Principalities of the later Kievan Rus (after the death of Yaroslav I in 1054). (the background map is a modern map of Europe showing current national boundaries, and modern artificial waterways and reservoirs in Russia)

Grand Prince Vladimir approached the matter methodically. He

sent envoys to inquire into Islam, Judaism, and Eastern and Roman Christianity.

He studied their reports and listened to preachers expounding the virtues of

each faith. According to the Primary Chronicle, however, he was impressed most

of all by the fervent description of Orthodox worship given by his envoys on their

return from Constantinople. They had attended divine service in the Cathedral

of St. Sofia and had been so transported by its magnificence that, so they

said, “We knew not whether we were in heaven or on Earth.” A further reason for

embracing Orthodox Christianity, advanced by Vladimir’s advisers, was: “If the

Greek faith were evil, it would not have been adopted by your grandmother Olga

who was wiser than all men.”

The cultural, commercial, and military prestige of Byzantium

stood so high among the Russians that it was perhaps inevitable that they

should have taken their religion from Constantinople. To them, the imperial

city was the bastion of civilization. Immediate political considerations also

played an important part. At this time, the young Byzantine Emperor Basil II

was eager for friendly relations with the Kievan grand prince. He urgently

needed Russian support to defend Constantinople against a provincial uprising

in Anatolia. Early in 988, Basil’s envoys reached Kiev, bringing the offer of marriage

with his sister, Princess Anna, in return for a detachment of Varangian troops

in Kiev’s service. His proposal, of course, involved Vladimir’s conversion.

Members of the imperial family were called Porphyrogenetes,

or “born in the purple.” They did not marry foreigners, and proposals of

marriage from European royal families were loftily rejected. Vladimir was

keenly aware of the honor and the great prestige that he would gain for himself

and the Rurikide dynasty by this marriage. He accepted without delay and was

baptized in Kiev in February 988. Moreover, he promptly fulfilled his part of

the bargain by sending a force of 6,000 Varangians, who were to play a leading

part in the defeat of Byzantium’s enemies. (Some years earlier, Vladimir, in a

less generous mood, had reportedly sent a retinue to Greece in an effort to

cleanse Kiev of the most unruly of these adventurers. He had recommended to the

Greek emperor: “Do not keep many of them in your city, or else they will cause

you such harm as they have done here. Scatter them, therefore, in various

localities, and do not let a single one return this way.”)

Basil appeared reluctant, however, to send his sister to

Kiev. Negotiations regarding the degree of autonomy to be accorded the Russian

Church further complicated matters; Vladimir was not prepared to accept the

political control that could follow upon conversion. Finally, in 989, angered

by the slowness of the Greeks to honor the marriage arrangement, Vladimir

launched a campaign against the Crimea, then part of the Byzantine Empire. He

intended to pressure the emperor and also to gain control over the episcopal

sees in the peninsula. In July, his troops captured the important town of

Kherson, apparently convincing the emperor he could no longer evade the

marriage. Princess Anna was dispatched to Kherson, where she was at once

married to Vladimir, and he then returned the captured town to the emperor as

“the bridegroom’s gift.” In the spring of 990, Vladimir arrived with his bride

in Kiev, bringing with him several priests from the Crimea, as well as icons,

sacred vessels, and relics of saints captured during his peninsular campaign.

Vladimir next sent instructions to Novgorod and other towns

that all people must be baptized without delay. He ordered the destruction of

pagan temples and idols, and forbade the heathen priests and magicians to

practice their arcane ceremonies. In Kiev, the statue of Perun, the god of

thunder and lightning who had been the chief deity, was tied to the tail of a

horse and dragged ignominiously into the Dnieper. Other idols, raised in

worship of the forces of nature, suffered a similar fate. The people were

bewildered; their familiar gods were being destroyed, but they understood

nothing of the new faith that they were ordered to embrace. In many places,

they rebelled against the destruction of their idols, but their rebellions were

put down. Christian churches were hastily built. In 990, the erection of Kiev’s

Cathedral of the Dormition of the Holy Virgin was begun in stone, and six years

later, it was completed. Such churches, giving solid physical form to the new

religion, made acceptance easier, although the old pagan rites persisted.

