This achievement of the German aircraft industry, which had been seriously affected by the economic crisis, was indeed impressive. At the end of January 1933 the producers of airframes and motors belonging to the Reich association of the aircraft industry employed scarcely more than 4,000 workers. The achievements of the most important producers-Junkers in Dessau, Heinkel in Warnemünde, Dornier in Friedrichshafen, and the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke in Augsburg-in the area of aircraft development were significant, but their production capacity was limited because of the economic crisis and the special financial problems of their industry. State Secretary Milch, the head of the ministry of aviation under Göring, was himself a former Lufthansa director, thoroughly familiar with conditions in the industry and able to evaluate its potential contribution to the armament programmes. A precondition for the build-up of an air force comparable to those of other European powers was, in addition to considerable funds for the expansion of production, above all the rationalization of the industry. At the beginning ofJune 1933 a ministerial conference took place under Hitler’s chairmanship at which Schacht explained his plan to finance job-creation and rearmament, and thus the expansion of the aircraft industry, by means of the famous ‘Mefo’ bills. In the same month the head of the administrative department of the ministry of aviation, Colonel Kesselring, was sent to Ernst Heinkel at Warnemünde to persuade him to build a new factory near Rostock with a starting labour force of 3,000 workers. Kesselring was successful. The result of the ministry’s initiative, which affected the whole industry, was a sharp and continuous rise in the number of persons employed in aircraft production. The figure rose from about 4,000 in January 1933 to 16,870 at the beginning of 1934 and 59,600 on 1 April 1935. A year later it reached 110,600; on 1 April 1937 it was about 167,200, and on 1 October 1938, 204,100 people were working in the aircraft industry, not including those employed by companies providing equipment and repairs). The labour force in the industry as a whole had thus increased fiftyfold in five and a half years.

The rationalization of production was also carried out on the initiative of the aviation ministry. The best-known example in this area was the Junkers firm. In Dessau Junkers was able to produce only eighteen Junkers 52 aircraft per annum before 1933, if at the same time no other models were produced. After the removal of the founder of the company, Professor Hugo Junkers-due to an inextricable mixture of personal, political, and financial motives of rival groups within the company and the ministry of aviation-Milch informed Klaus Junkers in August 1933 about the ministry’s armament plans, which called for the purchase of 179 Junkers 52s in 1934 alone. Such an order could only be filled if production methods were radically changed. With the decisive help of one of their directors, Koppenberg, Junkers developed the so-called ‘ABC programme’ in the following months, under which mass production of the Junkers 52 was begun around the end of the year. In this programme a number of small firms supervised by Junkers produced individual parts. Only the final assembly of the aircraft was done in the factory at Dessau. This represented a decisive step in the efficient organization of supply firms and at the same time marked the beginning of co-operation among the aircraft producers, who until then had jealously guarded their independence. The way was thus open for the introduction of licensing, which acquired increasing significance in the following years. Between 1933 and 1945 a total of 17,552 Junkers aircraft were built under licence by other firms. The expansion of production under licence was also a consequence of the fact that as early as 1933 the clear prospect of a boom and higher profits in the aircraft industry attracted a growing number of firms.

In this way Secretary Milch and the technical office of the ministry of aviation under Colonel Wimmer, working in close co-operation with the producers, laid the foundations for the Luftwaffe build-up in a surprisingly short time. The mobilization exercise planned by Milch and Wimmer from the beginning of 1935, and conducted between October and December of that year, in the Arado plant in Brandenburg can be considered a test of the success of this method. In eighteen weeks monthly production rose from twenty to 120 aircraft, the size of the factory was nearly doubled, and the labour force tripled. Although this demonstration of efficiency was convincing, it also revealed weaknesses in the production process which the ministry could only partially overcome on its own. The availability of raw materials and above all machine-tools turned out to be unsatisfactory. It was considered less serious that the lodging of extra workers in barracks had a negative effect on productivity and that difficulties arose in one case in starting production under licence.

The Arado experiment proved that the industrial basis for the Luftwaffe build-up had been created in a surprisingly short time. The question was, however, what the dimensions and technical requirements of such a build-up should be. Milch’s programme of 12 July and 28 August 1933 for the first and second build-up periods, 1934 and 1935, had placed the main emphasis on the creation of bomber formations, as Knauss had wanted, but the aircraft planned for these formations did not meet his technical performance standards, nor was the preference given to bombers based on a general consensus of all departments concerned. The Truppenamt of the army command was quite prepared to acknowledge the importance of a bomber fleet for the conduct of a future war, but rejected Knauss’s arguments in this regard as completely one-sided and pointed out that, in the future, wars would still be won by the co-operation of all services. Finally, in a directive of 16 August 1933, Blomberg explained that no build-up of a ‘strategic Luftwaffe’ was planned. The objective was rather to create an ‘operational’ Luftwaffe that-either independently and supported by squadrons of long-range reconnaissance aircraft, or in co-operation with the army and navy-would take over operational functions within the framework of a total strategy in the event of a war on several fronts against Poland, France, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia. Moreover, Blomberg indicated that the army and navy would still have their own air units.

