Lockheed C-5 Galaxy (1968)

Berlin Crisis 1961

In previously highly-classified documents recording the meeting in Washington on 5 April between the newly-installed Kennedy Administration and the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and senior members of his Cabinet the matter of just how far those contingency plans should go was debated. In the course of the meeting a specific agenda topic on Berlin was discussed.

Dean Acheson, acting in a personal capacity as an advisor to the President on the subject of Berlin, outlined his position on the current situation. He asserted that ‘the Soviets would press the Berlin question in the course of 1961.’ He went on to say that ‘we should not wait for the crisis to come upon us. Berlin was the key to Germany and to Europe.’ He also noted that political and economic measures taken against the Soviets if they decided to ratchet up the pressure on Berlin again would be insufficient to resolve any situation. The military instrument of power would also need to be engaged.

Acheson’s predictions proved to be true. Within weeks of the meeting the building of the Berlin Wall had started. Towards the end of 1961 another confrontation developed over Berlin. This one saw over sixty American and Soviet tanks confront each other as the Berlin Wall was erected.

Acheson announced that he had initiated a number of studies looking into the ways in which the west might be able to confront any new move on Berlin by the Soviets. He opined that while those studies had not concluded anything yet, he foresaw difficulties if air power alone was to be used as the primary military instrument of power. His thinking clearly involved a fairly large-scale land component. He thought that surface-to-air missile systems had reduced the manoeuvre room in the air domain.

In his analysis Acheson would have been influenced by the shooting down of Gary Powers over Russia nearly a year earlier. That was quite a shock to the Americans. If the fast and high-flying U-2 could be shot down by a SAM, a slow transport aircraft flying into Berlin would be an easy target. In 1948 that had simply not been a threat that had to be considered.

Acheson went further in his analysis, looking at the possibility that fighter jets might escort transport aircraft on their re-supply mission. He ventured the view that the Soviets would simply pick off the transport aircraft and leave the fighter jets alone. He saw the solution in a large land-based formation heading up one of the main road links into Berlin. President Kennedy expressed doubts about this, noting that he thought the land-based element was ‘not strong enough’.

The minutes of the meeting showed that Harold Macmillan was not enthusiastic about a land-based approach. He argued for a wait-and-see approach adjusting the reaction to the specifics of the situation. Reading between the lines Macmillan was not quite so ready to give up on the element of air power.

In the meeting President Kennedy was clear about the need to maintain the freedoms of the people of Berlin. In his election campaign he had suggested that Berlin be given the label of a free city, borrowing ideas that created special trading situations for some ports called Free Ports. It was a hugely significant moment. The Soviets rejected the idea out of hand. As the Cold War went into the freezer, with the creation of the Berlin Wall the threat to encircle and cut off Berlin raised its head again.

In his first meeting with the Soviet President Khrushchev in Geneva in June 1961 the Soviet leader had proposed that western military forces leave Berlin. Using polite diplomatic language President Kennedy declined, highlighting the importance of the people of Berlin to the Americans.

Had that become yet another crisis air power would have undoubtedly played a role in trying to bring the situation back under control. In October 1961 as Soviet and American tanks were deployed on each side of the famous crossing known as ‘Checkpoint Charlie’, it appeared yet again that the world stood on the edge of another major war. A year later as the Cuban Missile Crisis developed Berlin was again at the centre of the wide-ranging considerations that were discussed. It was possible that the whole crisis in Cuba had been brought about simply to create another excuse to see Berlin integrated into the Soviet Union.

That crisis was narrowly averted. In November 1961 a US intelligence report classified as secret provided summary of the situation around Berlin. The Allies were clearly watching the Soviet Union military force readiness levels to try to obtain any indications or warnings of their intent. It was yet another moment in which the thermometer recording the temperature of the Cold War showed an increase in temperature.

To place his own views on the table President Kennedy quickly arranged a visit to Berlin. His remark in a speech given at the symbolically significant Brandenburg Gate ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ (‘I am a Berliner’) was greeted with huge enthusiasm.

As the Cold War started to thaw it was the location where another American president was to issue a call to the Soviets to put actions behind their political détente. When Ronald Reagan called on the Soviet President to ‘tear down this wall’ he was using the historical context of President Kennedy’s original speech. Throughout the Cold War Berliners were quite literally in the front line of the ideological fault line that existed between communism and capitalism.

