Lockheed C-130 Hercules (1954)

In the twenty-first century air power manifests itself in many different ways. It is not always about applying kinetic effect. There is also a dimension of reach. Air power can be applied at a strategic, operational and tactical level, but it is important not to immediately equate the notion of strategic effect to range. That has been a stereotype in the past that has gained traction among those writing doctrine. In the highly-connected world of the twenty-first century distance no longer has the same impact upon people. That translates into a public expectation that things can be done on a worldwide scale quickly.

In days gone by a need to fly humanitarian relief aid halfway round the world was a big issue. The payload that aircraft could fly was severely limited and there was always a question of where the nearest airfield to a disaster zone was located. Today military planners do not regard distance as a challenge.

This is the world where physical manoeuvre is less difficult than cognitive manoeuvre, where the aim is to secure support from the population. Strategic effect occurs where an action has an impact upon the world stage and other countries take notice. Mobilizing strategic airlift capability can be a very important way of projecting air power in what is seen as a beneficial way.

With the advent of the Boeing C-17 strategic heavy-lifting aircraft and its worldwide support network many of the past challenges of moving emergency freight over large distances have been addressed. Countries that operate the C-17 such as America, the United Kingdom, Qatar and Australia are able to work together to create an international heavy-lifting capability.

NATO has also purchased three C-17 aircraft, operating them from the Pápa airbase in Hungary. In July 2009 the first NATO supply mission involving one of those three aircraft was mounted into Afghanistan. The first three years of operations have proved so successful that in October 2012 NATO announced its desire to obtain additional C-17s for its fleet despite the imminent draw-down of its forces from Afghanistan. NATO clearly envisages that it will be conducting out-of-area operations in the future, but perhaps not in support of upstream interventions such as the deployment of its forces into Afghanistan.

In the case of responding to natural and man-made disasters this often sees ad hoc alliances of countries coming together to respond in the immediate aftermath of an event when the air agencies are simply overwhelmed. The scale of the disaster is often framed through the lens of the media. In response to the scale of the humanitarian disaster in Haiti in the wake of the earthquake in 2010 NATO deployed its C-17 fleet on their first humanitarian relief operation in February. This was the first time the NATO airbase at Pápa had been used as a logistics hub for relief supplies. Supplies from Sweden, Estonia and Bulgaria were flown first into Hungary before being loaded onto the NATO C-17. Three support missions carrying relief supplies were mounted into Haiti.

When disasters strike, through the careful choice of words and images reporters can quite literally mobilize public support at home. Pressure builds for governments to act and help those in need. Where governments are seen to be slow to act public opinion and donations to various charities can compel political action.

Today once that pressure builds any government that is unable to respond quickly becomes rapidly labelled as being unresponsive. That is a label that can easily stick as President George W. Bush found out in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. While the situation in New Orleans deteriorated rapidly the inaction in Washington led to the perception that the leadership simply did not care.

This is where the military’s ability to swiftly mobilize its resources to deliver medical supplies and other vital equipment to a place in the world in desperate need is a huge asset. It provides another insight into the application of air power and shows its ability to quickly mobilize urgent supplies over global distances in short periods of time. This is one that sometimes stereotypes of its use fail to fully appreciate. To explore this application of strategic and tactical airlift in greater detail a number of case studies are analysed from a range of viewpoints.

The Balkans

The conflicts in the Balkans in the 1990s provided an early portend of what was to follow once the stability of the Cold War had passed into history. In the Balkans old rivalries and ethnic tensions that had not been buried into the sands of time found new expression as the former Yugoslavia broke up into warring factions.

Throughout the mayhem of the conflicts whose axis seemed to shift almost on a daily basis some isolated communities got caught up as ethnic islands (or enclaves) in what was a sea of tensions and retribution. Local geography and highly variable weather conditions made maintaining supplies to these areas extraordinarily difficult. Of all the documented instances that emerged from the long series of wars in the region the siege of Sarajevo is one that is not readily forgotten. It still provides an important case study for future military commanders to examine.

When the last pallet of flour was carried away from a C-130 to a warehouse in Sarajevo airport on 13 February 1996 the longest-ever airlift operated in the world came to an end. The mission had commenced on 3 July 1992. It lasted for 1,321 days; far surpassing any other airlift recorded in history. It had run almost continuously over that period; only being suspended for a short time in 1993 when the aircraft were diverted to drop 20,000 metric tons of relief supplies into eastern Bosnia.

