During the battle at Ap Bac near Saigon in January 1963, Viet Cong gunners downed four H-21s and one armed Huey. Regardless of losses, however, by experimentation in actual combat, and applying lessons learned by the French in Algeria, U. S. pilots wrote the book on tactical employment of armed helicopters.

The Viet Cong battalion that fought at Ap Bac in January 1963 was equipped with US M1 Carbines, Browning BAR, .30 cal Browning MG and at least one 60mm mortar. Whilst it is possible that these may have been old ex-French weapons supplied by North Vietnam, I think it more likely that a VC Main Force battalion would be armed with more modern equipment, so probably acquired from US and/or South Vietnamese sources.

Buoyed by its new American weapons and encouraged by its aggressive and confident American advisers, the South Vietnamese army took the offensive against the Viet Cong. At the same time, the Diem government undertook an extensive security campaign called the Strategic Hamlet Program. The object of the program was to concentrate rural populations into more defensible positions where they could be more easily protected and segregated from the Viet Cong. The hamlet project was inspired by a similar program in Malaya, where local farmers had been moved into so- called New Villages during a rebellion by Chinese Malayan communists in 1948-60. In the case of Vietnam, how- ever, it proved virtually impossible to tell which Vietnamese were to be protected and which excluded. Because of popular discontent with the compulsory labour and frequent dislocations involved in establishing the villages, many strategic hamlets soon had as many VC recruits inside their walls as outside.

