The ambush site was an excellent choice, and the deployment of the Tories and Indians was equally well adapted to the terrain. The spot selected was about six miles east of Fort Stanwix, where the military road on which Herkimer’s column was marching crossed a deep ravine about 700 feet wide and 50 feet deep. The summer rains had made the ravine passable only on the log causeway. The forest of beech, birch, maple, and hemlock provided a dark shade for the thick undergrowth which came within a few feet of the road. To make the picture complete, according to Hoffman Nickerson, “when the middle of the advancing column was down in the ravine [it would be impossible] for either the van or the rear to see what was going on” (The Turning Point of the Revolution).

The deployment of the ambushing force was as practical as it was classical. Its form might be seen as the sleeve of an inverted bayonet scabbard. The top—the closed end—was astride the road on the west side of the ravine; there the Tory troops provided the blocking force whose opening fires would smash the head of Herkimer’s column and thus bring the whole to a halt. The Indians were disposed along the sides of the sleeve to attack the flanks of the column and, of equal importance, to close around the end of the rear guard and thus complete an encirclement so that the fire of the entire ambushing forces converged on their entrapped enemy. To open the action, the bottom end of the sleeve was left open to allow the advancing column to enter and proceed until its head would be abruptly halted by the first volley.

Herkimer, Cox, and the whole column marched unhesitatingly into the trap. (What may have happened to the security elements supposedly protecting the column remains an unknown factor.) Tories and Indians lying hidden in the undergrowth listened to the militiamen of Cox’s regiment as they stumbled across the causeway and filed up the western slope of the ravine. The August heat was growing in intensity under the interlaced branches and thick leaves of the trees. Many of the farmer-soldiers fell out of the column to get a hasty drink from the shallow brook while dipping the cool water in their hats to splash over their flushed faces.

While the first oxcarts were getting closer to the causeway, Ebenezer Cox had crossed the little spur that made up the west side of the ravine and was riding toward the shallower depression beyond it. As his horse started up the slope, he heard the shrill blasts of a silver whistle sounding three times. They were the last sounds Cox ever heard. The volley from the Tory muskets crashed out of the brush, tearing into the militia’s vanguard with fearful effect and dashing Cox from the saddle, dead before he hit the ground.

A few yards behind Cox, Herkimer heard an even greater roar of firing to his rear. Could it be that his whole column was already falling victim to this ambush? He had wheeled and started toward the rear when a bullet felled his horse. At the same time Herkimer took a bullet in his leg, shattering the bone beneath the knee. The Indians on the east side of the ambush broke from their cover, unable to resist the hope of scalps to be taken and oxen to be slaughtered. They swept forward, whooping their war cries, brandishing tomahawks, spears, and scalping knives to fall upon the wagon train and the rear guard. Their headlong rush became a torrent of war-painted bodies that poured around the oxcarts and directed itself upon the terror-stricken rear guard. The best of the Tory eyewitnesses, Colonel John Butler, saw not only the premature attack but its results:

The causeway was already hopelessly choked with their unwieldy wagons, when the eagerness of some drunken Indians precipitated the attack and saved the rearguard from the fate that overtook the rest of the column. The first deliberate volley that burst upon them from a distance of a very few yards was terribly destructive. Elated by the sight, and maddened by the smell of blood and gunpowder, many of the Indians rushed from their coverts to complete the victory with spear and hatchet. The rearguard promptly ran away in a wild panic.

Despite what Butler wrote, the rear guard did not save itself. Except for a few units such as Captain Gardenier’s, Colonel Visscher’s regiment took off at a dead run, pursued by whooping Indians. The flight became a massacre. Skeletons were later found as far back as the mouth of Oriskany Creek, over two miles from the battlefield.

