More than the rearmament of the army and the navy, the spectacular development of the Luftwaffe in the six years from 1933 until the outbreak of the war aroused the boundless admiration as well as the dark forebodings of contemporaries. Even today the inventions and brilliant technical achievements of those years in the area of aircraft and rocket construction are still surrounded by myths which lend the brief history of the Luftwaffe a special glory, in spite of its ultimate failure. The change from the biplane to the first jet fighter in the world, from the three ‘aerial advertising squadrons’ of 1933 to the 4,093 front-line aircraft at the beginning of the war was indeed without parallel in the short history of military aviation. It inevitably reminds one of the German fleet programme under William II and Admiral von Tirpitz between 1897 and 1914, but not of the work of Tirpitz’s epigone Raeder. Above all, the immediate secondary effects of the fleet and the Luftwaffe, both of them eminently the products of modern industrial technology, were very similar. In both cases fascination with new possibilities opened up by a new weapon combined with a nationalistic claim to great-power status to produce an awareness of power that led to quite similar consequences in foreign policy. The diplomatic, political, and military reaction of Britain to the perceived threat of the German naval and later the Luftwaffe build-up demonstrates this fact with startling clarity. But this similarity probably did not extend to the political and military motives behind the Luftwaffe build-up. Moreover, it must be asked whether this build-up did not differ fundamentally from the imperial fleet construction programme of the turn of the century, because of its greater dependence on technology and the resulting planning and economic problems. Nevertheless, the similarity, which was also noticed by contemporaries, may provide better insights into the political and military problems involved in the Luftwaffe build-up.

The ‘Risk Luftwaffe’ 1933-1936

The ideas developed within the framework of general Reichswehr planning concerning the future creation of an air arm have already been mentioned. Essentially they envisaged the use of air power to support the army and navy. Specific organizational and technical as well as personnel and material measures, some of which were very significant, had already been taken in accordance with this objective. The appointment of Göring as Reich commissioner for aviation on 30 January 1933 and of Erhard Milch as state secretary in Göring’s Reichskommissariat seemed to mark a basic change in this area. Immediately after his appointment Milch indicated that the Reichskommissariat should be considered only an interim stage on the way to a Reich aviation ministry, which would be responsible for all areas of civil and military aviation. When this ministry was created by a decision of the president and a decree of Defence Minister von Blomberg on 10 May 1933, it represented more than a centralization of all branches of aviation. Göring’s influence within the Party and his many positions and tasks in the government meant that the status of the Luftwaffe as an independent service within the Wehrmacht was secured once and for all without the loss of time and energy connected with similar developments in other countries. The army and especially the navy did not accept this drastic limitation of their authority over air units without resistance. They attempted to regain the lost ground, but all their efforts failed because the most important man in the Nazi movement after Hitler had set himself the task of creating an independent Luftwaffe as an appropriate expression of Germany’s claim to be a great power. Of course the status of an independent service also offered new possibilities in setting and planning armament targets.

Milch, who was the driving force behind the planning and realization of the Luftwaffe armament programme until the end of 1936, concerned himself after April 1933 at the latest with drafting a new arms plan for the service. In May he received a memorandum from the Lufthansa director Dr Robert Knauss on ‘The German Air Fleet’, containing ideas with which he declared his ‘complete’ agreement. As this memorandum received Milch’s approval, it can be considered the earliest authoritative statement reflecting the views of the air ministry chiefs on the basic principles of air warfare.

Knauss’s basic assumption was that the goal of the ‘national government’ was to ‘re-establish Germany’s position as a great power in Europe’, and that this goal could only be reached by a rearmament that would at least permit Germany to fight a ‘two-front war against France and Poland with prospects of success’. In Knauss’s opinion, there was no more effective means than the creation of a strong air force to shorten the ‘critical period’ required for the realization of this aim. For him ‘the most important feature of the Luftwaffe as an independent service was the ‘long- range, operationally mobile striking power of its bombers’. This ‘would greatly increase the risk for any conceivable enemy in a war’ and would reduce the danger of a preventive attack against a Germany that was regaining its strength. The striking feature of this plan for a ‘risk Luftwaffe’ was not only its revival of Tirpitz’s military theory, but primarily that it closely followed Hitler’s views in his talk to the Reichswehr leaders on 3 February 1933.

