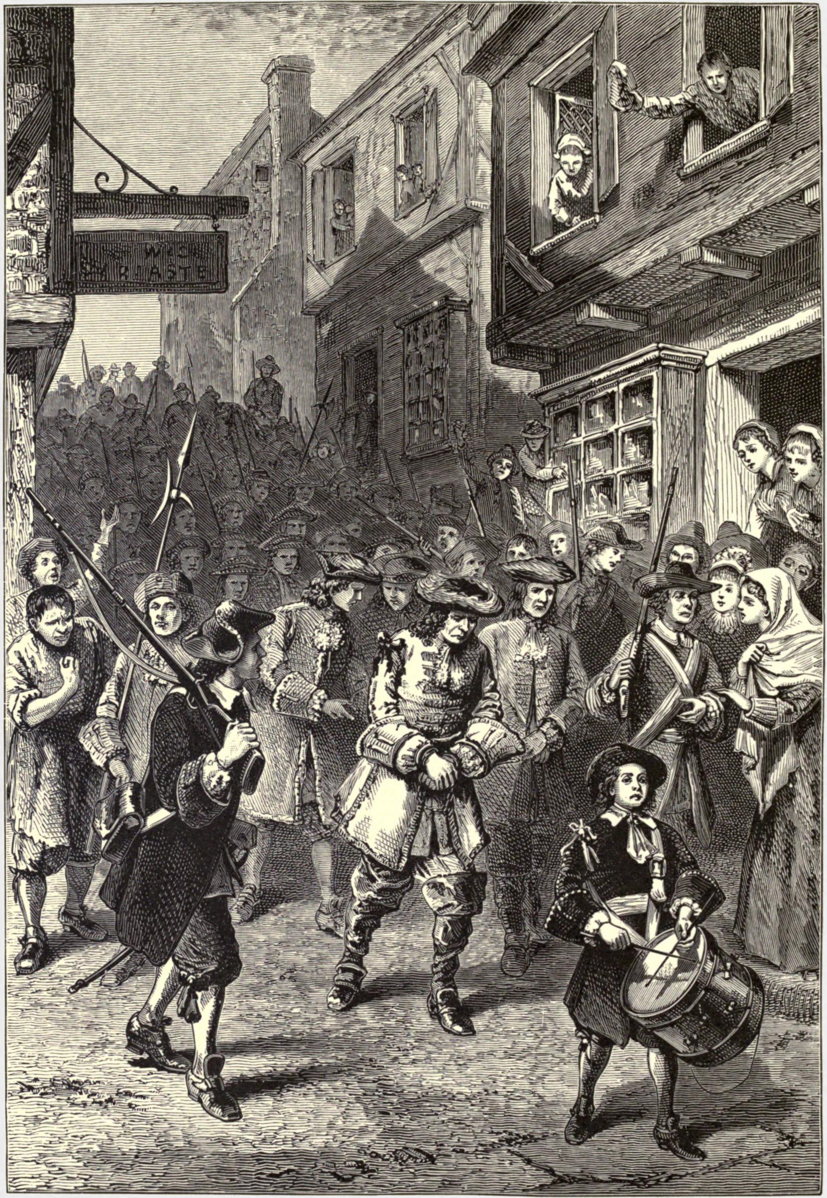

Andros a Prisoner in Boston

While everyone knows that the English-controlled colonies rebelled against the tyrannical rule of their distant king, few realize they first did so not in the 1770s, but in the 1680s. And they did so not as a united force of Americans eager to create a new nation, but in a series of separate rebellions, each seeking to preserve a distinct regional culture, political system, and religious tradition threatened by the distant seat of empire.

These threats came in the form of the new king, James II, who ascended the throne in 1685. James was intent on imposing discipline and political conformity on his unruly American colonies. Inspired by the absolutist monarchy of France’s Louis XIV, King James planned to merge the colonies, dissolve their representative assemblies, impose crippling taxes, and install military authorities in the governors’ chairs to ensure that his will was obeyed. Had he succeeded, the nascent American nations might have lost much of their individual distinctiveness, converging over time into a more homogeneous and docile colonial society, resembling that of New Zealand.

But even at this early stage of their development—only two to three generations after their creation—the American nations were willing to take up arms and commit treason to protect their unique cultures.