A look into the ravine after the smoke of the initial volleys had settled must have been like a glimpse into hell itself. Unwounded men had fallen to the ground as though struck by the same blasts of fire that had killed or wounded men all around them. After the first shock, however, militiamen knelt or propped muskets across the bodies of the dead to return the fire. At first, they could only fire back at flashes from the underbrush or even at the yells of their enemies when they moved behind cover. Soon a ragged line formed, extending from the head of the shattered wagon train, along the road up the slope from the causeway, and ending where Cox’s surviving men hugged the dirt to form an inadvertent spearhead facing the Tories at the west end of the ambush.

It was not an organized movement; it was instinctive action alone that made these frontier Americans seek cover and comradeship as they tried to fight back. They rallied along the road, and the line eventually became a series of small circles of men taking cover behind trees. The tight little circles gradually moved up the slope until they formed a rough semicircle on the higher ground between the two ravines. Fighting back was the only way to survive. Retreat into the hell of the ravine would mean certain death by musket or tomahawk.

The ambush was now becoming a pitched battle. Pressure on the main body was relieved by the departure of the mass of Indians, who were intent on pursuing the rear guard. Herkimer’s men were therefore able to fall back fighting. One must admire the toughness of seemingly undisciplined frontier militia to rally on their own until their officers could bring order out of chaos.

From the outset, leadership came right from the top. When Herkimer was pulled away from his dead horse, he was carried to high ground. There he ordered his saddle brought up and placed against a large beech tree somewhere near the center of his encircled command. Seated on his saddle, with his wounded leg stretched out before him, he maintained control. To set an example, he coolly took out his pipe, lit it, and continued to puff away as he gave his orders. One of those orders, which was to prove a decisive factor, pertained to individual tactics. Herkimer observed that an Indian would wait until an American had fired, then dash in for the kill with the tomahawk before his victim could reload his musket. He ordered the men to be paired off behind trees so that one would be ready to fire while his partner was reloading. The simple tactic paid off demonstrably; the Indians’ dashes declined markedly.

The slackening of the Indians’ fire, however, did little at first to reduce the fierceness of the hand-to-hand fighting that occurred where enemies closed in personal combat. Bayonets and clubbing muskets took their toll again and again as former neighbors, Tories and Patriots, found themselves face to face. In about an hour, however, this deadly combat was brought to an abrupt halt. By 11:00 A.M. black thunderheads had arrived overhead, and soon peals of thunder and lightning flashes swept across the forest, followed by a torrential downpour. The rain prevented keeping priming dry enough for firing, and the guns fell silent as suddenly as the firing had begun.

The rain continued to beat down for another hour. Herkimer and his officers took advantage of the summer storm to tighten up their perimeter. Then a strange distraction appeared. A solid column of men in oddly colored uniforms—at a distance they appeared to be wearing graybuff jackets and an odd assortment of hats—came marching down the road from the direction of Fort Stanwix, aligned like regular troops. A ragged cheer went up from Herkimer’s men: they must be a battalion of Continentals making a sortie from the fort!

As the column drew nearer, Captain Jacob Gardenier (whose company of Visscher’s rear-guard regiment had stayed to fight with the main body) took a second look, and barked out to his men: “They’re Tories, open fire!” The men heard him, but none obeyed. One militiaman even dashed forward to greet a “friend” in the front rank and was immediately yanked into the formation and made prisoner. Gardenier sprang forward, spontoon in hand, to lead a charge against this new enemy. And enemies they were indeed—a detachment of the Royal Greens under Major Stephen Watts, the young brother-in-law of Sir John Johnson. The Tories had turned their green jackets inside out in an almost successful trick to deceive the militiamen into holding their fire.

Gardenier plunged into the Tory formation, thrusting about him with his spontoon until he had freed the prisoner. Three of his nearest enemies recovered enough to attack Gardenier with their bayonets, pinning him to the ground by a bayonet in the calf of each leg. The third Tory thrust his bayonet against his chest, but the rugged Gardenier, a blacksmith, parried it with his bare hand, pulled his attacker down on top of him, and held him as a shield. One of Gardenier’s men jumped in to help his captain and managed to clear enough room for him to regain his feet. Gardenier, by now berserk in his battle fury, jumped up, grabbed his spontoon, and plunged it into the man he had been holding. The wounded Tory was recognized by some of the militia as Lieutenant Angus MacDonald, one of the despised Highlanders who had served as one of Sir John Johnson’s close subordinates.

