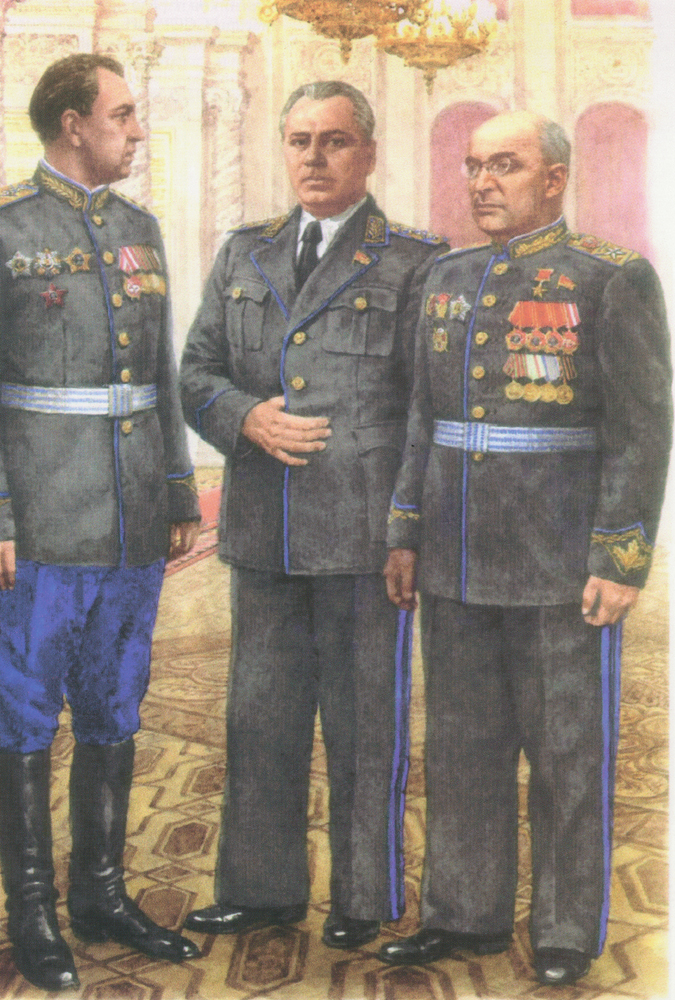

From left to right: military counterintelligence chief (SMERSH) Viktor Abakumov, NKGB Commissar Vsevolod Merkulov, and NKVD Commissar Lavrenty Beria.

During WWII the NKVD continued propaganda and coercion, which as before, went hand in hand. This leopard did not change its spots; terror did not abate during the war. Those who had lived under German occupation, or who had become prisoners of war and escaped, suffered the consequences of NKVD suspicion, and hundreds of thousands of them were arrested. The Soviet regime punished the families of deserters. A new phenomenon during the war was the punishment of entire nations: the Volga Germans were deported immediately at the outbreak of the war. In 1943 and 1944 it was the turn of the Crimean Tatars and Muslim minorities of the Caucasus: deported to Central Asia, they lived in the most inhuman conditions. The new element in this terror was its naked racism. Every member belonging to a certain minority group was punished, regardless of class status, past behavior, or achievements. Communist party secretaries were deported as well as artists, peasants, and workers.

Despite the arrests, the number of prisoners in camps

declined during the war. This happened partly because inmates were sent to the

front in punishment battalions, where they fought in the most dangerous

sections. The morale and heroism of these battalions were impressive: most of

the soldiers did not survive. The camps were also depopulated by the

extraordinary death rates: approximately a quarter of the inmates died every

year. People died because of mistreatment, overwork, and undernourishment.

In wartime nothing is more important than maintaining the

morale and loyalty of the armed forces. In addressing this need the Soviet

Union learned from decades of experience. At first, the regime reverted to the

dual command system it had developed during a previous time of crisis, the

civil war. From the regimental level up, political appointees supervised

regular officers. They were responsible for the loyalty of the officers and at

the same time directed the political education system. The abandonment of

united command, however, harmed military efficiency; once the most dangerous

first year had passed, the Stalinist leadership reestablished united command.

This did not mean that the political officers had no further role to play. The

network of commissars, supervised by the chief political administration of the

army, survived. The commissars carried out propaganda among the troops: they

organized lectures, discussed the daily press with the soldiers, and

participated in organizing agitational trains that brought films and theater

productions to the front.

Yet another network within the army functioned to assure the

loyalty of the troops – the network of security officers. Although these men

wore military uniforms, they were entirely independent of the high command and

reported directly to the NKVD. According to contemporary reports, these

security officers were greatly disliked by regular officers.

The principal Soviet foreign intelligence service, the

Narodnyi Komissariat Vnutrennykh Del was headed in Moscow by Lavrenti Beria and

operated across the globe through legal and illegal rezidenturas, run by the

head of foreign intelligence, Pavel Fitin, which were heavily dependent on

local Communist parties for support and sources. Considered the sword and the

shield of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the NKVD concentrated on the

acquisition of technology and industrial processes before the war, but later

concentrated on political intelligence and atomic data.

