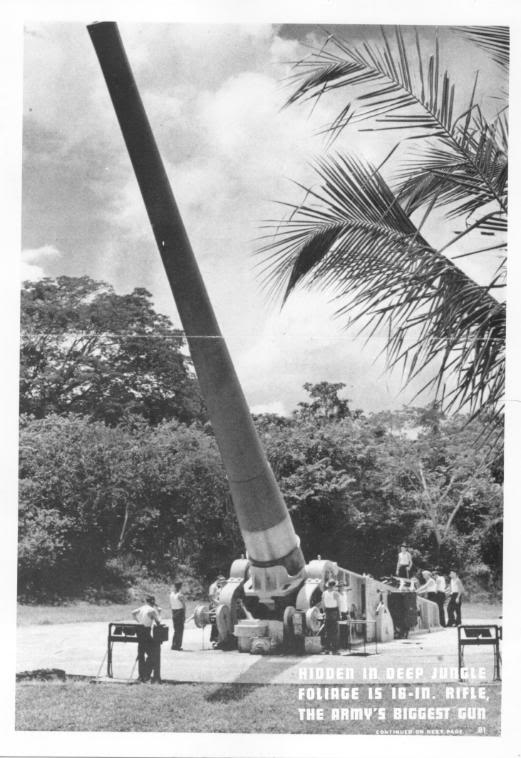

16-inch Navy Mk.II M1 gun on M1919 barbette mount in Panama.

Fortifying the Canal

The Hay-Pauceforte and Hay-Bunau-Varilla

treaties implied but did not specifically give the United States the right to

fortify the Canal Zone. Central to America’s decision to fortify was Article Three

of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty, which gave the United States all powers,

rights, and authority in the Zone. Panama protested in 1904 when the United

States government used this sovereignty in establishing ports of entry,

customhouses, tariffs, and post offices in the Zone. An amendment giving some

concessions to Panama in those areas was made after Secretary of War Taft,

George Goethals, and other Army leaders visited the Isthmus in November 1904 to

determine questions relating to possible fortifications. The amendment was

supposed to be in effect only during the construction period, but it lasted

until 1924, and efforts for a new treaty were unsuccessful.

The debate over Canal fortification

continued until 1911, when Congress passed a $2 million appropriation for that

purpose. The following year, Congress added $1 million for gun and mortar

batteries and $200,000 for land defenses. Construction began on 7 August 1911

under Sydney Williamson, Goethals’ Chief of the Pacific Division, and on 1

January 1912, Goethals’ son, Lieutenant George R. Goethals, was put in charge

of fortification work. The construction towns of Empire and Culebra, no longer

needed, were used for the Army garrisons. There were large forts with gun

batteries built at each end of the Canal, with field work for 6,000 mobile

force troops (infantry, cavalry, engineer, signal, and field artillery). The

work of The Panama Canal staff increased significantly with the 1915 military

appropriation of $1,290,000 and subsequent assignment of Army barracks and

quarters construction. All design and construction work for Army post buildings

was assigned to The Panama Canal. Much of the early quarters construction

undertaken by The Panama Canal for the Army utilized existing “type

house” designs. By June 1915, almost $15 million had been spent on

fortifying the Canal, including the locks and dams. Military reservations were

officially designated on 18 September 1917 as Fort Grant, Fort Amador, Fort

Sherman, Fort Randolph, and Fort de Lesseps.19 That same year The Panama Canal

designers were asked “… to furnish preliminary plans and estimates for

cantonment construction for Army troops and for the proposed permanent posts

for mobile troops on the Canal Zone.”20

This request developed from the investigation

and findings of an Army Board of Officers convened to recommend post locations

for the troops in the Canal Zone, and to recommend the type and character of

buildings required. The Board members represented the Infantry, Engineer Corps,

Cavalry, Medical Corps, and Field Artillery. In their report, dated 28 August

1917, the Board recommended placing one brigade of infantry at Gatun, and all

other mobile force troops on the Pacific side. There, they supported the

location of one infantry brigade at Miraflores Dump, another adjacent to the

Curundu River, and one artillery brigade and one cavalry regiment south of the

Diablo Ridge. Corozal was the location recommended for the sanitary troops, the

Signal Corps troops, and the Engineer regiment, as well as for the main supply

depot site. Quarry Heights (created on the site of the former Ancon Quarry)