In spite of the deadly scuffle going on right in front of them, the militiamen still hesitated, but only until the enraged Gardenier was back among them, roaring out his command to fire. This time the militia obeyed, and thirty of the Royal Greens went down at the first volley. Then began the most savage fighting of the fiercest frontier battle of the war. The pitch of ferocity that mounted in both sides has been told best by the novelist Walter D. Edmonds, who lived and did his research in the Mohawk Valley: “Men fired and flung their muskets down and went for each other with their hands. The American flanks turned in, leaving the Indians where they were. The woods were filled suddenly with men swaying together, clubbing rifle barrels, swinging hatchets, yelling like the Indians themselves. There were no shots. Even the yelling stopped after the first joining of the lines, and men begun to go down” (Drums along the Mohawk).

Such bloodthirstiness could not sustain itself, and finally unwounded men began to pull back to reform the lines they had left before the bloodbath. They left between them heaps of the dead, some still clutching hatchet or musket, others lying face-up where they had fallen. For a while there was intermittent sniping, but it seemed mostly to come from the muskets of the white men. The Indians had fallen strangely silent. The restless lull in the firing was broken by new sounds, at first thought to be another rainstorm. But it was soon recognized for what it was: the booming of a cannon shot, followed by a second and a third. Demooth had gotten through to the fort and there was going to be a sortie!

In the meantime, Indian runners had brought word to their fellow warriors that their camps had been attacked by the Americans in the fort and were being ransacked. It was too much for Brant’s Indians. They had never intended, and had never been trained, to fight a pitched battle. Where were the British? The Iroquois had lost many warriors—and for what? There were no dead to be looted or scalps to be taken here under the deadly fire of American muskets. So, in spite of the pleas of Butler and his officers, Brant made the decision to slip away back to the camps where his warriors might still retrieve some necessities for survival. The mournful cry “oonah, oonah” sounded back and forth through the forest, and the militiamen realized that the Indians were retreating, disappearing silently through the underbrush. They were soon followed by the Tories, who needed no convincing that without their Indian allies they would be outnumbered by Herkimer’s men, who still thirsted for revenge.

The woods were soon emptied of the enemy, all except three Iroquois who, not as easily discouraged as their brothers, had remained hidden until they could loot and scalp when the militiamen left. They were discovered, and in a last desperate rush made for Herkimer himself. The three were shot down as they dashed in, one falling almost at the general’s feet.

It was all over, all except the tragic counting of the living, the dead, and the wounded. There was no accounting for the missing. The exhausted survivors had neither the strength nor the time to search for them. They came to pick up Honnikol, who was still seated with his back to his tree, still smoking his pipe and nursing his wounded leg with its red bandanna bandage. But first they had to hear his decision. It was not easy, yet it was obvious: The militia were in no condition to take on the redcoats at the fort; there were fifty wounded to be carried, and only a hundred or more left who could march. Herkimer ordered the march to begin homeward, and a detachment was sent ahead to arrange for boats to come up the Mohawk and pick up the wounded at the nearest ford.

The actual losses on both sides were never accurately totaled. A reasonable estimate has it that of the 800 militiamen who had set out from Fort Dayton on 4 August, “all but 150 of Herkimer’s men had been killed, wounded or captured—counting out those of the rearguard who fled” (Scott, Fort Stanwix and Oriskany). As for the Tory and Indian losses, probably 150 had fallen.

The sortie that Gansevoort had ordered, a somewhat limited effort, was made by Willett with 250 men and a fieldpiece. It was they who had attacked the Tory and Indian camps and systematically looted them, carrying off twenty-one wagon loads of everything movable—weapons, ammunition, blankets, clothing, and all sorts of supplies. Willett was careful to strip the Indian camps of all cooking utensils, packs, and blankets, an act which went far to stir a seething discontent between the Indians and their British masters. Willett withdrew before a British counterstroke could cut him off from the fort, getting all of his loaded-down wagons through the gate without the loss of a single man.