The most important factor in determining the effect of the memorandum was probably that Knauss was not content to present his suggestion for a ‘risk Luftwaffe’ and embellish it with ideas of the Italian aerial warfare theoretician Douhet. He described in detail the operational possibilities as well as the tactical and organizational principles and requirements for the aeroplanes to be produced, and argued that they were quite achievable. This gave his programme clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness.

Specifically, Knauss proposed the rapid, secret creation of a force of about 390 four-engine bombers supported by ten air reconnaissance squadrons. He believed it would be possible ‘to prepare the necessary personnel and material measures by using the army aviation units and the Lufthansa organization in such a way that they could be combined to form an air force in a surprisingly short time’. He was convinced that such a highly mobile, operational military instrument would give Germany decisive advantages in a possible conflict with France and Poland, but more important in his view was the expected deterrent effect of the ‘risk Luftwaffe’. To achieve his military objectives, Knauss argued forcefully for an armament policy with clear priorities. ‘Equal rearmament in all areas’ would lead to a ‘waste of energy’ and increase the danger of a preventive attack. In the risk phase of German rearmament, the rapid creation of five army divisions or the construction of two pocket battleships would only slightly change the balance of military power in Europe. This argument was directed primarily against the known construction plans of the navy. Knauss explicitly rejected the Tirpitz policy and, in the interest of national defence, assigned the navy only a defensive function in the North Sea and the Baltic. He explained that the funds required for the construction of two pocket battleships would be sufficient to build an air fleet of 400 large bombers, which would ‘secure Germany’s air superiority in central Europe within a few years’. But within the air programme too Knauss demanded clear priorities. Especially striking was his rejection of any operational function for fighter aircraft and his description of them as only support weapons for the army and the navy. For him the only important goal was the creation of a bomber fleet and the attached reconnaissance squadrons. He concluded his arguments for a ‘risk Luftwaffe’ and its great importance for the success of general rearmament by pointing out that in Italy and France the idea of independent, operational air warfare had many supporters, and that especially the new French minister of aviation, Pierre Cot, had already taken the first steps in this direction. Any delay would therefore reduce the ‘lead Germany can gain today, perhaps for a decade, by creating an air fleet’, and ‘precisely that decade would be decisive’. Knauss professed himself optimistic, for the ‘enormous dynamism of the national government’ and the ‘leadership qualities of the first German minister of aviation’ were the best guarantee that the ‘life-or- death decision’ regarding the Luftwaffe build-up would be made quickly and that all resistance to carrying it out would be overcome.

In spite of Milch’s agreement, the effect of Knauss’s memorandum on the armament planning of the Luftwaffe cannot be precisely determined. On Milch’s orders the responsible departments of the newly founded ministry of aviation had been studying the possibilities of a first, large-scale aircraft procurement programme since the beginning of May. His suggested objective of 1,000 aeroplanes for the first build-up phase in 1933-4 proved to be somewhat unrealistic at first because of the small capacity of the German aircraft industry. As early as June 1933 preparations had reached a point at which Milch and the head of the Ministeramt in the defence ministry, Colonel von Reichenau, were able to agree on a provisional armament programme, which was approved by Göring and Blomberg around the end of the month. This envisaged the creation of an air fleet of about 600 aeroplanes in fifty-one squadrons by the autumn of 1935. lB1 In contrast to all previous air armament programmes, this one was characterized by a strong emphasis on bomber squadrons. The backbone of the air fleet was to be twenty- seven bomber squadrons in nine groups. This programme, which was changed slightly in August and September, was only partially compatible with Knauss’s ideas, for neither did the air fleet consist of the uniform type of heavily armed bomber he wanted, nor was it to be as large as he had recommended. Nevertheless, about 250 bombers were to be available for combat by the autumn of 1935. Without setting a date for achieving his target, Knauss had demanded a fleet of about 400. On the other hand, the basic features of the programme clearly reflected the idea of the ‘risk Luftwaffe’. The bomber groups were to form the core of the future Luftwaffe and assume the political and military deterrence functions Knauss had assigned to them.

