The Panzer Thrust to Capture Moscow October-November 1941

JAMES LUCAS

Introduction

By the Autumn of 1940, the nations of Europe’s western seaboard had been defeated by Germany, leaving only the British Isles unconquered and defiant, although weak. Knowing that Britain posed no real threat Hitler decided to wage war against the Soviet Union on the pretext that the eastern provinces of Germany had to be beyond the range of Red Air Force bombers. When that war was concluded and the Reich held an area of western Russia running from the Volga to Archangel, not only would eastern Germany be safe from air attack, but Russia’s bread basket, the Ukraine, would be within the German cordon sanitaire as would the Don basin’s industrial complexes. The remnant of the defeated Red Army would be on the eastern side of the Volga and Germany’s supremacy would be unchallengeable.

In September, Hitler briefed the leaders of the German Armed Forces and of the Army High Command (OKW and OKH). Those officers must have been surprised that the Führer did not name a point of maximum effort or Schwerpunkt, the strategic objective to be gained. Instead he named three targets, allocating one to each of the Army Groups which were to fight the war: Leningrad for Army Group North, the Ukraine for Army Group South, and for Army Group Center, Moscow—but only after the northern and southern goals had been gained. Hitler declared Moscow to be a geographical term with no military significance. His decision broke with the German Army’s basic precept that Field armies march separately but strike together. In Russia his Army Groups would march separately and would also strike separately. Such a policy might have been a recipe for disaster but, by a fateful paradox, the flawed strategy of the command hierarchy of the Red Army, the Supreme Stavka, saved Hitler from the consequences of this dilettante folly.

On 22 June 1941, the German armed forces attacked the Soviet Union. The opening operations were everywhere successful and the course of the campaign in the first months was marked by the encirclement of huge numbers of Red Army formations by fast-moving panzer forces. The scale of the Soviet losses in those first encirclements, together with the far greater casualties inflicted in the encirclements that followed in quick succession, convinced the German High Command that the Red Army had been defeated west of the Dnieper, as Hitler had planned. If there was any doubt felt at OKH it was that the advance of Germany’s armies was still being contested, and by previously unidentified Soviet military formations. These were, undeniably, fresh troops but were discounted by the High Command as Stalin’s last reserves. The war on the Eastern Front was as good as over.

The Führer Designs a Revolutionary Battle Plan

During the middle week of August 1941, OKH sent Hitler a memorandum urging that the German Army’s principal aim should be the capture of Moscow by Army Group Center. The Führer rejected that recommendation. He was working on Operation WOTAN, a revolutionary offensive, and saw from the dispositions on the map of the Eastern Front the strategy he would follow. Soviet main strength was concentrated to the west of the capital and could be easily reinforced, making frontal attacks to capture the city from the west both costly and time-consuming. The Führer recalled that during the Great War it became standard practice to infiltrate round the enemy’s flanks in order to attack an objective from the rear. His revolutionary battle plan would do just that. Faced by a strong defense west of Moscow he would withdraw the four Panzer Groups serving on the Eastern Front and concentrate them into a single Panzer Army Group. This he would unleash and send marching below Moscow and on an easterly bearing. At Tula it would change direction and thrust north-eastwards across the land bridge between the Don and Volga rivers before taking a new line and driving northwards to capture Gorki, some 400km east of the capital. After a short pause for regrouping, a coordinated attack by Army Group Center from the west and Panzer Army Group from the east would capture Moscow

Stavka would certainly react violently when the panzer hosts thundered across the steppes but the Führer would limit their ability to counter WOTAN. He would launch massive offensives using the infantry armies on the strength of the three Army Groups. These would tie down the Red armies and prevent Stavka from moving forces to challenge Panzer Army Group’s thundering charge.

The longer the Führer looked at the map the more confident he became that his plan could take Moscow well before winter. He knew that the terrain of the land bridge between the Don and Volga rivers was good going for armor. The roads in the area were few and poor but the General Staff handbook considered that the sandy soil of the land bridge allowed movement even by wheeled vehicles off main roads and across country. The one caveat was that short periods of wet weather could make off-road movement difficult and longer spells could make the terrain impassable. The presence of so many rivers might slow the pace of the advance but that difficulty could be overcome by augmenting the establishment of panzer bridging companies with extra pioneer units. A revolutionary battle plan demands a revolutionary supply system and Hitler was convinced that he had found one. Isolated even from his closest staff members he worked on the final details of Operation WOTAN.

