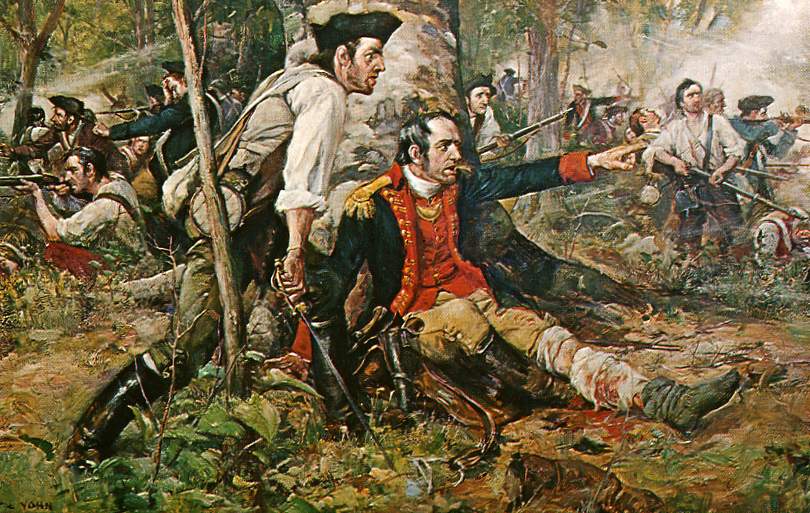

Herkimer at the Battle of Oriskany Painting by Frederick Coffay Yohn, c. 1901.

Brigadier General Nicholas Herkimer had watched his four Tryon County militia regiments take what seemed an interminable time to shuffle into an awkward column, preparatory to moving out of Fort Dayton, and the diminutive, swarthy New York militia general, age forty-nine, was feeling testy that Monday morning, 4 August 1777. Moreover, it seemed as if he himself was the only officer aware of the urgency to move this 800-man force to the aid of the small American garrison at Fort Stanwix, a good two-day’s march to the west. The enemy, in fact, could already be laying siege to it. As the train of creaking oxcarts lumbered to its place in the column, Herkimer mounted his old white horse and rode toward the head of the column. This obscure New York militia general was destined to play a critical role in an operation that would affect the outcome of the American Revolution in the northern theater.

The operation in which Herkimer’s militia was about to take part had been initiated by Major General John Burgoyne’s offensive, launched out of Canada in mid-June of that year. Burgoyne’s plan was based on a two-pronged operation that was designed to secure control of the Hudson River and split the northern colonies by preventing the movement of American troops and supplies either to north or south while assuring future British freedom of movement toward New England or, conversely, toward the Middle Atlantic colonies. Hence Burgoyne’s primary objective was Albany, New York, where the main column of his offensive was headed in late June. The other column, under Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger, was to move by way of the Saint Lawrence River to Oswego on Lake Ontario, and with the assistance of Iroquois Indians and Tories, capture Fort Stanwix and move down the Mohawk Valley to Albany, where he would link up with Burgoyne.

On 5 July Burgoyne’s main force had captured Fort Ticonderoga, and by 29 July British advance elements had reached Fort Edward and Fort George. At this point, however, the expedition of Barry St. Leger is the focus of our attention.

St. Leger’s operation is usually referred to as a diversionary effort. It was intended to be more than that; it was intended to serve political ends as well as military. The Mohawk River valley formed the central terrain feature of what was then Tryon County, whose expanse extended almost from Schenectady to the west and northwest as far as Canada and Lake Ontario. Its inhabitants came from a half-dozen regions of western Europe—English, Irish, Scotch-Irish, Germans, Netherlands Dutch, and Highland Scots.

The area was a hotbed of Toryism centered on a Tory stronghold—Sir William Johnson’s Johnson Hall. Sir William had acquired vast holdings in and around the Mohawk Valley, and his growing influence with the Indians, particularly the Iroquois, made his name familiar to Indians and settlers as far away as Ohio and Florida. He had died on the eve of the Revolution in 1774, leaving his son-in-law, Colonel Guy Johnson, as superintendent of Indian affairs, and his son, Sir John Johnson, as his heir and titular head of the family.

Guy Johnson had performed his inherited task well and had kept many Indians loyal to the Crown. But shortly after the Council of Oswego (1775), after persuading most of the Six Nations to confirm their alliance with the British, he had left for Canada, taking with him the Indian chief Joseph Brant. Sir John Johnson later followed him. It was the wish to restore this Tory hegemony—and to take vengeance upon the colonists—that persuaded the Tories of the region to band together under John Johnson to serve with St. Leger.

St. Leger was a soldier with over twenty years of active service, whose leadership qualities had been demonstrated in the French and Indian War under Abercromby, Wolfe, and Amherst. In 1777 he was forty years of age, holding the permanent grade of lieutenant colonel in the 34th Foot. Upon his assignment to command this expedition he was appointed temporary brigadier general.