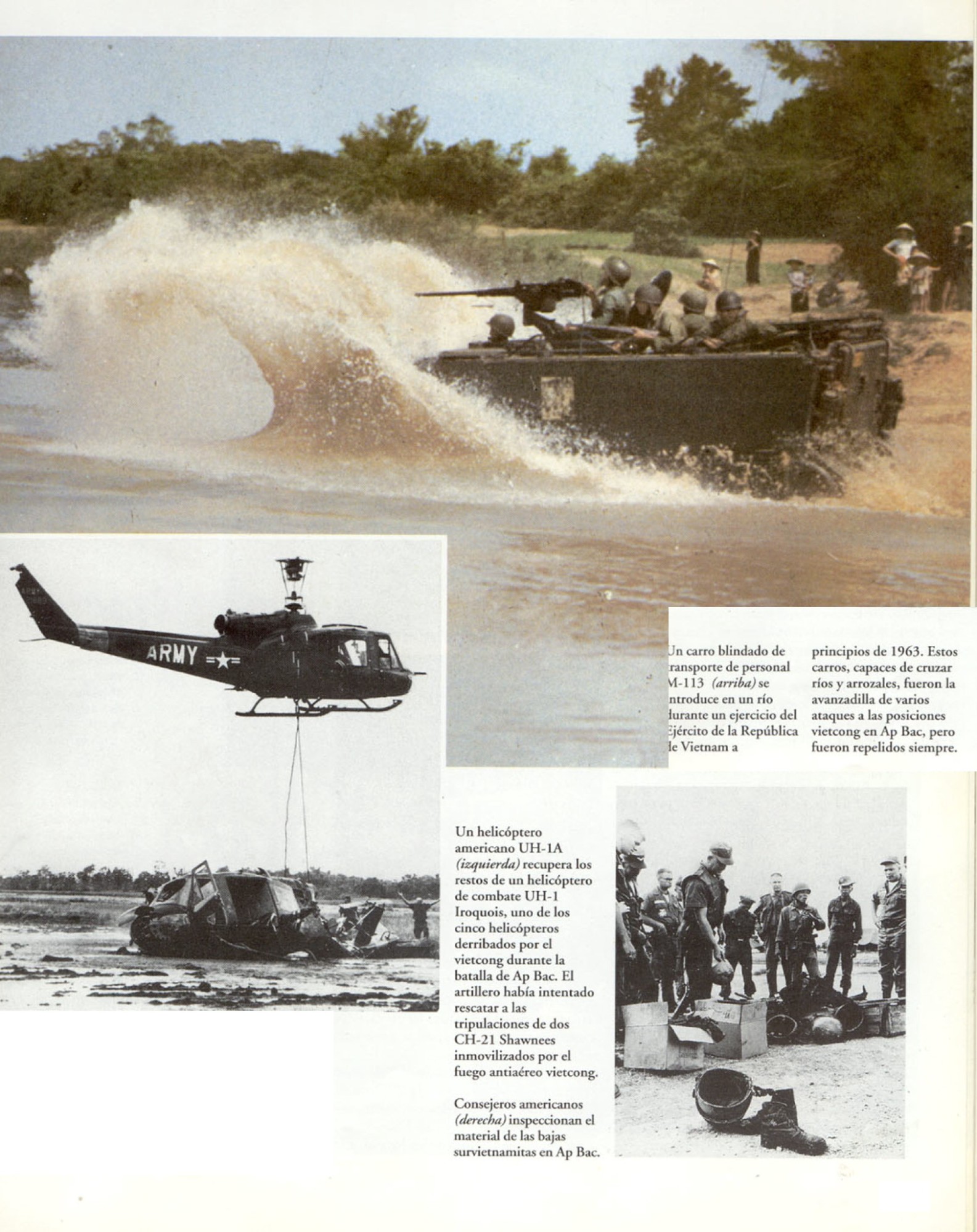

Meanwhile, the Viet Cong had learned to cope with the ARVN’s new array of American weapons. Helicopters proved vulnerable to small-arms fire, while armoured personnel carriers could be stopped or disoriented if their exposed drivers or machine gunners were hit. The communists’ survival of many military encounters was helped by the fact that the leadership of the South Vietnamese army was as incompetent, faction-ridden, and poorly trained as it had been in the 1950s, despite heavier American assistance. In January 1963 a Viet Cong battalion near the village of Ap Bac in the Mekong delta south of Saigon, though surrounded and outnumbered by ARVN forces, successfully fought its way out of its encirclement, destroying five helicopters and killing about 80 South Vietnamese soldiers and three American advisers. By now some aggressive American newsmen were beginning to report on serious deficiencies in the U. S. advisory and support programs in Vietnam, and some advisers at lower levels were beginning to agree with them; but by now there was also a large and powerful bureaucracy in Saigon that had a deep stake in ensuring that U. S. programs appeared successful. U. S. programs appeared successful. The USMACV commander Paul Harkins and U. S. ambassador Frederick Nolting in particular continued to assure Washington that all was going well.

Ap Bac Battle

just before the new year began, a specially-equipped American airplane traced Viet Cong radio signals to the hamlet of Tan Thoi in Dinh Tuong province, the province where the ARVN 7th Division was headquartered. Tan Thoi stood next to the hamlet of Bac, which would later be called Ap Bac after U. S. journalists covering the battle added the prefix ap (hamlet). Jutting abruptly upwards from flat rice paddies, the two hamlets stood out like small islands in a calm green sea. The Americans relayed the location of the Viet Cong radio transmitter to the South Vietnamese high command, which then ordered the 7th Division to take Tan Thoi at the beginning of January. Intelligence reports indicated that the Viet Cong forces guarding the radio transmitter consisted of a reinforced company of 120 men. Thus, the South Vietnamese leadership was aware that the infantry attack was likely to involve significant South Vietnamese casualties.

The Viet Cong actually had a total of between three and four hundred men at Bac and Tan Thoi, most of them belonging to the 261st and 514th Battalions. The 261st Battalion was among the best Viet Cong units in the country, a fact attributable to its fine leadership. Afterwards, American advisers were to say that the Viet Cong soldiers at Bac and Tan Thoi were the most determined Communist fighters they had encountered in more than one year. Equipped with an array of powerful weapons that the North Vietnamese had smuggled to South Vietnam by boat, including machine guns, 60mm mortars, and rifle grenades, the Viet Cong troops were deployed along canals to the north, east, and south of Bac, with the northernmost forces in Tan Thoi. Closely packed fruit trees and dense undergrowth cloaked them well and provided remarkably good protection from heavy weaponry. On thick zigzagged dikes, studded with trees and built up like levees, the Viet Cong dug foxholes so deep that a man could stand inside. Only a direct hit from an artillery shell or bomb could kill the occupant. They dug all of the holes from the rear so that no trace of excavation could be seen from the fighting side. From these foxholes, the Communists could very easily fire down on anything that moved across the surrounding area, so open and flat were the paddies. An American who inspected the Viet Cong positions after the battle remarked that it was akin to firing across a high school football field from the third or fourth row of bleachers. Behind the foxhole line, invisible from the air, ran an irrigation ditch that allowed the Viet Cong to communicate and move men and supplies swiftly along their defensive line, either by sampan or on foot. The Communists’ defensive position at Ap Bac, with its fortified dikes overlooking open rice paddies, bore a striking resemblance to the position from which they had mauled the Ranger company in October 1962.

