Chinese Tactical Leadership.

Chinese junior officers performed equally well, perhaps even

better, than their generals. The Chinese employed a highly decentralized

command system that placed a heavy burden on tactical leaders. Because Chinese

operations were often conducted at night, involved large-scale infiltrations,

had few radios, and placed a premium on stealth, it was often impossible for

senior commanders to direct their forces in the midst of battle. The Chinese

also placed a premium on decisions made on the spot in response to immediate

circumstances. In particular, they emphasized the immediate exploitation of

gaps and weak points such as unit boundaries, which meant that junior officers

were expected to recognize such opportunities and act on them without direct

orders. As one historian observed, “The nature of the Chinese Red Army, with

its paucity of modern military equipment, placed a great deal of responsibility

on unit commanders, they were to follow the general plan if they could, but not

be afraid to deviate if it seemed appropriate.” To facilitate this, the Chinese

army conducted extensive pre-attack briefings, with senior officers providing

remarkable amounts of information to their subordinates to ensure that more

junior commanders would be able to make smart decisions during the battle based

on a full understanding of the plan and the intelligence regarding enemy forces

and intentions. Indeed, virtually all Chinese operations were planned only at

general levels, and the specifics were typically left to the commanders in the

field to decide as the circumstances dictated.

Chinese junior officers performed extremely well in this

system. They kept up a constant stream of patrols to find the enemy, and then

to probe for routes of attack, flanks, gaps in the line, unit boundaries, etc.

Once they had a reasonable picture of enemy dispositions they formulated a plan

of attack and put it into action. They showed tremendous individual initiative

and aggressiveness. They rarely seemed to let an opportunity pass, and reacted

quickly and flexibly to the ebb and flow of combat. At times, they did miss

opportunities to exploit, but typically because their logistics failed them or

they had suffered such heavy casualties taking the position that they had too

little left to follow through. When one approach failed, Chinese junior

officers devised a new plan of action and then put it into effect. They also

showed a real flare for improvisation in their approach to combat situations.

As just one example of this, in 1950 one Chinese company commander had his men

light the dried grass near an American position on fire when they could not

find a way to flank the American lines. The grass burned straight up the hill

the Americans were holding, forcing them to abandon the position.

Chinese tactical units operated at a quick operational

tempo, especially given their lack of motor transport. Chinese junior officers

fully recognized the need to hit hard and fast and to keep hitting the enemy

with rapid blows so that he could not recover. Consequently, they bypassed

resistance when possible and drove as far and as fast into the rear as they

could to overrun command posts and keep the enemy reeling. In one incident,

Chinese troops smashed the ROK 15th Infantry Regiment and then pursued so

quickly that they passed the retreating South Korean troops, overran the

regiment’s command post, and then turned to ambush the combat units (again) as

they fled south.46 Even when one Chinese unit might stop to regroup on an

objective, other elements of the force—or other units of the same

formation—would take it upon themselves to keep moving forward to maintain the

pace of advance and not give the enemy any breathing space.

One of the greatest strengths of the Chinese military at

every level was their predilection for maneuver. Shu Guang Zhang notes that the

PLA itself believed that its forces could overcome American advantages in

firepower because they were “good at maneuvering, flexibility and mobility and,

in particular, good at surrounding and attacking [the] enemy’s flanks by taking

tortuous courses, as well as dispersing and concealing forces.” The PLA’s

favored form of attack—and counterattack—was what Lin Biao referred to as the

“one point, two sides” maneuver, which consisted of a frontal assault to pin

the enemy coupled with a double envelopment. Chinese forces at every level from

army group to squad employed this approach, and when it proved impossible, they

found other ways to maneuver against their foe, performing a single envelopment

or simply attacking from an oblique angle to the defender’s lines. American,

South Korean, Turkish, British (and in 1962, Indian troops) reported being

constantly outflanked and hit from the rear by Chinese units.

These traits were equally apparent in defensive operations.

