The Lancaster, anchored above the fleet with some steam up,

claimed to be the first to see the danger. Colonel Ellet signaled the ship to

attack the rebel ram. “As she rounded to give her a little of our kind of

warfare, a 64 pound ball came through our bulwarks and steam drum,” a

correspondent told readers. “Our lead engineer, John Wybrant, was knocked down

and badly scalded inwardly; second engineer, John Goshorn, badly scalded,

jumped overboard, and missing.” Enemy fire also injured three soldiers and seven

black deckhands and coal heavers. “One contraband had both arms and a leg shot

off, badly scalded besides; he died a few minutes later.”

From the Richmond, Commander Alden could see the Lancaster

just astern. The scalded men “jumped overboard, and some of them never came to

the surface again,” he recalled. Ten or twelve men began swimming, but some

just held on to the rudder. The Lancaster ordered a boat to rescue the men, but

according to Alden, “By this time she had drifted astern of us, and the ‘Arkansas’

came on down, and as she passed we fired our whole broadside!” One shot knocked

Brown off the platform where he stood, breaking a marine glass in his hand.

Without flinching, Brown resumed his place directing the ram’s movements. When

a seaman called out that the colors had been shot way, midshipman Dabney Scales

dashed up a ladder, ignoring a hail of fire, to bend on the colors again.

Keeping to midstream, the Arkansas ran the gauntlet of federal vessels anchored

on either side and seemingly escaped damage. The Richmond fired a broadside at

the ram, which momentarily disappeared in the smoke. The Hartford’s gunners

eagerly watched for the smoke to lift so they could take a shot, but the

Arkansas passed by the flagship and then turned to. Suddenly, when it was a

half mile astern, the Arkansas fired two shots at the flagship, which missed,

and the ram steamed downriver.

“The fleet kept up a brisk fire on her as she passed with

all the guns practicable,” the Cincinnati’s O’Neil explained. “Our fire was,

however, necessarily limited owing to the great danger of hitting our

Transports ranged along the bank.” The Cincinnati, below the fleet on picket

duty, still kept its position. The ram steamed off toward the Cincinnati “as if

going to ram us, but probably finding the water too shoal for her continued on

her former course. We opened a heavy fire on her, with apparently good effect

and which she returned.”

When the Arkansas came to the end of the line of enemy

ships, Brown recalled, “I now called the officers up to take a look at what we

had just come through and to get the fresh air, and as the little group of

heroes closed around me with their friendly words of congratulations, a heavy

rifle-shot passed close over our heads; it was a parting salutation, and if

aimed two feet lower would have been to us the most injurious of the battle.”

To Farragut’s “mortification,” the battered Arkansas steamed on to the

Vicksburg wharf and the protection of the Confederate batteries.

The Arkansas had “successfully run through a fleet of

sixteen men of war, six of them ironclad, and mounting in the aggregate not

less than one hundred & sixty guns,” O’Neil commented. “A far more

brilliant achievement than that accomplished by the ‘Virginia’ at Hampton

Roads.”

Visibly shaken by the rebel ram’s success, Farragut

immediately called for a conference with Davis. In the Hartford’s cabin the

flag officer told Davis that he intended to have his fleet raise steam and

immediately go down to destroy the ram. Davis tried to dissuade the irate

Farragut from this rash and dangerous action, arguing that the Arkansas was

comparatively harmless where it was. When Davis declined to attack the ram,

Farragut reluctantly agreed to wait until late afternoon to run past the rebel

batteries. Davis then returned to his flagship.

The soldiers and citizens of Vicksburg greeted the

Arkansas’s arrival with shouts of joy. General Van Dorn dashed off a telegram

to President Jefferson Davis, announcing the ram’s safe arrival and assuring

him that it would “soon be repaired, and then ho! for New Orleans.”

Late in the afternoon the rumble of thunder and a cool

breeze announced the arrival of a storm. The ensuing rain and wind delayed the

fleet’s preparation to run past Vicksburg, but just before 7:00 p.m. Farragut’s

ships got under way in two columns. Farragut’s parting signal left no doubt

about their mission: “The ram must be destroyed.” Davis sent the Sumter down to

Farragut and instructed the Benton, Louisville, and Cincinnati to draw fire

from the upper rebel battery.