The Viet Cong, in short, would enjoy tremendous advantages over any foe that tried to attack them. The Communists, indeed, most probably were trying to lure the government forces into attacking by sending out radio signals that understated their strength. In an after-action report, the Communists confided that they had viewed Ap Bac as a much-needed opportunity to demonstrate strength to the peasants and to their own followers, for government victories during the previous year had gravely undermined the prestige of the Communist movement in this part of the delta.

An American adviser, Captain Richard Ziegler, worked with members of the 7th Division’s staff to draft the South Vietnamese battle plan. Certain that the Viet Cong had no more than 120 soldiers guarding the transmitter, the planners created an operational scheme suited for attacking a much weaker enemy than actually existed. According to their plan, an infantry battalion from the 7th Division would fly by helicopter to the north of Tan Thoi and attack southwards. From the south, a Civil Guard regiment under the command of the Dinh Tuong provincial chief would attack northwards. An infantry company riding with a mechanized company of thirteen M-113 armored personnel carriers, also under the provincial chief’s command, would launch an assault from the west. The attack force had a total of twelve hundred troops, with an additional three companies in reserve. No forces would attack from the east. On the basis of the Viet Cong’s past performance, the South Vietnamese officers and their American advisers expected the Viet Cong to flee eastwards when attacked from the other directions. Never had the Viet Cong stood their ground against a large government force outfitted with armored personnel carriers. American aircraft and South Vietnamese artillery would pummel the exposed Viet Cong as they attempted to move east across the rice paddies.

The provincial chief’s units moved forward from the south on January 2 at 6:35 a. m. One hour later, while crossing the flat rice paddies, the Civil Guard came under heavy fire from Viet Cong troops hidden in a tree line. Their forward movement was halted. The Civil Guardsmen attempted to assault the enemy positions twice in the ensuing two hours, but were thrown back each time with high casualties, which included the task force commander, who was shot in the leg, and the lead company’s commander, who was killed. Deprived of its best leaders and facing terrain that heavily favored the enemy, the task force lost all forward momentum. Provincial Chief Lam Quang Tho held the Civil Guard units in place for the rest of the morning and awaited the attack of the 7th Division. The Civil Guard would initiate further offensive action in the afternoon, but without success.

The battalion from the 7th Division that had been scheduled to land by helicopter and assault Tan Thoi from the north was several hours late in attacking, on account of fog that interrupted the helicopter flights. As a result, the guerrillas were able to concentrate troops in the south to fend off the Civil Guard, then concentrate troops to the north to defend against the enemy regulars without fear of simultaneous attacks. The South Vietnamese battalion approached Tan Thoi along three separate axes. Well-concealed Communist troops waited until the government soldiers were twenty yards away, then opened fire. Immediately the attackers were pinned down. In the course of the next five hours, this battalion attempted three assaults against the Viet Cong defenses, all of which failed to break the Viet Cong line.

With the attacks in the north and the south bogged down, the 7th Division’s brand new commander, Colonel Bui Dinh Dam, attempted to stretch out the defenders or find a soft spot by organizing an attack from the east or the west. He asked Colonel John Paul Vann to investigate two possible landing zones for the reserve troops, one to the east of Bac, the other to the west. Flying above the hamlet in an L-19 reconnaissance plane, Vann decided that the western zone offered a better location. Vann said that he did not see any enemy forces near the landing area. One of the 7th Division’s reserve companies clambered aboard a fleet of H-21 helicopters, ungainly old two-rotor machines nicknamed “Flying Bananas” because their eighty-six foot long bodies were shaped like the fruit. The Flying Bananas hauled the infantrymen to a landing site one hundred and eighty meters west of the tree line. Later, in his after-action report, Vann claimed that he had ordered the choppers to drop off the men at a distance of three hundred meters from the tree line – the minimum distance at which .30 caliber small-arms fire was considered ineffective – but the lead pilot had ignored him and taken the helicopters in closer. The responsibility for this fateful decision would become clear later.