Within the framework of such an operational air fleet, the bomber formations Knauss had described still had a special deterrent function. However, in the winter of 1933-4 a Wehrmacht war game suggested by the operations department of the Truppenamt showed that the bomber fleet alone could not eliminate hostile air forces quickly enough, and that Germany’s exposed position urgently required a strong air defence in the form of fighter units and flak artillery.

In the programme he had signed on 28 August 1933 for the second build-up period, 1935, Milch announced an additional programme for ‘total armaments plan for 1934-8’, which would have to take into account ‘the requirements of national defence and the technical possibilities’. The organizational, personnel, and industrial conditions for this programme had been created by the beginning of 1934, and the military tasks of the Luftwaffe had been clarified by the Wehrmacht war game. The aircraft procurement programme of I July 1934 was based on these conditions and represented a continuation of a revised purchase programme of January 1934 for the first and second phases of the build-up. The ‘July programme’ of 1934 was the first long-term programme for the Luftwaffe and envisaged the purchase of 17,015 aircraft of all kinds by 31 March 1938. The importance of this programme is shown by the fact that, at Hitler’s request, Göring and Milch reported to him on it at the end of July. Milch, whom Hitler evidently valued as an expert and man of ideas, was able in the end to resist Hitler’s demands to increase and accelerate the Luftwaffe build-up. At the end of August 1934 Hitler approved a cost estimate for the programme, amounting to RM 10,500m. This clearly showed the special position of the Luftwaffe in relation to the other two services. It was not Blomberg, the defence minister, who presented the financial requirements of an integrated Wehrmacht armaments programme; instead Göring, as the second man in the state, was able to advance the interests of his own service with only an informal agreement with Blomberg. Of the enormous number of aircraft in the July programme only 6,671 were to be combat aeroplanes. They consisted of the following types:

Fighters 2,225

Bombers 2, 188

Dive-bombers 699

Reconnaissance aircraft 1,559

The proportion of combat to training aircraft reflected the awareness of the Luftwaffe leadership that the consolidation of the service would be the most important objective in the coming years and that therefore the main emphasis should be placed on training in all areas. The surprisingly large number of fighters was a result of the Wehrmacht war game in the winter of 1933-4, which had led to a strengthening of the air defence components of the total programme. The programme itself was based on the plan for an operational Luftwaffe as Blomberg had described it in his directive of August 1933.

In the first phase of its realization a total of 3,021 aircraft were to be delivered to the Luftwaffe by 30 September 1935; more than half of them were to be used for training. To achieve this objective, it was planned to increase monthly aircraft production from seventy-two in January 1934 to 293 in July 1935. Thus, the industry was expected to quadruple its production in a relatively short time. At the end of December 1934 1,959 aircraft had already been delivered; the shortfall compared with the plan figure was only 6 per cent. This was indeed an impressive accomplishment; the planning figures of the ministry of aviation and existing production capacity were almost identical.

For a long time at home and abroad, the certain result of the Saar plebiscite in January 1935 had been considered an event which Hitler would use for new foreign-policy and armament initiatives. On 26 February, even before the final re-integration of the Saar on 1 March and the proclamation of general conscription in Germany on 16 March, Blomberg had ordered the gradual removal of the camouflage measures for the Luftwaffe. In an interview on 10 March Göring emphasized its purely defensive character, while Hitler told the British foreign secretary on 25 March that the Luftwaffe had already reached the strength of the Royal Air Force! This was in accord with instructions put out by the Wehrmacht office, probably not without Blomberg’s approval, that it was important to give other countries the impression that Germany now had a strong Wehrmacht capable of fulfilling its tasks even under difficult conditions. For the Luftwaffe, which at this time had about 2,500 aircraft, of which 800 could be used in combat in the event of war, this marked the beginning of a new phase in its political function as a ‘risk Luftwaffe’.

