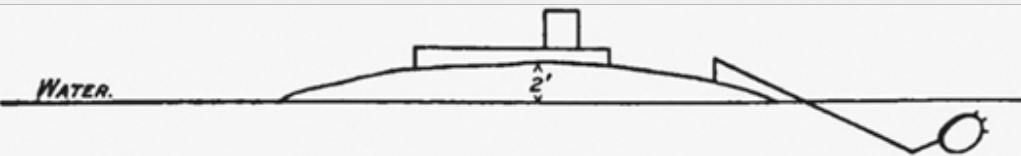

First sketch of CSS David, according to Rear Admiral

Dahlgren

Like many good stories, this one begins with a bang and a

considerable amount of drama. When in the evening hours of 5 October 1863

darkness was descending on the port of Charleston, a small, cigar-shaped craft

was silently slipping off its moorings. Lieutenant William T. Glassell,

Confederate States Navy, had assumed command of the CSS David, as the unusual

vessel was named, barely a fortnight before. The David made for the ships of

the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which kept Charleston closed for all

but the most enterprising blockade runners. Glassell’s orders were clear: “You

… will proceed to operate against the enemy’s fleet … with a view of destroying

as many of the enemy’s vessels as possible” (Tucker 1863). His craft was armed

with a single spar-torpedo.

Glassell went straight for what in the eyes of the

Confederates defending Charleston must have been the main prize: the USS New

Ironsides, the Union navy’s biggest ironclad, a 230-foot vessel displacing over

4,100 tons that, due to its combination of heavy armor and heavy firepower, was

probably the most powerful warship the Union could muster. Stationed off

Charleston since February 1863, the ship had not only seen considerable action

during the First Battle of Charleston Harbor and the fighting around Fort

Wagner (Roberts 1999:44–75), but also it already had been the target for an

attack on the night of 20 August 1863. The torpedo vessel CSS Torch, commanded

by Capt. James Carlin, a blockade runner, had unsuccessfully tried to hit the

Union ironclad with three torpedoes, each carrying 100 pounds of gunpowder

(Campbell 2000:42–52). While Carlin managed to get fairly close to his target,

his attempt was frustrated mainly by the utter unreliability of his vessel’s

engines, prompting him to report afterwards:

It was my intention to attack one of the monitors [after

the failed attack on USS New Ironsides], but after the experience with the

engine, I concluded it would be almost madness to attempt it.… I feel it my

duty most unhesitatingly to express my condemnation of the vessel and engine

for the purposes it was intended. (Carlin 1863:499)

Six weeks later, Glassell was trying to succeed where Carlin

had failed. At about 9:15 PM, the David was noticed for the first time from the

deck of New Ironsides, yet it was already too late; Glassell (1877:231) later

estimated having been about 300 yards from his target. Before the Union

ironclad could react, it was rammed on its starboard side, the torpedo going

off just a minute after the Confederate vessel had been hailed (Rowan 1863:12).

The explosion left New Ironsides rattled but still afloat and outwardly

intact—closer inspection would later reveal considerable damage, though not

enough to put her out of action (Bishop 1863). Even today there is still some

discussion on the extent of the damage (Roberts 1999:82–83; Campbell

2000:65–66), yet the basic fact that she did not immediately leave station

shows clearly that the attack had failed in its main purpose. For a few moments

after the explosion, small-arms fire was directed at the Confederate torpedo

boat as it slid past the Union ironclad, and eventually two armed cutters were

sent out, though they failed to locate it (Rowan 1863:13; Glassell 1877;

Roberts 1999:80–83; Campbell 2000:59–66). The David had managed to slip off

into darkness again, or so it seemed.

All was not well, however, aboard the Confederate torpedo

boat. The column of water thrown up by the explosion had forced water into the

ship and extinguished the fires of her engine, which was furthermore jammed by

iron ballast cast loose and thrown around by the shock of the explosion. The

David had not cunningly made off into the cover of darkness again; she had

simply, and rather helplessly, drifted away. With his vessel hors-de-combat and

apparently sinking, Glassell ordered his small crew of three—pilot, engineer,

and fireman—to abandon ship (Tomb 1863:21). But this was not quite the end of

that night’s drama: Glassell and the fireman were captured, and it was from

questioning them that Admiral Dahlgren, who at the time was commanding the

South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, got firsthand information about the nature

of the vessel that had attacked New Ironsides (Dahlgren 1863b; Campbell

2000:59–65), including a rough sketch of its general layout. The pilot of the

David, however, eventually got back aboard, picked up the engineer from the

waters of the harbor, managed to restart the engine, and finally brought the

David back to Charleston, from where she would venture out again in March 1864

in an unsuccessful attempt to attack the USS Memphis (Lee 1864; Patterson 1864;

Tomb 1864; Campbell 2000:79–82).

