War of the Fourth Coalition (1806-1807)

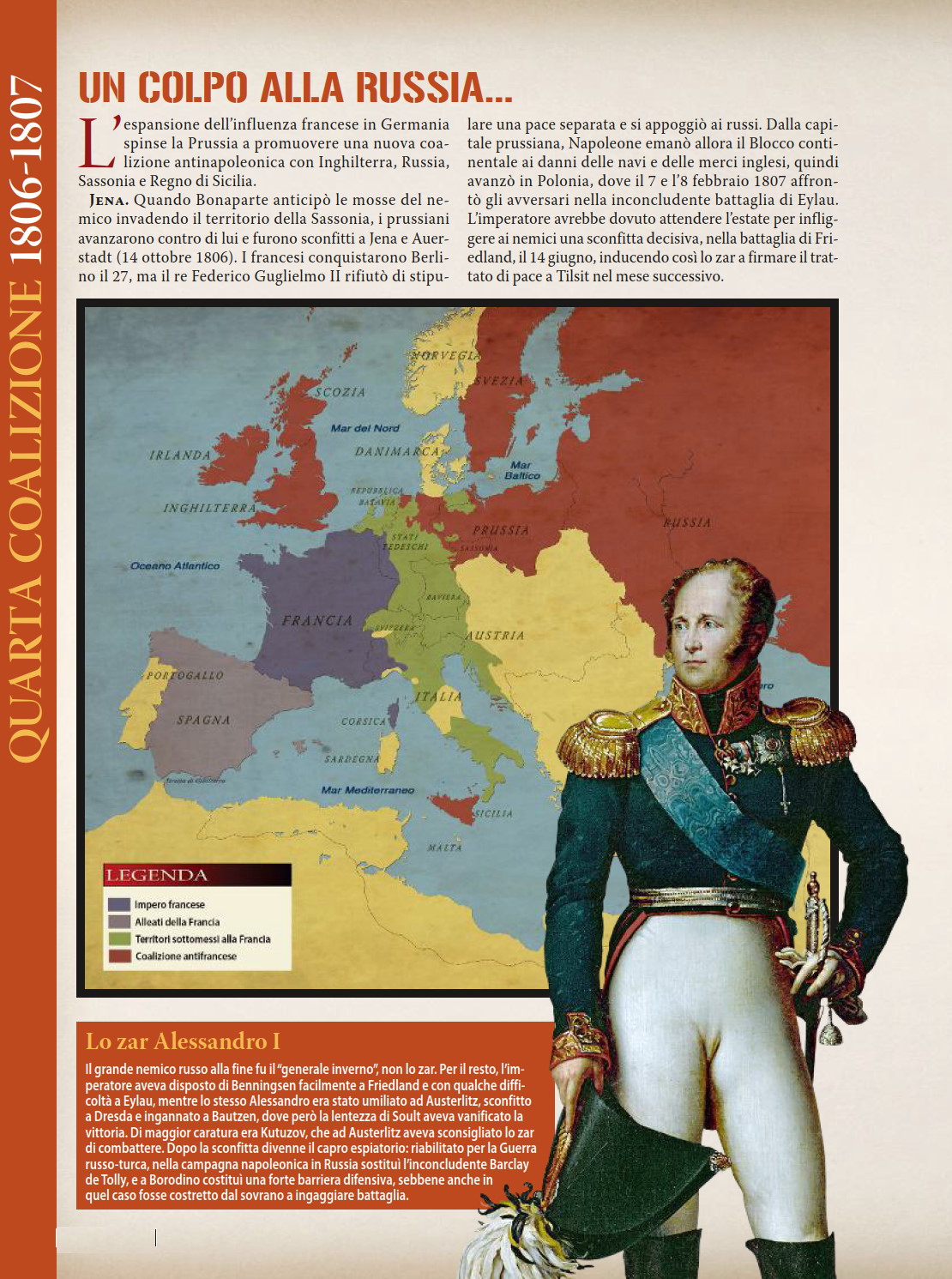

Although Austria withdrew from the coalition after Austerlitz, Britain and Russia remained at war with France. The Fourth Coalition came into being in the autumn of 1806 after a breakdown in Franco-Prussian relations, largely the result of Napoleon’s failure to cede Hanover (formerly a hereditary possession of George III) to Prussia, as promised, and of the establishment of the Confederation of the Rhine-a new political entity replacing the Holy Roman Empire (abolished in 1806) consisting of various German states all allied to, or dependent on, France. Prussia had remained neutral during the 1805 campaign-in hindsight a grave strategic error on its part-but with the growing influence of France in German affairs it threw in its lot and, together with its ally, the Electorate of Saxony, declared war.