In his directive of 28 August 1933 Milch had stated two conditions for the overall programme in 1934-8: on the one hand it must provide an adequate national defence, and on the other it must make use of possibilities provided by technology. The astonishing fulfilment of planning goals combined with the obvious deterrent effect on other countries, however achieved, demonstrated convincingly that the Luftwaffe met the requirements of national defence in these years. But to what extent did the total programme take into account technical possibilities? The 270 bombers delivered by the end of 1934 were Junkers 52s and Dornier IIs; the ninety- nine single-seat fighters were Arado 64 and 65 biplanes. In the service and in the ministry of aviation there was complete agreement that these models were technically obsolete. Milch was well aware of this situation; he had rejected Hitler’s demand to increase production still further with the argument that it would result in too many obsolete aircraft. Major von Richthofen, the head of development in the technical office of the ministry of aviation, expressed the guiding principle of this first phase succinctly in August 1934: ‘An aircraft of limited usefulness available now is better than none at all.’ The new models, especially the medium- range bombers such as the Dornier 17, the Heinkel 111, and the Junkers 86, as well as the Junkers 86 dive-bomber, were already being developed. But the question was when they would be ready for mass production after the lengthy process of development and testing. Moreover, there was a serious problem in the development and production of aircraft engines. Only Junkers had been involved continuously in their further development in the 1920s. Daimler-Benz and BMW (Bayerische Motorenwerke) had no previous experience in this area. The use of funds from the ministry of aviation, which had been so successful in the build-up of the airframe industry, was of only limited effectiveness in this case. Of course the expansion of capacity was supported as far as possible, but Richthofen’s demand at a conference with the producers of aircraft motors on 20-1 September 1934 that the time required for the development of a new motor be reduced from five or six to two years simply ignored reality.

The objective of equipping the Luftwaffe units with new and better aircraft, for which Milch and the technical office had been striving since 1934 at the latest, clearly was not reached as planned. The development and testing of models and motors, and their mass production, were a process which could be directed and planned only to a limited extent. The previous planning of the ministry of aviation had promoted the production of aircraft which it knew would be obsolete in a short time, not only in the interest of national defence but also because an efficient aircraft industry could only be created in that way. After the first measurable success had been achieved at the end of 1934 and the beginning of 1935, re-equipping could be carried out only gradually, in order to avoid having to close factories until the new models were ready for mass production. The many supplementary programmes of 1935 and the first half of 1936 must be understood against this background. In January and October 1935 Milch approved procurement and delivery plans that went beyond the July programme of 1934 and were intended, e. g. in the case of bombers, to permit the discontinuation of the old models and increased production of new ones, such as the Heinkel 111, the Dornier 17, and the Junkers 86. Pressure from Hitler and Göring in setting constantly increased production requirements probably also played a significant role. Although the re-equipping process required much more time and was actually carried out only in 1937, planning remained astonishingly flexible until the summer of 1936. For example, production of the Junker 52, which had been considered a stop-gap solution from the very beginning, was continued until the new bomber models could be put into mass production. The Junkers 52 later became the most important transport aircraft of the Luftwaffe.

