432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, Udorn RTAFB, Thailand.

13th TFS equipped with F-4Ds in Oct 1967. Redesignated 432nd Tactical Fighter

Wing Nov 1974.

The squadron traces its heritage back to the 1942

activation of the 313th Bombardment Squadron. The squadron served in the

continental United States as a training unit until its 1943 inactivation. The

squadron was reactivated in 1966 as the 13th Tactical Fighter Squadron,

fighting in the Vietnam War. The squadron flew Wild Weasel anti-SAM missions

with the Republic F-105 Thunderchief and McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II,

operating out of Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base. The squadron moved to Udorn

Royal Thai Air Force Base in October 1967, flying F-4s in combat air patrols

against North Vietnamese MiGs and ground strike missions. The squadron was

inactivated with the end of the war in 1975. The squadron was reactivated in

1976 a training squadron at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, and inactivated

again in 1982. The squadron was reactivated as the 13th Tactical Fighter

Squadron in 1985 at Misawa, flying the F-16. It was redesignated the 13th

Fighter Squadron in 1991.

All four October 1967 MiG kills were assisted by the more

effective use of the QRC-248 IFF transponder interrogator that had been

installed in College Eye EC-121Ds from May of that same year onwards. This

device could read the SRO-2 IFF transponder installed in VPAF MiGs, enabling

EC-121D crews to tell which of the radar blips over the North were hostile,

particularly at low altitudes. North Vietnamese GCI relied on the SRO-2 when

directing their fighters towards strike packages.

Initially, College Eye operators were forbidden to

interrogate the transponders actively in case the QRC-248’s capability was

accidentally revealed, so they had to wait for ground-based North Vietnamese

GCI controllers to do this for them and then calculate the MiGs’ positions

passively. Nevertheless, the device was still extremely valuable for it

revealed the MiGs’ mission procedures and gave valid, specific MiG warnings to

US aircraft over the North.

From 6 October the improved Rivet Top and College Eye EC-121

crews were allowed to interrogate actively, giving strike force crews much

better information about the location of MiG threats so that they could be

positioned to meet high-speed interceptions under far more favourable

conditions. Despite this, the MiG-21 force achieved a 3-to-2 success ratio

during October, and maintained this advantage throughout November thanks to the

grounding of the EC-121 Rivet Tops for vital modification work.

By then some MiG-21 pilots had already sensed that they were

being monitored, and they would routinely switch off their transponders. Little

intelligence pertaining to this new technology was imparted to the F-4 units,

however, as Don Logeman explained;

`Most aircrew at Ubon had at least a nodding acquaintance

with the Rivet Top capabilities, but the in-depth understanding and

tactical/strategic significance and application of it was all pretty much the

property of the senior leaders and weapons/tactics guys.’

Logeman recalled another factor that assisted their 26

October duel;

`Our adversary MiG-17s came up to engage us well above

their optimum manoeuvring altitude. We were taught that, whenever possible, we

should engage the MiG-17 at as high an altitude as you could get him and the

MiG-21 as low as you could get him in order to capitalise on their manoeuvring

disadvantages relative to the F-4 in those operating regimes. The best turn

rate (corner velocity) in the F-4 was about 380 knots.’