Shorts Belfast aircraft

Withdrawal East of Suez

As the sun started to set on the British Empire it became a political and economic imperative for the United Kingdom to pull out of its military bases in the Far East. That withdrawal from the strategic commitments in the Far East was facilitated by a combination of air and sea power. At the time, in the 1960s and early part of the 1970s, the RAF’s strategic heavy-lifting capacity was provided by a fleet of ten Shorts Belfast aircraft. The largest of the operations conducted by the Belfast fleet took place in November 1967 as British forces left Aden. Two Belfast aircraft participated in an orderly evacuation from the area that saw over 6,000 troops and 400 tonnes of equipment moved to an initial staging-post at Bahrain or directly on to the United Kingdom.

The sheer size of the payload bay in the Belfast allowed it to carry a wide variety of loads. Its first mission saw three Westland Whirlwind helicopters and their support equipment rapidly mobilized from Guyana to Fairford, staging through Barbados and Lajes in the Azores. The distance travelled in the mission was 5,200 miles. On landing the aircraft was quickly turned around to deliver two larger Westland Wessex helicopters to RAF Akrotiri. Tensions in that area of South-East Asia had occasionally required the RAF to respond quickly, increasing the military resources in the region. The Belfast fleet was ideally suited to provide that kind of strategic heavy-lifting response.

In the early part of its career the Belfast fleet had distinguished itself in the role of delivering humanitarian relief aid. In March 1968 a Belfast airlifted what at the time was a record payload of 70,682lb (around 31 tons) of Red Cross medical supplies from Changi to Saigon. That record lasted just over a year before another Belfast moved a heavier load in the course of a NATO exercise, beating the previous record by 1,500lb (total of around 32 tons). In the coming months and years these records were also beaten on specific missions.

In 1970 another Belfast flew relief supplies into Romania which had been hit by torrential rain and subsequent flooding. In 1974 responding to yet another emergency relief operation in Africa four Belfast aircraft were deployed to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia.

In what would be a forerunner of the aero-medical evacuation missions now flown by the C-17, a Belfast was used to move a seriously ill small boy from RAF Akrotiri to the famous children’s hospital at Great Ormond Street in London. The baby was accompanied by a medical team to provide care throughout the flight.

The Yom Kippur War 1973

The initial onslaught at the start of the Yom Kippur War caught the Israeli political and defence leaders off guard. Secret planning by the Egyptians and Syrians had maintained a blanket over their real intentions. In the days leading up to the outbreak of war the mobilization of the Egyptian ground forces had been touted as an exercise. For once, the famous Israeli intelligence services were surprised. Along the disputed territory of the Golan Heights the scale of the problem rapidly became apparent: 180 Israeli tanks faced 1,800 Syrian tanks. In the Sinai, due to the religious holiday in Israel, 436 soldiers faced 80,000 Egyptians.

The swift advance by the Egyptian forces into Sinai was supported by a shield of Russian-supplied mobile SAM systems. As Israel brought its tactical air power the mobile SAM systems took their toll. The Russian SA-6 (NATO Code Name: Gainful) was particularly effective. The signature of the guidance radar was not initially programmed into the radar warning receivers flown on the Israeli aircraft so the pilots had no idea they were being illuminated. While Israeli losses in the early stages remain the subject of historical debate, it is widely believed a total of around forty F-4 and A-4 aircraft were lost in the opening salvos of the campaign.

Over the first week of the war over 1,000 SAMs were fired by the Egyptians and Syrians. Syrian air power was also brought to bear with over 100 aircraft taking part in initial combat operations designed to neutralize Israeli command posts.

The Israelis desperately needed ways to counter the effects of the mobile missiles. Initially they mobilized their small military and civilian air fleet to bring in supplies from the United States. However, the capacity of El Al’s 707 and 747 jets was far too small, given what was unfolding. The very future of Israel was at stake.