James wasted little time executing his plans. He ordered the New England colonies, New York, and New Jersey to be merged into a single authoritarian megacolony called the Dominion of New England. The Dominion replaced representative assemblies and regular town meetings with an all-powerful royal governor backed by imperial troops. Across Yankeedom, Puritan property titles were declared null and void, forcing landowners to buy new ones from the crown and to pay feudal rents to the king in perpetuity. The Dominion governor seized portions of the town commons in Cambridge, Lynn, and other Massachusetts towns and gave the valuable plots to his friends. The king also imposed exorbitant duties on Tidewater tobacco and the sugar produced around the recently formed settlement of Charleston. All of this was done without the consent of the governed, in violation of the rights granted all Englishmen under the Magna Carta. When a Puritan minister protested, he was tossed in jail by a newly appointed Dominion judge, who told him that his people now had “no more privileges left . . . [other] than not to be sold for slaves.” Under James the rights of Englishmen stopped at the shores of England itself. In the colonies the king would do whatever he wished.

Whatever their grievances, the colonies probably would not have dared revolt against the king had there not also been serious resistance to his rule back in England. At a time when Europe’s religious wars were still in living memory, James had horrified many of his countrymen by converting to Catholicism, appointing numerous Catholics to public office, and allowing Catholics and followers of other faiths to worship freely. England’s Protestant majority feared a papal plot, and between 1685 and 1688 three domestic rebellions erupted against James’s rule. The first two were put down by royal armies, but the third succeeded through a strategic innovation; instead of taking up arms themselves, the plotters invited the military leader of the Netherlands to do so for them. Invading from the sea, William of Orange was welcomed by a number of high officials and even James’s own daughter, Princess Anne. (Supporting a foreign invader against one’s own father may seem a bit odd, but William, in fact, was James’s nephew and was married to his daughter Mary.) Outmaneuvered by friends and family alike, James fled into exile in France in December 1688. William and Mary were crowned king and queen, ending a bloodless coup Englishmen dubbed the “Glorious Revolution.”

Because it took months for news of the coup to reach the colonies, rumors of a planned Dutch invasion continued to swirl there throughout the winter and early spring of 1689, confronting the colonials with a difficult choice. The prudent course would have been to wait patiently for confirmation of how events in England had played out. A bolder alternative was to defend their societies by rising up against their oppressors in the hopes that William actually had invaded England, that he would be successful, and, if so, that he would look kindly on their actions. Each of the American nations made its own choice, for its own reasons. In the end, the only ones not to opt for rebellion were the young colonies around Philadelphia and Charleston, which, with just a few hundred settlers each, were in no position to engage in geopolitics even if they wanted to. But many people in Yankeedom, Tidewater, and New Netherland were ready and willing to risk everything for their respective ways of life.

Not surprisingly, Yankeedom led the way.

With their deep commitment to self-government, local control, and Puritan religious values, New Englanders had the most to lose from King James’s policies. The Dominion governor, Sir Edmund Andros, lived in Boston and was particularly eager to bring New England to heel. Within hours of stepping off the boat in Massachusetts, the governor had issued a decree that struck at the heart of New England identity: he ordered Puritan meetinghouses opened for Anglican services and took away the New Englanders’ charters of government—which the people of Boston described as “the hedge which kept us from the wild beasts of the field.” Anglicans and suspected Catholics were appointed to top government and militia positions, backed by uncouth royal troops who witnesses said “began to teach New England to drab, drink, blasphemy, curse, and damn.” Towns were forbidden to use taxpayer funds to support their Puritan ministers. In court, Puritans faced Anglican juries and were forced to kiss the Bible when swearing their oaths (an “idolatrous” Anglican practice) instead of raising their right hand, as was Puritan custom. Liberty of conscience was to be tolerated, Andros ordered, even as he built a new Anglican chapel in what had been Boston’s public burial ground. A people who believed they had a special covenant with God were losing the instruments with which they had executed his will.

The Dominion’s policies, the inhabitants of Boston concluded, had to be part of a “Popish plot.” Their “country,” they would later explain, was “New England,” a place “so remarkable for the true profession and pure exercise of the Protestant religion” that it had attracted the attention of “the great Scarlet Whore” who sought “to crush and break” it, exposing its people “to the miseries of utter exploitation.” God’s chosen people could not allow this to happen.

In December 1686 a farmer in Topsfield, Massachusetts, incited his neighbors into what was later described as a “riotous muster” of the town militia, in which they pledged allegiance to New England’s old government. Neighboring towns, meanwhile, refused to appoint tax collectors. Governor Andros had the agitators arrested and fined. The Massachusetts elite defied Andros’s authority by secretly dispatching theologian Increase Mather across the Atlantic to make a personal appeal to King James. In London, Mather warned the monarch that “if a foreign prince or state should . . . send a frigate to New England and promise to protect [us] as under [our] former government, it would be an unconquerable temptation.” Mather’s threat to abandon the empire did not move James to change his policies. Yankeedom, Mather reported after his royal audience, was to be left in “a bleeding state.”