On 17 December the much-maligned AIM-4 achieved its second

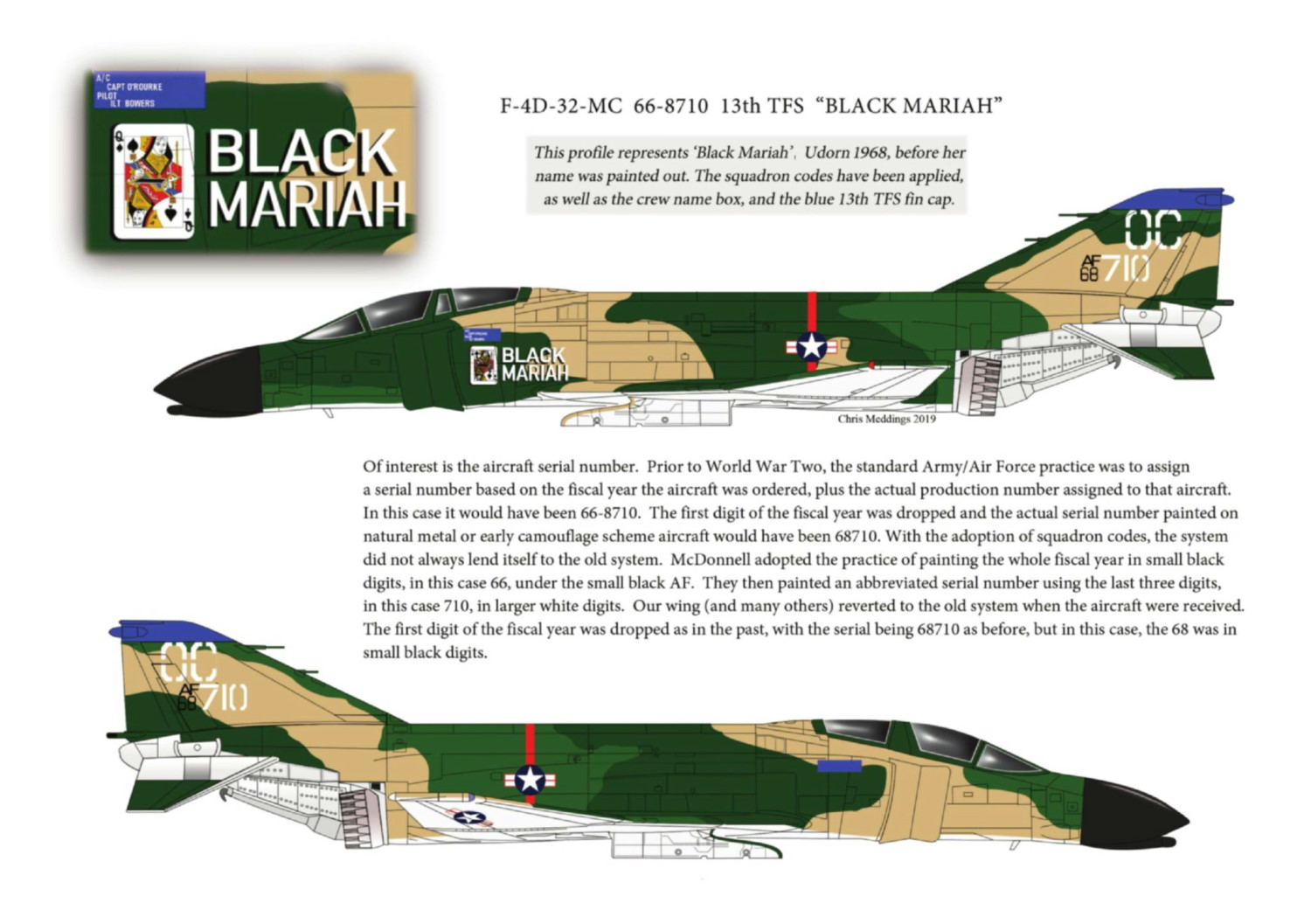

kill, this victory being the first for the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing (TRW).

The latter had broadened its capabilities with the arrival of the F-4D-equipped

13th TFS at Udorn in October 1967. Uniquely, the wing’s opening victory fell to

US Marine Corps exchange officer Capt Doyle Baker (who had flown F-4Bs

in-country with VMFA-513 in 1965) and `GIB’ 1Lt John D Ryan.

Their F-4D (66-8719) was `Gambit 03′ in a MiGCAP flight

escorting a substantial F-105/F-4 attack on three Route Package VI targets. In

a break from routine procedure, the mission leader had declared prior to

take-off that any flight member who spotted a MiG would be allowed by his

flight lead to attack it.

Baker saw a low-flying, Gia Lam-based MiG-17 approaching

from below, and he turned through 270 degrees before making a diving attack on

it. Initially firing short bursts from his SUU-23/A gun pod, he then climbed

back up to 10,000 ft in order to reposition himself for a second crack at the

MiG. Baker made three more gun passes at it without success before eventually

running out of 20 mm shells.

The VPAF pilot levelled out at 2000 ft and seemed to be

making a dash for home. Baker set up an AIM-4 launch from two miles astern in a

ten-degree dive. His description of what happened next is as follows;

`I ignited the afterburners and rolled the aeroplane,

increasing speed to keep the MiG in sight. The forces of acceleration were so

great that I could hardly see anything. Finally, at 500 ft and 600 knots I

fired. The Falcon worked perfectly, going directly up the MiG-17’s tailpipe and

exploding.’

In that engagement the VPAF fighter force had overwhelmed a

two- pronged US attack with up to 20 MiGs. The MiG-17s had timed their attacks

on the MiGCAP F-4s to coincide with a series of thrusts made by MiG-21s against

the bombers, resulting in the loss of both a 388th TFW F-105D and an 8th TFW

F-4D (66-7774, piloted by Maj Kenneth Fleenor, who was one of the first USAF

pilots to convert onto the F-4).

The remaining three AIM-4 successes came in the early weeks

of 1968, and the first was scored by a `Wolfpack’ crew on 3 January. A

considerable F-4D/F-105 strike force was targeted on railyards and bridges in

the Hanoi area, and despite some MiG-21 action on the way in, there were no

losses. MiG-17s then harassed the strike elements of `Bravo’ force as they

egressed, and one of the strike F-4Ds, crewed by Lt Col Clayton Squier and

`GIB’ 1Lt Michael Muldoon of the 435th TFS, engaged four MiG-17s head on. The

jets passed a mere 200 ft from his Phantom II, Squier cooling an AIM-4 as he

chandelled in afterburner to pursue the enemy.