And although the Luftwaffe created on the basis of this programme was indeed inadequate, it fulfilled its political tasks from the very beginning far better than Knauss had demanded. His air fleet had been conceived primarily as a weapon against Germany’s continental neighbours, especially France and Poland. Paradoxically, however, it produced the strongest political reaction in Britain, a country Knauss had not mentioned at all in his memorandum and which could not be seriously threatened by the aircraft of the first German armament programme. The first signs of public concern in Britain about the Luftwaffe build-up could be observed as early as the summer of 1933. This concern was intensified by developments in Germany and by the German withdrawal from the League of Nations and the disarmament conference. The threat from the air and the graphic description of all its possible aspects soon became a constant subject in the British media. Baldwin’s statement in the House of Commons on 30 July 1934 that, in view of the developments in military aviation, Britain’s line of defence was no longer the cliffs of Dover but the Rhine marked the first high point of this general anxiety. Compared with other European air forces, the German Luftwaffe was still weak at the end of 1934; its number of usable, front-line aeroplanes is estimated at about 600. This modest force had, however, created a situation which permitted Hitler to negotiate with Britain about an air pact. In the first phase of its build-up, which at least bore some similarity to Knauss’s principles, the Luftwaffe had fulfilled its intended purpose. There is no evidence of how the air force leaders reacted to this overestimation of their capabilities or what conclusions they drew. But it is improbable that they were completely unaffected by the public debate. It is rather more likely that, in contrast to the starting situation Knauss had described, Britain began to assume an increasingly important role in the thinking of the Luftwaffe leaders. At first it was not, of course, included in their operational planning, but it was regarded more and more as a competitor and a standard by which the Germans measured their own accomplishments. Thus, the political effects of the ‘risk Luftwaffe’ were much more far-reaching than originally intended and opened up possibilities beyond the first, limited objectives.

Knauss had written his memorandum at a time when the first organizational decisions for the build-up of an independent service had been taken, but the personnel and material decisions were still open. The ministry of aviation created by Blomberg’s decree of 10 May 1933 was composed of Göring’s Reichskommissariat and the recently organized Luftschutzamt (air-defence office) of the defence ministry, with responsibility for ‘aviation and air defence of the· army and navy’. The scale of German efforts in this initial phase can be judged by the fact that at the beginning of June 1933 the staff of the ministry consisted of only seventy- six active and retired officers. Moreover, as a result of the long years of intensive preparation by the army and navy, the state secretary in the air ministry was also in charge of the first flying units camouflaged as ‘aerial advertising squadrons’: i.e. the flying school command organized in February 1933, which was responsible for the military departments of the civilian schools in Brunswick, Jüterborg, Schleißheim, Warnemiinde, and Würzburg, as well as the German military aviation centre at Lipetsk in the Soviet Union. These institutions formed the essential organizational foundation for the Luftwaffe build-up. On the whole, probably only a relatively small number of people were involved in German military aviation in the summer of 1933. Under the provisions of the treaty of Versailles, which were still in force, an expansion of the Luftwaffe seemed possible only if all executive organs of the state, especially the Reichswehr and the transportation ministry, actively supported the new service.

At the commanders’ conference following the inauguration of the ministry of aviation, Blomberg took the opportunity to emphasize that the ‘flying officer corps’ should be an ‘elite corps’ imbued with ‘an intensely aggressive spirit’; its ‘preferential treatment in all areas’ was necessary and should be accepted by the other services. After they had been prepared for the new situation in this way and concrete planning had begun in the ministry of aviation, Blomberg informed his commanders at the beginning of October 1933 how far the army and navy were expected to contribute to the personnel build-up of the Luftwaffe. According to his figures 228 officers up to the rank of colonel had already been transferred to the Luftwaffe; an additional seventy were to follow by January 1934. About 1,600 non-commissioned officers and men had also been transferred. For reasons of secrecy the Luftwaffe continued to be dependent on the support of the army and navy in the following years. After 1934 it took over its own recruiting, but its personnel were still trained in units and schools of the other two services until 1935. According to Blomberg an additional 450 officers were to be transferred to the Luftwaffe by 1 April 1934; in the following years the Luftwaffe would itself have to recruit 700 officer cadets each year. Blomberg stressed that nothing would be more short-sighted than the transfer of poorly qualified personnel to the Luftwaffe; it needed rather ‘the best of the best’. At subsequent commanders’ conferences Blomberg continued to support energetically the wishes of the Luftwaffe in personnel questions and did not exclude compulsory transfers. The transfers to the Luftwaffe from the army and navy continued in the following years; in a survey of personnel requirements in December 1938, a result of Hitler’s armament demands, the transfer of army officers was taken for granted. A large number of young civilian pilots also joined the Luftwaffe officer corps at the beginning of 1934; so, after 1 April 1935, did officers of the flak artillery, the air signals corps, and the local defence units, the later supplementary reserve officers.

