Ancient Warfare issue XI-4 explores warfare in ancient Israel and the Levant from the period of 1100 – 700 BC.

You can order your copy here:

https://www.karwansaraypublishers.com/ancient-warfare-xi-4.html

In the Old Testament war was considered inseparable from human life. Wars were always considered holy in one way or another. Whenever Israel fought a righteous battle, it was not Israel which fought but the God of Israel. The victory hymn of Deborah provides a fine example of this ideology. Also the story in 1 Samuel about the Ark of the Covenant that was carried into battle against the Philistines relates to this idea of the holy war. On the reverse side, when a battle was lost, it was never the God of Israel who lost it. On such occasions Israel and its kings had transgressed the will of the Lord and were accordingly punished by defeat. Wars were cruel, including mass executions of prisoners and the total extermination of the enemy, men, women, and children. The Hebrew technical term was herem, the ban of God imposed on the enemy, spelling disaster for Israel’s vanquished foes. Thus, when Joshua conquered Jericho and Ai, he placed a ban on these sites. No one escaped their fate, except in Jericho’s case: the prostitute Rahab who had assisted Joshua’s spies (Joshua 2; 6).

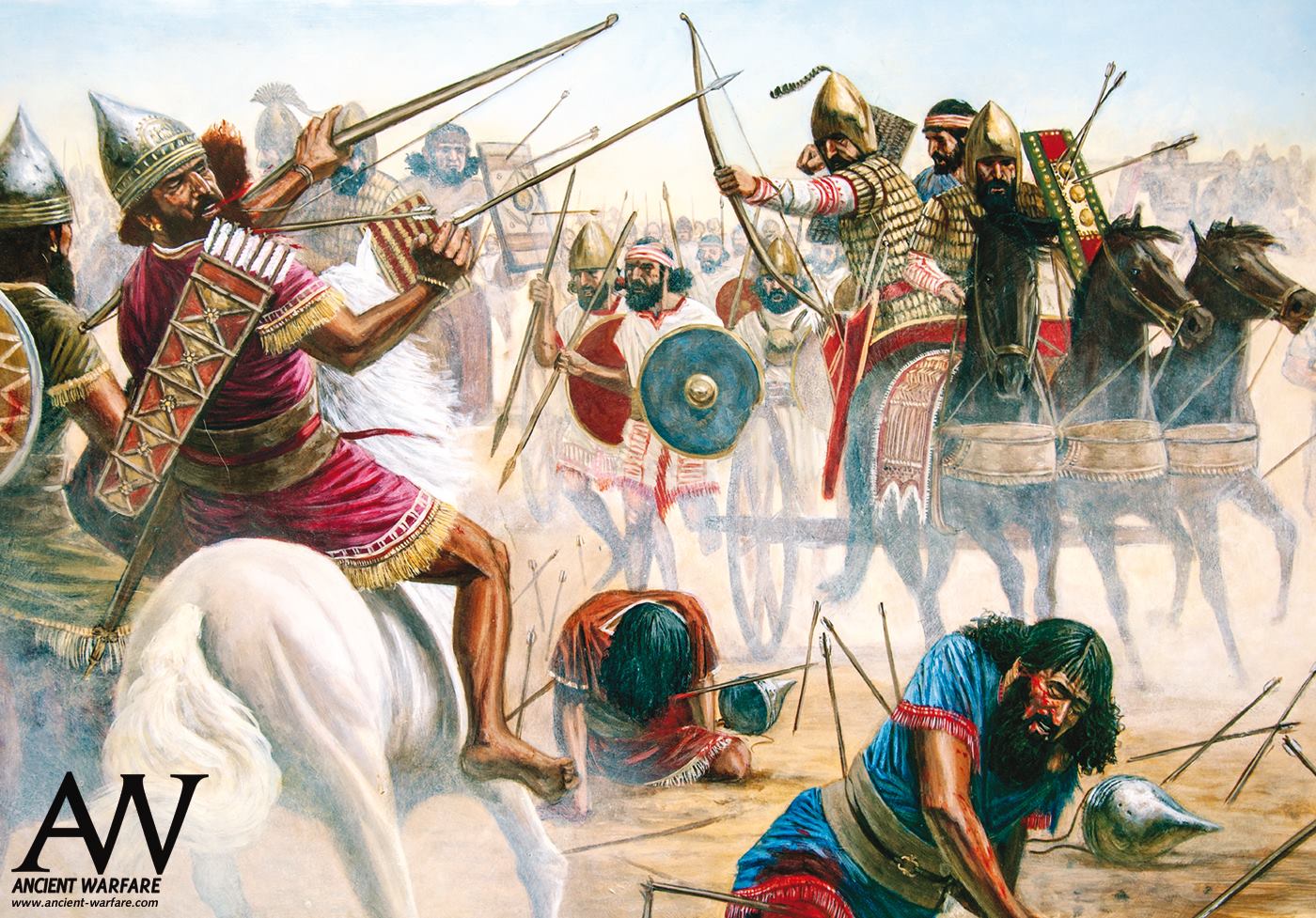

Rather little is known about the development of warfare in ancient Israel. In Late Bronze Age western Asia, including Palestine, war was the business of professional, mostly relatively small armies. The main body of the army consisted of infantry, assisted by a corps of chariots. Only the great powers of that time, such as Egypt or the Hittite Empire, disposed over larger and more specialized military organizations, including light as well as heavy infantry, and an extensive amount of chariots driven by a very specialized elite corps of charioteers. In the Early Iron Age, a rabble of loosely organized tribesmen took over from the professionals, without any indication of specialization into different types of weaponry.

During the time of the Hebrew kingdom, the specialized organization reappeared as seen, for example, in the description of Solomon’s military system (1 Kgs 9:15-23). However, the real change in warfare came with the arrival of the heavy armored Assyrian armies in the Levant in the ninth-eighth centuries. The Assyrians managed to create the most specialized military body the ancient Near East had ever seen, including light and heavy infantry, specialist corps of archers, stone slingers, horsemen, and charioteers. The Assyrians were also innovative when it came to the construction of siege machinery, although they never achieved the professionalism in the procurement of such items as the later Hellenistic and Roman armies. Thus, Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon, laid siege to Tyre for 25 years without any success at all. New developments only occurred in the fifth century when Persian local rulers began to employ Greek hoplites as mercenaries making use of their superior training and morale. The difference between the by now traditional Near Eastern military organization and the Greco-Roman military was exhibited when Alexander the Great crushed the Persian Empire within a couple of years and after that when Rome repeated his success, this time defeating the kingdoms established by Alexander’s generals.