Operation Provide Promise had delivered 179,910 tons of food to Sarajevo in the course of 12,895 missions. On average ten flights a day brought 136 tons of relief supplies into Sarajevo. Most of the airlift capacity that achieved this feat was undertaken by five partners. USAF undertook 4,597 missions. Behind them their NATO allies Canada (1,860), France (2,133), Germany (1,279) and the United Kingdom (1,902) carried out the majority of the remaining missions.

Many of these involved flights into and out of Sarajevo under the threat of attack from ground fire and surface-to-air missiles. Many of the missions involved tactical transport aircraft such as the ubiquitous C-130. On one well-reported occasion twelve bullets destroyed the windscreen of a C-130 as it was attempting to land at the airport. For the crew on board that day, they had a lucky escape.

Fortunately, being fired upon when delivering humanitarian aid is a rarity. This also highlights an important point. Some missions flown into these operating environments have to be undertaken by military teams. The threat environment demands it. In permissive environments the role played by civilian cargo-carrying aircraft can be really important.

Worldwide Airlift

Across the world air forces are conscious of the need to play their part in delivering humanitarian relief to people in difficulties as a result of natural or man-made disasters. When Saddam Hussein turned on the Kurdish people, enclaves were established to try to protect them from his military forces. No-fly zones were created in which Iraqi airplanes would be engaged and shot down if they tried to attack the Kurdish people who were fighting for a separate homeland to respect their rights as an ethnic group. In the early stages of that campaign strategic heavy-lifting aircraft from the USAF were used to drop supplies to the people when a humanitarian disaster loomed.

In the immediate aftermath of the fighting that saw the Northern Alliance break out from their enclave in North Afghanistan and march on Kabul in the early part of 2002, a similar set of air-drop missions was conducted. This was all part of a plan to try to secure the hearts and minds of the local population.

When natural disasters strike air power is also readily mobilized to help bring in urgently needed food supplies and aid to people who are often in a desperate situation. In the wake of the tsunami that affected Japan and threatened a major environmental disaster as engineers fought for control of the Fukushima nuclear plant it was to strategic air power that the USAF turned to ensure that the urgent requests for help from the Japanese government did not go unanswered. With aircraft like the Boeing C-17 USAF was able to change its flying programme to accommodate the need to fly specialized fire-fighting equipment and other supplies into the disaster area.

Another tsunami that struck communities in the Pacific Ocean on 29 September 2009 saw USAF crews from Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii fly eleven C-17 aircraft loaded with 157 passengers and 378.3 short tons of cargo to American Samoa which had been struck by 15-ft waves. The aircraft carried cargo vans, trailers, water, medical supplies and ready-to-eat meals. The speed of response was helped by the close proximity of the C-17 aircraft to the area affected by the disaster. Two civilian airliners were also used in the relief operations.

Other examples also exist where air power has been rapidly mobilized in the wake of a major natural disaster. In 2005 as the drama of Hurricane Katrina played out across the world’s media an international relief effort was mobilized. Hurricane Katrina was the worst of its kind. The cost of damage exceeded $100 billion. This was four times the scale of any previous major natural disaster that had affected the United States. The response of the Bush Administration was slow and uncertain. The scale of the disaster seemed to overwhelm the authorities.

India, a country familiar with many disasters of its own, dispatched an IL-76 transport aircraft to deliver 25 tonnes of relief aid. Initially aid from Russia and France was politely turned down by the Bush Administration. Once the scale of the disaster became apparent those offers were quickly accepted. Even countries such as Sri Lanka, still recovering from the tsunami, offered help. When natural disaster strikes it appears the world community, no matter what their ethnicity or culture, is prepared to help.

After the terrible disaster in Haiti in January 2010 air power was at the focal point of the international community’s response. The earthquake which had measured 7 on the Richter scale claimed over 300,000 lives. Some 250,000 houses and over 30,000 commercial buildings were also destroyed, making over 1 million people homeless.

