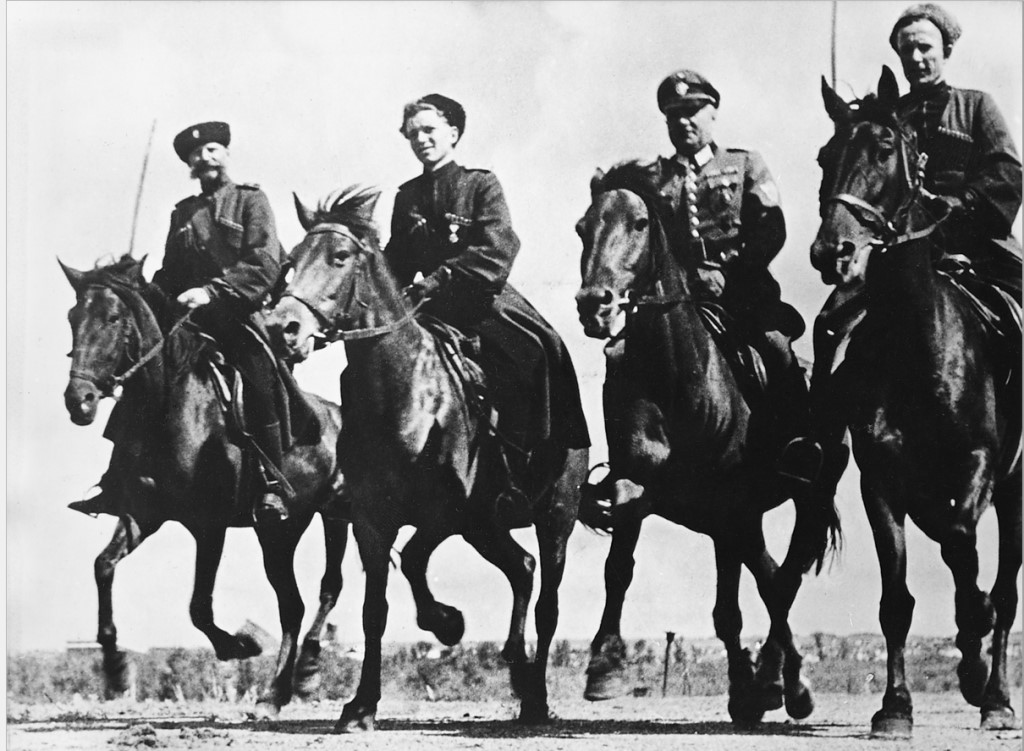

A group of cavalrymen from the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division. This unit was formed in 1943 from prisoners of war and the various ad hoc formations of Cossack deserters that had been gathered by Wehrmacht field commanders. It also included men recruited from the short lived autonomous “Cossack District” that was located in the Kuban region south of Rostov-on-Don.

Contrary to popular legend, and despite anti-communist sentiments nourished by many Cossacks and the cracking-down on many aspects of Cossack traditions by the communist regime, the overwhelming majority of Cossacks remained loyal to the Soviet Government. That said, substantial numbers of Cossacks did fight for the Germans in World War II.

On 22 August 1941, while covering the retreat of Red Army units in eastern Belarus, a Don Cossack major in the Red Army named Kononov (a graduate of Frunze Military Academy, veteran of the Winter War against Finland, a Communist Party member since 1927 and holder of the Order of the Red Banner) deserted and went over to the Germans with his entire regiment (the 436th Infantry Regiment of the 155th Soviet Infantry Division), after convincing his regiment of the necessity of overthrowing Stalinism (among the few incidences of a whole Soviet regiment going over to the Axis during World War II). He was permitted by local German commanders to establish a squadron of Cossack troopers composed of deserters and volunteers from among POWs, to be used for frontline raiding and reconnaissance missions. With encouragement from his new superior, General Schenkendorff, eight days after his defection Kononov visited a POW camp in Mogilev in eastern Belarus. The visit yielded more than 4000 volunteers in response to the promise of liberation from Stalin’s oppression with the aid of their German “allies”. However, only 500 of them (80 percent of whom were Cossacks) were actually drafted into the renegade formation. Afterwards, Kononov paid similar visits to POW camps in Bobruisk, Orsha, Smolensk, Propoisk and Gomel with similar results. The Germans appointed a Wehrmacht lieutenant named Count Rittberg to be the unit’s liaison officer, in which capacity he served for the remainder of the war.

By 19 September 1941, the Cossack regiment contained 77 officers and 1799 men (of whom 60 percent were Cossacks, mostly Don Cossacks). It received the designation 120th Don Cossack Regiment; and, on 27 January 1943, it was renamed the 600th Don Cossack Battalion, despite the fact that its numerical strength stood at about 2000 and it was scheduled to receive a further 1000 new members the following month. The new volunteers were employed in the establishment of a new special Cossack armoured unit that became known as the 17th Cossack Armoured Battalion, which after its formation was integrated into the German Third Army and was frequently employed in frontline operations.

