Gentlemen, in seeking combat as we now do we must win or

perish.

—Lieutenant Isaac Brown

The officers and men of Farragut’s fleet, anchored above

Vicksburg, were at breakfast on Tuesday, July 1, 1862, when Charles Davis’s

squadron hove into sight. Winona crewman O’Neil noted its arrival in his diary:

“At 6:25 a.m. during a thunder storm Capt. Davis’ ironclads Benton (F.S.)

Cincinnati, Carondelet, Louisville came down river with steamers towing mortar

boats.” Farragut had asked Davis, who had recently been appointed the flag

officer in command of US naval forces on the Mississippi and its tributaries,

to assemble all the vessels he could, steam down from Memphis, and join him in

reducing the Confederate defenses at Vicksburg.

Word spread quickly, and Farragut’s men rushed to the decks

to see the strange new river craft of Davis’s flotilla. Marine private Smith’s

duty on board the Hartford gave him an opportunity to see Davis’s arrival.

“Today has been an eventful day,” Smith penned in his diary. “The marines fell

out and saluted Commodore Davis when coming and going. Captain Davis dined with

our Commodore and left the ship at 1:15 o’clock.”

When the Carondelet came to anchor, coxswain Morison caught

his first glimpse of Vicksburg. “From where we were lying the dome of the

courthouse and the spires of two churches are to be seen. The Louisiana shore

in front of the city assumes the form of two sides of a triangle (owing to the

sinuous course of the river).” Morison also observed the position of Porter’s

mortar boats. “Along the lower side Porter’s mortars are placed, and along the

upper are ours, so that the city is placed between two fires which must

eventually drive them out.”

The joining of these two federal squadrons gave rise to loud

cheering from Farragut’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron and joyous celebrations

by both officers and enlisted men. Most of the officers of the two squadrons

had been shipmates before the war, and they welcomed the opportunity to catch

up on war news and family events. However, it soon became apparent that all was

not well with Farragut’s squadron. “There’s a great deal of gossip among the

officers,” Phelps explained in a letter to Foote. “The lower fleet is rent with

criminations and recriminations.”

Bell confided his distress about the situation to his

journal. “Visited the fleet below. Bad state of feeling there. C—had received a

sharp reprimand from flag-officer, which he considered unmerited and insulting,

and would not be comforted.” Farragut informed Bell that he was to replace

Craven and assume command of the Brooklyn. “This is a heavy blow, and

interferes with my calculations for getting free of the river, for there is

every prospect of the fleet summering between its steep banks, smitten with

insects, heat intolerable, fevers, chills, and dysentery, and inglorious

inactivity, losing all that the fleet has won in honor and reputation.” The

word of Craven’s departure spread quickly among the crews of both fleets. Bell

reluctantly packed his uniforms and personal gear and made a brief but poignant

entry in his journal: “Found an order for me to relieve Captain Craven in command

of the Brooklyn; went to bed with a heavy heart.”

Farragut’s requests that Halleck send troops to attack

Vicksburg had gone unanswered, leaving only Williams’s 3,000 troops to take the

Confederate stronghold defended by 12,000 rebels. Halleck could have committed

his entire federal force to the taking of Vicksburg before leaving for

Washington to replace George McClellan as general in chief, a change in command

prompted by McClellan’s humiliating defeat before Richmond. Instead, Halleck

chose to dismantle “his grand army piecemeal.” He sent Buell’s Army of the Ohio

eastward toward Chattanooga, sent Grant’s Army of the Tennessee west to occupy

Memphis, and recalled Pope’s army to defend Corinth.

Too few to mount a direct assault, Williams’s soldiers,

assisted by a large number of slaves, were put to work digging a

twelve-foot-wide canal across the peninsula opposite Vicksburg. But in the hot,

dry summer weather, the Mississippi River continued to fall, and prospects for

the canal project’s success dwindled.