would serve as department and division headquarters.21

The placement of troops on the Isthmus did

not wait for the construction of military reservations. As early as 1903, there

was a Marine detachment present that kept the Panama Railroad open during the

revolution. This detachment remained until January 1914, and at the end

consisted of 12 officers and 375 enlisted men. The first permanent Army troops

(Tenth Infantry) arrived in October 1911 and were stationed at Camp E. S. Otis

in Empire. Three companies of the Coast Artillery Corps arrived on the Isthmus

September 1914 and were in temporary quarters at Fort Amador and Fort Sherman

by November. That same month the Fifth Infantry arrived with several members of

the Medical Corps and the Quartermaster Corps, and the regiment was quartered

at Empire. Continued arrivals placed the troop strength on the Canal Zone at

approximately 5,000 when the United States entered World War I. 22 Authority

over the Panama Canal and the Canal Zone was transferred from the Canal Zone

Governor to the commanding general of the U.S. Army forces in the Canal Zone by

President Woodrow Wilson in a 9 April 1917 Executive Order.23 An additional

Executive Order was used to proclaim the neutrality of the Canal on 23 May

1917.24

A consolidated command called United States

Troops, Panama Canal Zone had been put into place on 6 January 1915 under Brig.

Gen. C. R. Edwards, as part of the Eastern Department. Initially located at

Ancon, the headquarters were moved to Quarry Heights in 1916. A separate

geographical department was created 1 July 1917 and named the Panama Canal

Department of the United States Army. Also headquartered at Quarry Heights, the

Department was first commanded by Brigadier General Cronkhite25. The war passed

quietly enough in the Canal Zone, and control of the Canal was returned to the

Governor at the war’s end.

For the Panama Canal Department, the

inter-war years provided an opportunity to increase defensive strength by

creating permanent posts and upgrading defenses against the growing threat of

air attack.

When Canal defense requirements were first

considered, the threat to be countered was primarily a naval one. Armament and

fortifications were planned to repel a frontal naval assault and landing. As

aviation technology developed, aerial attacks were perceived as a growing

threat, and steps were taken to counteract them. The Army Air Force in the

Canal Zone was implemented to “gain and maintain sufficient air

superiority to secure the Canal and its accessories against an air attack, to

observe fire for the Coast and Field Artillery, to cooperate with the Infantry,

to attack any enemy land or naval forces and to cooperate with the Navy in the

execution of its mission.”26 By late 1920, the Army aviation base of

France Field, and the infantry bases of Fort Clayton (Pacific) and Fort Davis

(Atlantic) were in place and manned. By 1925 the Coast Artillery District was

abolished and Coast Defense units organized into regiments with separate

antiaircraft batteries. A Pacific-side air field (Albrook Field) was

constructed by 1932.27

In 1932, the Panama Canal Department was

divided into Atlantic and Pacific sectors. The Atlantic Sector contained France

Field and the Panama Air Depot, and Forts Sherman, Randolph, Davis, and de

Lesseps, while Forts Amador, Clayton, and Kobbe, Albrook Field, and the Post of

Corozal were located in the Pacific Sector.28 Headquarters remained at Quarry

Heights. In January 1934, the Department consisted of 419 officers and 8,884

enlisted men. This manpower level was considered too low, and by 1936 enlisted

strength had increased to 12,990.29

Diplomatic issues continued to be

negotiated between Panama and the United States. The Hull-Alfaro Treaty, signed

on 2 March 1936, helped settle differences over the devaluing Panama dollar and

the Canal annuity payments. It guaranteed joint action and consultation between

the countries in times of emergency. The United States also gave up the right

to intervene in Panama to maintain public order. After debate in the United

States over whether the treaty adequately protected American interests in the

area, the Senate ratified it three years later.30

As World War II broke out in Europe,

efforts were underway in the Canal Zone to heighten defenses. One of these

efforts had both defensive and economic justifications. The original Canal

designers were aware that transit capacity would need to be increased in the

future, both in terms of ship size and the number of ships able to transit at

any one time. After several years of military and civilian study, Congress

authorized the construction of an additional set of locks in 1939. Known as the

“third locks project,” new, larger locks would be constructed near

the existing ones at Gatun, Pedro Miguel, and Miraflores to increase capacity.

For defense purposes, they would be built some distance away (1,500 to 3,000

ft) and connected to the existing locks by approach channels. An initial appropriation

of $15 million was made through the War Department Civil Appropriations Act of

1941. The total cost of the expansion was estimated at $277,000,000. A Special

Engineering Division of the Department of Operation and Maintenance was created

to handle the work in close cooperation with existing Panama Canal

organizations. Canal employees had been producing plans for the design and

construction and selecting potential key employees in the United States since

the 1939 authorization. Among the first orders of business were three new

construction towns (Caecal, Diablo Heights, and Margarita) for the estimated

6,300 employees and dependents associated with the project.31

Excavation at the Pacific end of what would

be the approach channel to the new Miraflores lock was begun on 1 July 1940.