This incomplete survey clearly shows the difficult problems facing the Luftwaffe personnel office created on 1 October 1933, which had the task of forming a uniform officer corps under difficult conditions on the model of the other two services in the first phase of the secret build-up. From 1 June 1933 onwards the personnel system of the Luftwaffe was under the direction of Colonel Stumpff of the old army (Reichsheer), who became chief of the Luftwaffe general staff in June 1937. The difficult problems he faced can be better understood if one remembers the emphatic, gloomy warnings of the chief of the army personnel office in the summer and winter of 1935 against a new, accelerated expansion of the army. In addition to the necessity if forming the very difficult groups from varied professional backgrounds and experience in the other services and branches of the Luftwaffe into a uniform officer corps, Stumpff was confronted with the problem of familiarizing the new officers with the complex technology of their weapons, as competent leadership at all levels was impossible without such knowledge. Both these tasks, the formation of the officer corps and familiarization with the new technology, could be fulfilled, if at all, only in a lengthy process. The rapid, even over-hasty build-up between 1933 and 1939 created the worst possible conditions for such a development. The figures on the growth of the officer corps and personnel strength provide an impressive picture of the difficulties to be overcome. When camouflage measures were abandoned in the spring of 1935, the officer corps consisted of 900 flying and 200 flak officers commanding about 17,000 non-commissioned officers and men. Two and a half years later, at the end of 1937, the size of the officer corps had increased fivefold: in the three branches of the Luftwaffe there were slightly more than 6,000 officers. By August 1939 the corps had grown to more than 15,000 officers; the number of NCOs and men had risen to 370,000. Thus, after March 1935 the officer corps grew thirteen-fold in barely four and a half years. In view of the fact that, unlike the army, the Luftwaffe officer corps did not have a relatively broad, homogeneous base, it was probably lacking in the coherence necessary for the performance of its military functions. A particularly serious shortcoming was the fact that the entire senior officer corps of the Luftwaffe consisted of former army officers, who at first viewed the far-reaching possibilities of independent air warfare with skepticism and, above all, possessed no experience in commanding large air units. This problem was caused by the nature of the Luftwaffe build-up and could not be overcome before the outbreak of war. It is interesting that Dr Knauss, a director of Lufthansa, did not mention the personnel problems connected with the ‘risk Luftwaffe’ at all in his memorandum.