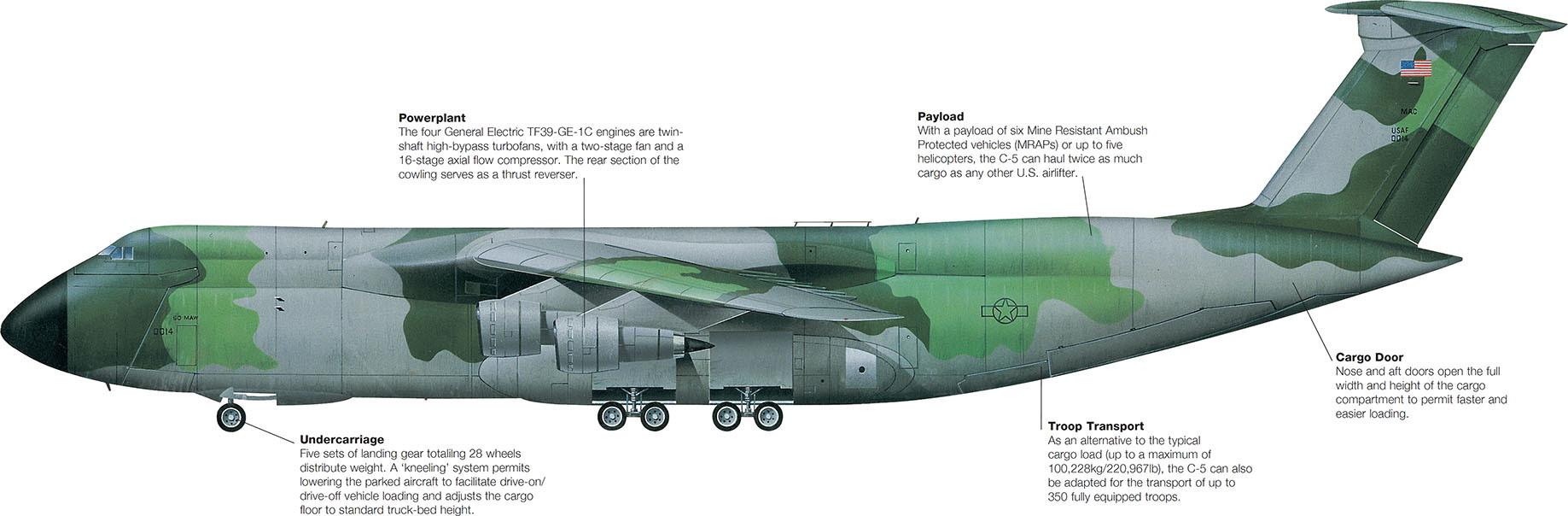

In what is a largely unheralded response the Americans quickly mobilized a huge airlift of advanced sophisticated counter-measures and new weaponry to help replenish war stocks that were becoming rapidly depleted. This massive airlift was mobilized within days and saw C-5 Galaxy and C-141 Starlifter aircraft flying over the Atlantic via the Azores into Israel. KC-135A tanker aircraft were also deployed to create an air-bridge from America to Israel. This facilitated around thirty strategic transport aircraft to fly the route each day. The KC-135s supported the movement of A-4 and F-4 aircraft directly from the factory in St Louis, Missouri to Ben Gurion Airport.

It was called Operation Nickel Grass. It saw over 22,000 tons of military aid flown into Israel by C-5 Galaxy and C-141 Starlifter aircraft, and lasted for a month from 14 October 1973. By sea the Americans also delivered an additional 33,000 tons of supplies. In parallel the Soviet Union undertook its own re-supply mission to assist Egypt and Syria.

The scale of the support task was also huge. As the vulnerable transport aircraft flew along the Mediterranean Sea into Israel they were escorted by fighter jets from the United States navy provided by the 6th Fleet. As the transport aircraft got to within 150 nautical miles from the coast, Israeli fighter jets mobilized to escort them into Ben Gurion International Airport. To provide protection to the air-bridge an American warship was located every 300 miles along the Mediterranean to provide radar coverage of the area. These were backed up by aircraft carriers.

In addition to equipment that would be flown on the strategic heavy-lifting fleet the Israelis also requested new aircraft to replace those lost in the early hours of the campaign. Within hours two F-4 Phantom jets a day began arriving in Israel, having flown non-stop from the United States. In total forty F-4 Phantom aircraft were delivered directly into Israel. As the American pilots landed, Israelis took their place in the cockpit and started flying missions. Thirty-six A-4 Skyhawk jets were also flown in via Lajes and were refuelled by tanker aircraft operating from the aircraft carrier the USS John Kennedy. In addition, twelve C-130E Hercules aircraft were provided to the Israeli Air Force.

History will show that Operation Nickel Grass saved the Israelis from a dire situation that was getting more difficult by the hour. In 1973 the application of strategic air power helped Israel initially to stabilize the situation before being able within a matter of hours to go onto the offensive. Since then nothing of a similar ilk has occurred. The airlift of French forces into Mali in January 2013 was supported by the United States and the United Kingdom with small numbers of C-17 aircraft. In the future similar deployments may well occur. While warfare is always unpredictable, an airlift the size of Operation Nickel Grass is unlikely ever to be repeated.

However, in such an uncertain world that may be a foolish assessment. With China increasingly asserting what it believes to be its territorial rights over the vast reaches of the South China Sea it is conceivable that the security situation in South-East Asia could quickly deteriorate. This time the strategic airlift could well be mounted across the Pacific, staging through Hawaii and Andersen Air Force Base into Taiwan, Korea or Japan. However unlikely that may seem, if it were to occur it would again be an opportunity for those who advocate the merits of air power to demonstrate just what can be achieved in a short period of time. For any planners involved, a good look at Operation Nickel Grass would be an excellent case study.