Darkness fell as Farragut’s ships neared the upper battery.

When the Confederate gunners opened fire, the Hartford’s gun crews returned

fire, aiming at the gun flashes. As the ship approached the enemy, shot and

shell began whistling overhead. Several enemy shots struck the flagship’s hull,

and one 9-inch shell carried away the starboard fore-topsail bitts on the berth

deck but did not explode. Marines stood by their gun and did not suffer any

injuries, but they heard the disturbing news that their commanding officer,

Captain John Broome, had suffered a bruised head and shoulder. He would

recover, but master’s mate George Lounsberry; Charles Jackson, the officers’

cook; and seaman Cameron were killed by a cannonball. Six others were wounded.

Passing the rebel battery had inflicted a few casualties on

the crews of the Richmond, Sciota, and Winona as well. A shell explosion killed

one man on the Winona, and to keep it from sinking, the ship had to be run on

shore.

As Farragut’s port column passed just thirty yards from

shore, he strained to see the rebel ram in the darkness but could only make out

the enemy’s gun flashes. Lee claimed he had seen the Arkansas lying under a

bank in an exposed position and had fired two solid shots at it from the

Oneida’s 11-inch pivot guns.

When Farragut’s vessels returned, Bell, now commanding the

Brooklyn, boarded the Hartford and found a dispirited Farragut. They had not

destroyed the rebel ram, and Farragut’s fleet had suffered five killed and

sixteen wounded. Davis’s squadron had thirteen killed and thirty-four wounded.

Bell recalled that Farragut vented his anger and disappointment, saying, “The

ram must be attacked with resolution and be destroyed, or she will destroy us.”

That evening, one of the Hartford’s officers put pen to

paper and wrote a letter to his family. “The fight was a hard one,” he told

them, “and the firing on both sides was terrific. . . . Our decks were

slippery, and in some places, fairly swimming with blood.” He revealed that in

the morning he would have to bury a shipmate. “I hope and pray this war may

soon be ended; but God’s will be done. This rebellion must be crushed if it

costs the life of every loyal citizen in the country. The ram can be seen lying

off Vicksburg, and it is expected that she will come down. But we are ready for

her now, and will not be caught napping again.”

The morning of July 16 dawned cold and rainy. “Some of our

missing has turned up and report three of their number drowned in endeavoring

to swim ashore,” the Carondelet’s Morison wrote. “Our dead were taken ashore at

noon and burned. A great many of our crew sick with the ague. In fact, all

hands look dull and stupid.” Many of the Hartford’s crew had taken ill as well.

“Half of the marine guard is on the medical list,” Private Smith noted. “Fifty

odd are on the list.” The Carondelet remained with the fleet for several days,

awaiting repairs to its steam pipes. “The number of our sick still increasing,”

Morison reported, “the captain being amongst the number.” On Sunday he

delivered a message to Walke, who had gone to the hospital boat Red Rover that

morning. “Saw some of our wounded and sick. All seemed to be doing well. Found

that some ‘Sisters of Charity’ were stationed on the boat and all the patients

spoke very highly of their patience and self-denial.”

On July 21 the Carondelet began taking on coal for the

journey to Cairo. “Thirty contrabands were sent to coal her and help work her

to Cairo,” Morison wrote. He was put in charge of some of the contrabands “to

see that they worked and to remain until the job was finished.” Supervising the

coaling kept Morison up until 3:30 a.m., when he got his grog and turned in for

a short nap. The next day, “the first cutter also brought whatever of our sick

were able to stand the journey to Cairo. Twenty five of the contrabands were

kept on aboard, the remainder being sent back to their quarters about 2 P.M.

Carondelet then got under way and headed toward Cairo.”

Still smarting from his failure to destroy the Arkansas,

Farragut gathered Bell, Alden, De Camp, and Renshaw the following morning for a

conference. He proposed to take the three larger ships and attack at night.

Bell wrote in his journal, “I was opposed to the night attack for the reason

that the one just made was a failure; that a low object against the bank could

not be seen.” Bell favored a daytime attack, and Alden agreed, suggesting that

Davis’s ironclads and rams be given the mission. According to Bell, Farragut

responded that he could not control Davis’s ships and could trust only his own

vessels.