The Old Testament says close to nothing about warfare at sea. The kingdoms of Israel and Judah did not possess a navy. When the imperial powers of Assyria or Persia planned campaigns at sea, they turned to the Phoenicians for help.

JOSHUA.

Joshua (the name means “Yahweh is salvation”) was the Israelite conqueror of Canaan, nominated as “the servant of Moses” already in the desert (Exod 24:13) and installed by Moses as his successor (Num 27:12-23). After Moses’ death he took command over the Israelite tribes and commanded the campaign in Canaan. Here he conquered Jericho and Ai, and reduced the Canaanites to servants of the Israelites (Josh 6-9). When he had finished the conquest, he distributed the territories of Canaan between the Israelite tribes. At the end of his life, he summoned the leaders of Israel to Shechem in order to renew Israel’s covenant with Yahweh (Josh 24). When he died, he was buried at Timnath-serah in the hill land of Ephraim (Josh 24:30).

While Joshua and the conquest tradition were formerly believed to be historical information, at least in part, historical and archaeological investigations have now created a scenario for the history of Palestine in the late second millennium B.C.E. that makes an Israelite conquest of Canaan as described in the Book of Joshua, our main source of knowledge about Joshua, totally unlikely.

JERICHO.

An important city and oasis located in the Jordan valley c. 10 kilometers northwest of the Dead Sea. It is located c. 250 meters below sea level in an almost tropical and highly fertile environment. In the Old Testament it is also occasionally called the “City of Palms” (e.g., Deut 34:3). It was conquered by Joshua (Josh 5-6) and totally destroyed. A curse was put on the man who was going to rebuild Jericho that he shall lose his two sons (Josh 6:26), and it falls on Hiel, who in the days of Ahab rebuilt the city (1 Kgs 16:34).

Jericho is located at Tell es-Sultan on the eastern outskirts of the modern city and oasis of Ariha. It was excavated in the 19th century, and again at the beginning of the 20th century. Excavations were resumed during the British mandate and again between 1952 and 1958. On Tell es-Sultan a settlement existed with roots reaching far back into the Mesolithic period (10th millennium B.C.E.). It was continuously inhabited for most of the Stone Age, abandoned sometime in the fourth millennium, but rebuilt in the Early Bronze Age, and after a new hiatus in its settlement again in the Middle Bronze Age. The city was destroyed c. 1550 B.C.E. and not rebuilt before the seventh century B.C.E. The Iron Age settlement was destroyed probably in connection with the Babylonian conquest of the Kingdom of Judah in 587 B.C.E. The tell was never resettled.

