The large Byzantine army intended to strengthen the fortifications of the eastern frontier and to invade Turkish Syria. The wild Turkish tribes who were raiding the empire could probably not have opposed this assault, but Alp Arslan was drawn into the fray by the threat to the Seljuk lands.

The Emperor of the Romans was led away, a prisoner, to the enemy camp and his army was scattered. Those who escaped were but a tiny fraction of the whole. Of the majority, some were taken captive, the rest massacred. MICHAEL PSELLUS, CHRONOGRAPH/A, 1018-79

At Manzikert the Seljuk sultan of Baghdad, Alp Arslan (1063-72), decisively defeated the Byzantine emperor Romanus IV Diogenes (1067- 71), opened the way for the Turkish domination of Anatolia and ultimately triggered the Byzantine appeal for aid which gave rise to the First Crusade in 1095.

The Turks were a pagan Steppe people who attacked Islam on its northern frontier. As brilliant horse-archers, many were taken into the service of the Caliph of Baghdad and other Muslim potentates. Long contact converted the Turks to Islam. In 1055 Muslim Seljuk leader Tughril Beg captured Baghdad and brought an end to the Buyid dynasty. Initially they did not seek war with the Christian Byzantine Empire, but such a clash became more likely as Seljuk power expanded into the dissident Byzantine border province of Christian Armenia. From Armenia, marauding Turkish forces penetrated central Anatolia and even reached the eastern Aegean Sea. The leading member of the Seljuk family ruled as Shah. Many of the tribes resented Seljuk domination and attacked Byzantium, where their Muslim zeal as new converts provided a religious cloak for their natural raiding ways. In 1057 they sacked Melitene (Malatya), in 1059 Sebasteia (Sivas) and by early 1060 were savaging eastern Anatolia.

This came at a difficult time for the Byzantine empire. Its hold on south Italy was threatened by rebellious Norman mercenaries, while Patzinacks from the Steppe attacked the Balkans. The Macedonian dynasty had died out shortly after the death of Basil II (976-1025) and no dominant emperor emerged who could impose his dynasty. As a result there was bitter rivalry between the great noble families. There were no fewer than thirty rebellions in the period 1028-57, and the frontiers were stripped of troops to put them down. In eastern Anatolia weak central government gave rise to turbulence as the numerous Armenian and Syrian Christians feared that Constantinople aimed to impose religious unity upon them. The imperial army was a mercenary force and extremely expensive, so military expenditure was cut or expanded at the whim of emperors. Constantine X Doukas (1059- 67) was the head of a great noble family and on his deathbed he vested power in his wife to rule on behalf of his son. But the rule of a woman in such difficult times was not acceptable and she married a successful general, Romanus IV Diogenes. The Doukas family regarded him as merely guardian of their succession, but when he produced two sons they began to fear for their position.

After rebuilding the Byzantine Army, during 1068-1069 Romanos conducted a series of successful campaigns against Seljuk sultan of Baghdad Alp Arslan (the “Brave Lion”), forcing him back into Armenia and Mesopotamia. Romanos then campaigned in Syria, which had taken advantage of Seljuk successes to rise against Byzantium, but returned to eastern Anatolia to defeat the Ottomans in the Battle of Heraclea (Eregli) in 1069. Alp then withdrew to Aleppo. Romanos again controlled Armenia except for a few Seljuk fortresses.

In 1070 Romanos shifted his efforts to Italy. He enjoyed some success against the Normans, but a renewed Turkish threat against eastern Anatolia forced him to withdraw, and in 1071 the Normans conquered southern Italy completely. The Anatolian threat took the form of two Turkish armies under Alp and his brother-in-law Arisiaghi. Alp took the Byzantine fortress city of Manzikert but was repulsed at Edessa (Urfa). Arisiaghi meanwhile defeated the principal Byzantine force under Manuel Comnenus near Sebastia.