The new locks were designed to be used by the 58,000 ton Montana class

battleships on order for the Navy. As the threat of war heated up, defense

considerations soon outweighed those of commerce. However, upon the United

States’ entry into the war, continuation of the project grew uncertain. There

was strong Navy support for completing the project as soon as possible to

accommodate the warships due in late 1945. Through a series of meetings held in

January 1942, the War Department decided to accept the Navy position and to

press for rapid completion. Some military officers, however, felt the extra

locks only provided another target for air attack. Several months later

circumstances changed when the Navy indefinitely postponed its battleship

construction program. As a result of these factors, the War Department, the

Navy, and the President all concurred in a decision to halt almost all work on

the third locks, effectively canceling the project.32

As World War II approached, Canal Zone Army

installations were reinforced by increasing the troop strength in Panama from

13,451 in 1939 to 31,400 by the time of the United States’ entry in December

1941. Garrison strength was up to 66,619 by January 1943. Housing these reinforcements

constituted only part of a larger construction program. As some troops arrived

before construction had begun, however, housing was given the highest priority.

Congress appropriated $50 million on 10 June 1939 for improvement of Panama

Canal defenses.33

Subsequent contract discussions delayed

calls for bids until March 1940. The first contractors arrived on the Isthmus

in July 1940. Troop labor was used in the meantime to clear construction sites

and put in footings. Housing needs were especially acute, and a Board of

Officers was appointed to study and report on “the locations and general

layout, plan for the new construction in the Pacific Sector contemplated in the

Panama Canal Department housing program, the Coast Artillery Expansion Program,

and the Air Corps Augmentation Program.34 Once begun, actual construction was

fairly swift, as it was essential to get men and materiel out of tents and into

buildings as quickly as possible. Even so, it was a huge job and every

available soldier was detailed to some aspect of construction. Little civilian

labor was available to assist with the military construction, as the Third

Locks project competed for workers.35 Due to the severe time constraints, much

of the new construction was of a temporary nature. It was common to use

existing building plans but substitute readily available, less expensive, and

less labor-intensive construction materials. Designs were stripped down to the

essentials, and all ornamental details were eliminated. Temporary structures

were less durable, and many were intended to be easily disassembled and

reerected elsewhere.

Emergency measures were initiated in the

last days of August 1939, and in addition to troop buildup, included

anti-sabotage measures and a change of Canal authority. The Army garrison was

given the mission of “protecting the Canal against sabotage and of

defending it from positions within the Canal Zone.”36 The Navy was tasked

to provide offshore defense, provide armed guards for ships transiting the Canal,

and maintain a harbor patrol at both ends of the Canal.37 As early as 5

September 1939, an Executive Order was issued transferring jurisdiction and

authority over the Canal and the Canal Zone to the Army’s Panama Canal

Department.38 Before long, photography of Canal installations was banned for

the duration of the war, mines were placed at both entrances to the Canal,

low-altitude barrage balloons were placed over the locks with anti-submarine

and torpedo nets placed in front of the locks, and chemical smoke pots were

positioned throughout a 60 square mile area. The massive guns and batteries on

military installations at either end of the Canal were prepared for use. The 6

to 16 inch (in.) guns were housed in 11 Atlantic and 12 Pacific batteries, and

had a range up to 25 miles. To protect against air attack, anti-aircraft

batteries were put in place across the Zone and two antiaircraft detachments

were sent in September 1939. Two long-range radar stations were also

established that autumn. The main runway at Albrook Field was improved to allow

deployment of the more modem bombers that had arrived in June 1939. Military

dependents were evacuated to the United States by October 1941.39

Also around 1939, the Panama Canal

Department commander began an effort to secure additional defense sites outside

the Canal Zone in the Republic of Panama, primarily for airfields. Dozens of

sites were eventually requested, but action on this request ran into diplomatic

trouble between the United States and Panama. The primary problems were leasing

versus buying the sites, and the limits of United States defense authority as

defined in the as yet unratified 1936 Hull-Alfaro Treaty. The Treaty was

finally ratified on 17 April 1939, and negotiations continued for the

additional defense sites even as funding was allocated to lease them from the

Panamanian government. An agreement was reached on 21 March 1941 to allow

United States forces to acquire sites and begin use before formal approval. On

18 May 1942, the two countries signed the Defense Sites Agreement, in which the

United States would utilize 134 sites leased from Panama until one year after

the end of the war.40

By the time the build-up was complete,

defenses consisted of “nine airbases and airdromes, 10 ground forces posts,

30 aircraft warning stations, and 634 searchlights, antiaircraft gun positions

and miscellaneous tactical and logistical installations.”41 Twelve

outlying airbases were also constructed in Peru, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua,