Chinese tactical commanders were just as diligent about reconnaissance when on

the defensive. They were careful to disguise their positions and built

ingenious defensive networks. Chinese forces were also extremely active on

defense and rarely sat passively in their trenches while being attacked. In

battle, Chinese units would abandon their positions if they thought that they

could move into a better one, preferably one from which they could fire or

counterattack into the attacker’s flank or rear. Chinese units counterattacked

vigorously and quickly at every level. Indeed, many Chinese defensive positions

were designed to lure the enemy in and crush him with a devastating

counterattack (often from several sides simultaneously). Whenever possible, the

Chinese attempted to conduct flanking counterattacks to cut off the attacking

force and crush it. Moreover, if they repulsed an attacker, Chinese units

frequently seized the opportunity to pursue or even launch an immediate attack

of their own.

The Chinese appear to have done adequately in combined arms

operations when their very limited experiences are taken into account. In

Korea, the Chinese initially employed pure infantry formations, but by the end

of the war they also fielded considerable numbers of artillery batteries. By

and large, the Chinese did well in employing their artillery to support their

infantry formations both when attacking and in defense.

Chinese Rank and File Performance. China’s soldiery did all

that could be expected of them. Personal bravery among Chinese units was very

high. The Chinese Army attacked with great confidence and enthusiasm. In Korea,

this remained the case until the cold, the lack of food and other supplies, as

well as the terrifying losses in combat began to set in during 1951. Chinese

unit cohesion was likewise excellent. Although numerous Chinese units did begin

to crack in 1951 at the end of the Fifth Phase Offensive, what was impressive

was just how much hardship and adversity these formations endured before that

happened. By that time, many of the Chinese soldiers were literally starving to

death, clinically exhausted, and numbed by five months of attacks into the

teeth of UN firepower. Most armies would have fallen apart long before.

Chinese weapons handling was mostly poor, albeit with

several bright spots. Chinese marksmanship was lousy across the board. Chinese

infantrymen could do little with their small arms. One exception to this rule

was that Chinese units were often inexplicably good with light machine guns.

Chinese forces also suffered heavily from the limited technical skills of their

personnel. Consequently, few could handle electronics equipment, heavy

weaponry, or other technology-intensive machines. To at least some extent, the

Chinese had to forgo certain weapons that were simply beyond the technical

skills of their men. Moreover, Chinese troops rarely got the maximum

performance out of even the relatively simple weaponry they employed.

By contrast, Chinese artillery and mortar operations were

very competent. Although Chinese forces entered the war with only light mortars

and almost no artillery, by 1952 they had learned to employ their new

Soviet-supplied indirect-fire weapons in a fairly sophisticated manner. As the

war progressed, the ability of Chinese mortar and artillery units to mass their

fire became an important element in their defensive operations. Chinese

artillery batteries could rapidly combine their fire even when geographically

dispersed, their fire missions were often very accurate, and they could quickly

and flexibly shift their fire from one target to the next as required by

front-line commanders. Chinese mortar units even got so good that they could

silence US mortars in counter-battery duels.

Chinese Combat Support and Combat Service Support

Performance. Above all else, logistics was the bane of Chinese military

operations. In Korea, China might have scored one of the most impressive

victories in modern history had its supply services been able to keep pace with

its combat units and had its combat units been able to move faster than they

did. As one historian has said of Marshal Peng, “It was not the Americans who

were defeating him; it was winter, and the Chinese inability to fight this sort

of war on a straight offensive basis. The logistics of an attacking army are

perhaps six times more difficult than those of a defending army, and Marshal

Peng’s logistics, by his own statements, were so ridiculous as to be

laughable.”

The causes of these logistics problems may not be as clear

as they may seem. The most obvious problem the Chinese faced was that they had

too few trucks and trains to supply their army, and too few air defenses to

protect the logistical network from air attack. In addition, they had other

material complications. For example, in Korea, Chinese forces used a multitude

of small arms, none of which were manufactured in China and most of which were

no longer manufactured at all. Consequently, providing ammunition and spare

parts to the combat units was a nightmare. However, it is unclear whether

Chinese logistics problems also were related to China’s low levels of education

or other socioeconomic factors. Logistics for an army that is even crudely

modern requires quartermasters able to read and do arithmetic and often more

complicated mathematics. In addition, supplying such a vast army, over such

great distances with such a multitude of different weapons, is a complex

project to say the least.