Kesselring Becomes Commander of the Panzer Army Group

A telex sent on the morning of 23 August brought Field Marshal Kesselring to Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters. The commander of Second Air Fleet supposed he had been summoned to brief the Führer on the progress of air operations on the central sector, but Hitler’s first words astonished him.

“I have decided to mount an all-out offensive for which all four Panzer Groups on the Eastern Front will be concentrated into a huge armored fist—a Panzer Army Group. This you will command.”

To Kesselring’s protests that he was no expert in armored warfare the Führer replied that he did not want one. Such men were always too far forward and out of touch—Rommel in the desert was a typical example of the panzer commander. No, he needed an efficient administrator and he, Kesselring, was the best in the German Services.

The Luftwaffe commander then asked how the Panzer Army Group was to be supplied and was told “by air-bridge.” The entire strength of the Luftwaffe’s Ju-52 transport fleet, all 800 machines, would be committed, and each machine would not only carry two tons of fuel, ammunition or food but would also tow a DFS glider loaded with a further ton of supplies. Thus 2400 tons would be flown in in a single “lift.” Hitler maintained that each flight would be so short that the Ju pilots could fly three missions in the course of a single day and this would raise the total of supplies to 7200 tons daily; more than enough to nourish the Panzer Army Group in its advance.

“There will be losses. Aircraft will crash, others will be shot down …”

“And those losses will be made good.”

Hitler then went on to explain that in the event of a sudden emergency requiring even more supplies, every motor-powered Luftwaffe machine would be put into service as would also the giant gliders which had been built for the invasion of Britain. Supplies would be dropped by parachute or air-landed from the Ju transports. Hitler’s remarkable memory recalled that ammunition boxes could be thrown from slow-flying transports at a height of four meters without damage but warned Kesselring that there was a high breakage rate—one in five—among the 250 liter petrol containers, unless these were specially packed. Once the panzer advance was rolling the Ju’s would no longer need to para-drop or air-drop the supplies but would land and take off from the salient which the Panzer Army Group had created. As the salient area expanded lorried convoys would be re-introduced. Aware of the vast amount of fuel that would be needed for the forthcoming operation, Kesselring asked what Germany’s strategic fuel reserves were and was told that these were sufficient for two to three months, including the requirements of WOTAN.

Hitler’s hands, moving across the map on the table, demonstrated where the break-through would occur and then illustrated the drive towards Gorki. The momentum of the attack must be maintained by a pragmatic approach to problems and Kesselring was to ensure the closest liaison between the flight-controllers of both Services so that the pilots had no difficulty in finding the landing zones. It was the duty of the Luftwaffe to give total support to the Army by dominating the skies above the battlefield and ensuring that the ground units were protected from attack at all times.

Hitler assured the Luftwaffe commander that the weather forecast was for hot, sunny weather which meant that ground conditions would be excellent. Operation WOTAN should last no more than eight weeks so that the offensive would be in its last stages before the onset of the autumn rains, and would be concluded before winter set in. Long-range meteorological forecasts predicted that the present dry weather would continue until late in October.

The Führer explained that Supreme Stavka had moved the bulk of its forces to counter the blow which they anticipated would be made by von Rundstedt’s Army Group South.

“We shall fox Stavka by maintaining pressure in the south but using mainly infantry forces. Stalin will have to reinforce that sector, whereupon Army Groups North and Center will each open a strong offensive. While the Soviets are rushing troops from one flank to another your Panzer Army Group will open Operation WOTAN, will fight its way through the crust of Red Army Divisions and reach the open hinterland. From there the exploitation phase of the battle will begin and from that point you should encounter diminishing opposition. Of course, your advance will be contested but the presence of so great a force of armor behind the left flank of Westfront will unsettle the enemy. But the Russians, both at troop and at Supreme Command level, react slowly … so make ground quickly before they realize the danger you represent.”