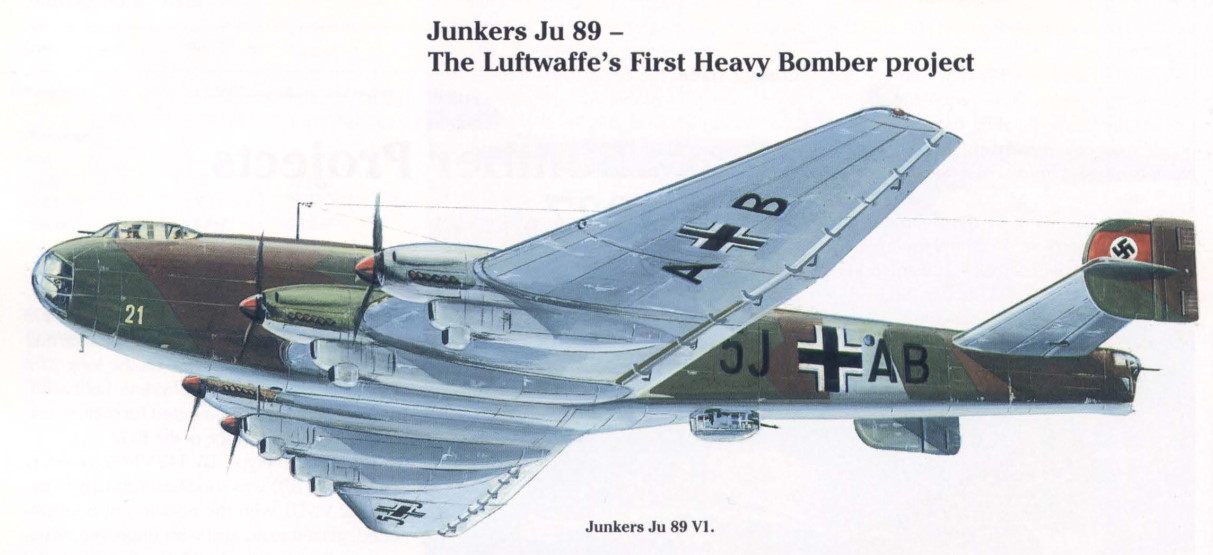

The flexibility in planning, however, clearly went along with uncertainty as to the technical and military requirements for the individual types of aircraft, and this had a lasting, negative effect on the development process. This effect had already become obvious in the development of a new two-engine horizontal bomber316 and would also be the fate of the four-engine strategic bomber. The aviation officers of the Reichswehr had already worked on this project. Colonel Wever, the head of the Luftkommandoamt (air command office), who had concerned himself intensively with the problems of air warfare, quickly recognized its importance. As early as May 1934 a development contract was awarded to Junkers and Dornier. The bomber was to be ready for mass production as early as 1938, but before the test flights of the Junkers 89 and the Dornier 19 had taken place doubts were expressed as to whether they had adequate speed and range. The motor problem also played a decisive role. On 17 April 1936 Wever approved guidelines for the further development of the strategic bomber. The existing prototypes could not meet the new requirements. The result was that, after Wever’s death on 3 June 1936, development of the bomber was delayed even further and finally dropped from the general development programme. The reasons for this decision and its consequences cannot be determined with adequate clarity. It is as difficult to answer the question whether Germany had the economic means to build a large strategic air fleet as it is to determine whether the engine question was decisive. Undoubtedly, however, Wever’s death and the subsequent far-reaching personnel changes in the ministry of aviation led to the decision being made, as it were, incidentally, in a manner not appropriate to the importance of the question.

Wever’s death marked the end of a significant period in the build-up of the Luftwaffe. The years 1933-6 were characterized by the work of a number of competent officers as heads of the offices in the ministry of aviation, which was directed less by Göring than by Milch. The available evidence indicates that Milch and the colonels Wever, Wimmer, Kesselring, and Stumpff developed a close working relationship with clear objectives; they showed considerable foresight in laying the foundation for the build-up of the Luftwaffe in the following years, during which the leadership of the ministry underwent decisive change. In addition to the successful development of the aircraft industry, which was due essentially to the initiative of Milch, Wimmer, and Kesselring, above all Wever had thought out and defined the military function of the Luftwaffe in its enlarged form. As an army general staff officer and former head of the training department of the Truppenamt, he had mastered the new problems surprisingly quickly and, like Milch, had recognized the strategic and operational possibilities of air warfare with the help of a bomber fleet as described by Knauss in his memorandum. At the same time, however, he had rejected as dangerous the one-sidedness of Douhet’s ideas. Typical of all armament programmes for which he was even partly responsible was the priority given to the bomber. This was also true of the July programme of 1934, if the planned numbers of horizontal and dive-bombers are added together. As a result of the Wehrmacht war-game of 1933-4, Wever did place more emphasis on air defence, but it should not be forgotten that the strategic bomber was developed on his initiative, and one can only speculate about what solution he would have chosen after the decision of 17 April 1936.

Wever expressed his opinions succinctly in Luftwaffe regulation 16 on ‘Air Warfare’, issued in 1936, which marked the change from a purely ‘risk Luftwaffe’ designed to protect Germany until rearmament was completed. This document reflected the conviction that the first and only decisive task of the Luftwaffe was to conduct an offensive against the very broadly defined ‘fighting ability of the enemy’ and the ‘adversary’s will to resist’. From these general functions Wever deduced three main tasks: (1) ‘the war against the enemy air force’; (2) direct support of the operations of the army and the navy; and finally (3) the ‘war against the sources of strength of the enemy forces’ and the disrupting of the ‘flow of strength’ from these sources to the front. The Luftwaffe could attack ‘the hostile nation’ at the most sensitive point, at its ‘roots’, as Wever expressed it elsewhere. In its own eyes the Luftwaffe had already developed far beyond the role of a mere support weapon for the army and navy. The regulation covered all elements of modern air warfare. The variety of possible uses for the Luftwaffe led to the conclusion that air warfare was conceivable only within the framework of the general conduct of a war: ‘The politico-military leadership must, therefore, continue to determine the aims of air warfare’ (point 11). A slight uncertainty, however, remained in the attempt to define more precisely the co-operation with the army and navy. If one compares these thoughts on air warfare with the views of the leaders of the other two services, it is clear that, in contrast to his counterparts in the army and navy, Wever had retained an overall view and had shown how the Luftwaffe could act independently as well as together with the other services.

The Luftwaffe build-up in the years 1933-6 was a period of comprehensive and cautious planning in which the Luftwaffe leaders tried to take into account the political, military, and technical-industrial factors involved in armaments programmes, although the difficulties and weaknesses, above all in personnel build- up and training, were obvious. These very energetic and successful efforts were reminiscent of the naval build-up before the First World War, and differed strikingly from the narrow perspectives under which the armament programmes of the other two branches of the Wehrmacht were carried out.