Vladimir took his new faith very seriously. Practical

considerations aside, his conversion was evidently sincere, as his works

demonstrated. The chronicler recorded:

He invited each beggar and poor man to come to the

Prince’s palace, and receive whatever he needed, both food and drink, and money

from the treasury. With the thought that the weak and the sick could not easily

reach his palace, he arranged that wagons should be brought in, and after having

them loaded with bread, meat, fish, various vegetables, mead in casks, and

kvas, he ordered them driven out through the city. The drivers were under

instruction to call out, ‘Where is there a poor man or a beggar who cannot

walk?’ To such they distributed according to their necessities.

Vladimir had been noted for his love of war, his

ruthlessness, and his pleasure in women. Before his conversion, he was said to

have had 800 concubines living in three large harems, and also seven wives. The

monks who compiled the Primary Chronicle were undoubtedly eager to portray him

as a sinful man who changed his ways completely after conversion. To promote

veneration of their first Christian ruler, they may well have exaggerated the

transformation. Vladimir nevertheless appeared to undergo a complete change of

heart: The warlike, sensual heathen was in his later years judged a saintly

ruler; in the thirteenth century, he was canonized.

The conversion of the Russian people to the Christianity of

the Eastern Church was one of the most significant events in Russian history.

Although imposed upon the people, who clung for many years to their heathen

creeds, the Orthodox faith was to sink deep roots in Russian society. It

gradually permeated their lives and helped to shape their history, their

culture, and their national character. The immediate result was to bring closer

relations with Christian Europe. The dynasty of Rurik would be linked by the

end of the eleventh century with the ruling families of France, England, Hungary,

Poland, Bohemia, and the Scandinavian countries. Kievan Rus belonged to the

European comity of nations, and no one questioned its membership. But in later

centuries, the fact that the Russians had embraced Eastern Christianity was to

be one of the factors alienating them from the Roman Catholic West. It would

contribute to their isolation from the mainstream of Western development and to

the division of Europe into east and west.

The death of Vladimir in 1015 was followed by more savage

fratricidal struggles for power. He had evidently intended that Boris, his son

by his Byzantine wife Anna, succeed him as grand prince. Boris was returning

from a campaign against the rebellious Pechenegs when he learned of his

father’s death and also of the seizure of Kiev by Svyatopolk, his half-brother.

As an earnest Christian, however, he refused to fight against his own brother.

He sent away his army and retinue, and quietly awaited assassins sent by

Svyatopolk, who killed him and also his brother, Gleb.

Yaroslav of Novgorod alone among Vladimir’s sons was ready

to stand against the treacherous Svyatopolk. He had the full support of the

Novgorodtsi, who had long resented the primacy of Kiev. Indeed, the war between

the two brothers, lasting four years (1015 to 1019), was a struggle between the

two cities. Yaroslav finally defeated Svyatopolk, but then found himself

challenged by yet another brother, Mstislav. Their struggle ended in an

agreement to divide the country into two parts; Yaroslav took the lands west of

the Dnieper, and although Kiev was in his territory, he continued to reside in

Novgorod; Mstislav, ruling over the lands east of the Dnieper, made Chernigov,

130 miles northeast of Kiev, his capital. In 1036, while on a hunting

expedition, Mstislav died. As he left no heir, Yaroslav became grand prince,

moving to Kiev – whence he ruled over the whole of Russia, save the small

eastern enclave of Polotsk.

The reign of Yaroslav the Wise (called the Lawgiver), from

1036 to 1054, carried Kiev to the zenith of its power and prestige. He

established that the patriarchate of Constantinople would ordain the

metropolitan of Kiev as the head of the Russian Church, thus making Kiev the

ecclesiastical as well as the political capital of Russia. Byzantine influence

remained strong, and taking Constantinople as the paragon, he was active in

developing Kiev as an imperial city. He engaged Greek masters to build a

cathedral, dedicated to Saint Sofia, and also a new citadel, known as the

Golden Gate. He was tireless in erecting new buildings. By the end of his

reign, Kiev had become a beautiful city, and in size and wealth, one of the

greatest in Europe. It had advanced as a center of civilization and trade far

beyond most of the cities in the West. Foreign visitors reported that it

rivaled Constantinople.