His expeditionary force was an assortment of British regulars, Hessian jägers, Royal Artillerymen, Tory rangers, Tory light infantry, Canadian irregulars (including axmen), and about a thousand Indians under Joseph Brant:

Detachment from 34th Foot

100

Detachment from 8th Foot

100

Detachment, Hesse-Hanau Jagers

100

Sir John Johnson’s Royal Greens

133

Colonel John Butler’s Loyalist Rangers

127

Canandian militia (including axmen)

535

Artillery crews for two six-pounders, two three-pounders, and four mortars

40

Joseph Brant’s Indians

1,000

Total rank and file

2,135

The force totaled over 2,000 men when it was finally assembled at Oswego, the rendezvous where St. Leger was joined by Brant on 25 July. On the following day he commenced his march toward Fort Stanwix. Although the fort had been built to guard the western passages to and from the Mohawk Valley, St. Leger believed it to be a crumbling and easily reducible ruin.

Nearly half of St. Leger’s force—1,000 men out of 2,135—were Indians under the leadership of Chief Joseph Brant. Brant could be a figure cast in a heroic mold or a monster in half-human form, depending on the viewpoint of Indian and Briton or that of the Patriot settler exposed to frontier warfare. Son of a Mohawk warrior and an Indian mother, he became known as Brant when his mother remarried after his father’s death, but to the Iroquois he was always Thayendanegea, their warrior-leader. Brant was no ordinary savage. After serving under Sir William Johnson in his Lake George campaign, he had studied English at Lebanon, Connecticut, and had later led Iroquois warriors loyal to the British in Pontiac’s Rebellion. As Guy Johnson’s secretary, Brant had been presented at court in London and was so socially celebrated that his portrait was painted by Romney. After his return to America he led tribesmen during the British-Canadian victory over the Americans at The Cedars in May 1776. In July 1777 he joined St. Leger at Oswego, ready to march with the British leader on Fort Stanwix.

Fort Stanwix, erected in 1758 during the French and Indian War, was strategically located to command not only the Mohawk River but also the portages linking the river with the waterways flowing into Lake Ontario. As long as it was adequately garrisoned, it clearly dominated the Mohawk Valley, but by 1777 it had been long abandoned. In April of that year it was occupied once more by twenty-eight-year-old Colonel Peter Gansevoort and his 550 New York Continentals. Though he declared the fort “indefensible and untenable,” Gansevoort set his regiment to work against time to restore the fort. He and his capable second in command, Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willett, pushed the men until the works might withstand attack or siege, just in the nick of time to take on St. Leger’s advancing army.

But though Fort Stanwix was being prepared for battle, news from Canada, magnified by the constant threat of Indian raids, brought about “a general paralysis” among the people of the valley. In that atmosphere they turned to Nicholas Herkimer. Accordingly, on 17 July 1777 Herkimer distributed copies of a ringing proclamation calling on “every male person, being in health, from 16 to 60 years of age, to repair immediately, with arms and accoutrements, to the place to be appointed in my orders.” From there they would “march to oppose the enemy with vigor, as true patriots, for the just defense of their country.” The proclamation produced the desired effect. The Patriot settlers placed their trust in Honnikol—as his German Flats neighbors called their neighbor. They were ready to rally at his call.

St. Leger’s force was skillfully deployed on the march. Brant’s Indians moved as a screening force, covering advance elements of the main body as well as both flanks of the force. The main body was composed of the rest of the Tory units and the British regulars marching in two parallel detachments. As a whole, the force managed a march rate of ten miles a day, no mean accomplishment in such rough wilderness terrain.

On 3 August St. Leger arrived outside Fort Stanwix and attempted to bluff the garrison into surrender. First, he assembled his whole force to pass in review—at a safe distance—under the eyes of the garrison, a display as colorful as it was arrogant. The scarlet of the British 8th and 34th regiments contrasted with the blue of the German regulars, who were followed by the green of the Tory units. The nonuniformed Indians, in war paint and shouting their battle cries, completed the review. Instead of being awed by the whooping savages, the American soldiers were forcefully reminded of the fate that would be theirs if they fell into the hands of Indian torturers, not to mention what would happen to the settlers of the valley the fort’s garrison was there to protect. Two days later St. Leger sent a written threat to Gansevoort threatening dire consequences for his resistance. Gansevoort returned the document with his refusal to surrender.

He soon recognized that the restored fortifications could not be taken by storm, and St. Leger then disposed his army for a siege. The besieging forces took up three main positions, roughly making up the sides of a triangle. The regulars occupied the position north of the fort; Tories, Canadians, and Indians stretched along the so-called Lower Landing to positions west of the fort. Finally, Indians were also posted on the east bank of the Mohawk across from the Lower Landing.

With the fort thus surrounded on three sides, St. Leger’s force occupied itself clearing a passage for his supply and artillery bateaux and exchanging sniper fire with the garrison through 4 and 5 August.