AHAB.

King of Israel c. 874-853 B.C.E. and the most important ruler in his dynasty. The main source on the life of Ahab is supposed to be 1 Kgs 16-22. However, 1 Kgs 17-19 is part of the Elijah and Elisha legends, and 1 Kgs 20 and 22, that tell how intense warfare broke out between Israel and Aram, may have been wrongly placed by the editors of Kings as relevant to Ahab’s time. Ahab is also mentioned in an Assyrian (see Assyria and Babylonia) inscription commemorating the battle at Qarqar in 853 B.C.E. as Ahabbu Sir’ilaja, that is, “Ahab of Israel,” Sir’ilaja most likely being a corrupted form of Israel. He may also be mentioned by the Mesha inscription from ancient Moab, although without a name. Finally, his relations to the Tyrian King Ittoba’al (Old Testament: Ethbaal 1 Kgs 16:31) have been elaborated by Josephus.

The description of Ahab’s reign in the Old Testament is strongly biased and directly misrepresents the deeds of a great king. According to the Old Testament, Ahab was perhaps the most pathetic crook among all his fellow kings. This source can only be used as historical information with the utmost care when it comes to the reign of Ahab. According to the Old Testament, Ahab, provoked by his marital alliance with the Tyrian princess Jezebel, seduced his people into idolatry when he established a sanctuary for her god, Ba’al, at his capital, Samaria, in the heartland of Israel. It is also Jezebel who brought the conflict between Ahab and the Israelite nobleman Naboth to its gruesome conclusion. Ahab failed both when it came to his internal policies and in his foreign affairs. His policies brought upon him and his dynasty a conflict with the supporters of the traditional Israelite God, Yahweh—most notably the two prophets Elijah and Micaiah, the son of Imlah. His foreign policy is said to have ended in disaster when the Aramaeans laid siege to his capital. Finally, according to the Old Testament, Ahab succumbed to the Aramaeans in a battle close to Rabba Ammon (see also Ammon, Ammonites)—present-day Amman.

Although the Old Testament is highly critical of Ahab and his house, it cannot totally cover up that he was a king of eminent importance. Thus the biblical narrative includes some notes that describe his building activities (1 Kgs 16:32-33; 22:39—the last note said to come from “the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel”—by a number of scholars reckoned to have been the official annals of the kingdom of Israel). Furthermore, the note about Ahab’s death in 1 Kgs 22:40 indicates that he did not die violently in a battle but peacefully in his own home at Samaria.

When all the information about Ahab is taken into consideration, a totally different picture emerges from the one in the Old Testament. Ahab inherited from his father, King Omri, a relatively wealthy kingdom and was able to hand over to his son and successor a well-established and consolidated kingdom. He established a series of connections to Phoenicia through his marriage policies, and entertained a perfect relationship with the important Aramaean state of Damascus to the east and its northern neighbor, the kingdom of Hamath. Between the state of Israel and its southern neighbor, the petty kingdom of Judah, another marital union was created, between Ahab’s sister (2 Kgs 8:26) or daughter (2 Kgs 8:18) Athaliah and the king of Judah—either Joram or Ahaziah. According to the Moabite Mesha inscription, Mesha was able to liberate his kingdom from Israelite supremacy, although—according to the OT—this only happened in the days of Ahab’s successor, Joram. The clearest example of Ahab’s greatness may be his contribution to the Syrian anti-Assyrian coalition that fought and won the battle of Qarqar. In this alliance between, among other states, Damascus and Hamath, Ahab contributed with an enormous contingent of chariots. It may be correct, as maintained by the Old Testament, that his religious policies created problems within his own kingdom, but excavations in Palestine show that his building activities were indeed considerable. Important remains from his time have been excavated—apart from Samaria—at Megiddo, Hazor, and Jezreel.

BATTLE OF QARQAR.

The place of a battle between the Assyrian army of Shalmaneser III (858-823) and a coalition of states from Syria and Palestine. Qarqar has not yet been identified with certainty but was located in the Orontes Valley in Syria. The importance of this battle is not limited to its outcome—the coalition managed temporarily to stop the Assyrian advance to the west—but the date of the battle has been linked to a solar eclipse that happened that year. This coincidence has made the battle a sort of pivotal point in the establishment of ancient Near Eastern chronology of the early first millennium B.C.E.