During his reconnaissance flight, Vann had failed to see that the Viet Cong had several strong points on the western side of the tree line. The reserve company landed directly in front of these points. As soon as the Flying Bananas touched the ground, they began taking fire. A group of Hueys, escorting the Flying Bananas to provide fire support, closed on the tree line while strafing the guerrillas with their twin .50 caliber machine guns and shooting 2.75-inch rockets in their direction, but their fire failed to suppress the Viet Cong. At one hundred and eighty meters, the Viet Cong could hit the exposed Flying Bananas with considerable accuracy and effect. One of the ten Bananas sustained enough damage that it could not take off after depositing its troops. A second, which had just left the ground, set down again to assist the disabled chopper and was then knocked out of action. A third had to land two kilometers away as the result of hits suffered while unloading troops. One of the Hueys, more heavily armored than the Flying Bananas, came to the aid of the two Bananas that were stuck in the landing zone, but enemy fire ruined the Huey’s tail rotor, causing the helicopter to turn on its side and crash.

The landing zone became a slaughter yard. Droves of South Vietnamese soldiers were shot as they disembarked from the helicopters, their bodies and equipment slumping into the mud. “When those poor Vietnamese came out of the choppers,” one U. S. officer noted afterwards, “it was like shooting ducks for the Viet Cong.” More than half of the company’s 102 men were killed or wounded in the early stages of the fighting. Facing an expertly entrenched opponent and needing to cross one hundred and eighty meters of open and mushy paddy to reach the tree line, the remnants of the company stood no chance of mounting an attack that had any hope of success. One of the first men to appreciate this truth was a helicopter pilot stranded in the paddy, Chief Warrant Officer Carlton Nysewander of Pasadena, California, who had seen combat in Korea as an infantryman. When standing in the paddy, Nysewander noted, a soldier’s feet sank eighteen inches below the surface into dark mud, preventing him from travelling faster than a slow trot. To slosh through open rice paddy at such a pace was to ensure death at the hands of Viet Cong machine gunners. Even a large and able American infantry unit could not have taken the Viet Cong position on its own, Nysewander believed, an assessment that would be validated when American combat units came to Vietnam later on. Defeating the enemy in this setting would require either the utter devastation of the hamlet with large bombs and napalm or the employment of armored vehicles that could shield advancing infantry from the zipping Viet Cong machine gun bullets and pour fire into the Viet Cong defenses. “If you didn’t have something to shield you until you got to the tree line, then you’d be cannon fodder,” observed Nysewander. “Charlie had dug in real well. They had done a wonderful job.”

Vann, who could see the wrecked helicopters from the L-19 and knew that two of the American crewmen were seriously wounded, asked Colonel Dam to send the mechanized company and all other available forces to the landing zone. From a military perspective, Vann’s plan was a poor one, as the landing zone was the most difficult place from which to attack the enemy, but Vann was determined to rescue the American helicopter crewmen, knowing that he bore considerable responsibility for their predicament. It took an hour for Colonel Dam to order the mechanized company to the landing zone, purportedly because of communication difficulties. The company commander, Captain Ly Tong Ba, was slow in moving the company, which was two kilometers west of Bac when he received the order. His reluctance came as a surprise to Captain James Scanlon and Captain Robert Mays, the American advisers assigned to the mechanized company, because Ba was considered one of the most aggressive of the South Vietnamese officers. With Vann screaming over the radio at Scanlon and Mays for Ba to make haste, the two advisers had to badger the South Vietnamese captain to move the company forward. The Americans were not certain what was in Ba’s head. Later, very plausibly, Scanlon speculated, “Perhaps Ba was thinking that because the helos were down and the crews were in danger, the Americans were very excited and emotions were causing them to exaggerate the situation.” It is also possible that one of Ba’s commanders had warned him that the exposed landing zone was a death trap.

While Ba’s carriers were heading east, artillery and air strikes showered down on the Viet Cong positions. To direct the strikes, Vann repeatedly flew a spotter plane over the Viet Cong at a low altitude, a feat of such daring that he was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The artillery and air assets, however, inflicted little damage on the enemy. The Viet Cong’s superlative camouflage made it exceedingly difficult for Vann and others to pinpoint the fighting positions, and the heavy vegetation and the Viet Cong fortifications kept the blasts from wreaking large-scale destruction. “We got a fix on one machine-gun position and made fifteen aerial runs on it,” one U. S. adviser noted. “Every time we thought we had him, and every time that damned gunner came right back up, firing.” Vann also summoned two Flying Bananas and three Hueys to rescue the men marooned in the rice paddies, but one of the Flying Bananas was brought down by enemy fire, becoming the fifth and final helicopter casualty of the battle. Vann then aborted the helicopter rescue operation.