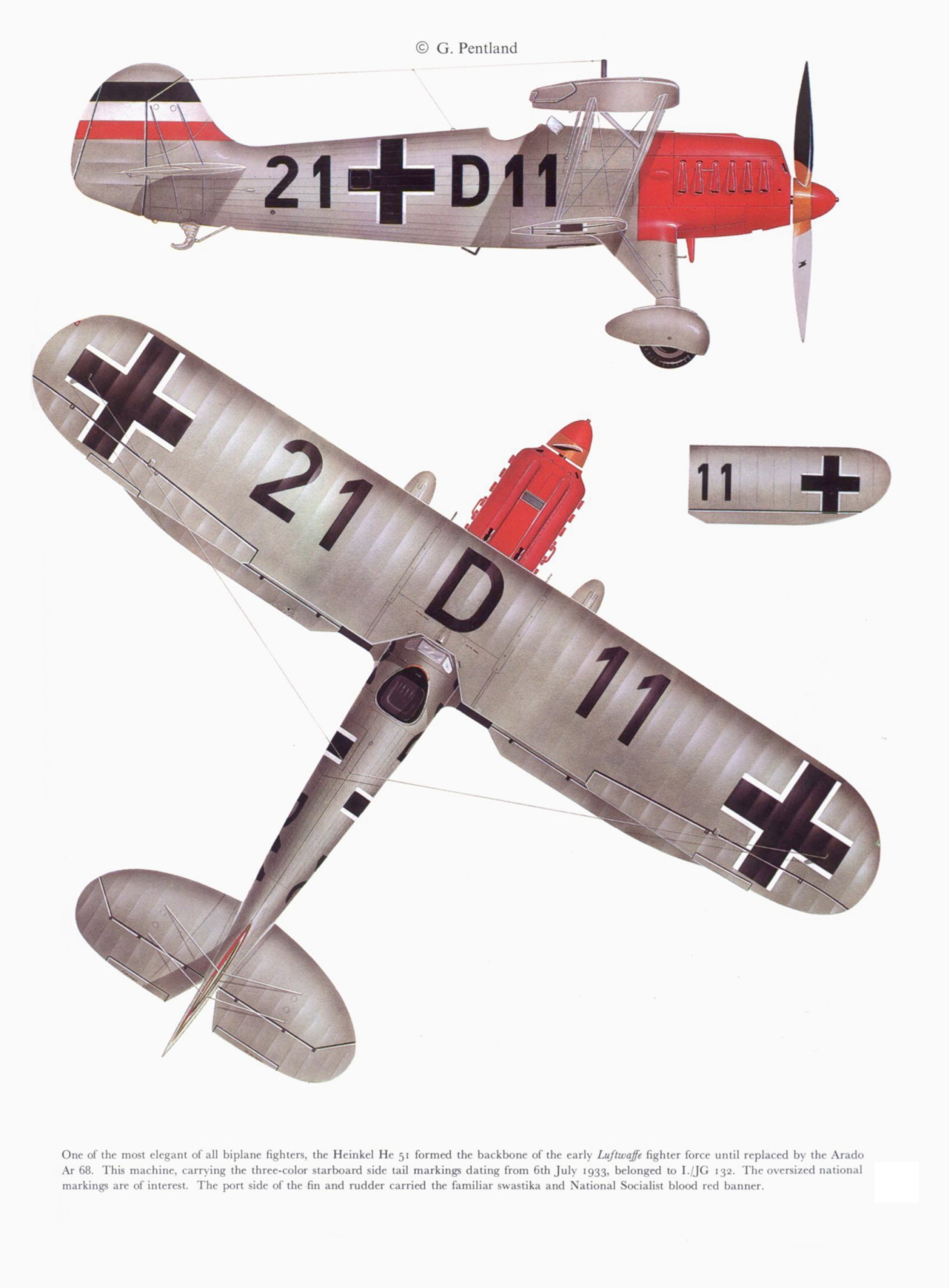

In addition to these weaknesses in personnel, which were in the final analysis unavoidable, the material build-up also led to enormous problems. As a result of discussions in the ministry of aviation and with the other two Wehrmacht services, Milch’s initial ideas of May 1933 assumed a form sufficiently concrete to make it possible to lay down the programme for the first organization period, 1934, in a directive of 12 July 1933. According to this programme a total of twenty-six squadrons were to be created as unit formations after 1 July 1934, but they were to be aligned with institutions of civil aviation ‘to preserve secrecy as far as possible’. The ten planned bomber squadrons, which were to be supported by seven reconnaissance and seven fighter squadrons, were the centre of the programme. Six weeks later, on 28 August, Milch signed the programme for the second build-up period, 1935. This programme envisaged the creation by 1 October 1935 of an additional twenty-nine squadrons as combat formations, of which seventeen were described as bomber squadrons, with only eight reconnaissance and four fighter squadrons. The number of aircraft delivered by the end of 1934 shows that the industry fulfilled its obligations according to the programme. At the end of 1934 the air units disposed of 270 bombers, ninety-nine single-seat fighters, and 303 reconnaissance aircraft; a much larger number, about 1,300 aircraft, were used for training and other purposes.