Operation Desert Shield 1991

When Iraqi tanks mounted their surprise attack in 1991 on what they regarded as territory that was rightfully theirs the potential for that invasion to go beyond the border of Kuwait into Saudi Arabia was very real. This was an international crisis that had simmered for a period but few analysts thought Saddam Hussein would actually dare to invade Kuwait. Iraq was only just starting to recover from its debilitating war against Iran. Iraq’s dire economic situation, however, and a long-standing dispute with the Kuwaitis over oil rights in the region were enough to tip the balance.

On 2 August 1991 Iraqi forces crossed the border into Kuwait. Within a matter of hours the Kuwaiti armed forces had been overwhelmed. At that moment a shocked international community went into political meltdown. They had never expected this to occur. Despite the usual political and diplomatic problems that surround such situations that inevitably result in procrastination and obfuscation, a United Nations Resolution was quickly passed. The international community decided that this act of war would not stand.

That Saddam Hussein’s forces stopped on the border allowed the Americans time to assemble an international coalition that would ultimately see the Iraqis ejected from Kuwait. The political and diplomatic signals emerging from Baghdad at the time were mixed. It appeared that Saddam Hussein, having secured his objective, was prepared to discuss withdrawal. Pictures emerging from Kuwait, however, suggested that the Iraqis were brutalizing the Kuwaiti people who were mounting resistance to the occupation.

History shows that Saddam Hussein was in fact cleverly playing for time in the hope that international efforts to remove his forces from Kuwait would fail. In such situations air power offers an immediate demonstration of resolve providing a defensive screen. It also carries the threat of offensive action.

In halting at the border Saddam Hussein must have concluded that the international community would not bother to come to the aid of Kuwait or would be unable to bridge the obvious fault lines that appear in such situations. He must have reasoned that to have gone further into Saudi Arabia would have caused international consternation. He recognized that red line and chose not to force the issue. It is highly likely that Saddam Hussein believed that the Americans would be incapable of creating an international coalition to oppose him. That President Bush was able to achieve that, skilfully balancing the mix of nations participating in that ad hoc coalition of the willing, must have come as a huge surprise in Baghdad.

Assembling a coalition of the willing takes time. With Iraqi tanks poised on the border with Saudi Arabia and specifically within a short distance of the major oil fields in the north-east of the country a pre-emptive attack aimed at annexing the oil fields could not be ruled out. While diplomats played their cards at the United Nations the American military went into action to place a red line opposing Saddam’s forces. Air power was to be the military instrument that would provide the first line of defence of Saudi Arabia.

Once the immediate threat of an invasion of Saudi Arabia was removed the international community could then turn to the diplomatic and political instruments of power to establish a plan for restoring the government of Kuwait. First things first: the 900-km border between Iraq and Saudi Arabia had to be defended.

To mobilize troops, tanks and equipment into a country such as Saudi Arabia takes time. When coalitions get involved it becomes even more difficult. United States military doctrine is based upon the availability of a Time-Phased Force Deployment List (TPFDL). Despite the United States military having a draft plan for such an emergency as an invasion of Kuwait (Contingency Plan 1002-90), no TPFDL existed. It took until the end of September to build up a balanced capability in theatre that would have been able to mount an operation to remove Saddam’s forces from Kuwait.

In launching Operation Desert Shield the United States military had to start to move a range of equipment quickly into Saudi Arabia. Permission to start moving equipment was sought and quickly granted. The Saudis were fearful of Saddam Hussein’s intentions. The deployment order for Operation Desert Shield was transmitted on 7 August at 0050Z.

The first USAF units had been mobilized into the Area of Responsibility (AOR) within twenty-four hours of the signing of the order to deploy. This was a squadron of the versatile F-15C air superiority fighter. They landed at the Dhahran Airbase in Saudi Arabia. By the end of the first week five fighter squadrons of 112 fighter aircraft (comprising a mix of F-15E, F-16, F-117A, A-10 and F-4G) and fourteen B-52G conventional bombers, seventy tanker aircraft and the first elements of the command and control systems had arrived in the region. Of itself, that was a huge effort. In such chaotic situations everyone believes their piece of equipment has priority on the next strategic transport aircraft flying over the air-bridge. It is understandably a logistical nightmare. However, that was simply the start of a major airlift into the AOR.