Now determined to attack the Arkansas during daylight,

Farragut ordered preparations made and the Sumter fitted out to ram the rebel

ironclad. On July 16 the Arkansas moved into the river, turned, and went back

to the Vicksburg wharf, as if taunting the federal fleet. Farragut fired off a

message to Davis, reminding him that the country would blame both of them for

any disaster that occurred if the ram escaped. He proposed a combined attack on

the rebel ram. Farragut promised his full support if Davis would come down with

his ironclad vessels past the first enemy battery and meet him off Vicksburg to

fight both the batteries and the ram.

In his usual calm, thoughtful manner, Davis replied to

Farragut’s proposed attack by arguing that the Arkansas was “harmless in her

present position” and would be more easily destroyed if it came out from under

the protection of the batteries. Explaining that he was as eager as Farragut to

“put an end to this impudent rascal’s existence,” Davis advised vigilance and

self-control, “pursuing the course that was adopted at Fort Columbus, Island

No. 10, and Fort Pillow.” After reading Davis’s reply, Farragut called for

another council with his commanders, explaining that he had tried to prod Davis

into action, sending him two more messages suggesting that a few shells might

disturb the people at work on the ram, but Davis refused to move.

This council of war resolved nothing, and the Arkansas

remained off Vicksburg, an ever-present reminder of Yankee ineptness. For days

Farragut and Davis engaged in a back-and-forth debate on a course of action to

destroy the Arkansas, but they were unable to resolve their differences. On a

scorching hot July morning, Farragut crossed the peninsula to see Davis, who

informed him that Colonel Ellet had agreed to have one of his rams attack the

Arkansas if the navy would attack the batteries. Chagrined at his rams’

inability to resolve the situation, Ellet had written to Davis on July 20,

arguing that the Arkansas’s presence “so near us, is exerting a very pernicious

influence upon the confidence of our crews, and even on the commanders of our

boats.” He urged that some risk be taken to destroy the ram and to

“re-establish our own prestige over the Mississippi River.” Farragut then

reconsidered Ellet’s proposal to have Davis’s fleet engage the Confederate

batteries while he sent one of his rams to attack the Arkansas at the wharf.

An article in the Cincinnati Daily Gazette offered

additional details about the plan. On Monday morning, Davis, Farragut, and

Ellet had met for an hour on board the ram Switzerland, the newspaper claimed,

where Ellet’s daring plan “was fully discussed and explicitly agreed upon.”

According to this article, “The Commanders agreed that the Essex which is

regarded as little less than invulnerable, should go ahead of the ram and

attack the Arkansas, grapple her, and so distract her attention as to give the

ram the least possible opportunity of butting her.” Ellet agreed to furnish the

Queen of the West for the enterprise, which was set to commence the next

morning, July 22, at daybreak.

The success of the attack depended primarily on Davis’s

flotilla, especially Porter’s ironclad Essex and Ellet’s ram Queen of the West.

Davis’s fleet would bombard the upper batteries at Vicksburg, while the lower

fleet under Farragut attacked the lower batteries. “The Essex was to push on,

strike the rebel ram, deliver her fire, and then fall behind the lower fleet,”

Porter explained. With the Sumter in the lead, Farragut’s vessels would get in

position to cover the lower Confederate batteries and await the Arkansas, which

Davis expected would be driven down or destroyed by the shot-proof Essex. Davis

wanted the Sumter to attack and ram the Arkansas as well, and he rejected a

last-minute message from Farragut suggesting that his fleet come up past the

lower batteries to assist.

The Essex took on coal and sent its crew ashore to fill

sandbags, which were packed on the upper deck over the boilers. The Louisville,

Cincinnati, Benton, and Bragg also prepared for the attack. Ellet selected a

volunteer crew for the Queen of the West “and told his men in plain terms that

he wanted no man to accompany him that was not ready to risk his life in the

project.”