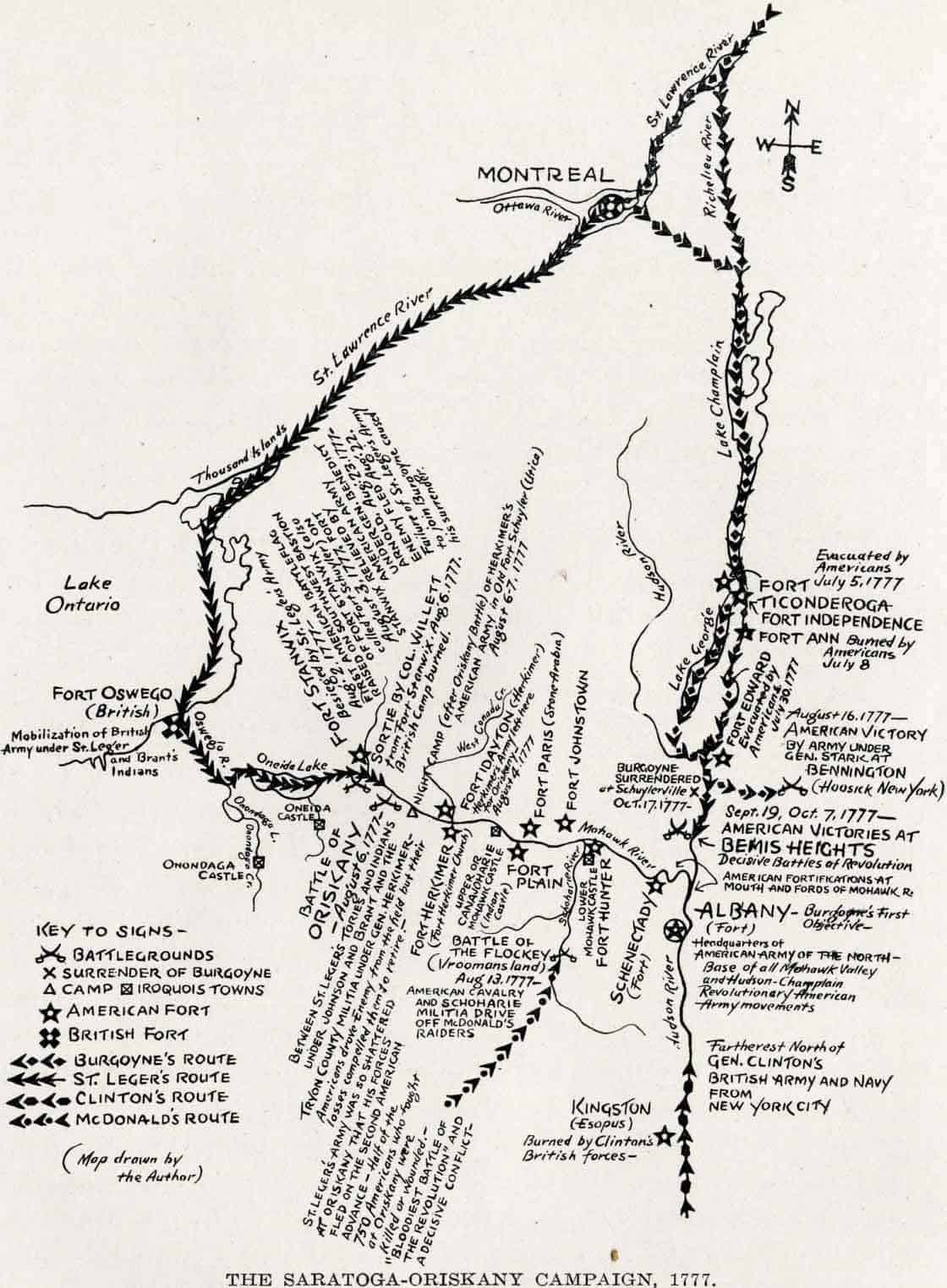

Three days later, Willett performed another feat. He crept out of the fort at 1:00 A.M. and made his hazardous and painful way through swamps and wilderness to General Schuyler at Stillwater. The general was brought up to date on the siege of Stanwix and the results of Oriskany. As Schuyler believed that St. Leger was making a methodical siege of the fort, he selected Benedict Arnold to lead an expedition to relieve it. Arnold, a major general, had eagerly volunteered to do the job, which would ordinarily have gone to a brigadier general.