Very little information exists regarding China’s maintenance

capabilities. During October and November 1951, the Chinese generally were able

to keep 300–400 of their 800 trucks running on any given day. A 50 percent

operational readiness rate is usually considered very poor, and this would fit

well with the pattern of difficulties the Chinese experienced in other aspects

of military operations related to technical skills. Still, it would be rash to

conclude based on this single scrap of evidence that Chinese armies experienced

considerable problems with maintenance and repairs. The Chinese were using

mostly very old trucks captured from the Guomindang and the Japanese. It is

unclear what kind of shape they were in when the Chinese Communists got them,

or what kind of an inventory of spare parts and lubricants they had by 1950.

Moreover, 800 trucks is an absurdly low number to try to support an army of

over 300,000 men, so those trucks may have been driven to death. For all of

these reasons, this meager evidence on its own cannot support the conclusion

that Chinese maintenance practices were poor, even though this would fit the

pattern suggested by Chinese problems with logistics and weapons handling.

Limited evidence suggests that Chinese combat engineers were

reasonably good. Although the Chinese were known to use infantry battalions to

clear paths through minefields by having them walk across in line-abreast, they

generally could rely on a competent corps of engineers. In Korea, Chinese

engineers built impressive fortifications very quickly. Chinese engineers

showed a tremendous ability to cross water obstacles. The US Air Force was

constantly frustrated by the speed and ingenuity of Chinese engineers building,

repairing, and circumventing bridges knocked down by US air strikes.

Chinese Air Force Performance. China’s air force made a

reasonable effort given its newness. The Chinese did not necessarily do “well”

in any category of air operations, but deserve high marks for learning quickly.

The planning and direction of Chinese air operations was

reasonably good. Chinese Air Force leaders initially recognized that their

squadrons were only capable of defensive counter-air missions, and so they

concentrated on trying to disrupt the US campaign against Chinese logistics.

Later, as the forces available to them improved, they took on more ambitious

missions. The Chinese quickly deduced the weaknesses of the F-86 Sabre,

specifically its limited range, and designed tactics to try to take advantage

of that problem. Although the United States quickly countered, the Chinese in

turn devised a counter to the Americans’ counter-tactic. The United States

ultimately prevailed in this contest, but this rapid interplay indicates that

Chinese Air Force leaders were intelligent, creative, and resourceful and

actively tried to shape aerial encounters, rather than passively accepting

situations as they occurred.

Chinese air forces concentrated almost exclusively on

counter-air missions; consequently, this is the only category of air operations

in which the Chinese performance can reasonably be assessed. The Chinese began

very poorly but had made major improvements by war’s end. The chief factor was

the experience of Chinese pilots. At the start of the war, the Chinese Air

Force was brand new and had only a handful of qualified pilots, none of whom

had participated in air-to-air combat before. When these men went up against

the World War II veterans of the US Air Force they were slaughtered. The

Chinese began sending large numbers of pilots to the USSR for training, and

over time, they began to give the American pilots a harder time. There was

never a month during the Korean War when Chinese MiG squadrons did more damage

to the Americans than they sustained themselves, but by 1952 they had reduced

the number of losses they were taking and had increased the number of US planes

they were shooting down.

Chinese Air Force Performance.

China’s air force made a reasonable effort given its

newness. The Chinese did not necessarily do “well” in any category of air

operations, but deserve high marks for learning quickly.

The planning and direction of Chinese air operations was

reasonably good. Chinese Air Force leaders initially recognized that their

squadrons were only capable of defensive counter-air missions, and so they

concentrated on trying to disrupt the US campaign against Chinese logistics.

Later, as the forces available to them improved, they took on more ambitious

missions. The Chinese quickly deduced the weaknesses of the F-86 Sabre,

specifically its limited range, and designed tactics to try to take advantage

of that problem. Although the United States quickly countered, the Chinese in

turn devised a counter to the Americans’ counter-tactic. The United States

ultimately prevailed in this contest, but this rapid interplay indicates that

Chinese Air Force leaders were intelligent, creative, and resourceful and actively

tried to shape aerial encounters, rather than passively accepting situations as

they occurred.