Across the world military and civilian aircraft were mobilized to move aid into Haiti. In this case such was the scale of the disaster that the ability to handle the arrival of the aid became an immediate problem. Electrical supplies, communications equipment and other basic services and infrastructure had all been destroyed. Air power was available but the rate at which aircraft would arrive in the country was slowed by the lack of rudimentary air-traffic control systems.

For a while the international response went into meltdown. Once military expertise was applied to the problem, things improved. For some of the seriously injured people the destruction of hospitals in Haiti meant that evacuation to America was the only way in which their lives could be saved. Even then political issues arose as hospitals in Miami became swiftly overcrowded. Similar tales arise from other major disasters. When there is an immediate need to deliver relief supplies air power’s unique qualities come to the fore.

The response of USAF to that sudden and unexpected disaster highlights one of the enduring qualities of air power. This is its ability to be versatile and flexible. In the United Kingdom the RAF shows similar qualities. The build-up of the RAF C-17 fleet from an initial leasing arrangement for four aircraft to a contract which saw a bigger fleet of eight mobilized provides a testament to the versatility of the platform.

Its range and payload capabilities are impressive and it has allowed RAF air-crews to mix the routine operations of the air-bridge into Afghanistan with some more diverse missions into places such as Pakistan, Columbia and Benghazi carrying disaster relief supplies to the first two countries and large amounts of cash into Libya to help maintain the viability of the banking system.

Air power can be applied in so many different ways to achieve effects. One other important mission, both for the RAF and USAF, is the return of injured personnel from theatre to specialized hospitals in the United Kingdom and the United States. Possibly the most difficult of all the missions flown by the C-17 are those that repatriate the bodies of servicemen killed in action. Those are very sombre affairs.

Boeing C-17

The cost of aircraft like the C-17 means that very few countries can afford to buy and operate their own fleets which can then be deployed in times of crisis. NATO has come up with one model where three C-17 aircraft have been bought as a result of twelve countries pooling resources. Ten members of NATO and two partner countries (Sweden and Finland) agreed to come together to purchase a strategic heavy-lifting capability that would be based in Hungary.

The first aircraft arrived in July 2009. By October all three aircraft had been delivered to their operating base at Pápa Air Base. In deciding where the air wing was to be located those involved had carefully looked at the potential expansion of the facility at the airbase and its geo-strategic location. Planners envisage that in time the airbase could become a strategic hub for humanitarian relief operations.

This relatively new capability was mobilized in January 2010 to provide assistance to the victims of the Haiti earthquake. On the third flight into Haiti NATO’s Heavy Airlift Wing flew supplies and equipment donated by Estonia, Finland and Sweden to supply and construct a camp for aid workers at the airport at Port-au-Prince.

Berlin Airlift 1948

Of all the applications of tactical and strategic heavy-lifting capability the Berlin Airlift stands out as the leading example. As the Second World War had come to its inevitable conclusion once the German attack on Russia had so spectacularly failed, the race had been on between the Allies and the Russians to capture Berlin.

That was won by the Russians. However, because of the significance of Berlin as a political centre in Germany it was agreed that despite it being well inside what was now de facto occupied Russia, the city would be divided into four zones. These would be administered by the Russians, United States, France and the United Kingdom. At the time when the city was partitioned an agreement was signed that provided for road and rail links through the Russian-occupied territories to bring supplies into the city. To assert Soviet authority over the links they were subjected to periodic interruption. On 1 April 1948 the Soviets applied new rules over the movement of supplies by rail. No cargo was allowed to leave Berlin without permission of the Soviet commander in the city.

This caused the Americans to start a small airlift to supply their own forces in the city. This was nicknamed the ‘little lift’. The Soviets responded, flying fighter jets to confront the transport aircraft. Sometimes this was deadly serious. One incident occurred as a result of direct harassment by a Soviet Yakolev Yak-3 fighter which collided with a British civilian aircraft on 5 April 1948. All of the people on both aircraft died. In total throughout the crisis USAF reports published at the time suggest that the Americans complained of interference in the flights on nearly 750 occasions. It seems in hindsight that this figure was probably an exaggeration.

Eventually the continued disruption of these links precipitated the crisis. It also stopped the 13,500 tons of food a day that routinely flowed into Berlin. Only the air corridors that were protected by an internationally-recognized treaty remained open.