and Costa Rica. An outer defense parameter of 960 nautical miles from the Canal

was established and patrolled by air and sea.42

In 1941, a major command reorganization was

precipitated when the United States took into protective custody the British

possessions (and prospective base sites) of Jamaica, Antigua, St. Lucia,

Trinidad, and British Guyana. To administer these new bases, and to quell

issues of command extent between the various Army and Navy forces in the area,

a theater command was established. The Caribbean Defense Command was officially

activated on 10 February 1941, under the command of General Daniel Van Voorhis,

then the commander of the Panama Canal Department. The Caribbean Defense

Command was initially set up as strictly Army, and coordination with Navy

operations was by “mutual cooperations” A separate command, the

Caribbean Air Force, was established for air defense about the same time.

General Frank M. Andrews succeeded General Van Voorhis in August 194l.43

The Army and Navy personnel in Panama had

been on full alert since midsummer 1941. The first immediate effects of the

United States’ December entry into the war were ones of command structure and

reinforcements. The first order of business was to create a unified command

through which Army and Navy could be coordinated. President Roosevelt put the

Army in charge of the Panama sector, and the Navy in charge of the more distant

Caribbean Coastal Frontier on 12 December 1941. General Andrews thus assumed

command of both Army and Navy forces in the area on 18 December 1941.44 Both

air and ground forces were heavily augmented over the next two months, with the

Panama garrison strength reaching 39,000 by the end of December, and growing to

47,600 by the end of January 1942.45

For those living and working in the Canal Zone,

World War II was “a time of perceived danger during which the movement of

materiel, troops and supplies through the waterway was a critical part of the

war effort.”46 While Panama and the Canal both escaped enemy attack, a

damaging U-boat campaign was carried out against shipping in the Caribbean.

From February through December 1942, some 270 ships in the area had been sunk

by U-boats. The peak of the German U-boat threat came in the summer of 1942. In

the month of June alone, 29 vessels were sunk in the Atlantic Sector of the

Panama Sea Frontier.47 Caribbean Defense Command peak strength of 119,000 was

reached in December 1942. Of these, over half were stationed in Panama to

protect the Canal from attack or sabotage.48 by mid-summer 1943, the U-boat threat

was receding due to increased effectiveness of the theater’s antisubmarine

forces, the effects of Allied victories in other waters, and the shift of

U-boats away from the Caribbean.49

With the threat of Canal attack

diminishing, the reduction of troop strength became feasible. Downsizing was

begun in January 1943, and continued until the end of the war. From a peak of

119,000, Army forces had dropped to 91,000 by the end of 1943. When the war in

Europe ended in May 1945, Caribbean Defense Command strength was down to

67,500.50 War-time defenses, including large artillery guns, landing fields,

and mine fields were removed as the military returned to a peace-time defensive

position. The Caribbean Defense Command was reorganized into the U.S. Army Caribbean

and the Caribbean Command (a unified authority over the Army, Navy, and Air

Force components)51 This command structure would last until 1963, was

redesignated as the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), and the Army

component became the United States Army Forces Southern Command (USAFSO). The

major Army command would be inactivated in 1974, then re-activated as the

United States Army South (USARSO) in 1986.52

In October 1947, the United States tried to

negotiate an agreement for five more years occupation of 13 auxiliary World War

II sites and the military air base at Rio Hato, 70 miles west of Panama City,

for 10 to 20 years. In December, with pressure from the Communist Party in

Panama and student anti-American demonstrations, the Panamanian Assembly

unanimously rejected the agreement, and the United States agreed to evacuate

the remaining 14 sites immediately, while continuing to negotiate. With

national elections coming up in 1948, Assembly members wanted to reduce

American influence in Panama as much as possible to appease the voters.53

In the 1950s, the United States made

several concessions to the Panamanians: a single pay scale for American and

Panamanian workers was established; Spanish became an official language in the

Canal Zone along with English; Panama was given more money from Canal toll

collections. The United States was given 19,000 acres in the Rio Hato area for

military training. Panama, however, twice rejected requests by the U.S. to

deploy Nike missiles in 1956 and 1958. Two ground-to-air HAWK-AW missile

batteries were deployed in 1960 at Fort Sherman and Fort Amador. Growing

nationalistic sentiment expressed in student demonstrations in 1955, 1958,

1959, and 1964 helped to finally convince the United States to renegotiate the

Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty.54

In 1974, the United States, under chief

negotiator Ellsworth Bunker, agreed in principle to relinquish control of the

Panama Canal and the Canal Zone to Panama. At that time, there were about

46,000 people living in the Canal Zone. Most (30,000) were active duty

military, their dependents, and civilian employees. Roughly 10,000 Americans

(employees and dependents) were associated with the Panama Canal Company.