Lieutenant Glassell’s exploits—and even more his unusual

vessel—captured the imagination of his contemporaries. In fact, after the USS

Monitor and CSS Virginia, the CSS David may well be the most iconic warship of

the American Civil War, with her dramatic attack on New Ironsides being one of

the better-known naval engagements of the conflict. Given the novelty of

torpedo warfare in general and her unusual construction in particular, it is

far from surprising that interest in the David—and other Confederate torpedo

vessels, particularly submarines—has mainly concentrated on the inventors,

engineers, and men commanding these craft; their technical ingenuity; and the

obstacles they faced by putting their contraptions, none of which would have

passed any health-and-safety tests today, into operation.

Yet the history of the Confederate torpedo boat effort is

not only a history of valiant men sailing into harm’s way on a mixture of

crackpot engineering and sheer bloody-mindedness; it also forms part of the

overall history of the torpedo, or of the spar-torpedo, to be more precise. And

whereas the later history of the torpedo already does not exactly suffer from

an excess of academic interest—Edwyn Gray (2004:vii) called the torpedo “one of

the world’s most underre-searched weapons”—the spar-torpedo has fared even

worse; no modern history of the weapon itself, its employment, and its carriers

is available, and general studies on the history of the torpedo either leave it

out completely (Gray 2004) or devote but a few pages to it (Branfill-Cook

2014:18–20). Indeed, for an overview of the actual use of the spar-torpedo, a

study published in 1880 by Charles William Sleeman (1880:187–203), who had

served in the Royal Navy from 1869 to 1877 and joined the Ottoman navy afterwards,

still remains the primary reference.

This chapter examines the employment of spar-torpedo boats

in the American Civil War from an operational perspective and puts it into the

overall context of the history of the spar-torpedo, a history that arguably

begins in the United States a good half century before the war and ends before

the turn of the century.

SPAR-TORPEDOES AND SPAR-TORPEDO BOATS

The CSS David’s October 1863 attack on the USS New Ironsides

offers an excellent illustration of the key issues with operating spar-torpedo

boats. These issues are perhaps best, if somewhat dryly, summarized by George

Elliott Armstrong (1896:72), formerly Royal Navy: “In fact, the guiding

principle of the spar torpedo is that its construction and design render it

necessary that wherever the torpedo goes the operator must go too.” It might be

added that Armstrong, writing in 1896, clearly did not think the spar-torpedo to

be a viable weapon anymore, as he continued:

Nowadays it would be almost impossible for a steamboat to …

coolly point the nose of a torpedo against her [an enemy ship’s] water-line;

for … she [the torpedo boat] would, unless the whole enemy’s crew were asleep,

be received with an overwhelming storm of lead and steel from the quick-firing

and machine guns.

The reason for the torpedo vessel’s need to get into

physical contact with its target lies with the nature of the spar-torpedo

itself. In principle, it was a very simple instrument: it usually comprised a

long spar, 35 feet in length or more, and at its end an explosive-filled

canister armed with some sort of fuse. Three factors were important for its

operational success. First of all, the combination of fuse and main charge had

to work—this was not the case during the David’s March 1864 attack on the USS

Memphis, which was rammed twice without success, apparently causing

considerable frustration among the Confederate operators (Tomb 1864; Campbell

2000:79–80). Second, the charge had to be both sufficiently powerful and—for

maximum effect—placed in the right position at some point below the waterline;

the lack of success during the David’s attack against New Ironsides was, on the

following day, ascribed by General Beauregard (1863) either to an insufficient

powder charge or to the torpedo having been placed too close to the surface.

Finally, of course, with the spar-torpedo essentially being a zero-range

weapon, the torpedo had to get to the target in the first place, which meant

driving the spar-torpedo boat headlong into the target ship.