Chinese air forces concentrated almost exclusively on

counter-air missions; consequently, this is the only category of air operations

in which the Chinese performance can reasonably be assessed. The Chinese began

very poorly but had made major improvements by war’s end. The chief factor was

the experience of Chinese pilots. At the start of the war, the Chinese Air

Force was brand new and had only a handful of qualified pilots, none of whom

had participated in air-to-air combat before. When these men went up against

the World War II veterans of the US Air Force they were slaughtered. The

Chinese began sending large numbers of pilots to the USSR for training, and

over time, they began to give the American pilots a harder time. There was

never a month during the Korean War when Chinese MiG squadrons did more damage

to the Americans than they sustained themselves, but by 1952 they had reduced

the number of losses they were taking and had increased the number of US planes

they were shooting down.

Nevertheless it is still the bottom line that, throughout

the war, the Chinese never performed as well as the Americans in air combat

maneuvering. They fought aggressively, and they maneuvered, and some of their

pilots were able to really exploit the capabilities of their aircraft, but they

were never able to do it at the same level as the Americans. As a result, US

Sabre pilots racked up at least a 5:1 kill ratio against the Chinese for the

war.

Decisive Factors in the Korean War.

Chinese forces did as well as they did in combat for several

reasons. Chinese leadership at both strategic and tactical levels was

unquestionably the most important factor in Chinese successes. China’s generals

did a superb job employing the resources at their disposal to achieve Beijing’s

political objectives. In many of their campaigns, the Chinese achieved

spectacular results that almost certainly would have been beyond the reach of

less competent generals commanding the same forces. Similarly, it is difficult

to fault Beijing’s generals for Chinese failures. Ultimately, the tasks set for

them by their political masters may well have been unachievable.

Chinese tactical competence was just as important as the

skill of their strategic leadership. In battle, the Chinese were an extremely

dangerous foe, and what is so incredible is that they achieved this level of

tactical prowess despite pitiful weaponry and illiterate soldiers mostly

incapable of taking full advantage of the meager equipment they possessed. It

is remarkable that Chinese infantry companies of roughly 100 men equipped with

no more than a few dozen rifles, perhaps three or four light machine guns, and

maybe a light mortar or two, could attack and defeat entrenched American units

of roughly equal size but lavishly armed with the most modern weapons and

backed by fearsome air and artillery support. Chinese tactical formations

maintained a torrid pace of operations, although this inevitably outstripped

what their logistical train could support. Their units displayed this tactical

excellence from squad to division levels, and the credit for this has to go to

China’s tactical commanders. With only a few exceptions, the Americans were

never able to match Chinese tactical skills in Korea, and only were able to

achieve a stalemate through the application of overwhelming firepower to bleed

the Chinese army white—and they could do so only because Chinese logistical

failings prevented them from overrunning the peninsula altogether.

Another important aspect of China’s victories was its superb

intelligence capabilities. In Korea, China won the intelligence war, and in

doing so, went a great distance toward winning the entire war. China’s constant

attention to reconnaissance and its persistent efforts to gather information on

its adversary in any way possible usually gave Chinese military leaders at all

levels an excellent understanding of the adversary they faced. On the other

hand, China’s meticulous attention to operational security and CC&D

prevented their enemies from knowing much if anything about their own

operations. At the grandest strategic level, the Chinese moved over 300,000 men

into Korea without the United States realizing it. At tactical levels, Chinese

platoons and battalions often passed right under the noses of US, ROK, and

other Western units before and during a battle.

Chinese military setbacks were largely the product of two

weaknesses: logistics and weaponry. Chinese deficiencies in supplying and

moving their forces were literally crippling because they led to widespread

starvation and frostbite. In 1950–1951, this failing was unquestionably the

most important factor that prevented China from turning a remarkable victory

into a decisive one.