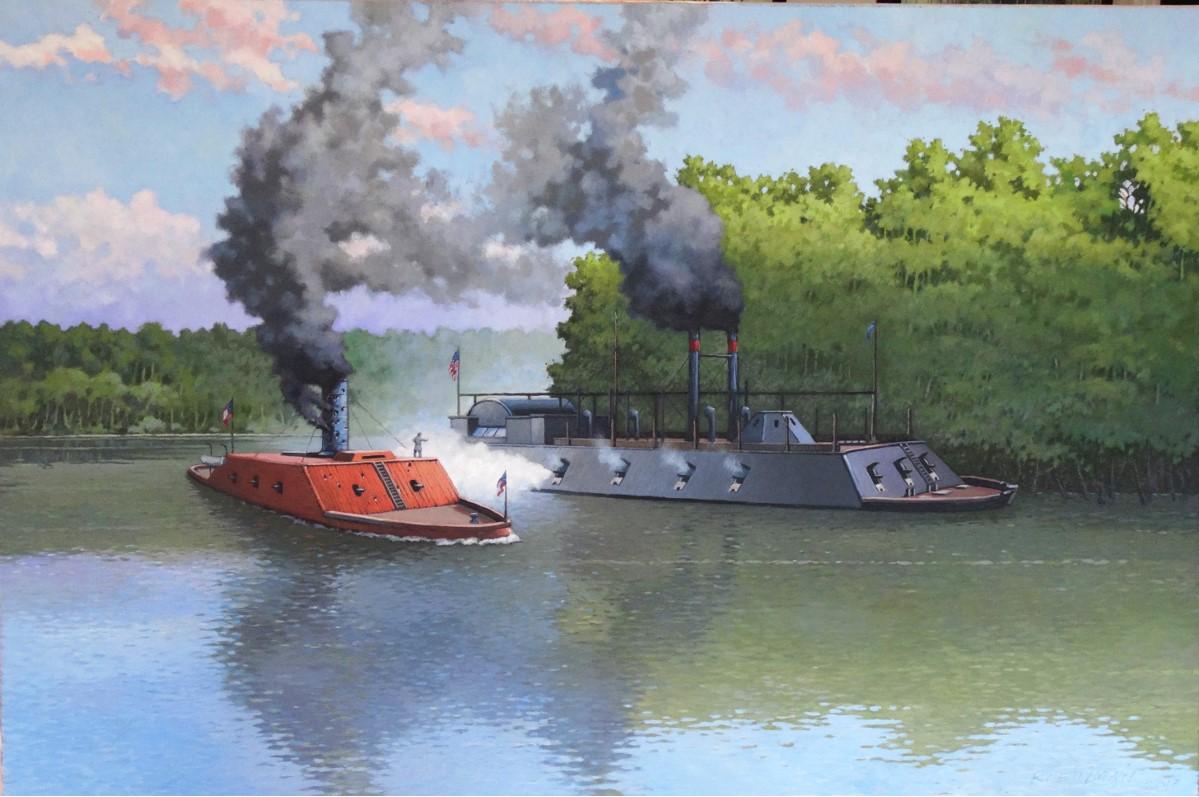

On Tuesday morning, July 22, Davis’s three gunboats, the

Benton, the Cincinnati, and the Louisville, steamed down the Mississippi to

shell the upper rebel batteries as the Essex and the Queen of the West got

under way to make their assault on the Arkansas, which was moored that morning

to the riverbank with its head facing upriver. “We were at anchor with only

enough men to fight two of our guns,” Brown recalled, “but by the zeal of our

officers, who mixed in with these men, as part of the guns’ crews, we were able

to train at the right moment and fire all the guns which could be brought to

bear upon our cautiously coming assailants.”

In his recollections of the engagement, Lieutenant George W.

Gift wrote, “In a few minutes we observed the ironclad steamer Essex steaming

around the point and steering for us.” As the Essex and Queen approached the

upper battery, the rebel gunners opened fire. The ram took aim at the Essex

with its Columbiad, but the Essex pressed on toward the Arkansas. Gift’s gun

crew got off a shot that struck the federal ironclad, but “on she came like a

mad bull, nothing daunted or overawed.” Watching the Essex head toward his

vessel, with the Queen of the West following, Brown realized that Porter’s plan

was to have the Queen run into the Arkansas with its flat bow and shove it

aground so that his ram could butt a hole in Brown’s ram.