The campaign and context of the battle

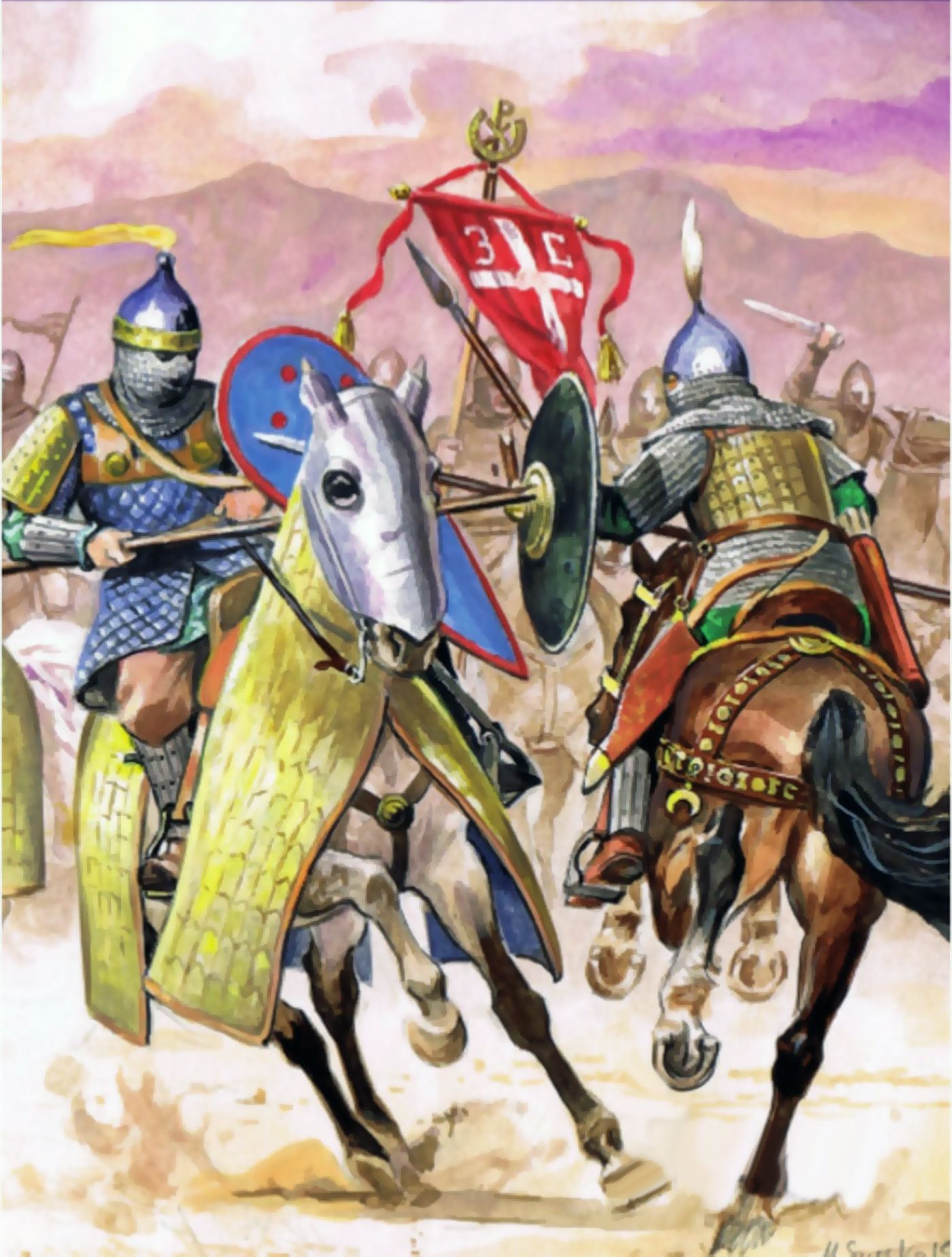

Romanus’s prestige depended on him successfully dealing with the Turks. It was suggested that he reduce to a desert the eastern provinces across which they raided, but he was reluctant to do this. He preferred to force the Shah to curb the raiders by attacking Syria in great military expeditions, as in 1068 and 1069. Alp Arslan was preoccupied in attacking Egypt where a dissident Caliphate had formed a rival centre of power, and had no wish for war with Byzantium. However, when Romanus mounted a great expedition in 1071 he could not ignore the threat. On this occasion a huge Byzantine army, perhaps 40,000-60,000 men, was raised – a mixed force of native levies and mercenaries. Amongst the native units the emperor’s Varangian Guard and a few others were of high quality, but the Armenians and Syrians were unwilling soldiers. Amongst the mercenaries there were Frankish, German and Norman heavy cavalry and Turkish light cavalry. During the march the Germans had attacked the emperor in pursuit of claims to wages, while there had been frequent clashes with local Armenians.