China’s arsenal was its other great problem. The Chinese

simply lacked the equipment that their adversaries possessed, both in terms of

quantity and quality. The gap between the arms of a US, or even a ROK, unit and

those of comparable Chinese units was immeasurable. Nevertheless, China’s

deficiencies in terms of arms should not be exaggerated: the Chinese armed

forces achieved stunning successes despite this problem, and their defeats do

not seem to have been the result of deficiencies in weaponry. Had the Chinese

been better armed, their operations almost certainly would have been even more

successful, but there is no reason to believe that this would have compensated

for the logistical problems that brought their Korean offensives to a halt.

An important aspect of this issue is whether Chinese

deficiencies in weaponry and logistics were purely the product of their

poverty, or the result of an inability among Chinese personnel to read and

write, to understand machinery, and to handle the complex requirements of a

modern army. Was the problem simply that the Chinese could not afford to build

or buy adequate numbers of modern arms, trucks, and combat consumables? Or, was

the problem that even had Beijing been able to acquire adequate supplies of this

materiel it would have made little difference because Chinese soldiers and

officers would have been unable to employ them properly?

This is a crucial question to understand the impact of

underdevelopment on military effectiveness. If the problem is simply one of

availability, then this says little about the impact of underdevelopment on the

performance of the personnel themselves. Of greatest importance, it would argue

that underdevelopment probably was not a very good explanation for Arab

military ineffectiveness, because in most of their wars the Arab armies had a

surfeit of weapons, mobility assets, and supplies. Unfortunately, very little

evidence is available, and what is available is contradictory. For example, the

poor dogfighting skills of Chinese pilots suggests that the problem was an

inability to fully exploit modern technology. On the other hand, the excellent

machine gunning and artillery skills of Chinese ground forces indicate just the

opposite, that the problem was simply the inadequacy of the available hardware.