The Grande Armée, situated in northeast Bavaria, prepared to invade Prussia; the Prussians were commanded by the Duke of Brunswick, a veteran of the wars of Frederick the Great. With remarkable speed the French began their advance on 8 October, achieving complete surprise. Marshal Lannes, in a minor action at Saalfield on 10 October, defeated a small Prussian force and killed Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, while the main French army turned the Prussian left flank while making for Berlin. Napoleon fought part of the main Prussian army under Fürst Hohenlohe (Friedrich Ludwig Fürst zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen) at Jena on 14 October. Hohenlohe’s command was, however, merely a small force meant to protect Brunswick’s rear; Napoleon’s numerical superiority predictably told, and Hohenlohe was routed. At Auerstädt, a short distance to the north, on the same day, Davout, who had been sent to cut Prussian communications, encountered the main Prussian force under Brunswick. There the odds were rather different, with Davout outnumbered by a force more than twice the size of his own. He managed to hold on, however, and when Bernadotte arrived, the tide turned decisively in the French favor, with the Prussians routed there as well, and the Duke of Brunswick mortally wounded.

The destruction of Prussia’s main army effectively spelled the end of resistance, and the remainder of the campaign consisted of the French pursuit of small contingents, virtually all of which eventually put down their arms, and the capture of fortresses. Berlin itself fell on 24 October, and the last major force to hold out, near Lübeck, surrendered a month later. A small Prussian contingent managed to make contact with the Russians in Poland, into which Napoleon immediately proceeded, taking Warsaw in an effort to prevent the Russians from assisting their vanquished allies.

Adhering to the principle that the key to victory lay in confronting and decisively defeating the main enemy force, Napoleon sought out the Russian army under General Bennigsen, the first encounter taking place on 26 December at Pultusk, where the Russians were bruised but nothing more. The rival armies went into winter quarters in January 1807 amid bitterly cold temperatures, but the campaign resumed the following month, when Bennigsen began to move and Napoleon went in pursuit. Though outnumbered and caught in a blizzard, Napoleon reached the Russians at Eylau, where on 8 February the two sides inflicted severe losses on one other with no decisive result. Bennigsen withdrew, but with appalling losses and atrocious weather, Napoleon declined to follow. Both sides returned to winter quarters to recover from the carnage, with the renewal of hostilities planned for the spring.

Bennigsen and Napoleon each planned to assume the offensive, but when Bennigsen advanced first, he was stopped at Heilsberg on 10 June. Four days later the decisive encounter of the campaign took place at Friedland, where Bennigsen foolishly placed his army with the river Alle at his back. The Russians resisted enemy attacks with magnificent stoicism, eventually collapsing. With no route of escape, the campaign was over. Tsar Alexander, his army in tatters, and accompanied at headquarters by Frederick William III of Prussia, requested a conference to discuss peace. The three sovereigns concluded the Treaty of Tilsit between 7 and 9 July, putting the seal on Napoleonic control of western Europe. Frederick William was humiliated, having given up those portions of his Polish possessions originally taken during the Partitions of Poland more than a decade before to the newly established duchy of Warsaw, a French satellite state. To the Confederation of the Rhine, Prussia ceded all its territory between the Rhine and the Elbe, most of this forming the new Kingdom of Westphalia under Napoleon’s brother, Jérome. A French army of occupation was to re- main on Prussian soil until a huge war indemnity was paid. Russia was required to enter into an alliance with France against Britain and to recognize the duchy of Warsaw. With Russia and Prussia knocked out of the war, only Britain remained to face France, now at the height of its power.

War of the Fifth Coalition (1809)

The Fifth Coalition hardly justified the name, for when Austria once again chose to oppose France, it did so without al- lies to assist it on land. Britain, of course, carried on operations at sea and offered substantial subsidies and loans as it had since 1793, but it could do little more on land than send an expedition in July to Walcheren Island, off the Dutch coast, where disease soon rendered the whole affair a disaster and obliged the British to withdraw in October. Nevertheless, the Austrians had some reason to be hopeful, for in fielding a sizable army in the spring of 1809, they took advantage of the absence from central Europe of large numbers of French troops who had been diverted to serve in operations in Spain. Yet, with misplaced optimism, they underestimated Napoleon’s ability to muster his forces and concentrate them quickly, for by the time the Habsburg armies were ready to fight, the French had shifted reinforcements from the Iberian Peninsula to meet this revived threat.