Whereas operating a spar-torpedo boat appears, in

retrospect, to be near suicidal, one must realize that until the invention of

the quick-firing gun in the 1880s and its employment on ships precisely against

torpedo boats, the heavy guns of a warship usually had such a long reload time

that it was, at least in theory, possible to get close to the enemy before

being shot to pieces. In fact, the closer one got, the safer one actually was,

as heavy guns on a warship allowed only a small degree of depression, thereby

creating a “dead zone” around the ship that could not be covered by them. So

having dodged the few large-caliber projectiles his enemy could hurl at him,

the enterprising commander of a spar-torpedo boat would, once inside this dead

zone, have to face small-arms fire only, though that of course still posed a

considerable risk if his craft were detected early, as a large and alert crew

was likely to open up at the torpedo boat with everything available on the

ship.

Given the characteristics described above, the spar-torpedo

could find employment in three different ways, all of which are in evidence in

the American Civil War. First of all, a spar-torpedo could be attached to a

full-fledged warship as a secondary weapon of opportunity—or as a weapon of

last resort, for that matter—to increase the impact of a ramming maneuver.

Perhaps the best-known example from the American Civil War is the Confederate

ironclad CSS Atlanta mounting a spar-torpedo with a charge of 50 pounds of

gunpowder (Barnes 1869:122–23; Emerson 1995:375); after her capture by Union

forces on 17 June 1863, she was commissioned into the Union navy and continued

to carry her spar-torpedo, though it was never actually used in action.

Spar-torpedoes could furthermore be employed on an ad-hoc

basis to allow for fitting out powered boats as the opportunity for their

employment arose; perhaps the most famous example from the American Civil War

is the sinking of the CSS Albemarle in October 1864 by a spar-torpedo-armed

steam launch under the command of Lt. William B. Cushing, U.S. Navy (1864; see

also Cushing 1888). Cushing’s craft was essentially a converted picket boat

with the spar-torpedo mounted on the side of the vessel (drawings in Macomb

1864:622–623). After the Civil War and well into the last decades of the

century, the spar-torpedo continued to be carried aboard U.S. warships, with

the last official set of instructions published by the U.S. Torpedo Station

dating from 1890 (Navy Torpedo Station 1890); an earlier version (Navy Torpedo

Station 1876) also included a chapter on towing torpedoes, a concept that by

the 1880s had fallen out of use. Even as late as 1890, the instructions not

only made a distinction between torpedoes carried by ships and those carried by

boats but also described how “torpedoes may be readily improvised from kegs or

casks” (Navy Torpedo Station 1890:24–25).

Finally, in a small vessel the spar-torpedo could constitute

the sole or primary armament, resulting in a “true” spar-torpedo boat. During

the American Civil War such vessels were used nearly exclusively by the

Confederate navy; while general circumstances prevented the building of classes

of torpedo boats proper, at least three more-or-less distinct “types” of

torpedo boats can be made out. The CSS David was built to maximize protection

for its small crew and to minimize its silhouette, allowing it to approach an

enemy unseen. Its design included both iron covers for the small crew of four

as well as ballast tanks for lowering it as far as possible into the water,

though it is not quite clear whether the original David already had the latter

feature (Campbell 2000:56).

Given the David’s apparent success, it is hardly surprising

that she served as a model for a number of other torpedo boats built during the

war. Two of these are shown in a set of pictures taken after the war in

Charleston harbor, where Admiral Dahlgren reported three operational boats sunk

by their Confederate crews in Charleston harbor after the fall of the city and

six others in various state of (dis)repair (Dahlgren 1865:387, 402). Apart from

the Charleston-based torpedo boats, at least one David-type boat was active in

Mobile. It had originally been built on a government contract in Selma,

Alabama, by a man called John P. Halligan, whose conduct apparently failed to

impress Maj. Gen. Dabney H. Maury (1865:267), who reported in January 1865 that

from his whole course I became convinced he had no real

intention of attacking the enemy and that the only practical purpose the Saint

Patrick was serving was to keep Halligan and her crew of six able-bodied men

from doing military duty.

Eventually, Maury effectively confiscated the boat that

apparently had been lying at Mobile since June 1864 (Johnston 1864:936), its

existence known to Union forces since late October (La Croix 1864; Welles

1864). The Saint Patrick, under the command of a Confederate navy officer,

attacked the double-ended gunboat USS Octorara during the night of 27 January

1865, though without success as the torpedo failed to explode (Maury 1864; see

also Hurlbut 1864; Jones 1864; Campbell 2000:84–86). Another David-type boat

operating out of Mobile was mentioned as being destroyed in May 1864 by a boiler

explosion during an attack on blockading vessels off Sand Island (von Scheliha

1868:314). While further details about this craft are unknown, it clearly

cannot have been the Saint Patrick. The existence of this second David-type

torpedo boat may lie at the roots of conflicting reports on whether Saint

Patrick really was a David-type boat or whether it might actually have been a

submersible.

