surrounding the Prussian force. In heavy fighting, the stunned grenadiers cut their way through the enemy and retreated to the “security” of the convoy. This was not a done deal. Laudon, with his force, suddenly emerged on the right. This latter body crashed into the convoy from a new angle. Laudon was particularly determined, and a most obstinate Prussian force was finally overcome by the combined efforts of both allied parties. Finally, the bluecoat force fragmented, allowing the enemy to break in upon the train.

Ziethen, meanwhile, charged again and again to puncture the enemy ring of defenses, with little success. He had the wagons formed into a square (a Wagenburg) to resist the allied strokes. Ziethen’s horsemen surged forward and swept back the foe from the hills, but lost his ground again to counterattacks. It was clear Prussian resistance was indeed stubborn, and the artillery that was at hand unleashed a heavy fire to try to force the allies from the ravine.

At length, Ziethen discovered he had Laudon on one side and Siskovics on the other, and the wagon train was hopelessly bogged down. The prospects for rescue were growing dim.75 In desperation, he abandoned the wagons and, cutting his way through the enemy’s lines, made for Troppau. The entire train was captured, save for that small group rescued by Krockow.

The latter determined to press on, so as to fulfill the mission to the extent now possible. As Ziethen was retreating in the other direction with most of the escort force, it was not long at all before the rather energetic enemy once again appeared, to complete the overthrow of the force trapped at the pass. Scouts reported that allied celebration of their success, which Krockow could do nothing about at the moment.

Any delay did nothing but risk another enemy effort to finish the job. So the greatly reduced supply train lunged forward. By evening, the convoy was near Bistrowan. At Heiligenberg, a new enemy effort indeed was made. This one was far less involved, but the attackers did snare one more wagon. The remainder reached the main Prussian lines.

Prussian losses for the escorting force were approximately 2,386 men; allied casualties were approximately 600.77 One of the most valiant tales associated with this action was the bravery of new recruits of the ranks of the Ferdinand Regiment. “Those inexperienced lads, varying from 17 to 20 years, defended themselves to the last.” Some 900 of these brave youths were at Domstadtl; only 67 passed into captivity. Except for a few wounded survivors, all of the rest perished that day at the pass, almost all of them fighting in a sustained action for the first time. Captain Pirch was among that number. The capping of the Prussian defeat in this melée was in the terrible execution of the Austrian guns, which speedily gained the upper hand.