Kiev also developed as a center of learning. This was

closely connected with the founding of new monasteries, including the Monastery

of the Caves, which became renowned for the sanctity and the learning of its

monks. But Yaroslav himself contributed directly to this interest in learning.

He “applied himself to books and read them continually day and night. He

assembled many scribes to translate from the Greek into Slavic. He caused many

books to be written and collected. . . . Thus Yaroslav . . . was a lover of

books and, as he had many written, he deposited them in the Church of St.

Sofia.” Historians have disputed his authorship of even part of the Pravda

Russkaya (“Russian truth”), the code of laws, but the legend reflects the

spirit of learning and justice that evidently marked his reign.

It is certain that this first Russian code of laws was

compiled under his sponsorship and that its rules derived in part from the

tribal common law of the day, and in part from Byzantine law – itself evolved

out of Roman law. Only two peace treaties concluded between the Russians and

the Byzantines in the tenth century predate the Pravda Russkaya as written

Russian law.

Yaroslav’s eighteen decrees tell much about the nature of

life in the Kievan Rus of his day; blood revenge was customary, though the

grand prince reserved the right to limit those permitted to take it. Article

One of Yaroslav’s Pravda declares: “If a man kills a man [the following

relatives of the murdered man may avenge him]: the brother is to avenge his

brother; the son, his father; or the father, his son; and the son of the

brother [of the murdered man] or the son of his sister, [their respective

uncle]. If there is no avenger, [the murderer pays] 40 grivna. . . .” Lesser

offenses were generally dealt with by fining the guilty. A number of articles

deal with payment for physical injury: “If anyone hits another with a club, or

a rod, or a fist, or a bowl, or a [drinking] horn, or the butt [of a tool or of

a vessel], and [the offender] evades being hit . . . he has to pay 12 grivna. .

. . If a finger is cut off, 3 grivna. . . . And for the mustache, 12 grivna:

and for the beard, 12 grivna.” Eight articles deal with crimes against

property. “If a slave runs away . . . and [the man who conceals that slave]

does not declare him for three days, and [the owner] discovers him on the third

day, he . . . receives his slave back and 3 grivna for the offense. . . . If

anyone rides another’s horse without asking the owner’s permission, he has to

pay 3 grivna.” From these simple, sometimes harsh, beginnings would evolve

Russia’s legal code. Evidence that the state was growing quickly is suggested

by the fact that Yaroslav’s sons would soon find it necessary to greatly

enlarge its jurisdictions.

Sensing the approach of his own death, Yaroslav called his

five sons together to proclaim his will, saying, according to the Primary

Chronicle:

My sons, I am about to quit this world. Love one another,

since ye are brothers by one father and mother. If ye abide in amity with one

another, God will dwell among you, and will subject your enemies to you, and ye

will live at peace. But if ye dwell in envy and dissension, quarreling with one

another, then ye will perish. . . . The throne of Kiev I bequeath to my eldest

son, your brother Izyaslav. Heed him as ye have heeded me, that he may take my

place among you. To Svyatoslav I give Chernigov, to Vsevolod Pereyaslav, to

Igor the city of Vladimir, and to Vyacheslav Smolensk.