While the “Davids” form the first type of Confederate

torpedo boat construction, various Confederate experiments with submarines can

conveniently be grouped together as the second type (Ragan 1999). Although

these are outside the scope of this chapter, it should be noted that during and

after the war considerable confusion existed as to whether certain Confederate

torpedo craft were in fact submarines or not. To take just one example, when

Admiral David D. Porter (1878:231) observed that the Davids “drowned their own

people oftener than those they were in pursuit of,” he was clearly thinking of

submarines like the CSS Hunley and not of “true” David-type torpedo boats.

This leaves vessels of yet another design as the third type.

These were essentially copies of the CSS Squib, a small, open steam launch that

offered only a minimum of protection but apparently was quite fast and

maneuverable (Barnes 1864; Campbell 2000:92–94). The Squib, together with the

David, is probably the best-known Confederate torpedo vessel and for some

reason is the only Confederate torpedo boat to appear in the collection of

statistical data on “Confederate States Vessels” published by the Naval War

Records Office (Anonymous 1921:267). It was led by Cmdr. Hunter Davidson,

Confederate States Navy, in an attack against the USS Minnesota (Gansevoort et

al. 1864) without, however, actually sinking the ship (Anon. 1864; Campbell

2000:95–99). The Confederates built several similar boats, of which the CSS

Scorpion, CSS Wasp, and CSS Hornet of the James River Squadron are the least

obscure (Campbell 2000:105). They took part in the Battle of Trent’s Reach in

January 1865, one of the last large naval engagements in the war and the only

one where, at least on paper, both sides operated spar-torpedo boats (Anon.

1865; Campbell 2000:105–115), though neither side actually used them in the

intended role. While in theory Squib-type boats, which were basically only

steam launches, should have been easier to build than David-type boats, they

suffered from the same problem the Davids did—the lack of suitable high-quality

engines for speed and maneuverability.

This difficulty of providing suitable engines not only

turned out to be the perennial bane of Confederate torpedo-boat building, it

also points at an important characteristic of the spar-torpedo boat: while the

method of bringing the spar-torpedo into contact with the opponent—that is,

ramming—could appear to be archaic in the true sense of the word, in a naval

conflict of the 1860s it meant the carrier vessel required an engine that was

small, reliable, and capable of turning out considerable power. That was a technological

requirement evidently beyond the capabilities of Confederate industry. It is

well worth dwelling for a moment on the engine problems plaguing the

Confederate torpedo boat effort. Obviously, when it came to torpedo boat

design, Confederate engineers displayed as much ingenuity as anyone else, or

more, yet turning ingenuous designs into working warships proved to be the real

problem. Spar-torpedo boats were technically demanding machines; their

specifications—small to the point of being stealthy, powerful engine, and high

maneuverability—tested Confederate technical capabilities to the limit.

SPAR-TORPEDO BOAT OPERATIONS IN THE CIVIL WAR: NOT EXACTLY A

SUCCESS STORY

Given the limitations of the technology available and the

difficulties the Confederate navy had in procuring suitable material, it is

hardly surprising that on the whole spar-torpedo boats were unsuccessful during

the war. Ships like the CSS David, CSS Hunley, or the launch used by Lt.

Cushing certainly captured the imagination of contemporaries and could in some

case even enjoy limited success, yet their impact on the course of the war was

negligible, particularly because the actual number of successful attacks was

minimal. Whereas a list of ships damaged or sunk by Confederate “torpedoes”

(Perry 1965:199–201; Schiller 2011:139–167) appears impressive at first, closer

inspection reveals that nearly all ships were sunk or damaged by mines. While

the Union navy lost four monitors and four other armored vessels to mines, the

only ironclad sunk by a spar-torpedo boat attack during the American Civil War

was the CSS Albemarle. Also, of six unarmored gunboats, only one, the USS

Housatonic, fell victim to a spar-torpedo attack by the Confederate submarine

Hunley.

On the whole, mines proved to be a much more serious

obstacle, particularly during the river campaigns. Not only were they

materially effective in causing the loss of a considerable number of warships

and transports, they also made various countermeasures necessary, significantly

slowing progress on the rivers. Additionally, mines came in a large variety of

types, some of which could be produced in the field (Bell 2003:477–492).