When rumors of William’s invasion of England reached New England in February 1689, Dominion authorities did their best to stop them from spreading, arresting travelers for “bringing traitorous and treasonable libels” into the land. This only fueled Yankee paranoia about a Popish plot, now imagined to include an invasion by New France and its Indian allies. “It is high time we should be better guarded,” the Massachusetts elite reasoned, “than we are like to be while the government remains in the hands by which it hath been held of late.”

The Yankee response was swift, surprising, and backed by nearly everyone. On the morning of April 18, 1689, conspirators raised a flag atop the tall mast on Boston’s Beacon Hill, signaling that the revolt was to begin. Townspeople ambushed Captain John George, commander of HMS Rose, the Royal Navy frigate assigned to guard the city, and took him into custody. A company of fifty armed militiamen escorted a delegation of pre-Dominion officials up the city’s main street and seized control of the State House. Hundreds of other militiamen seized Dominion officials and functionaries, placing them in the town jail. By midafternoon, some 2,000 militiamen had poured into the city from the surrounding towns, encircling the fort where Governor Andros was stationed with his royal troops. The first officer of the twenty-eight-gun Rose sent a boatload of sailors to rescue the governor, but they, too, were overpowered as soon as they stepped ashore. “Surrender and deliver up the government and the fortifications,” the coup leaders warned Andros, or he would face “the taking of the fortification by storm.” The governor surrendered the following day and joined his subordinates in the town jail. Faced with the guns of the now rebel-held fort, the acting captain of the Rose effectively surrendered as well, turning his vessel’s sails over to the Yankees. In a single day the Dominion government had been overturned.

News of the Yankee rebellion reached New Amsterdam within days, electrifying many of the town’s Dutch inhabitants. Here was an opportunity to put an end not only to an authoritarian government but possibly to the English occupation of their country as well. New York might become New Netherland once again, liberating the Dutch, Walloons, Jews, and Huguenots from the stress of living under a nation that could not be relied upon to tolerate religious diversity and freedom of expression. The colony’s Dominion lieutenant governor, Francis Nicholson, made their choice easier when he declared New Yorkers to be “a conquered people” who “could not expect the same rights as English people.”

Defiant New Netherlanders placed their hopes in William of Orange, who, after all, was the military leader of their mother country and might therefore be persuaded to liberate the Dutch colony from English rule. As the members of the Dutch congregation in New York City would later explain, William’s “forefathers had liberated our ancestors from the Spanish yoke” and “had now come again to deliver the kingdom of England from Popery and Tyranny.” Indeed, the majority of those who took up arms against the government that spring were Dutch, and they were led by a German-born Dutch Calvinist, Jacob Leisler. Opponents would later denounce their rebellion as simply a “Dutch plot.”

But the first disturbances came, not surprisingly, from the Yankee settlements of eastern Long Island, whose people had never wanted to be a part of New York. Longing to join Connecticut and fearful of a French Catholic invasion, they overthrew and replaced local Dominion officials. Hundreds of armed Yankee militiamen then marched on New York City and Albany, intending to take control of their forts and seize the tax money Dominion officials had extorted from them. “We, having like them at Boston, groaned under arbitrary power,” they explained, “think it our bounden duty to . . . secure those persons who have extorted from us” an action “nothing less than what is our duty to God.” The Long Islanders got within fourteen miles of Manhattan before Lieutenant Governor Nicholson organized a meeting with their leaders. He offered the successful gambit of a large cash payment to the assembled soldiers, ostensibly representing back wages and tax credits. The Yankees stopped their advance, but the damage to Dominion authority had been done.

Emboldened by the Yankee Long Islanders, dissatisfied members of the city’s own militia took up arms. Merchants stopped paying customs. “The people could not be restrained,” a group of the city’s Dutch inhabitants reported. “They cried out that the magistrates here ought also to declare themselves for the Prince of Orange.” Lieutenant governor Nicholson withdrew to the fort and ordered its guns trained on the city. “There are so many rogues in this town that I am almost afraid to walk in the streets,” he fumed to a Dutch lieutenant, adding, fatefully, that if the uprising continued he would “set fire to the town.”

Word of Nicholson’s threat spread through the city, and within hours the lieutenant governor could hear the beating of drums calling the rebellious militia to muster. The armed townspeople marched on the fort, where the Dutch lieutenant opened the gates and let them in. “In half an hour’s time the fort was full of armed and enraged men crying out that they were betrayed and that it was time to look to themselves,” one witness recalled. The city secured, the Dutch and their sympathizers anxiously waited to see if their countryman would bring New Netherland back from the grave.

On the face of it, Tidewater seemed an unlikely region to revolt. After all, Virginia was an avowedly conservative area, Royalist in politics and Anglican in religion. Maryland was even more so, with the Lords Baltimore ruling their portion of the Chesapeake like medieval kings of yore; their Catholicism only made them all the more attractive to James II. The king might wish to make his American colonies more uniform, but the Tidewater gentry had reason to believe their own aristocratic societies might serve as a model for his project.