Without the means to assault Vicksburg, Farragut had to rely

on a bombardment of rebel defenses by his mortars and four mortar scows sent

down by Davis. “Our mortars opened on the city this morning,” Morison wrote on

July 3. “It was soon returned in the shape of a large rifled shell which came

whirling through the air like a gigantic quail. Burst short, doing no harm. The

firing was carried on by both parties at intervals all day. No harm to our

side.”

At midnight, thirty-four guns from the big mortars began a

Fourth of July greeting. They were joined by all the vessels of the fleet

except for the Richmond. That ship’s sick bay and all available spaces had been

taken up by the growing number of ill sailors, most of them suffering from

chills, fever, and dysentery. On the morning of July 4, O’Neil wrote, “8 a.m.

dressed ship as did the other vessels in the fleet in honor of the day.”

Lending a sense of patriotic festivity to the day, several army bands toured

the fleet in boats, playing national airs. Each federal ship flew a large

American flag at the masthead in celebration of the Fourth. “Independence Day.

We are fighting today for what we fought eighty-six years ago—our national

existence then against King George, now King Cotton,” Morison quipped. In honor

of the glorious Fourth, “the main brace was spliced on board every craft of the

two fleets,” he noted, “with the exception of this one miserabile.”

Farragut and Davis celebrated the holiday by going

downstream in the Benton to reconnoiter the Confederate batteries. A formidable

gunboat armed with seven 32-pounders and two 11-inch and seven 8-inch rifles,

the Benton could challenge the rebel batteries, in Davis’s opinion. But to his

surprise, when the gunboat opened fire on the upper battery, the rebels shot

back with a new Whitworth rifle. One shot went clean through the Benton’s bow

gun port, exploding with a bang and injuring several sailors.

Much as Bell had feared, the hot summer of 1862 continued to

generate a steady supply of sick soldiers and sailors. On July 9 a

correspondent reporting from Farragut’s fleet off Vicksburg told readers:

“Considerable indisposition prevails among the fleet, chiefly arising from the

excessively hot weather. Bowel complaints, and various forms of bilious

diseases affect all, more or less, but no deaths occur from these causes.” In

his diary Bell noted the prevalence of illness: “A large sick list, the cases

being a type of dengue fever (fever and chills).”

Federal gunboats plying the Mississippi also had to contend

with rebel guerrillas lurking along the shore and taking potshots at passing

vessels. A correspondent on board the ram Queen of the West, en route from

Memphis to join the flotilla at Vicksburg, told readers: “Occasionally along

the shores the dreaded guerrillas stealthily gliding from tree to tree, with

the deadly intent of ‘picking off’ some of our crew, but the bright muzzle of a

brace of 12 pound howitzers flashing defiance from the hurricane deck

admonished the reptiles of terrible retribution.” The correspondent reported

that they had met the ram Lancaster on its way up, and “she had fired into a

band of guerrillas a few miles further down, wounding some and causing all to

scatter.”

Off Vicksburg, Farragut and Davis’s men sweltered in the

heat, pestered by swarms of mosquitoes. Canvas awnings draped over the

gunboats’ spar decks provided some relief from the broiling sun, but the

iron-plated decks shimmered with the heat. On July 13, a Sunday, Morison noted

in his journal: “Am twenty-four years old today and the hottest this summer,

the glass standing at 110 degrees in the shade.” Desperate to ease the

suffering of a growing number of sailors with prickly heat, the Benton’s

surgeon ordered them bathed in vinegar, and soon the pungent odor permeated the

entire gunboat.

With the river level steadily falling, numerous men

succumbing to illness, and his coal and provisions dwindling, Farragut began to

despair. On July 4, confiding his frustrations to Welles, he wrote that he had

“almost abandoned the idea of getting the ships down the river unless this

place is either taken possession of or cut off.” Less than a week later,

Farragut received a telegram from Welles, asking him to send twelve mortar

boats and the Octorara with Porter to Hampton Roads. Porter wasted little time.