Porter did just as Brown expected. He brought the Essex

abreast of the Arkansas, turned, and attempted to ram the rebel amidships.

Brown, however, had cut the bow hawser, hoping to let the current swing the bow

toward the federal ironclad. Every minute counted, and with its speed decreased

by the turn, the Essex missed the lethal, pointed ram and slammed into the

Arkansas at an angle. “At the moment of collision, when our guns were muzzle to

muzzle,” a shot from one of the Essex’s bow guns struck the Arkansas a foot

forward of the forward broadside port, “breaking off the ends of the railroad

bars and driving them in among our people,” Brown wrote. The shot crossed the

gun deck and hit the breech of a starboard gun, cutting down eight of Brown’s

men and wounding six more. Splinters flew in every direction. As Porter brought

the Essex alongside the Arkansas, the ram poured out a broadside. Brown went

ahead on the port screw, turned, and brought his stern guns to bear. In the

face of murderous fire from rebel batteries and riflemen, some of them only 100

feet away, Porter’s men could not board the Arkansas, so he ordered the Essex

to back off and drift downstream.

On the Queen of the West, correspondent Dungannon had a

ringside seat for the encounter with the rebel ram. He watched the Essex about

a mile ahead of him reply to the rebel’s fire and then speed past. “This

disconcerted Col. Ellet considerably for he expected to find the iron-clad vessel

in close quarters with the rebel gunboat. Just at this critical moment, too,

the Flag-Officer Davis waved his hand from the Benton, to Ellet and shouted,

‘Good luck, good luck!’ which Ellet understood to be, ‘Go back Go back!’ and

immediately gave orders for the engines to be reversed.” When Ellet realized

his mistake, he ordered the Queen to head for the Arkansas, which lay with its

prow upstream. Ellet and his son Edward stood on the upper deck of the Queen of

the West, and as it approached the Arkansas, a shower of bullets from

sharpshooters along the shore whistled around their heads. The sound of

shattering hull timbers followed as the rebel ram fired its forward and

larboard guns. Dungannon braced himself as the ship struck the Arkansas just

aft of the third gun on the port side. Delayed by the confusing signal, the

Queen of the West managed to strike only a glancing blow on the Arkansas,

stripping some of its railroad irons half off but not seriously damaging the

ram. The Queen of the West drifted astern, pummeled by fire from the rebel ram,

and Ellet saw that he faced a “fiery gauntlet of a mile of batteries to be

run.” Newsman Dungannon gave the colonel credit as a “courageous commander” who

“nerved himself to the terrible task,” coolly giving orders for the direction

of his vessel and finally reaching the turning point in safety, “amid a perfect

hurricane of shot and shell.”

To cover the run past the batteries by the Essex and Queen

of the West, the gunboats Benton, Cincinnati, and Louisville had engaged the

upper rebel batteries. According to O’Neil on the Cincinnati, “In this

engagement our upper works were badly cut up, but no one on board was injured.”

Damaged but still afloat, the Arkansas slipped away

upstream. The contest with the Essex had been so close that unburned powder

coming through the ram’s gun ports had blackened and burned the faces of some

of the surviving crewmen. And, to Gift’s astonishment, he discovered the ram’s

forecastle littered with hundreds of unbroken glass marbles—the kind boys play

with—fired from one of the Essex’s guns. The Essex and Sumter fled downstream,

now cut off from Davis’s command. To Davis’s consternation, the Sumter had not

participated at all.

This failed attempt to destroy the Arkansas brought recriminations

from all sides. Ellet laid the blame on Davis, who in turn pointed the finger

at Farragut. Davis argued that Farragut had not cooperated with his efforts

above the upper batteries and had withheld his squadron’s support. Nettled,

Farragut defended himself, reminding Bell of the letter received from Davis the

night before the battle in which “he specifically told me that the lower fleet

were to have no share in the affair until the ram was driven down to us.”64

Davis focused his displeasure on the Sumter, which had

failed to come up. In a petulant letter to Foote, Phelps argued that Farragut

should have advised the Sumter’s commander that his plans had changed and

allowed him to act independently. “Because the lower fleet failed to act the

whole affair failed of its purpose though the attempt was a gallant one,”

Phelps told Foote. “The whole thing was a fizzle. Every day we heard great

things threatened only to realize fizzles.” Phelps was not optimistic about the

situation of the lower flotilla: five of the thirteen vessels were undergoing

repairs, 40 percent of the men were sick, and the vessels on the river were

being fired on by enemy batteries. Amidst all this, the officers and men of the

two squadrons could agree on only one important fact: the second attempt to

take Vicksburg had failed dismally.