As the establishment back in England began to turn on James, many in Tidewater followed their lead, and for many of the same reasons. Domestically the king was undercutting the Anglican Church, appointing Catholics to high office and usurping powers from the landed aristocracy, fraying the fabric of the English life the Chesapeake elite held so dear. In America, James sought to deny the Tidewater aristocracy their representative assemblies and threatened the prosperity of all planters with exorbitant new tobacco duties. As fears grew that the king was complicit in a Popish plot, the public became convinced that the Catholic Calverts were probably involved as well. On both shores of the Chesapeake, Protestants feared their way of existence was under siege, with those in Maryland convinced their very lives were in danger.

As reports on the crisis in England grew dire in the winter of 1688–1689, Anglican and Puritan settlers across Chesapeake country became alarmed that Maryland’s Catholic leadership was secretly negotiating with the Seneca Indians to massacre Protestants. Residents of Stafford County, Virginia—just across the Potomac from Maryland—deployed armed units to fend off the suspected assault and, according to one Virginia official, were “ready to fly in the face of government.” In Maryland, the governing council reported, “the whole country was in an uproar.” Word of William and Mary’s coronation arrived before the anti-Catholic hysteria got out of hand in Virginia, but it was not sufficient to quell growing unrest in Maryland.

In Maryland, the Calverts’ handpicked, Catholic-dominated governing council refused to proclaim its allegiance to the new sovereigns. In July, more than two months after official word of the coronations had reached Tidewater, the colony’s Protestant majority decided they could wait no longer. The Protestants—almost all of whom had emigrated from Virginia—decided to topple the Calverts’ regime and replace it with one that better conformed to Tidewater’s dominant culture.

The insurgents organized themselves in a ragtag army called, appropriately enough, the Protestant Associators. Led by a former Anglican minister, they marched by the hundreds on St. Mary’s City. The colonial militia dispersed before them, ignoring orders to defend the State House. Lord Baltimore’s officers tried to organize a counterattack, but none of their enlisted men reported for duty. Within days the Associators were at the gates of Lord Baltimore’s mansion, supported by cannon seized from an English ship they’d captured in the capital. The governing councilors hiding inside had no choice but to surrender, forever ending the Calvert family’s rule. The Associators issued a manifesto denouncing Lord Baltimore for treason, discriminating against Anglicans, and colluding with French Jesuits and Indians against William and Mary’s rule. The surrender terms banned Catholics from public office and the military, effectively turning power over to the Anglican, mostly Virginia-born elite.

The insurgents had succeeded in remaking Maryland along the lines of their native Virginia, consolidating Tidewater culture across the Chesapeake country.

While the American “revolutionaries” of 1689 were able to topple regimes that had threatened them, not all of them achieved everything they had hoped for. The leaders of all three insurgencies sought King William’s blessing for what they had accomplished. But while the new king endorsed the actions and honored the requests of Tidewater rebels, he did not roll back all of James’s reforms in either New England or New Netherland. William’s empire might have been more flexible than James’s had been, but it was not willing to cede to the colonials on every point.

The New Netherland Dutch were the most disappointed. William, not wishing to alienate his new English subjects, declined to return New York to the Netherlands. Meanwhile the insurgency itself collapsed into political infighting, with various ethnic and economic interests struggling for control of the colony. The rebels’ interim leader, Jacob Leisler, was unable to consolidate power but made plenty of enemies trying to do so. On the arrival of a new royal governor two years later, Leisler’s foes managed to get him hanged for treason, deepening divisions in the city. As one governor would later observe: “Neither party will be satisfied with less than the necks of their adversaries.” Instead of returning to Dutch rule, New Netherlanders found themselves living in a fractious royal colony, at odds with themselves and the Yankees of eastern Long Island, the upper Hudson Valley, and New England.

More than anything, the Yankees had wanted their various governing charters reactivated, restoring each of the New England colonies to their previous status as self-governing republics. (“The charter of Massachusetts is . . . our Magna Carta,” a resident of that colony explained. “Without it, we are wholly without law, the laws of England being made for England only.”) William, however, ordered that Massachusetts and the Plymouth colony remain merged under a royal governor with power to veto legislation. The Yankees would be given back their elected assemblies, land titles, and unfettered town governments, but they had to allow all Protestant property owners to vote, not just the ones who had been given membership in the Puritan churches. Connecticut and Rhode Island could continue to govern themselves as they had previously, but the mighty Bay Colony would be kept on a tighter leash. If God’s chosen people wished to carry on building their utopia, they would have to fight another revolution.