He left Commander Renshaw in the Westfield with the remaining mortar vessels

and departed the following afternoon. Porter ordered the vessels’ shot holes

patched and painted over to conceal any damage. Then, with his officers

resplendent in their full dress uniforms and the enlisted men dressed in

whites, Porter took his mortar schooners downstream in parade formation, past

the curious Confederate onlookers lining the riverbanks to watch what they

called a “retreat.” The following day, a Thursday, O’Neil received an

appointment “as an Acting Master in the U.S. Gunboat Service” and was ordered

to report to the USS Cincinnati. He bid his shipmates on the Winona farewell

and joined the city-class gunboat, where he took the morning and dog watches on

Saturday, July 12.

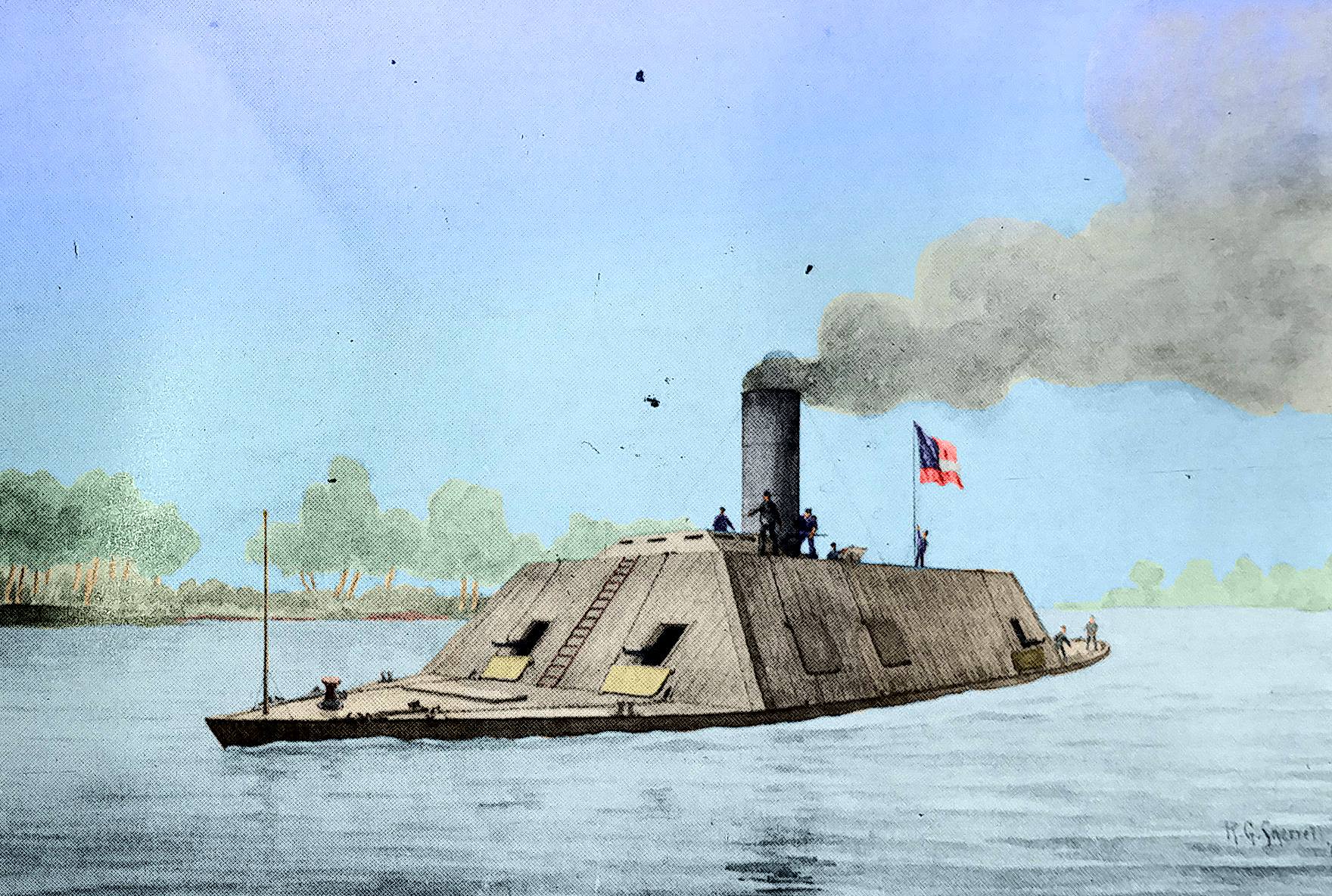

The meeting of Davis’s flotilla and Farragut’s fleet above

Vicksburg had forced the Confederate commander, General Van Dorn, to reassess

the city’s defenses. He then made a straightforward choice, ordering that the

ram Arkansas be completed, put under his orders, and sent to attack the Yankee

fleets. “It was better to die in action,” he argued, “than to be buried up at

Yazoo City.” The ram’s new commander, Lieutenant Isaac N. Brown, a

forty-five-year-old navy veteran from Kentucky, had towed the unfinished vessel

down the Yazoo River from Greenwood to Yazoo City. There, Brown pressed ahead

with almost superhuman effort to turn the hulk into a powerful ram. He procured

workmen and supplies to finish the vessel, which had been labeled a “bucket of

bolts” by its crew, in part because Brown had plated its 18-inch-thick wooden

casemate, which sloped at a 45-degree angle, with railroad iron. The 165-foot

Arkansas had a lethal 16-foot-long ram, two 9-inch smoothbores, two

64-pounders, two 7-inch rifles, and two 32-pounder smoothbores for armament. A

pair of unreliable low-pressure engines salvaged from the sunken Natchez

powered its twin screws, giving the ram a speed of 8 knots, but with a 12-foot

draft, even Brown doubted the ram’s suitability for the West’s shallow, narrow