However fanciful, this account is used by most historians to

explain the ranking of city-states that were affected at this time. Kiev was to

continue as the great principality; with the death of its prince, lesser

princes would move up one step, the prince of Chernigov occupying Kiev and so

on. The system was generally observed in the breach. Bitter dissensions soon

broke out. The three elder sons formed a triumvirate, but they were unable to

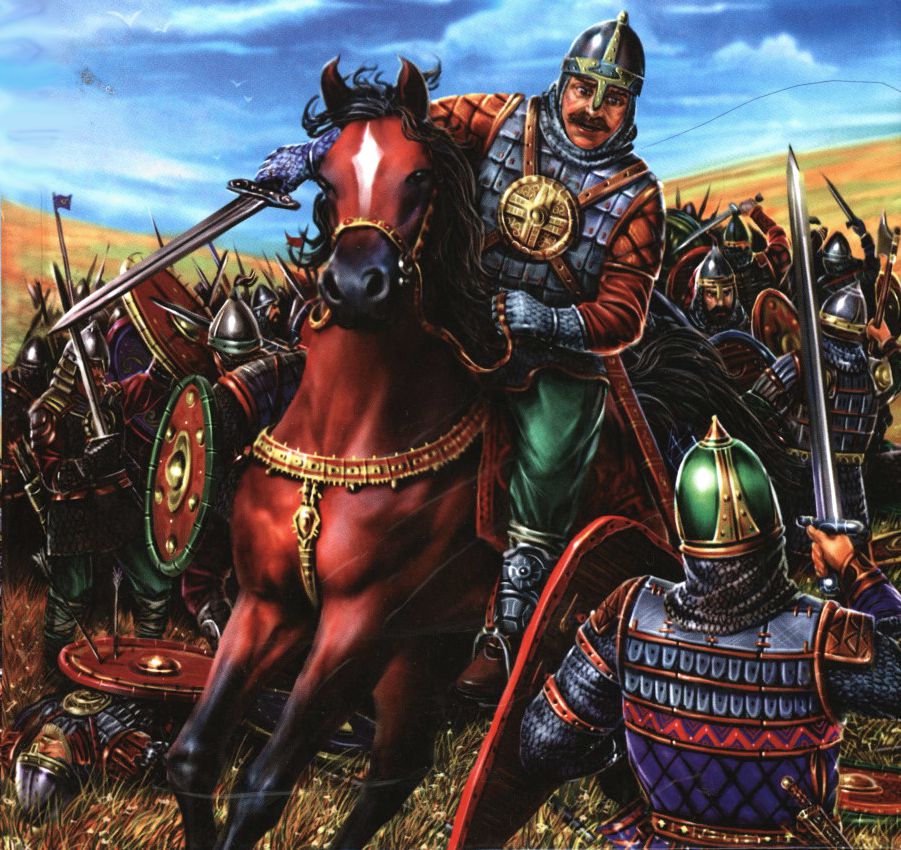

impose order. Meanwhile, the Pechenegs had ceased to be a danger. The Turkic

Cumans had taken their place and were now harassing the Russians, shutting off

their trade routes to the south. Their rise marked the beginning of a time of

hardships for Kievan Rus. Of the year 1093, the chronicler reported: “Our own

native land has fallen prey to torment; some of our compatriots are led into

servitude, others are slain, and some are even delivered up to vengeance and

endure a bitter death. Some tremble as they cast their eyes upon the slain, and

others perish of hunger and thirst.” They sacked Kiev, leading away slaves who

“made their painful way naked and barefoot, upon feet torn with thorns, toward

an unknown land and barbarous races.”

Rivalries over the succession caused discontent to grow. The

period of stability and good government the Russians had known under the wise

rule of Yaroslav made them all the more impatient of the conflicts between his

sons. The Grand Prince Izyaslav fled to Poland following the second conflict

with his brothers, leaving Kiev to Svyatoslav, but not before the city had

twice been victim to fratricidal strife. The princely system, as it had

developed in Kievan Rus, provided that the first duty of the grand prince was

to maintain order and defend the country. But the struggles for power were now

promoting internal disorder and weakening the defenses of the country against

their Asiatic enemies. In an attempt to regulate the succession and to avoid

further rivalries, the numerous princes of the Rurikide dynasty met together at

Lyubech in 1097. But they merely agreed that the system of patrimonial

succession should be confirmed. This agreement not only failed to ensure that

struggles for power would be avoided in future, but it also encouraged the

trend toward princes asserting their independence as rulers in their own

principalities, and thus promoted the dismemberment of Kievan Rus.

The death of Svyatopolk II in 1113 spurred the people of

Kiev to action. The veche, medieval Russia’s traditional citizen parliament,

held an emergency meeting and agreed to offer the throne to Vladimir Monomakh,

prince of the southern city of Pereyaslavl and a son of Vsevolod by his Greek

wife (hence the surname Monomakh). This was contrary to the Lyubech agreement,

in accordance with which the son of Svyatopolk should succeed. In making the

decision, the citizens of Kiev had not consulted the metropolitan or the

leading men of the deceased grand prince’s retinue. To select the ruler in this

way was unprecedented, and Yaroslav’s grandson, fearing the armed opposition of

the other princes of the Rurikide dynasty, refused to go to Kiev. On learning

of his decision, the people began rioting in the city. The Church leaders and

the upper class generally became alarmed and sent an urgent message to

Vladimir: “Come, O Prince, to Kiev; and if you do not come, know that much evil

will befall. . . .” Recognizing the danger that revolution would overtake Kiev

and the whole country if he did not accept the throne, Vladimir went to the

city, where he was acclaimed by the metropolitan and the people.