From 24 June 1948 to 12 May 1949, a period of nearly a year, the combined efforts of the Allied air forces sustained a city under siege flying over 92 million miles in the process. This is almost the same distance as from the Earth to the sun. In the course of the airlift the Allies maintained air supplies to a population of just over 2 million people. In the early part of the response as the numbers of aircraft available were steadily ramped up, one flight took off every three minutes. That separation was maintained throughout the 270-km flight. It was like a conveyor belt of food in the sky.

The initial force of 100 C-47 ‘Gooney Bird’ aircraft were just able to move enough supplies into Berlin to support United States forces based in the city. General Curtis LeMay who then commanded USAF in Europe was able to fine-tune this delivery a little, but he knew that to try to achieve the wider objective of feeding the population as a whole he would need additional aircraft.

To supplement the initial effort C-54 Skymasters were made available. They could carry a payload of 10 tons which was four times the capacity of the C-47. By the end of August 1948 225 C-54s were dedicated to the airlift. This was 40 per cent of the USAF total fleet.

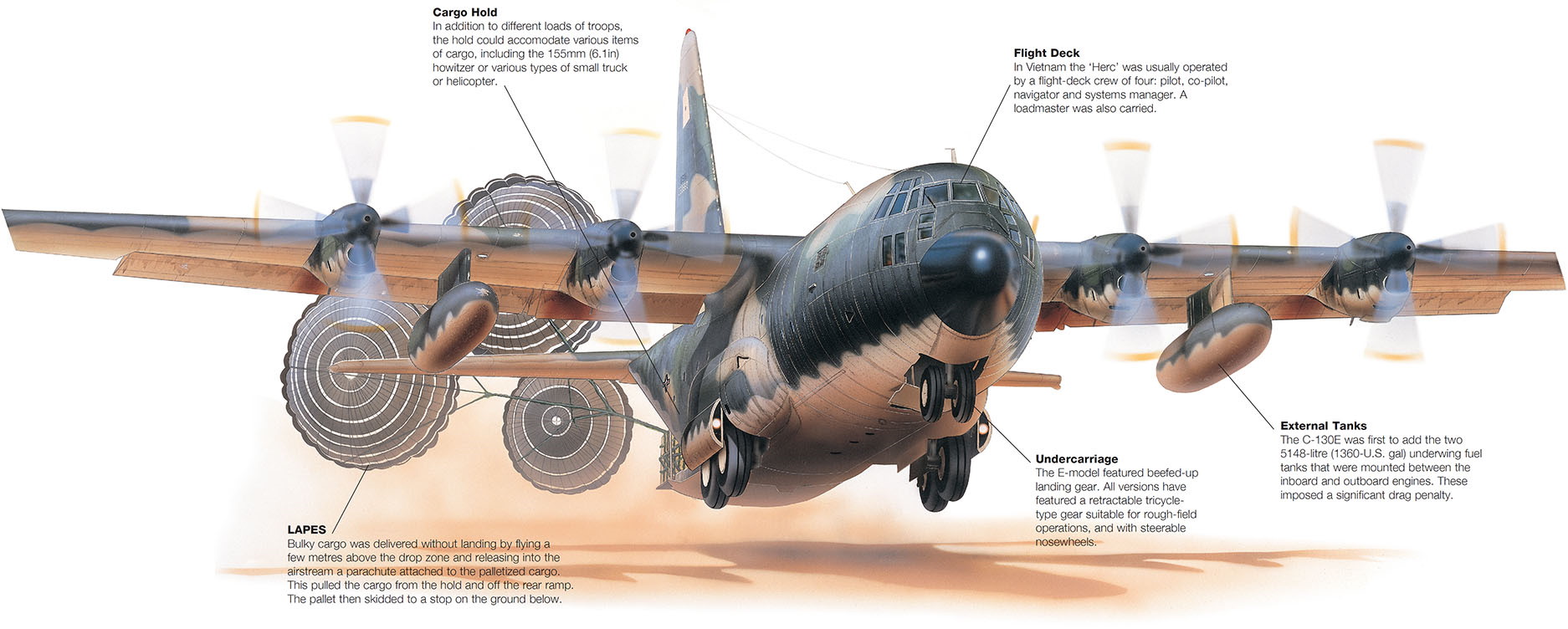

By today’s standards these are quite small loads. The C-130 tactical transport aircraft (Hercules) can carry a payload of 19 tons. The C-17 can carry up to 85 tons and the C-141 is able to lift 34 tons. The USAF C-5 can lift 145 tons. The air speeds are also appreciably faster. Had the Berlin Airlift to be repeated today, the same effect could be achieved with sixty C-17 flights per day.