rivers.

On July 14, ordered into action prematurely, the Arkansas

and its 100-man crew started down the Yazoo, stopping at Satartia to dry powder

from the forward magazine that had been dampened by steam from the old, leaky

boilers. The next day, which one of the sailors described as “bucolic, warm and

calm,” with good visibility, the Arkansas approached the Old River channel near

the Mississippi with the men at battle stations.

Late the previous evening, Phelps had come aboard the

Carondelet to deliver what Walke later described as “formal, brief, and verbal”

orders from Davis to make a reconnaissance up the Yazoo the following morning.

Walke, who had been plagued by a fever off and on, replied that many of his

crew were ill, and he could man only one division of guns. Brushing aside

Walke’s objections, Phelps explained that based on information from deserters,

the rebel ram would come down on July 15. Davis had dismissed these reports

earlier, but now, Phelps felt, Davis believed them.

The Carondelet departed before dawn the next morning, and

two hours later, with a pilot on board, it entered the Old River. To Walke’s

surprise, he spotted the faster Tyler and Queen of the West passing him. They

steamed a mile or so ahead of Walke’s ironclad. At about 7:00 the call “Boat in

sight” interrupted the Tyler crew’s breakfast of coffee and hard biscuits.

Squinting in an attempt to make out the vessel’s identity, the Tyler’s pilot

exclaimed, “Looks like a ‘chocolate brown’ house.” The captain, Lieutenant

William Gwin, focused on the steamer’s huge smokestack through his spyglass and

immediately recognized the vessel as the rebel ram Arkansas. Through the ram’s

two gun ports, Gwin could clearly see heavy guns. “The ram not having any

colors flying, we fired a shot at her,” Gwin wrote in his initial report.

From the ram’s shield, Brown saw the federal timberclad and,

in the light of the rising sun, two more vessels. Gathering his officers, he

said, “Gentlemen, in seeking combat as we now do we must win or perish.”