Minefields could be prepared at fairly short notice, and the mere possibility

of encountering them already had a significant impact on operations. Simply

put, for a modicum of effort, mines offered great returns (Steward 1866:23–25).

This was clearly not the case with spar-torpedo boats. It

has already been noted that the operation of spar-torpedo boats posed

considerable technical challenges. Moreover, even if one actually saw action,

its value was limited. Had the CSS David sunk the USS New Ironsides on that

October day of 1863, the strategic significance of its success would probably

have been minimal. Success by the David certainly would have given the

defenders of Charleston a considerable moral boost—its importance is amply

illustrated by the reward set up for its sinking, which was set at $100,000

(Roberts 1999:74)—yet the defense of the port rested primarily on a formidable

combination of coastal batteries, mines, and ironclad warships, making any

Union foray into the harbor a potentially very dangerous undertaking. In this

context, the spar-torpedo boats were both an additional deterrent against any

attempt of forcing the harbor and a weapon of opportunity with which to attack

individual vessels of the blockade squadron if circumstances were favorable.

Even taking individual successes into account the spar-torpedo boats were never

a serious threat to the blockade itself; they were far too few in number, and

the Confederate navy lacked not only the technical resources for operating them

in a strategically meaningful way but also anything resembling an operational

doctrine. In the few cases when spar-torpedo boats actually pressed attacks

home, they did it on their own; apparently no serious attempts were made at

coordinating the available torpedo craft.

The general idea of coordinating attacks by small boats

armed with torpedoes, however, was not exactly a new one. In 1810, more than

half a century before Lt. Glassell led the CSS David against the USS New

Ironsides, Robert Fulton published Torpedo War and Submarine Explosions to

present his ideas both on the design of a torpedo craft and how it was to be

used. Fulton had in preceding years tried to convince authorities in England

and France of his theories on torpedo warfare. In October 1805, he even managed

to blow up a ship with a container of explosives positioned below the keel of

the vessel; what Fulton termed a torpedo might better be described as a

drifting mine, but it should have served to silence the sceptics. As Fulton

(1810:8) dryly noted: “Capt. Kingston asserted, that if a Torpedo were placed

under his cabin while he was dinner, he should feel no concern for the

consequence. Occular [sic] demonstration is the best proof for all men.” Fulton

(1810:10–13) also proposed the employment of anchored torpedoes (or moored

mines).

Yet another idea was to actively bring the torpedo into

contact with an enemy ship. The explosives container would be attached to a

line that, in turn, was attached to a harpoon; the harpoon would be lodged in

the hull of an enemy ship under way, and the container at the end of the line

would be sucked under the hull to explode. In the case of an enemy vessel at

anchor, Fulton hoped the current would do the trick (Fulton 1810:13–20).

Although the idea might seem more than only a little bit impractical, Fulton

(1810:15) claimed to have “harpooned a target of six feet square fifteen or

twenty times, at the distance of from thirty to fifty feet, never missing.”

Setting aside the questionable reliance on currents—and the

slightly irritating picture of Fulton banging away at a target with a

blunderbuss-turned-harpoon-gun—the overall operational concept is nevertheless

quite noteworthy. For one, he actually devised an operational concept for the

individual weapon system he designed. Fulton (1810:21–23) envisaged large

numbers of his small boats swarming around the larger warships of a blockading

force, preferably at night, and homing on their target from different

directions so as to prevent the warships from concentrating their fire. He even

went so far as to calculate the relative costs of an 80-gun vessel of 600 men

and of 50 “torpedo boats” of 12 men each. While the warship, according to his

calculation, was a massive investment at $400,000, the flotilla of boats armed

according to his plans would come in at a mere $24,300, based on the assumption

that it was possible to get a harpoon gun for $30 and a blunderbuss for $20

(Fulton 1810:21). Fulton seems to have clearly grasped what have been basic

principles of torpedo (and later missile) boat operations ever since:

comparatively low cost allowed torpedo boats to attain numerical superiority,

making it possible for them to attack from different directions, thereby

significantly degrading the defensive capabilities of the intended target. And

like many later proponents of torpedo-boat construction, Fulton seemed to have

cared little for the inherent weaknesses of his torpedo craft, which were

liable to suffer considerably from any but the best sea and weather conditions.