NKVD rezidenturas were usually concealed in either diplomatic

or trade missions headed by a resident, who supervised a team of subordinates

that managed networks of agents, either directly or through intermediaries.

Their operations were directed in detail from Moscow, as was learned

subsequently from the study of the relevant VENONA traffic, which revealed

aspects of NKVD wartime agent management in Mexico City, Washington, D.C., San

Francisco, New York, London, and Stockholm. Evidently the NKVD’s ability to

function in western Europe following the Nazi repudiation of the

Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact in June 1941 was severely handicapped, leaving the

Soviets devoid of legal rezidenturas in Berlin, Copenhagen, Paris, The Hague,

Oslo, Rome, Prague, Bern, Belgrade, Bucharest, Budapest, Warsaw, Helsinki,

Tallinn, Riga, Vilnius, and possibly Madrid and Lisbon, too. This placed a

heavy burden on the rezidenturas in London, Ottawa, Mexico City, Stockholm, the

three in the United States, and eventually Buenos Aires when a rezident was

posted there in 1944.

In London, the NKVD declared a rezident, Ivan Chichayev, to

his hosts for liaison purposes, but in reality continued to conduct local

intelligence-gathering operations through numerous agents, among them Guy

Burgess, Kim Philby, Leo Long, and Anthony Blunt, who penetrated various

branches of British intelligence under the direction of the undeclared

rezident, Anatoli Gorsky. In addition, Melita Norwood, Klaus Fuchs, and Allan

Nunn May passed information to the NKVD from inside the British atomic weapons

development program.

In Ottawa, the NKVD rezident, Vitali Pavlov, ran few

independent operations, because the local Communist Party had been embraced by

his GRU counterpart, Nikolai Zabotin. In Mexico, Lev Vasilevsky ran the embassy

rezidentura under the alias Lev Tarasov and was largely dependent on Spanish

Republican refugees. In Stockholm, the rezidentura was headed by a Mrs.

Yartseva and then Vasili Razin, and it concentrated on the development of local

political figures.

Gorsky (code-named VADIM, alias Anatoli Gromov) was

appointed rezident in Washington, D.C., in September 1944, a post he held until

December the following year, when he was transferred to Buenos Aires. In March

1945, the New York rezident, Stepan Apresyan, was posted to San Francisco, a

rezidentura that had been opened in December 1941 by Grigori M. Kheifets

(code-named CHARON), with a subrezidentura in Los Angeles. Kheifets was

recalled to Moscow in January 1945 and replaced by Grigori P. Kasparov

(code-named GIFT). Apresyan’s replacement in New York was Pavel Fedosimov

(code-named STEPAN). Together, these NKVD officers ran more than 200 spies, of

whom 115 were later identified as U.S. citizens with a further 100 undetected.

On the Eastern Front, the NKVD gained a ruthless reputation

for capturing enemy agents and managing entire networks of double agents, often

at the expense of having to sacrifice authentic information to enhance the

standing of their deception campaigns. In the 18 months up to September 1943,

the NKVD turned 80 captured enemy agents equipped with wireless transmitters,

and by the end of hostilities, it had run 185 double agents with radios.

NKVD Security Forces

NKVD Security Forces Aside from combat units of the Red Army, Soviet state security forces fielded a large number of combat units during the war. In 1941 the NKVD was responsible for the Border Troops who patrolled along the frontier, and these look a very active part in the initial fighting of June 1941. The war also saw a major expansion in the NKVD Internal Troops. These units were organised like rifle or cavalry divisions and were intended to maintain internal order in the Soviet Union. At the beginning of the war the NKVD formed 15 rifle divisions. At times of crisis, these units were committed to the front like regular rifle divisions. Indeed, the NKVD formed some of them into Special Purpose (Spetsnaz) Armies, and one of these was used during the breakthroughs in the Crimea. However, this was not their primary role. They were intended to stiffen the resistance of the Red Army, and during major operations were often formed into ‘blocking detachments’ which collected stragglers and prevented retreats. Their other role was to hunt out anti-Soviet partisan groups, and to carry out punitive expeditions against ethnic groups suspected of collaborating with the Germans. The NKVD special troops were expanded in the final years of the war, eventually totalling 53 divisions and 28 brigades, not counting the Border Troops. This was equal to about a tenth of the total number of regular Red Army rifle divisions. These units were used in the prolonged partisan wars in the Ukraine and the Baltic republics which lasted until the early 1950s. They were also involved in the wholesale deportations of suspected ethnic groups in 1943-45. In some respects, the NKVD formations resembled the German Waffen-SS in terms of independence from the normal military structure. However, the NKVD troops were used mainly for internal security and repression, and were not heavily enough armed for front-line combat. Unlike the Waffen-SS, they had no major armoured or mechanised formations.