To support these initial forces an air-bridge had to be created from the United States into Saudi Arabia. A number of options were looked at in the first few days before the signing of the deployment order. In the immediate aftermath of the war the think-tank RAND (Research and Development) was asked to look at the initial deployment and develop some recommendations for any future operation of this type. Their report documents the planning options being considered at the time. One envisaged sending either eight F-15Cs or twelve F-16Cs to the AOR. Airborne Early Warning and Control Systems (AWACS) were also a priority, along with a Rivet Joint ELINT platform. This would have required the USAF Military Airlift Command (MAC) to mount the equivalent of 395 C-141 Starlifter sorties to deploy those assets into the AOR.

An air-bridge of this size and undertaking will naturally suffer from bottlenecks that constrain its throughput. In-flight refuelling provides a minimum capability to move some equipment directly into the AOR, but that can only be sustained for a short period of time.

To create a flow of equipment into an AOR requires the air-bridge to overcome limitations such as ramp space in transit airfields, fuel availability, cargo-handling equipment and capacity on runways. These are all obvious operational limitations that political leaders may overlook when it comes to ordering the military to undertake a specific tasking.

Manpower is also important and quickly President Bush invoked the call-up of 200,000 reservists. This enabled the constraint on the numbers of air-crew to be quickly solved. Inevitably, as defence spending comes under pressure in the western world, this model of having trained reservists ready to go into action when crisis situations develop is going to become more attractive. The United States has this built into its war-planning. Other countries are likely to follow this approach.

The airlift to support Operation Desert Storm (as ‘Desert Shield’ became) surpassed the sortie generation rate for the Berlin Airlift. By the end of September over 3,800 missions had been flown by both military and civilian aircraft over a fifty-five-day window. This is an average sortie generation rate of sixty-nine aircraft a day. Over 130,000 passengers had been moved into the AOR. That was also accompanied by 124,000 tons of cargo. This is an average daily movement rate of 2,486 passengers and 2,285 tons of cargo. In this period the RAND analysis suggests that the airlift moved 17 Million-Ton-Miles per day (MTM/d) on average. This did not fulfil the figure of 23 MTM/d mandated by Congress.

The main burden of the airlift fell to the C-141 Starlifter and the C-5. Throughout August the C-141 maintained an average of forty sorties a day. Its peak of sixty sorties in a day occurred in the middle of September. By contrast the C-5 averaged fifteen sorties a day with a peak of twenty-five in the very earliest part of the operation. By the end of the first sixty days RAND reports that 3,839 strategic airlift sorties had been undertaken. This had shifted 124,000 short tons of cargo and 134,215 passengers. At the sixty-day point USAF had fielded eighteen tactical fighter squadrons, twenty B-52Gs, ninety-nine KC-135 tankers and ninety-six C-130 tactical transports plus a range of other air capabilities.

In contrast the daily airlift into Berlin during the summer months of 1948 was around 5,000 tons of cargo. In terms of aircraft involved, the arrival rate of aircraft into Berlin was sustained at over 1,400 sorties a day for a long period of time. The payload-carrying capacity of the aircraft involved, however, was far less than their contemporaries. Counting the mission generation rate as a comparator the Berlin Airlift easily surpasses the effort to build up forces in Saudi Arabia.

Air-Bridge Afghanistan

When a country, such as the United Kingdom, commits nearly 10,000 members of its armed forces to a war in a country many thousands of miles away from home it inevitably has knock-on effects. The air-bridge into Afghanistan is flown by a variety of aircraft that perform slightly different roles. The Tristar provides the trooping flights. That enables force rotations to occur, moving significant numbers of people into theatre and returning others home at the end of their tours or returning them home briefly at the mid-point of their tours of duty. Staging through the airfield in Cyprus the outbound and homebound flights last between ten and twelve hours.

To back up the trooping capability the RAF operates the C-17. Its main role is to move equipment into theatre over the air-bridge. A simple testament to the workload placed on the C-17 is that any visit to RAF Brize Norton, the United Kingdom airhead, rarely finds a C-17 on the ground for very long. These are the workhorses of the air-bridge as far as the movement of equipment is concerned. To maintain a force in Afghanistan the C-17s are operated at a very high mission generation rate. Its other less well-known task includes the medical evacuation of injured service personnel.

As far as the air-bridge into Afghanistan is concerned, the importance of the operation is often misunderstood. With overland routes into Afghanistan from various parts of Pakistan under almost daily attack from insurgents, the air-bridge has provided the only reliable way of resupplying the troops operating in theatre. The logistical support operation in Afghanistan mounted by the Royal Air Force and the United States Air Force has quite literally redefined the notion of airborne re-supply operations. The fleet of eight C-17 Galaxy aircraft operated by the RAF continues to perform an outstanding role supporting the members of the armed forces based in Afghanistan.