Admonishing them to fight their way through the enemy fleet and on no account

allow the Arkansas to be taken by the Yankees, Brown told them, “Go to your

guns!”

A puff of powder, followed by a cannonball whizzing over the

pilothouse, prompted Gwin to order the Tyler’s forward gun deck to open fire on

the rebel ram. From half a mile off, the Tyler’s gunners took aim on the

Arkansas, which returned fire from a pair of bow guns. Gwin had stopped the

Tyler’s engines, but he now called down to chief engineer Goble in the engine

room for full speed astern. “I then commenced backing down the river, hoping

that I would have speed enough to keep ahead of her and be able to fight most

of my battery,” Gwin explained, “but finding she was approaching me rapidly, I

rounded down the river and took a position about 100 yards distant on the port

bow of the Carondelet, which vessel was standing down.”

The Carondelet’s crew had also been piped to breakfast when

they heard the report of a gun. Morison recalled, “I looked through a port to

see what caused all the commotion and I beheld our gunboat and ram retreating

from a most formidable-looking monster which was coming down river in style, at

the same time keeping up a steady fire on the Tylor.” Walke barked at the gun

captain to fire a bow gun at the rebel ram, then paused to decide whether to

advance or retreat. If he fought the rebel ram bow on, he risked being

outmaneuvered; if he backed down, he exposed the gunboat’s vulnerable stern.

Walke turned to the helmsman and ordered him to go back down the river. The

Carondelet’s engines churned, and it sped down the Yazoo as fast as the stokers

could feed the boilers.

When the Tyler neared the Carondelet, Walke hailed Gwin and

ordered him to report the approach of the Arkansas to Davis. The Tyler’s

captain shook his head and kept the timberclad’s 30-pounder stern rifle

blasting away at the Arkansas. Occasionally, the Tyler’s broadside battery

joined in to support the embattled Carondelet.

For the next hour, the Arkansas pursued all three federal

vessels, pummeling them with fire from its bow guns. “I had got my gun cast

loose and ready as I could, which I did,” Morison wrote. “I now became very

warm, so I pulled my shirt and hat off, which made me feel better. The decks

were very slippery and I asked for sand, which was not to be had, but I soon

got a substitute in the shape of a flood of water which came pouring in through

a hole in the wheelhouse, caused by an eight-inch solid shot which came through

our stern, gutted the captain’s cabin, passed through the wheelhouse, steerage

and several steam pipes, and knocked a twelve inch oak log into splinters and

then rolled out on deck.” The Arkansas was close astern of the Carondelet now

and “steadily gaining on us,” the diarist noted. When Walke saw the ram headed

straight for the Carondelet, raking the gunboat with its 64-pounder guns, he

explained, “I avoided her prow, and as she came up we exchanged broadsides.” As

the ram swept by, the Carondelet’s bow gunners gave the rebel a few rounds. “I

got several good shots at her,” Morison claimed, “but I imagine without effect,

as her iron-cased sides did not look as if they were broached. She mounted ten

heavy guns, three on each side and two forward and aft. Altogether she was a

mighty unpleasant looking critter to be closing you up and at the same time

throwing solid shot through you.” As the Arkansas steamed past, Walke could see

two holes in its side and the crew frantically pumping and bailing.

“At last she touched our stern and then ranged up on our

starboard side,” gunner Morison wrote. “As she touched our stern, I fired the

last shot I could at her and came forward just as she poured her broadside guns

into us, which stove in our plating as if it were glass.” The ram then ran

across Carondelet’s bows, and Morison “fired a sixty-eight into her at less

than two yards distance, with what effect I don’t know. We then tried to bring

our port broadside to bear on her but she was not in range.” Fire from the

Arkansas had, however, cut the federal gunboat’s wheel ropes and destroyed

steam gauges and water pipes. “We had got aground, but after some work we got

afloat and followed her down as fast as our disabled condition would permit us.