In the course of the crisis 2.3 million tons of cargo had been moved into Berlin in nearly 280,000 flights; an average close to 1,000 a day. This is an average lift of 8.3 tons per flight. That meant that at least 600 flights a day had to land in Berlin to sustain the food flow. By contrast the lengthy effort to sustain the people of Sarajevo lifted about 8 per cent of the total supplies moved into Berlin.

The flight pattern was organized with military efficiency. Aircraft occupied five different flight levels separated by 500ft from a lowest level of 5,000ft. At each flight level aircraft were maintained at a distance of fifteen minutes’ flight time. The net effect was to create a three-minute gap between each aircraft arriving in Berlin at the start of the operation.

Given that there are only 1,440 minutes in a day and at the start of the airlift aircraft were only landing once every three minutes, it is possible to see just how far the original effort ramped up. It also cost seventeen American and eight British planes that were lost due to crashes. This cost 101 airmen their lives, including forty Britons and thirty-one Americans. The total cost of the operation was put at just over $220 million. This is the equivalent of just over $2 billion today. Final figures show that the RAF carried nearly 550,000 tons of supplies and USAF 1,750,000 tons. The Royal Australian Air Force also delivered nearly 8,000 tons of freight and 7,000 passengers in just over 2,000 sorties.

To feed and keep warm the people of Berlin the initial estimates suggested that up to 5,000 tons of food and heating supplies would be needed to be flown into Berlin every day. This split as around 1,500 tons of food and 3,500 tons of coal and gasoline. The first calculations undertaken as the crisis deepened suggested that 2,000 tons a day was the bare minimum. This of course was a very low estimate.

In the course of the winter period this grew by an additional 6,000 tons a day. Coal was the most difficult substance to move into Berlin. It amounted to 65 per cent of the cargo carried into the city. Its dust got everywhere and helped corrode cables and flight controls. Crews also complained of breathing difficulties.

The American name for the airlift was Operation Vittles. The United Kingdom called it Operation Plainfare. At its peak one aircraft was arriving in Berlin every thirty seconds. Each captain was only allowed a single approach. If they missed the landing they went back to the airbase from which they had launched their sortie. It was quite simply an extraordinary achievement.

The crisis had blown up over a period of time as the Soviet Union tried to apply pressure on the west. Rail and motorway supplies into Berlin had been disrupted on some occasions previously as tensions waxed and waned, but to try to force the situation where Berlin became integrated into the Soviet Union these routes were suddenly cut off. The population of Berlin was being held to ransom. Soviet offers of free food for those that crossed the border in the city into the zones not controlled by the Allies were rebuffed by the population. Attempts to rig elections were also similarly defeated.

Throughout the crisis the Berliners maintained a steadfast approach. During the winter months fog proved to be a huge challenge. On 20 November forty-two aircraft had set out to fly into Berlin and only one aircraft landed. At one point the amount of coal left in the city was down to a level that could only sustain it for a week. With an improvement in the weather over 171,000 tons of food and fuel was supplied in January 1949. In February that fell back to 152,000 tons before increasing again in March to 196,000 tons. As the crisis came to a close the Allies mounted a huge effort over the Easter period. This became known as the ‘Easter Parade’. On 16 April 1949 1,398 flights brought in 12,940 tons of supplies. At this point aircraft were arriving into Berlin at one every minute.

By this time the Soviets began to realize that the Allied effort had been sustained through the winter and that with the arrival of the spring and summer months a backlog of supplies could be built up ahead of the next winter. Soon after this point negotiations started to bring an end to the crisis. The west had been able to stop Berlin falling into the hands of the Soviet Union. It was now at that last moment that the Allies and the Soviet Union had a stand-off over Berlin. In 1961 another crisis blew up as the west confronted the Soviet Union over the future of Berlin.