The main Austrian army under Archduke Charles invaded the principal member of the Confederation of the Rhine, Bavaria, which also had to contend with an Austrian-inspired revolt in the Tyrol, a region formerly under Habsburg control. At the same time, Archduke John crossed the Alps to invade northern Italy, repulsing Eugene de Beauharnais, the viceroy of Italy and a staunch ally of France, at Sacile on 16 April. When Napoleon arrived from Spain, he moved immediately to the offensive, crossing the Danube and defeating an Austrian force at Abensberg on 19-20 April before turning on Charles, then under observation by Davout. Charles struck first, confronting Davout at Eggmühl but failing, despite overwhelming numerical superiority, to defeat him, as a result of Napoleon’s arrival. French exhaustion from three days’ engagements (at Abensberg, Landshut, and Eggmühl) denied them the opportunity to pursue Charles, though they managed to storm and seize Ratisbon on 23 April. Three weeks later French troops occupied Vienna without a shot being fired.

Charles meanwhile concentrated his army on the north bank of the Danube. Napoleon ordered pontoon bridges constructed to span the river to Lobau Island, and then to the other side, where troops positioned themselves in the villages of Aspern and Essling. On 21-22 May the two sides fought bitterly for possession of these villages, but the French refused to be dislodged. However, with the single French bridge unable to allow substantial numbers of reinforcements to be fed to the north side of the river, Napoleon withdrew his forces to the opposite bank, marking out Aspern-Essling as the Emperor’s first defeat. Napoleon intended to recross the Danube and confront Charles for a second time, but he knew he must first develop another plan to do so. Meanwhile, on the Italian front, Archduke John was obliged to withdraw back over the Julian Alps, followed by Eugene, who was successful at Raab on 16 June and subsequently moved to link up with the main French army on the Danube.

Hoping to defeat Charles before he could be reinforced by Archduke John, Napoleon recrossed the Danube on the night of 4-5 July. The Austrians offered no resistance to the crossing, but on 5 and 6 July heavy fighting took place at Wagram, where Charles attempted to isolate Napoleon from his bridgehead. This maneuver, however, failed; the Austrian center was pierced, and Charles was obliged to re- treat, albeit with very heavy losses suffered by both sides. Austria could no longer carry on the war. Vienna was under enemy occupation, the main army had been beaten, though not destroyed, and Russia had not joined the campaign as Austria had hoped. Francis duly sued for peace on 10 July and three months later signed the Treaty of Schönbrunn, by which he relinquished large portions of his empire to France and its allies and promised to adhere to Napoleon’s Continental System, by which the Emperor sought to impose an embargo on the importation of British goods to the Continent and the exportation of continental goods to Britain in an effort to strangle its economy.

The Campaign in Germany (1813)

However immense the losses suffered by Napoleon in Russia, his extraordinary administrative skills enabled him to rebuild his army by the spring of 1813, though neither the men nor the horses could be replaced in their former quality or quantity. The Sixth Coalition, which had been formed by Britain, Russia, Spain, and Portugal in June 1812, now expanded as other states became emboldened to oppose Napoleonic hegemony in Europe. The Prussian corps, which had reluctantly accompanied the Grande Armée into Russia, declared its neutrality by the Convention of Tauroggen on 30 December 1812, and on 27 February 1813 Frederick William formally brought his country into the coalition by the terms of the Convention of Kalisch, signed with Russia. The Austrians remained neutral during the spring campaign, with Fürst Schwarzenberg’s corps, which had covered the southern flank of the French advance into Russia, withdrawing into Bohemia.

By the time the campaign began in the spring, Napoleon had created new fighting formations from the ashes of the old, calling up men who had been exempted from military service in the past, those who had been previously discharged but could be classed as generally fit, and those who, owing to their youth, would not normally have been eligible for front-line duty for at least another year. With such poorly trained and inexperienced, yet still enthusiastic, troops Napoleon occupied the Saxon capital, Dresden on 7-8 May, and defeated General Wittgenstein, first at Lützen on 2 May and again at Bautzen on 20-21 May. Both sides agreed to an armistice, which stretched from June through July and into mid-August, during which time the French recruited and trained their green army, while the Allies assembled larger and larger forces, now to include Austrians, Swedes, and troops from a number of former members of the Confederation of the Rhine.