Kononov’s Cossack unit displayed a very anti-communist character. During raids behind Soviet lines, for example, it concentrated on the extermination of Stalinist commissars and the collection of their tongues as “war trophies”. On one occasion, in the vicinity of Velikyie Luki in northwestern Russia, 120 of Kononov’s infiltrators dressed in Red Army uniforms managed to penetrate Soviet lines. They subsequently captured an entire military tribunal of five judges accompanied by 21 guards, and freed 41 soldiers who were about to be executed. They also seized valuable documents in the process.

Kononov’s unit also carried out a propaganda campaign by spreading pamphlets on and behind the frontline and using loudspeakers to get their message to Red Army soldiers, officers and civilians. Unfortunately for Kononov, the behaviour of the Germans in the occupied territories worked against his campaign. But Kononov’s Cossacks continued to serve their German “liberators” loyally, and were particularly active with Army Group South during the second half of 1942.

Aside from Kononov’s unit, in April 1942, Hitler gave his official consent for the establishment of Cossack units within the Wehrmacht, and subsequently a number of such units were soon in existence. In October 1942, General Wagner permitted the creation, under strict German control, of a small autonomous Cossack district in the Kuban, where the old Cossack customs were to be reintroduced and collective farms disbanded (a rather cynical propaganda ploy to win over the hearts and souls of the region’s Cossack population). All Cossack military formations serving in the Wehrmacht were under tight control; the majority of officers in such units were not Cossacks but Germans who had no sympathy towards Cossack aspirations for self-government and freedom.

The 1942 German offensive in southern Russia yielded more Cossack recruits. In late 1942, Cossacks of a single stanitsa (Cossack settlement) in southern Russia revolted against the Soviet administration and joined the advancing Axis forces. As the latter moved forward, Cossack fugitives and rebellious mountain tribesmen of the Caucasus openly welcomed the intruders as liberators. On the lower Don River, a renegade Don Cossack leader named Sergei Pavlov proclaimed himself an ataman (Cossack chief) and took up residence in the former home of the tsarist ataman in the town of Novoczerkassk on the lower Don. He then set about establishing a local collaborationist police force composed of either Don Cossacks or men of Cossack descent. By late 1942, he headed a regional krug (Cossack assembly) which had around 200 representatives, whom he recruited from the more prominent local collaborators. He also requested permission from the Germans to create a Cossack army to be employed in the struggle against the Bolsheviks, a request that was refused.

The Cossack Movement

The leading figures in the Cossack movement tried to bring about the creation of a Cossack nation, but were always thwarted by Nazi policy in the East. For example, a former tsarist émigré general named Krasnov, based in Berlin, with Hitler’s blessing backed the foundation (in German-occupied Prague) of a Cossack Nationalist Party. It was made up of Cossack exiles who had fled abroad after the White defeat in the Russian Civil War. Party members swore unwavering allegiance to the Führer as “Supreme Dictator of the Cossack Nation”. Simultaneously, a Central Cossack Office was established in Berlin to manage and direct the German-sponsored party. The ultimate aim was to create a “Greater Cossackia”: a Cossack-ruled German protectorate extending from eastern Ukraine in the west to the River Samara in the east.

Though the idea of a Cossack state had no part in Nazi plans, the Germans did agree to enlarge the hitherto existing autonomous Cossack district in the Kuban and to enroll additional Cossacks into the ranks of the Wehrmacht in order to placate the progressively more dissatisfied Cossacks. By the beginning of 1943, though, the Axis was retreating following the disaster at Stalingrad and thus these plans came to nought. Due to the sudden military reverses suffered by the Germans in southern Russia, many Cossack collaborators were forced to join the retreat west in order to escape reprisals from the Soviets. In February 1943, the Germans withdrew from Novoczerkassk, taking with them Ataman Pavlov and 15,000 of his Cossack followers. He temporarily re-established his headquarters at Krivoi Rog in the spring of 1943, and shortly afterwards the Wehrmacht allowed him to create his own Cossack military formation. Numerous Don, Kuban and Terek Cossacks were called to the colours, but many turned out to be so unsuitable for combat duties that they were sent to work on local farms instead.

Soon the horde of Cossack refugees was on the move again, eventually ending up at Novogrudek in western Belarus, from where five poorly equipped Cossack regiments were dispatched into the countryside to operate against Soviet and Polish partisans. By this time, much of Belarus was controlled by partisans, and the Cossacks took heavy losses with Pavlov being killed. Domanov was appointed as his immediate successor. As a result of the successful Soviet offensive in Belarus and the Baltics undertaken in the summer of 1944, codenamed Operation Bagration, the Cossack column was once again forced to retreat, this time westwards to the vicinity of Warsaw. By this period, any semblance of discipline had disappeared and the Cossacks left a trail of rape, murder and looting. From northeastern Poland they were transported across Germany to the foothills of the Italian Alps where they ended the war.