Hitler then declared that once he had briefed the other senior commanders, planning for WOTAN could begin. Because the individual Panzer Groups were at present committed to battle they could not be withdrawn and concentrated in toto. X-Day for each Panzer Group would depend upon how quickly it could be removed and regrouped but he thought that they should all be ready to begin WOTAN by 9 September. In answer to Kesselring’s concern that the infantry armies would bear the brunt of battle without panzer support Hitler stressed that a number of armored battalions and, possibly, some independent regiments would still be with the three Army Groups. He did agree that those panzer formations would have to act as “firemen,” rushing from one threatened sector to another.

In farewell, Hitler grasped Kesselring’s hands in his own, gave him the piercing look mentioned by so many of those who met the Führer and told him that Operation WOTAN offered the armies in the East the chance of total victory within a few months, but only if each officer and man was prepared to give of his utmost for the duration of the offensive. National Socialist fanaticism, the Führer concluded, would produce the victory that was within the Field Marshal’s grasp.

“Remember, Kesselring. The last battalion will decide the issue.”

On 24 August, in the Warsaw headquarters of Second Air Fleet, Kesselring addressed the leaders of the formations he was to command and told them that for the opening assault Panzer Groups Guderian, Hoth and Hoepner were to attack shoulder to shoulder in order to create the widest possible breach. That break-through would be succeeded by the pursuit and exploitation phase which would produce a salient running up to Gorki.

“To create that salient,” said Kesselring, “Guderian and Hoth will form the assault wave, Hoepner and Kleist will line the salient walls, and in addition to that task will also defeat enemy attacks made against those walls and will replace losses suffered by the spearhead groups.”

“Each Division has Luftwaffe liaison officers but at Panzer Group and Panzer Army Group level there will be a Luftwaffe Signals Staff unit to ensure total success in the matter of locating and supplying your units.

“I need not tell you how to fight your battles. You have grown up with the blitzkrieg concept, so any words of mine would be superfluous. We know our tasks. Let us to them and achieve the Führer’s aim: victory in the East before winter.”

Hitler Briefs the OKH Staff

On Friday, 29 August, Hitler addressed the OKH staff. A summary of his briefing reads:

“The successes of the three Army groups now make Moscow the principal objective … Operation WOTAN will open on 9 September and will consist of separate offensives by the infantry Armies of each Army Group as well as by a Panzer Army Group working towards the capture of the Soviet capital … The Panzer Groups will concentrate into the Panzer Army Group as they conclude present operations …

“Speed is vital … no pitched battles … strong enemy resistance is to be bypassed and left to the infantry and the Stukas to overcome. Panzer Divisions will consist of fighting echelons only … No second echelon soft-skin vehicle supply columns … Troops to live off the land as far as possible. Once the first issues of petrol, rations, ammunition and spares are run down, subsequent supplies will be air-landed or air-dropped. The infantry formations serving with the Panzer Groups will foot march unless the railways can be put into operation to ‘lift’ them.”

The first withdrawals to thin out the panzer formations so that WOTAN could open on 9 September were halted abruptly on the 8th, when the armies of Marshals Timoshenko and Budyenny opened “spoiling” offensives. These were incompetently handled and were defeated so thoroughly that only weeks later Budyenny’s South West Front had been destroyed around Kiev with a loss to the Russians of 665,000 prisoners. That defeat was followed by others at Vyasma and Briansk. The intensity of the fighting and the vast distances over which military operations were conducted during those encirclements tied up the Panzer Groups so completely that OKH’s intention to thin them out could not begin again until mid-September. As a result concentration could not be completed simultaneously by all the Groups, and each went into what had now become the second stage of WOTAN on various dates. Those Panzer Groups, urged on by a jubilant Hitler, were unrested, unconcentrated, under strength and driving vehicles that needed complete overhaul but each advanced towards its start lines. It was Friday, 28 September, and it was fine and sunny.

Operation WOTAN Begins

On X-Day Panzer Group 1 was in action on the southern side of the encircling ring around Kiev; Guderian’s Group 2, leaving XXXXVIII Corps at Priluki, had disengaged from the encirclement’s northern side and had concentrated around Glukhov; while Panzer Groups 3 and 4 were still deeply committed to the battles at Briansk and Vyasma. The long advance to battle which they would have to undertake meant that they would enter late into the second stage of WOTAN. Guderian, impatient to march, decided that if the other groups were not in position by X-Day then he would open the operation without them. His formations moved forward, and at dawn on the misty morning of 30 September, the order came: “Panzer marsch.” Guderian named as his Group’s first objective the road and rail communications center of Orel. General Geyr von Schweppenburg’s XXIV Panzer Corps, with 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions in the line, advanced up the Orel road, while Lemelsen’s XXXXVII Panzer Corps, fielding 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions, flooded across the lightly undulating terrain to the north of the highway.