On the evening of the fifth St. Leger received a message that was to change his plans for continuing the siege. Joseph Brant’s sister Molly, who had remained behind, had dispatched a runner to inform St. Leger that an American column was on its way to relieve Gansevoort. By the time that St. Leger received the message, the Americans could be within a few miles of the fort.

Having left Fort Dayton in German Flats on the morning of 4 August, Herkimer’s column of 800 Tryon County militia encamped that evening near Starring Creek, about twelve miles to the west. On the following day Herkimer’s column crossed to the south bank of the Mohawk and later halted on the night of 5-6 August to encamp along the road to Fort Stanwix, in the vicinity of present-day Whitesboro. The head of the column was about eight miles from the fort, between Sauquoit and Oriskany creeks.

On the march, the temper of Herkimer’s men had been changing rapidly from mild resolve to grim determination. Their regimental commanders, Colonels Jacob Klock, Ebenezer Cox, Peter Bellinger, and Richard Visscher, had fanned these fires. Now, at nightfall on the fifth, with their campfires making islands of yellow light against the blackness of the hemlocks and beeches, they were spoiling for a fight.

Herkimer, despite his reputation for a phlegmatic temperament, was worried. There were too many unknowns to ponder. Particularly he was concerned about what both Gansevoort and St. Leger knew, and what their reactions would be when they received word of his column’s strength and whereabouts. Would St. Leger dispatch a force to intercept him? Would Gansevoort launch a sortie against St. Leger to distract the British commander from intercepting the relief column?

Herkimer dispatched Captain John Demooth and several men to find their way through to the fort and tell Gansevoort to acknowledge Demooth’s message (and his willingness to make a sortie) by the firing of three cannon shots.

Herkimer’s concern was eased somewhat by the arrival of sixty friendly Oneidas under Chiefs Honyerry and Cornelius, who agreed to employ their warriors as scouts on the march to Fort Stanwix. But the danger of ambush remained. Herkimer’s problem was exacerbated by the rashness of his senior officers. In a council of war the next morning the four regimental commanders, their bright blue and buff uniform coats contrasting with the brown of Herkimer’s, urged immediate action. Colonel Ebenezer Cox, in fact, set the tenor by abruptly demanding marching orders from Honnikol before the little brigadier had time to make a formal opening of the council. Herkimer replied by recounting his dispatching of Captain Demooth and his men during the night, as well as his request of Gansevoort for a sortie to be acknowledged by three cannon shots. It was still early morning and there had been no cannon shots. After all, Demooth had to be given reasonable time to get through to the fort.

The explanation, while sensible, didn’t suffice to keep the colonels quiet. Though Herkimer, a veteran of the French and Indian War, probably reminded the council of Braddock’s ambush and defeat less than a generation before, the argument went on for almost an hour. Meanwhile, a gaping throng of militiamen left their breakfast cooking fires to crowd around and listen to the fascinating sounds of growing discord among the higher-ups.

The challenges to Herkimer’s caution eventually became taunts of disloyalty and even of cowardice. Though reminded pointedly that at least one member of his family was marching with St. Leger’s Tories—a low blow—Herkimer managed to sit quietly, smoking his pipe and listening for cannon shots that never came.

Finally he gave way. He knocked out his pipe, reminded his accusers that “burning, as they now seemed[,] to meet the enemy . . . [they would] run at his first appearance,” and dismissed the council by mounting his horse and giving the order to march on. His words “were no sooner heard than the troops gave a shout, and moved, or, rather, rushed forward.”

Thus the march began, four itchy regiments led—with the exception of Herkimer—by impetuous men who had cast aside what little they knew about forest warfare. They marched in double column, a file in each rut: Cox leading off, followed by Jacob Klock, then Peter Bellinger, and finally Richard Visscher. The Oneidas were out somewhere to the front, out of contact, as were the company of rangers who were supposed to have been acting as scouts and flank guards.

About 9:00 A.M. the head of the column, with Herkimer and Cox riding in the lead, was approaching the wide and deep ravine made by the little stream that would become known as Battle Brook. Without hesitating, Cox put his horse down the steep eastern side of the ravine, crossed the corduroy causeway, and led the way up the more gentle slope on the western side.

While Herkimer’s men were still preparing to halt for the night of 5-6 August, St. Leger had received Molly Brant’s timely message and had decided to take the action he later described in his report: “I did not think it prudent to wait for them [Herkimer’s men], and thereby subject myself to be attacked by a sally from the garrison in the rear, while the reinforcement employed me in front. I therefore determined to attack them on the march, either openly or covertly, as circumstances should offer.”

As it turned out, the circumstances did offer an ideal opportunity for an ambush, the most reliable tactic that St. Leger’s provincial officers could use to employ the Indians to best advantage. So St. Leger dispatched a detachment of the Royal Greens, Tory rangers, and perhaps half of the Indians (about 400) under Sir John Johnson. (The British regulars were noticeably missing.) The total strength of the force came to about 500.