Vladimir Monomakh was a remarkable man. Generous, kind, and

just, he has been called the exemplar of the old Russian prince. The ideals he

pursued were love of God and of fellow man. He cared for the poor, promoted

education, and by all accounts led a blameless life. His “Instruction to his

Children” is a model for liberal, responsible leadership. He directs, in part:

Whenever you speak, whether it be a bad or a good word,

swear not by the Lord, nor make the sign of the cross, for there is no need. If

you have occasion to kiss the cross with your brothers or with anyone else,

first inquire your heart whether you will keep the promise, then kiss it. . . .

Honor the elders as your father, and the younger ones as your brothers. . . .

If you start out to a war, be not slack, depend not upon your generals, nor

abandon yourselves to drinking and eating and sleeping. . . . Whenever you

travel over your lands, permit not the servants, neither your own, nor a

stranger’s, to do any damage in the villages, or in the fields, that they may

not curse you. Whencesoever you go, and wherever you stay, give the destitute

to eat and to drink. Above all honor the stranger, whensoever he may come,

whether he be a commoner, a nobleman or an ambassador. . . . Call on the sick,

go to funerals, for we are all mortal, and pass not by a man without greeting

him. . . . But the main thing is that you should keep the fear of the Lord higher

than anything else. . . . Whatever good you know, do not forget it, and what

you do not know, learn it. . . . Let not the sun find you in bed. . . .”

Vladimir contributed much to the glorification of Kiev. He

also sought to ensure stability within the state, organizing effective defenses

against nomadic invaders from the east, but he was unable to arrest Kiev’s

decline.

Kievan Rus had become vast in

extent, stretching from a frontier about 100 miles south of the city to the

Arctic Ocean. But it had never been more than a loose federation of

principalities. The family of Rurik had grown numerous. As many as sixty-four

principalities could be counted at one stage in the twelfth century. Singly and

in groups, they struggled for power. The rule of Kiev, far to the south, had

depended on the trade with Byzantium and the strength of individual grand

princes. Increasingly the princes to the north had shown reluctance to

acknowledge the supremacy of Kiev. But throughout the country, the practice of

dividing and subdividing principalities to provide an independent udel, or

estate, for each son of each prince had led to fragmentation of principalities

and the creation of countless petty princes who could survive only by expanding

their lands at the expense of their neighbors. Rivalries among the numerous

members of the Monomakh clan over the succession and the control of the great

trade routes had further intensified the princely anarchy, inhibiting the

growth of a sense of nationhood among the Russians. They could not put aside

their rivalries even for the purpose of common defense. The great empire of the

Khazars had long ceased to serve as an eastern shield, and sweeping across the

Eurasian plain, the Pechenegs, the Cumans, and other nomadic tribes came in

increasingly frequent waves. While united under a strong prince, the Russians

had managed to defend their lands, but now they were unable to beat off those

invasions. Moreover, the Germanic tribes were beginning to move eastward,

driving the Lithuanians and Letts before them and presenting another challenge.

Migration to the north had already begun to drain the

strength of Kiev. Novgorod had built up a great commercial empire, extending to

the Arctic Ocean and east to the Urals. It offered security and opportunity to

the Russians, weary of the princely feuds and nomadic attacks in the south.

Many Russians made their way into Galicia and to Belorussia, which were later

to come under the rule of Poland-Lithuania. But the most important wave of

migration was to the northeast, the dense forest lands of the upper Volga and

its tributaries. Here, in the second half of the twelfth century, the foremost

prince was Monomakh’s grandson, Andrei Bogolyubsky of the central Russian

principality of Rostov-Suzdal. An able and energetic ruler, he expanded his

lands and built as his capital the city of Vladimir on the Klyazma River, some

120 miles east of the site that would later become Moscow. In March 1169, his

army captured Kiev and laid waste to the proud city, which never recovered from

this savage blow. The center of the Russian state had moved to the forests of

the northeast, but before the Russians could develop further toward nationhood,

they were overwhelmed by the calamitous Mongol invasion.