Guderian’s soldiers were confident. On the eve of the offensive Heini Gross, serving in one of the panzer battalions of 4th Division, wrote “Last evening the Corps Commander visited us. There were several speeches and then we all sang the ‘Panzerlied.’ Very, very moving. Tomorrow at 05:30 we open the attack which will win the war.”

Guderian’s first blows smashed the left wing of Yeremenko’s Front and within a day had crushed Thirteenth Red Army. Soviet counterattacks launched by two Cavalry Divisions and two Tank Brigades were flung back in disarray by 4th Panzer Division. Through the gap which had been created XXIV Corps struck for Sevsk, captured it and drove on towards Orel while XXXXVII Corps swung north-eastwards for Karachev and Briansk. To the north of Guderian, von Weichs’ Second Infantry Army brought about the collapse of Yeremenko’s right wing when it split asunder the Forty-third and Fiftieth Red Armies. Within two days Panzer Group 2 had driven 130km through the Soviet battle line against minimal opposition. A breach had been made between Orel and Kursk and Kesselring directed the other Panzer Groups to reach and pass through “Guderian’s Gap,” in order to begin the exploitation phase of WOTAN. That order drove Kleist’s Panzer Group 1 northwards from the Kiev ring and was to send Groups 3 and 4 southwards once the main part of their forces had been withdrawn from the Vyasma encirclement battles.

On 2 October, the first air drop was made to Guderian’s Group. Friedrich Huber in a Flak battery recalled, “Fighter aircraft circled above us to drive off any Russian machines. Then the Ju-52s flew in, approaching from the west at a great height, descended lower and circled. They roared low above our heads, the yellow identification stripe [carried by aircraft on the Eastern Front] glowing in the sunlight. A cascade of boxes and the first flight climbed, circled and flew back westwards. In less than ten minutes forty Ju’s had supplied us. Another flight of forty came in, delivered and flew off to be followed by a third wave. This is an idea of the Führer, of course. Simple and effective, swift and efficient …”

Stavka’s reaction to the 2nd Panzer Group attack was sluggish and the weak tank attacks against XXIV Corps were repulsed with heavy loss. Guderian’s Group gained ground at such pace that it was confidently believed the hard crust of the Soviet defense must have been cracked. But it had not. Supreme Stavka ordered that Tula, on the southern approaches to Moscow, was to be held to the last, and the fanatical Soviet defense of the area between that city and Mtsensk brought the first check to 2nd Panzer Group’s drive.

Kesselring, who had been elated at the fall of Orel on 3 October, intended to capitalize on that success by changing WOTAN’s thrust line. Hitler had ordered this to be north-easterly: Dankov-Kasimov-Gorki. That original direction Kesselring now changed so that it marched northwards from Orel, via Mtsensk and Tula, to attack Moscow from due south.

Guderian’s Panzer Group Checked at Mtsensk

It was Colonel Katukov’s armor positioned south of Mtsensk that checked Guderian. A post-battle report, by the staff of XXIV Panzer Corps described the first two days of battle:

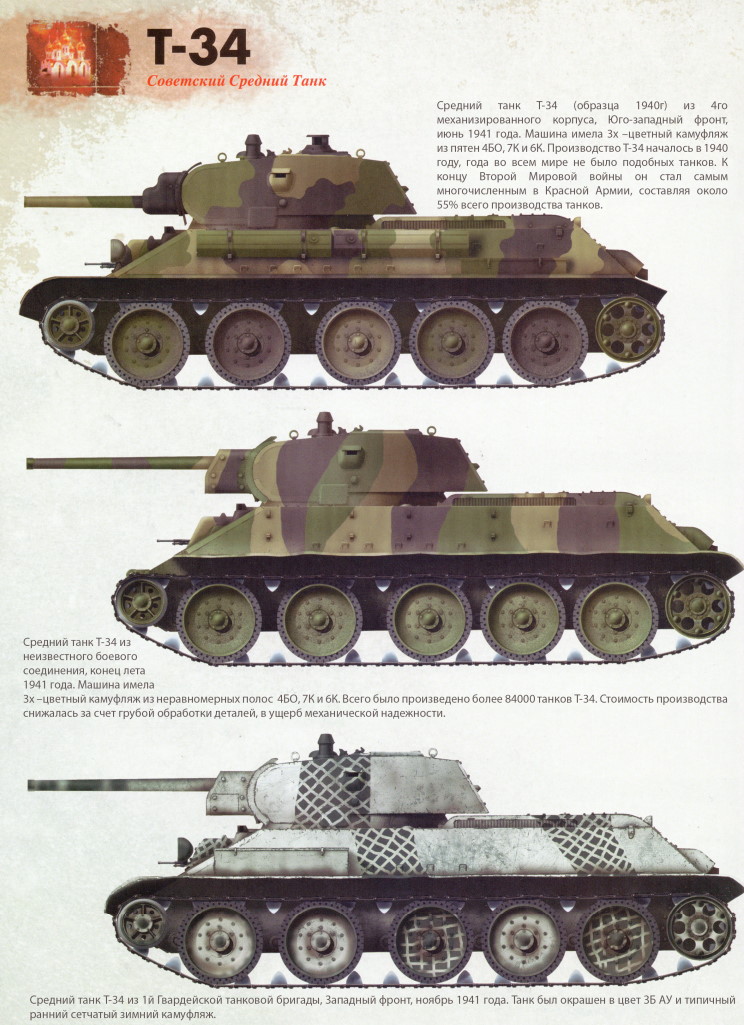

“The unit confronting us on the Tula road was 4th Tank Brigade equipped with T34s fresh from the factory. We had met this tank type before but never in such numbers. It is indisputable that the T-34 is superior to our panzers. We overcame them by calling for Stuka strikes and by setting up lines of our 88mm anti-aircraft guns and employing these in a ground role.”

Kesselring’s disobedience of Hitler’s order forbidding Panzer Army Group to become involved in pitched battles had resulted in Guderian’s drive faltering. To retrieve the situation OKH moved Second Infantry Army from 2nd Panzer Group’s left flank to its right and gave the infantry force the task of capturing Tula. Guderian’s Group, relieved on 7 October, then raced for its next objective, Yelets to the north-west of Voronezh and some 160km distant. Its advance was still unsupported. The other Panzer Groups had still not yet reached the breached area.

Hitler had correctly forecast that Stavka’s slow reaction to WOTAN would allow the Panzer Army Group to gain ground swiftly and Guderian met little organized opposition en route to Yelets. It was principally ill-trained local garrisons reinforced by untrained factory militias who came out to contest the German advance. Lacking adequate training they were slaughtered.

The crossing of the Olym river might have delayed Guderian more than the Russian enemy, but Hitler’s insistence upon extra pioneer units to accompany the Panzer Groups had proved him right and six tank-bearing bridges were erected in a single day. On 11 October Guderian’s reconnaissance detachments entered the outskirts of Yelets and quickly captured the town. The leading elements pressed on: the next water barrier was the mighty Don where Panzer Group 2 could expect to meet serious resistance unless the river could be “bounced.” For the Don crossing Guderian demanded the strongest Stuka support. His Divisions moved towards the river ready to cross on 14 October.

At dawn on that day the Stukas, the Black Hussars of the air, flew over the battle area and systematically destroyed everything which moved on the Don’s eastern bank. Yelets came within the defense zone of Voronezh and was ringed by deep field fortifications and extensive mine fields. “We attacked under cover of a smoke screen across a vast, flat and open piece of ground towards the Don,” explained Hauptmann Heinrich Auer. “On our sector the bluffs were over 100 meters high but upstream where they were almost at water level the Pioneers constructed bridges. We motorized infantry crossed in assault boats, then scaled the bluffs to storm the bunkers and trenches. The Stukas had bombed the Ivans so thoroughly that they were ready to surrender …

“It is not true that the crossing was easy. It was not but at its end we had broken the Don river line. Our panzers crossed the first bridge at about 1400hrs and came up to support us. Together we fought all that night and most of the next day. By the afternoon of the 15th we had reached the confluence of the Don and the Sosna, to the west of Lipetsk, and dug in there. The panzers left us at that point and wheeled north towards Lebyedan …”