It was only when the military situation in the East had turned against them that the Germans enticed the Cossacks with promises of greater independence. For example, in mid-1943, the High Command deemed it appropriate to create a Cossack division under the leadership of Oberst Helmuth von Pannwitz. The division was formed at a recently established Cossack military camp at Mlawa in northeastern Poland from Kononov’s unit and a regiment of Cossack refugees. Following its formation, the 1st Cossack Division comprised seven regiments (two regiments of Don Cossacks, two regiments of Kuban Cossacks, one regiment of Terek Cossacks, one regiment of Siberian Cossacks and one mixed reserve regiment). As was customary, the Cossack officers were replaced by German ones, with the sole exception of the most notable Cossack commanders who retained their posts (Kononov being one of them). Nazi racial prejudices resulted in the German officers and NCOs mistreating the Cossacks, who retaliated by assaulting and even killing some of their more arrogant superiors. In September 1943, the division was transported to France to assist in the guarding of the Atlantic Wall. However, the Cossacks requested to be assigned frontline responsibilities outside France. The German High Command thus transferred the division to Yugoslavia to take part in anti-partisan operations.

By the end of 1943, the Germans had retreated from the Cossack homelands in Russia. As a result, the Cossacks in German service became disillusioned, and so, in November, Alfred Rosenberg, Nazi Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, and Chief of Staff of the OKW, Feldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel, assured the Cossacks that the German Army would retake their homelands. However, as the military situation made such promises unrealistic, arrangements were made to set up a so-called “Cossackia” outside the Cossack homelands. Eventually, the foothills of the Carnic Alps in northeastern Italy were selected for the purpose of providing the wandering Cossacks with a new home.

As Hitler’s armies advanced on Stalingrad they overran the Cossack regions of the Don, Terek and Kuban. Hundreds of thousands of Russians willingly enrolled in the German army to form a Cossack Army under the Russian General Krasnoff. Hitler promised that they would be settled in “lands and everything necessary for their livelihood in Western Europe”. Their new homeland was to be in north-east Italy in the valley of Carnia on the plain of Undine where they would live their national life free from the confines of Bolshevism.

Italian families in the area were ejected from their homes which were then used to house the Cossack soldiers and their families who had arrived in fifty trains during July and August 1944. To the Cossacks this was paradise far removed from their dreary life in the Ukraine. Hitler had named this new independent state ‘Kosakenland’. Many atrocities were committed by these Russians against the Italian civilians, particularly the women, causing one Archbishop to write to Mussolini “It is terrible to think that Friuli will be governed by these illiterate savages”. Discipline was soon restored when General Krasnoff himself arrived. Cossack officers were under no delusions, they knew they were there to shed blood for the Nazi cause. With the Allied armies approaching from the south and Tito’s IX Yugoslav Corps approaching from the east, the ‘Free Republic of Carnia’ soon disintegrated and the Cossacks and their followers forced to trundle north towards Austria and internment by the British.

The Germans determined that they would “annex” Italian territories into the Third Reich. Two new German regions were to be established. One was the Alpenvorland and it was to comprise the region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol and the Province of Belluno. The other was Adriatisches Kustenland and it was to comprise Istria, Quarnero, and most of today’s region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. In the valley of Carnia, anti-Communist forces from the Soviet Union under the command of ataman Timofey Ivanovich Domanov were used; they were promised the establishment of a Cossack republic in Northeastern Italy, to be called Kosakenland.

The Germans had a major security problem in occupied Italy although operations against partisans were not conducted by Kesselring’s formations but fell to a separate command under SS General Karl Wolff. This command deployed the equivalent of ten divisions and personnel included Italian fascists, Cossacks, Slovaks and even some Spaniards as well as Germans. Wolff’s men fought a bitter and vicious campaign against Italian partisans and committed many atrocities against civilians. One of the forgotten stories of the Second World War is that of Italian resistance to the German occupation: Italians resisted to a much greater level, and to more effect, than did the French whose story is much better known.

In March 1944, an organizational/administrative committee was appointed for the purpose of synchronizing the activities of all Cossack formations under the Third Reich’s jurisdiction. This “Directorate of Cossack Forces” included Naumenko, Pavlov (soon replaced by Domanov) and Colonel Kulakov of von Pannwitz’s Cossack Division. Krasnov was nominated as the Chief Director, who would assume the responsibilities of representing Cossack interests to the German High Command.

In June 1944, Pannwitz’s 1st Cossack Division was elevated to the status of a corps and became XV Cossack Corps, with a strength of 21,000 men. In July, the corps was formally incorporated into the Waffen-SS, which allowed it to receive better supplies of weapons and other equipment, as well as to bypass notoriously uncooperative local police and civil authorities. Interestingly, the Cossacks retained their uniforms and German Army officers.

The granting of SS status to the Cossack corps was part of Himmler’s scheme to limit the Wehrmacht’s influence over foreign formations. The Reichsführer-SS was quite happy to accept Cossacks into the SS, as Alfred Rosenberg’s ministry came up with the theory that the Cossack was not a Slav but a Germanic descended from the Ostrogoths. A replacement/training division of 15,000 men was also formed at Mochowo, southwest of Mlawa. The corps fought in Yugoslavia; and at the end of the war, 50,000 strong, retreated to Austria to surrender to the British.

In all, around 250,000 Cossacks fought for the Germans in World War II. The Germans used them to fight Soviet partisans, to undertake general rear-area duties for their armies, and occasionally for frontline combat. But they were held in scant regard by most German Army commanders.