With the water level in the Mississippi falling, threatening

to strand his larger vessels, Farragut was eager to move downstream, so he

welcomed a telegram from Welles the next day that read: “Go down river at

discretion. Not expected to remain up during the season.” Farragut then called

Bell, Alden, Lee, and Crosby to the flagship for a council, informing them that

the Navy Department had given him permission to go downriver. The Arkansas

still posed a threat, but former fleet captain Bell argued that mounting

another attack with so many vessels in need of repair and so many men sick

would be inadvisable. When all his commanders had spoken their mind, advising

him to abandon the pursuit of the Arkansas and the Vicksburg operation,

Farragut dismissed the four officers and sat down to pen a letter to Welles. He

told the secretary that to attack the ram “under the forts with the present

amount of work before us would be madness.”

The following day, July 24, as the thermometer climbed

toward ninety degrees, Private Smith watched from his station on the forecastle

as Farragut’s ships weighed anchor. “At two o’clock the whole fleet got in line

and proceeded down the river. The river boats carry the troops and also tow the

mortar schooners. The Richmond, Hartford and Brooklyn bring up the rear, the

Brooklyn last.” No one regretted leaving Vicksburg and its debilitating

climate, especially Farragut. Left behind were the slaves who had toiled in the

heat and malarial swamps to dig the canal, denied their promised freedom. Their

frantic, tearful pleas to be taken on board fell on deaf ears but tugged at the

heartstrings of the bluejackets who had shared the arduous work with them.

Farragut intended to drop Williams’s troops off at Baton Rouge and then take

his fleet into the Gulf of Mexico.

Farragut was relieved to be leaving Mississippi’s infernal

heat and mosquitoes, but he remained despondent over his failure to destroy the

Arkansas. In his diary, Welles expressed his own opinion of the saga: “The most

disreputable naval affair of the War was the descent of the steam ram Arkansas

through both squadrons till she hauled in under the batteries of Vicksburg, and

there the two flag officers abandoned the place and the ironclad ram, Farragut

and his force going down to New Orleans, and Davis proceeding with his flotilla

up the river.”

With the lower fleet gone, Davis had decided it would be

safe to send his squadron away from Vicksburg. With 40 percent of his men ill

with malaria and scurvy, Davis knew he had to move to a healthier climate. In

his diary he wrote, “Sickness had made sudden and terrible havoc with my

people. It came, as it were, all at once.” A request for gunboats from General

Samuel Curtis at Helena, Arkansas, offered further enticement, and Davis knew

his withdrawal “would not involve any loss of control over the river.” Davis

explained that he could not have taken Vicksburg without troops, and “this

being so I am as well at Helena as at any point lower down.” Recent reports

from transports and towing vessels confirmed that if Davis had remained at

Vicksburg any longer, he would not “have had engineers nor firemen enough to

bring the vessels up. As it is we have depended very much on the contrabands to

do the work in front of the fires.” A reporter also noted, “It has become an

absolute necessity to employ negroes in almost every capacity in the flotilla,

for they alone seemed adapted to endure the rigors of this plague-infested

atmosphere.”

Illness had deprived Ellet of many of his men as well, and

he told Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that he had “to employ large numbers of

blacks, who came to me asking protection.” Some of these were the African

Americans employed by General Williams and left on the Louisiana shore. Stanton

instructed Ellet to employ “such negroes as you require on your boats, and send

the others who are under your protection to Memphis to be employed by General

Sherman.”

Struggling against the current, the flagship Benton, assisted by the General Bragg and the Switzerland, made it to Helena on the last day of July. After only a few days, however, Davis decided to go to Cairo, leaving Phelps in command at Helena.

1862, CSS Arkansas is destroyed by Cmdr. Isaac N. Brown, CSN, to prevent her capture by USS Essex.