I now had time to look around and I found that we had four killed, sixteen

wounded (some very severely) and twelve missing, all in one short hour’s

fight.” Many had leaped overboard to escape the steam and the enemy fire.

From the Tyler, acting master Coleman, signal officer for

the day, caught a final glimpse of the Carondelet up against the bank in a

cloud of enveloping smoke, “with steam escaping from her ports and . . . men jumping

overboard.” Coleman and Gwin both assumed the Arkansas would pause to take the

Pook turtle as a prize, but instead the ram pressed downstream. They all

remembered what had happened to the Mound City on the White River, when one

shot to the steam chest had inflicted so many casualties. “There was nothing

reassuring in the present situation,” Coleman noted, “for we were even more

vulnerable than the ‘Mound City,’ and it was evident that the ‘Tyler’ was no

match for an armored vessel such as was her antagonist.”

Gwin managed to keep a lead of 200 or 300 yards on the

Arkansas for a time, but then the ram began to gain on the Tyler, its bow guns

raking the timberclad’s stern. Gunner Herman Peters’s stern gun crew kept

firing on the rebel ironclad, but their shots merely bounced off the ram’s

sloping sides. Gwin remained grimly determined to outrun the Arkansas, but shot

and shell from his pursuer began to take a toll. A detachment of army

sharpshooters from the 4th Wisconsin Regiment bore the brunt of the enemy fire,

which killed the sharpshooters’ captain early in the engagement. Five soldiers

were also killed, and another five wounded. Then, as Gwin watched, a rebel shot

took pilot John Sebastian’s left arm clean off. He crumpled to the deck in a

pool of blood, but the second pilot, David Hiner, took the wheel. As several

crewmen carried Sebastian below to the surgeon, Gwin and Coleman realized that,

with the Carondelet now out of the fight, the only other federal vessel able to

fend off the rebel ram was the Queen of the West, which had been hanging back

several hundred yards astern of the Tyler. Gwin “called out to her commander to

move up, and ram the ‘Arkansas,’” Coleman wrote. “His only response to this was

to commence backing vigorously out of range, while Gwin was expressing his

opinion of him through the trumpet in that vigorous English a commander in

battle sometimes uses, when thing do not go altogether right.”

Although struck eleven times by enemy shot and shell and

pummeled by grape from the rebel ram, the Tyler continued moving downstream.

The timberclad’s stern gun crew blazed away at the rebel ram, but many of the

crewmen stood helplessly by their posts, unable to fight back. “Things looked

squally,” Coleman wrote. “Blood was flowing freely on board, and the crash of

timbers from time to time as the ‘Arkansas’ riddled us seemed to indicate that

some vital part would be soon struck. In fact our steering apparatus was shot

away, and we handled the vessel for some time soley with the engine[s] until

repairs could be made.” The killed and wounded, four of them headless, lay

everywhere on the Tyler’s deck, and the woodwork was spattered with blood and

shreds of flesh and hair. Few of the Tyler’s crewmen escaped without bloody

evidence on their clothing. A cut in the port safe pipe had enveloped the

timberclad’s after section in steam. “All knew that the vessel might go down

and all of us be killed, but there would be no surrender,” Coleman recalled.

Gwin “made that reassuring remark to the first lieutenant in my presence, when

the officer suggested such a possibility. We were fighting for existence and we

all knew it.”

Below, assistant surgeon Cadwallader and his men worked

feverishly to care for the men wounded by grape and shrapnel, many of them army

sharpshooters. So far, the Tyler had lost thirteen men killed, thirty-four

wounded, and ten missing in the fight with the Arkansas.