During the administrations of President Jimmy Carter and General Omar Torrijos,

two treaties were negotiated. The first, called the Panama Canal Treaty,

abolished the Canal Zone and returned the territory to Panama, with the United

States having the authority to manage, operate and defend the Canal with

increasing participation by the Republic of Panama. At noon on 31 December

1999, Panama will assume control of the area and responsibility for the Canal

as the United States’ presence ends. The second treaty gave the United States

the permanent right to defend, jointly with the Republic of Panama, the Canal’s

neutrality. The treaties were signed on 7 September 1977 by Presidents Carter

and Torrijos at the Organization of American States. After months of heated

debate, the United States Senate passed the two treaties in March and April

1978, each by a vote of 68 to 32, drastically changing American military and

political influence in Panama.55

Implemented on 1 October 1979, the Panama

Canal Treaty impacted U.S. armed forces in Panama through the immediate

turnover of some military facilities, the relocation of other facilities, and

the undertaking of some social responsibilities formerly run by the Panama

Canal Company. Some facilities at Fort Amador were turned over to the

Panamanian government immediately, necessitating the relocation of U.S. Army

headquarters to Fort Clayton. Facilities were also shifted from the Albrook

Army Airfield to Air Force installations in the former Canal Zone. The

Department of Defense became responsible for the education, health care, and

postal services previously run by the Panama Canal Company. Since 1979, the

turnover of military facilities has continued and will proceed until the

expiration of the Panama Canal Treaty at 12 noon on 31 December 1999.56

U.S. Military Aviation in Panama

World War I and France Field

The outbreak of World War I brought the

first pioneering aviation operations to the Canal Zone. As the efficiency of

combat aviation progressed during that conflict, it became clear that the U.S.

must provide some form of air force for the defense of the Canal. In March

1917, just prior to American entry into the War, the 7th Aero Squadron deployed

to Panama to provide aerial reconnaissance capabilities in cooperation with

Navy and Coast Artillery forces in the Canal Zone. This first aviation unit

consisted of just two officer pilots and 51 enlisted men, under the command of

Captain H. H. “Hap” Arnold. Its entire aircraft complement consisted

of two Curtiss R-4 observation planes. For the first few months after arrival

in Panama, the 7th shifted its operations between a number of Army bases while

its new flying field was under development. March found the 7th at Corozal, but

it immediately moved to Camp Empire, and then to Fort Sherman by August 1917.

In the meantime, development had begun on a new Army air field adjacent to the

Navy’s air station at Coco Solo. The first preliminary improvements centered

around providing an adequate landing surface, which was accomplished by laying

a base of crushed coral and covering it with hydraulic fill. Grass was planted

over this base by August 1918, at which time flying operations commenced on a

small scale. It was not until January 1919, however, that the 7th permanently

moved into its new quarters at France Field. After the war, a significant construction

program commenced in order to provide permanent facilities for the Air Corps’

growing commitment in Panama. Most of the original permanent construction at

France Field was completed between 1920 and 1922, including a new flight line

with six hangars. Nevertheless, significant problems plagued France Field

throughout its existence, centering around its inferior landing surface. Its

flying field could not be expanded due to its location. More importantly, the

coral foundation was prone to constant uneven settling, which required an

inordinate amount of costly new filling and leveling work. It was also rather

brittle and could not safely support the ever-increasing weights of new

aircraft. Already by the early 1930s, France Field was deemed unsafe for the

operation of the large bombers and commercial aircraft of the day. As soon as

other airfields were available in the Canal Zone, it became a secondary

operation. Eventually, the limitations of its landing surface prohibited France

Field’s efficient use as an Air Force Base. By late 1949, France Air Force Base

supported only a small caretaker detachment. In accordance with Canal Zone

Order Number 54, it ceased to be an Air Force. installation on 22 August 1960,

and its lands were assigned to the Department of the Army, Department of the

Navy, and The Panama Canal Company.57