Arriving in eastern Anatolia, Romanos dispatched an advance force under General Basilacius to the vicinity of Seljuk-held Akhlat to ravage that area and serve as a screen for his own force. Romanos laid siege to and took Manzikert, then moved to besiege Akhlat. He sent Basilacius toward Khoi, in Media, where Alp was reported to be assembling a large army.

In late July or early August, Alp’s army of 50,000 or more men brushed aside Basilacius’s covering force of perhaps 10,000-15,000 men. Basilacius then withdrew his men to the southeast without informing Romanos. The reasons for this are obscure but are believed to have been prompted by a treachery including Basilacius; Romanos’s second-in-command, Andronicus Ducas; and Empress Eudokia.

Turks

Almost entirely cavalry, especially mounted archers

Commanded by Seljuk sultan of Baghdad, AlpArslan

Unknown casualties

Byzantines

40,000-60,000 men: natives- Varangian Guard, Armenians, Syrians; mercenaries – Frankish, German, Norman heavy cavalry, Turkish light cavalry; elite units mounted; some heavy cavalry

Commanded by Byzantine emperor Romanus IV Diogenes

Unknown casualties

The battle

Before Romanus attacked Manzikert, where resistance was weak, he sent his best troops on to Chliat under General Joseph Tarchaniotes. He divided his army in the belief that Alp Arslan was in retreat. In fact the sultan gathered a small but efficient force of Turkish cavalry and surprised Romanus’s troops, whose anxieties were increased by the desertion of many of their own Turkish troops. But Alp Arslan was aware of his weakness and offered to negotiate. Romanus, however, needed a victory to shore up his prestige and knew the Turks were few. Accordingly, he deployed his army with Nicephorus Bryennius on the left, himself in the centre and a leader called Alyattes on the right. Andronicus Doukas commanded the reserve. The army advanced with the cavalry to the fore and the heavily outnumbered Turks retreated.

As evening approached, Romanus gave the order to turn back to the camp, and his division did so in good order. Those more distant from Romanus were uncertain of what was expected of them, and so they believed the story spread by the fleeing Andronicus that the emperor had been defeated. These confusions augmented the tensions within the army and a general flight began, led, we are told, by the Armenians. The astonished Turks slaughtered the fleeing troops while Romanus and his division fought bravely, but ultimately had to surrender. The main force of the Byzantine army at Chliat, including the Franks, Normans and Germans, had simply fled when they heard that Alp Arslan was nearby. The Byzantine defeat illustrates the difficulties of controlling a large army, in this case made worse by its diverse nature and the forces of treachery.

Significance

Although Manzikert was a heavy defeat, it need not have had serious consequences. Alp Arslan freed Romanus in return for tribute and the dismantling of Byzantine fortresses. But the emperor’s enemies then blinded him and renounced the treaty, recognizing Michael VII Doukas as emperor. But he was not a strong ruler. The empire divided between feuding families who frequently called in the Turks.

Anatolia was effectively given away to a series of Turkish war lords. Dissident Seljuks ruled the greatest of these principalities, based on Nicaea and Iconium, the Danishmends controlled the area around Erzincan, the Menguchekids around Erzurum, while a Turkish prince held Smyrna and Ephesus. Alexius Comnenus (1081- 1118) managed to hold the empire together by an alliance with the other great families. The empire remained rich, but Alexius lacked troops and was thus frustrated in his attempts to reconquer Anatolia. When the great Seljuk sultanate of Baghdad began to break up after 1092 he asked Pope Urban II (1088-99) to help him raise mercenaries, influencing westerners with terrible tales of the sufferings of Christians under the Islamic yoke. This inspired Urban II to launch the First Crusade which would have such consequences for the Byzantine empire.

References

Friendly, Alfred. The Dreadful Day: The Battle of Manzikert, 1071. London: Hutchinson, 1981.

Kaegi, Walter E. Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Treadgold, Warren. Byzantium and Its Army, 284–1081. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995.