Early that morning, when the Tyler finally turned out into

the Mississippi River at Tuscumbia Bend, O’Neil recorded the moment the

Cincinnati sighted it. “At 5:15 heavy firing was heard up the Yazoo river which

increased and apparently drew near until 7:21 when the ‘Queen’ came out of the

Yazoo, followed immediately by the ‘Tyler,’ firing her stern guns and flying signal

‘I Have seen the Enemy.’”

When Gwin ducked out of the Tyler’s pilothouse to the

welcome sight of the federal fleet, he supposed “they would be in readiness to

give her [Arkansas] a warm reception,” Coleman recalled. “This was not the

case. The heavy firing had been heard of course but it was supposed that the

expedition was on its return and shelling the woods and no preparations were

made to meet the emergency.”

As the Tyler and Queen of the West came closer and the

gunfire grew louder, other officers in the fleet realized the Tyler’s dilemma,

and cries of “Clear for action!” and “Beat to quarters” rang out. Crews raced

to man their guns, and exasperated commanders swore and called down to their

engine rooms to raise steam. None of the commanding officers of Farragut’s

ships, Davis’s ironclads, or Ellet’s rams had anticipated the arrival of the

Arkansas. Most had only enough steam up to maintain their engines. The Arkansas

had caught them all napping. “Got steam up and slipped our cable immediately,

stood in towards the Mississippi shore,” O’Neil noted. “No other vessel in

either fleet, was yet underway with the exception of the ‘Tyler’ & ‘Queen

of the West.’ Farragut made signal to two of his vessels the ‘Oneida’ &

‘Winona’ to get underway when the ‘Tyler’ first made her appearance but

unfortunately he [came] upon the only two of his boats that had no steam.”

The rebel ram also surprised the men of Lieutenant Kidder

Breese’s five mortar vessels, anchored just out of gunshot range on the right

bank of the river. Although Breese had heard gunfire up the river, he did not

raise the alarm until an officer came to the bank and hailed him. “[He] stated

that the rebel ram Arkansas was attempting to run through the fleet, and she

would probably succeed.” Breese immediately passed the word to the division to

heave short.

Swept along by the Mississippi’s current, the Arkansas

approached the federal fleet. Vicksburg was still a ways off, but Brown’s eyes

rested on the enemy in every direction. “It seemed at a glance as if the whole

navy has come to keep me away from that heroic city.” Observing federal rams

and ironclads poised to oppose the Arkansas, Brown told the pilot, “Brady,

shave that line of men-of-war as close as you can, so that the rams will not have

room to gather head-way in coming out to strike us.”

As the Arkansas rounded the point at about 8:00, the mortar

flotilla’s Second Division commander, William B. Renshaw, signaled the mortar

schooners to get under way. They all dropped down close to the bank, except for

the Sidney C. Jones, which was aground and had been left in a defenseless

position. The Jones’s commander, acting master Charles Jack, signaled Renshaw,

“Shall I destroy her?” Renshaw told Jack to “get ready” to blow up the Jones, but

not until he received orders to do so “or the ram was actually coming down upon

him.” Renshaw then went to see Bell, who reported that Farragut had directed

him to bring the mortars to bear on the rebel batteries. Meanwhile, the Jones’s

crew spiked the mortar and two 32-pounder guns and detonated the explosives,

blowing the schooner up in a shower of fragments. It burned to the water’s

edge. Despite a hail of enemy fire from guns and sharpshooters on the opposite

bank, the schooners John Griffith, Oliver H. Lee, and Henry Jones managed to

open fire with their mortars on the rebel batteries.

Hoping to reach the shelter of the rebel batteries on the

bluffs, the captain of the Arkansas had decided to steam rapidly through the

Yankee fleet. “The ‘Arkansas,’ as the Rebel Ram proved to be, held her course

steadily along the Louisiana shore,” O’Neil explained, “between the fleet &

the transports along the banks, firing briskly in all directions, but with

apparently little effect except in one or two instances.” In the first

instance, the Arkansas “got a shot into the Boilers of the ram ‘Lancaster’

killing or wounding many by escaping steam.”