Arnold left with several hundred volunteers from New York and Massachusetts regiments. By the time he had left Fort Dayton, he had picked up enough reinforcements to bring his total to about 950. Since St. Leger reportedly had about 1,700, even the intrepid Arnold had to pause and consider the odds. As he pondered, a subordinate came up with a stratagem that Arnold heartily approved. A Mohawk Valley German named Hon Yost Schuyler was respected and honored by the Indians, though considered a half-wit by the whites. At the time Schuyler was under sentence of death for trying to raise recruits for the British, so Arnold’s offer of a pardon was appealing. Hon Yost was to go to the Indians with St. Leger and spread stories of Arnold advancing to attack them with an army of thousands.

Hon Yost was a cunning rascal when he wanted to be. He propped up his coat and shot it through several times. Then, with an Oneida as his accomplice, he entered a camp near Stanwix, going in alone at first, to relate a marvelous tale of his escape from Fort Dayton, exhibiting the holes in his coat as evidence. The Indians were dismayed to hear of thousands of Americans led by Arnold, the most feared name on the frontier.

Hon Yost was finally brought before St. Leger, in whose presence he added to his story by relating how he had managed to escape on his very way to the gallows. In the meantime the Oneida had passed among the camps to warn his brother Iroquois of their imminent danger: Arnold’s force had now grown to 3,000 men, all sworn to follow their legendary leader in a campaign of revenge and massacre.

St. Leger’s Indians, already disgusted with Oriskany and its aftermath, were quick to pack up what few belongings they had left and rally around for an immediate departure. The efforts of St. Leger and his officers to placate them and persuade them to stay were words lost on the wind. As the Indians gathered to leave, they became more disorderly. They began to loot the tents of officers and soldiers, making off with clothing and personal belongings, and seizing liquor and drinking it on the spot. St. Leger reported the rioters as “more formidable than the enemy.”

Without his Indians, St. Leger now had to give in to pressures to leave, and his whole force took off for the boats at Wood Creek, taking only what they could carry on their backs. They left behind them tents as well as most of St. Leger’s artillery and stores.

Arnold arrived at Fort Stanwix on the evening of 23 August, saluted by the cheers of the garrison and a salvo of artillery. The next morning he dispatched a detachment to pursue St. Leger. Its advance elements reached Lake Oneida in time to watch the enemy’s boats disappear down the lake. Arnold left Stanwix with a garrison of 700 men, and marched with the other 1,200 to rejoin the main army at Saratoga.

The question of whether Oriskany was a victory or defeat for the Patriots cannot be answered by looking down the narrow vista provided by the battlefield. In one sense Oriskany was a defeat, simply because the battle prevented Herkimer from accomplishing his mission of relieving Fort Stanwix. Even more seriously, Tryon County had been dealt a severe blow because its staggering casualties left the Mohawk Valley virtually defenseless in terms of its own militia protecting it. In another sense, the battle was a victory for Herkimer and his cause. Not only had his militia fought its way out of an ambush, it had beaten the enemy on the field of battle, and at battle’s end remained masters of the battlefield.

In the long run, the consequences of Oriskany made possible the eventual relief of Fort Stanwix on 23 August. Moreover, the battle was a strategic success, for St. Leger had been forced to retreat all the way back to his starting point in Canada. Now there would be no one to don the dress uniforms of St. Leger’s officers that were being carried in Burgoyne’s baggage train, and no one would be coming out of the west to join and reinforce Burgoyne in his fateful advance southward.