As a final note, although China’s enemies have often blamed

their losses on Chinese numerical superiority in manpower, this excuse

unconvincing. In Korea, Chinese quantitative advantages were not great. The

Chinese often had fewer men in the field than the UN forces. Of course, the UN

armies had a much lower “tooth-to-tail” ratio so the Chinese frequently had

more combat soldiers available than did the United States. But these imbalances

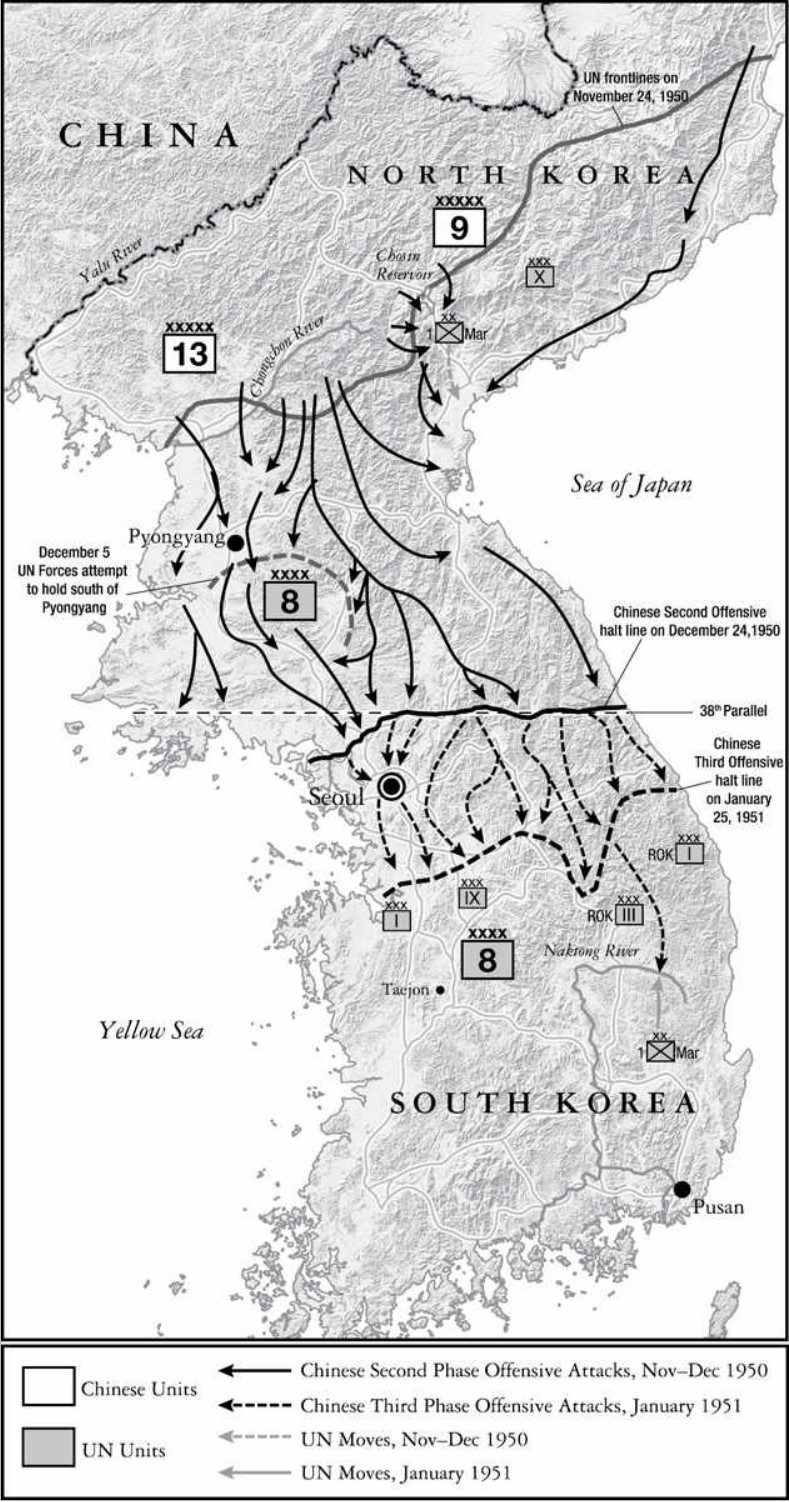

should not have been decisive. For instance, in November 1950, China fielded

388,000 men against 342,000 UN soldiers. Even if one assumes that as much as 80

percent of Chinese manpower were combat troops while only 50 percent of UN

manpower were, the net figure is 310,000 Chinese soldiers against 205,000 UN

soldiers. Given the immense material disparity between the two sides, such a

difference in manpower should not have been decisive. In 2003, an

Anglo-American army of about 75,000 troops with similar material advantages

crushed an Iraqi army of 300,000 and conquered their country in under a month.

If the issue were merely mass versus materiel in Korea, the Chinese advantage

in mass should not have outweighed the UN advantage in materiel.

Regardless of the raw balance of manpower, the crucial point

is that the Chinese did not win by overwhelming numbers. The Chinese were

forced to employ mass as a substitute for firepower in their tactical maneuver

schemes. This should not take away from the fact that their victories over the

US-led armies in Korea were achieved by superior tactical competence. The

Chinese won battles by deceiving, confusing, and outmaneuvering their

opponents, not by drowning them in a sea of manpower. Especially prior to

Ridgway’s reforms, American military units in Korea were very mediocre, and

weren’t even as competent as their World War II antecedents. For the Americans,

having more such units would not have made nearly as much difference as having

more capable ones.

Chinese and Arab Military Effectiveness.

Comparing Arab military performance since 1948 with the

Chinese military experience in the Korean War shows pretty much the same thing

as the Libya-Chad case: vast differences in military effectiveness existed

between many Arab and non-Arab forces despite comparable levels of

socioeconomic development. China’s extreme backwardness does not appear to have

produced the same patterns of ineffectiveness in Chinese forces that

characterized Arab operations during the postwar era.

Aside from those categories related to limited technical

skills, the only areas in which Chinese and Arab armed forces appeared

comparable was in the high degrees of unit cohesion and personal bravery

displayed by both. Other than this, it is difficult to find areas in which the

Arabs fought as well as, or even just similar to, the Chinese. In particular,

the Chinese manifested none of the problems the Arabs had with information

management and tactical leadership in terms of initiative, creativity,

flexibility, responsiveness, etc. Instead, these were areas in which the

Chinese excelled. For the Chinese, maneuver warfare and information management

were arguably their greatest strengths, whereas for the Arabs these were their

greatest weakness.