When the campaign resumed, the Allies placed three multinational armies in the field: one under Schwarzenberg, one under Blücher, and a third under Napoleon’s former marshal, Bernadotte. The Allies formulated a new strategy, known as the Trachenberg Plan, by which they would seek to avoid direct confrontation with the main French army under Napoleon, instead concentrating their efforts against the Emperor’s subordinates, whom they would seek to defeat in turn. The plan succeeded: Bernadotte drubbed Oudinot at Grossbeeren on 23 August, and Blücher won against Macdonald at the Katzbach River three days later. Napoleon, for his part, scored a significant victory against Schwarzenberg at Dresden on 26-27 August, but the Emperor failed to pursue the Austrian commander. Shortly thereafter, General Vandamme’s corps became isolated during its pursuit of Schwarzenberg and was annihilated at Kulm on 29-30 August.

The end of French control of Germany was nearing. First, Bernadotte defeated Ney at Dennewitz on 6 September; then Bavaria, the principal member of the Confederation of the Rhine, defected to the Allies. The decisive battle of the campaign was fought at Leipzig from 16-19 October, when all three main Allied armies converged on the city to attack Napoleon’s positions in and around it. In the largest battle in history up to that time, both sides suffered extremely heavy losses, and though part of the Grande Armée crossed the river Elster and escaped before the bridge was blown, the Allies nevertheless achieved a victory of immense proportions that forced the French out of Germany and back across the Rhine. A Bavarian force under General Wrede tried to stop Napoleon’s retreat at Hanau on 30-31 October, but the French managed to push through to reach home soil a week later. Napoleon, his allies having either deserted his cause or found themselves under Allied occupation, now prepared to oppose the invasion of France by numerically superior armies converging on several fronts.

The Waterloo Campaign (1815)

Napoleon was not content to remain on Elba and manage the affairs of his tiny island kingdom. Landing in France in March 1815 with a small band of followers, he marched on Paris, gathering loyal veterans and adherents from the army as he went, including Ney, whom the king had specifically sent to apprehend the pretender to the throne. Allied leaders were at the time assembled at Vienna, there to redraw the map of Europe, which had been so radically revised by more than two decades of war. The Seventh Coalition was soon on the march, with effectively the whole of Europe in arms and marching to defeat Napoleon before he could raise sufficient troops to hold off the overwhelming numbers which the Allies had now set in motion toward the French frontiers. With the speed characteristic of his earlier days in uniform, Napoleon quickly moved north to confront the only Allied forces within reach: an Anglo- Dutch army under Wellington and a Prussian one under Blücher, both in Belgium. Napoleon could only hope to survive against the massive onslaught that would soon reach France by defeating the Allied armies separately; to this end he sought to keep Wellington and Blücher-who together easily outnumbered him-apart.

On 16 June, after a rapid march that caught Wellington, then at Brussels, entirely off guard, Napoleon detached Ney to seize the crossroads at Quatre Bras, then occupied by part of Wellington’s army, while with the main body of the Armée du Nord he moved to strike Blücher at Ligny. Ney failed in his objective, and though on the same day Napoleon delivered a sharp blow against the Prussians, the crucial result was that the two Allied armies continued to remain within supporting distance of one another. Blücher, having promised to support Wellington if he were attacked by Napoleon’s main body, took up a position at Wavre. Two days later Napoleon did precisely that, focusing his attention on Wellington while the two Allied armies lay apart. Having detached Marshal de Grouchy to follow the Prussians and prevent them from linking up with Wellington, the Emperor launched a frontal assault on Wellington’s strong position around Mont St. Jean, near Waterloo.

The hard-pressed Anglo-Allied troops held on throughout the day, gradually reinforced by elements of Blücher’s army that managed to leave Wavre while Grouchy, busily engaged with a Prussian holding force, re- fused to march to the sound of the guns at Waterloo. The French made strenuous attempts to dislodge Wellington’s troops, who in turn showed exceptional determination to hold their ground, and as the Prussians gradually made their presence felt on the French right flank, the battle began to turn in the Allies’ favor. In a final gamble to break Wellington’s center and clinch victory, Napoleon sent forward the Imperial Guard, but when his veterans recoiled from the intense, point-blank musket and artillery fire they received on the slope, the rest of the army dissolved into a full-scale rout.

With no possibility of retaining power, Napoleon abdicated in Paris a few days later. By the second Treaty of Paris, the Bourbons were restored to the throne, France was reduced to her pre-1792 borders, forced to support an army of occupation and pay a sizable indemnity. As for Napoleon, his hopes of obtaining permission to reside in Britain were dashed; on surrendering himself, he was taken as a captive to spend the remainder of his life on the remote South Atlantic island of St. Helena, where he died on 5 May 1821.