He positioned his jet for a stern attack on the trailing

MiG, and the red and white Falcon sped away from the F-4 and exploded in the

tail section of the target aircraft, which began to trail thick, grey smoke.

Squier then broke off to evade cannon fire from other MiGs that had assailed

him and his wingman as he was launching his AIM-4.

Perched above the strike force in a MiGCAP flight was F-4D

`Tampa 01′ of the 433rd TFS, flown by Maj Bernard J Bogoslofski and Capt

Richard L Huskey (`GIB’). This crew decided to dive and pursue the 923rd FR

MiG-17 that was chasing Squier’s wingman, `Olds 02′. Curving after the MiG in a

tight left turn, Bogoslofski held it in his gunsight pipper through some deft

manoeuvring and then set fire to the jet’s left wing with his 20 mm SUU-23/A

gun pod. The other `Tampa’ crews saw the pilot (probably Nguyen Hong Diep) take

to his parachute.

Another Falcon kill occurred on a similar Rolling Thunder

strike on 18 January, but on this occasion two F-4Ds were also lost, including

the MiG killer, `Otter 01′. Its crew, Maj Kenneth A Simonet (who had fought

with the US Marine Corps in World War 2, joined the Army post-war and

transferred to the USAF in 1952) and `GIB’ 1Lt Wayne Ogden Smith became PoWs

until March 1973.

With a MiGCAP flight reduced to a single element by ECM

malfunctions, the four `Otter’ F-4D strike aircraft had taken on a persistent

quartet of MiG-17s themselves. One pair hit Simonet’s wingman, Capt Bob Hinckley

and 1Lt Robert Jones (`GIB’), and they ejected from their F-4D (66- 7581) to

also become long-term PoWs. Simonet and Smith followed another MiG in a series

of climbing turns while the pilot prepared and fired an AIM-4, causing flames

to burst from the target fighter’s rear fuselage – it hit the ground with its

pilot still in the cockpit. The F-4D had, in turn, been the target for a

cannon-firing MiG-17 for much of the encounter, and it scored enough hits to

force the crew to eject from their blazing Phantom II.

The final Falcon success went to a 13th TFS crew Capt Robert

G Hill and 1Lt Bruce Huneke (`GIB’), who were flying as `Gambit 03′ in a MiGCAP

flight for a 5 February attack that cost the force an F-105 shot down by an

`Atoll’ from a MiG-21. Having briefly lost sight of the two attacking MiGs,

Hill’s flight picked them up just as their leader completed his assault on the

unfortunate `Thud’, and his wingman was seen to be climbing towards `Gambit’

flight. Capt Hill manoeuvred into the first MiG’s `deep six’ position and gave

it 100 rounds from his 20 mm gun pod. Having inflicted no visible damage, he

cooled a Falcon and fired it. The missile never completed its pre-launch

sequence, and consequently failed to guide properly. However, a second missile

hit the MiG’s rear fuselage and detonated.

For good measure Hill then followed through with a barrage

of three AIM-7Es, only one of which actually launched and guided successfully.

The second Falcon had already done its work, blowing away the rear fuselage of

the MiG-21. Hill had, by then, climbed to 40,000 ft, and his wingman warned him

that another MiG-21 had fired a K-13 `Atoll’ his way. The missile passed

horribly close to their F-4D, but it survived and was eventually preserved at

Carswell AFB, Texas.

Five Falcon kills out of 48 attempted launches during

Rolling Thunder were not enough to justify the missile’s continued use as a

major F-4 weapon, and its withdrawal proceeded as F-4Ds were progressively

re-wired for AIM-9s. On 14 July 1968 the USAF terminated the engineering

programme that would have produced a better Falcon by the following year

(although it was resumed in 1970), but the missile remained in theatre until 22

August 1972, when the USAF declared 776 AIM-4Ds `excess to SEA needs due to their

limited air-to-air capability’. It marked the end of the combat career for a

weapon that Robin Olds described as being `as useless as tits on a boar hog’.

F-4D

Including more USAF-specified equipment than the F-4C, the

F-4D prioritized ground attack and changed the secondary armament from the US

Navy’s AIM-9 Sidewinder to Hughes’ AIM-4D Falcon following “Dancing

Falcon” tests at Eglin AFB in 1965. The F-4C’s primitive ground-attack

capability was enhanced by a new AN/APQ-109A radar including solid-state

components and an air-to-ground ranging mode. A wider range of ordnance,

including guided air-to-ground weapons such as GBU-9 HOBOS, AGM-12 Bullpup, and

AGM-65 Maverick could be carried, and an ASG-22 lead-computing gunsight was

added. AIM-9 Sidewinder wiring was restored after the AIM-4D proved unsuitable

for close combat use. Nuclear capability was kept, with up to three B61

“special stores” as a typical nuclear alert warload.

USAF F-4D deliveries of 793 aircraft began with a batch for

the USAFE (United States Air Forces in Europe)-based 36th TFW in March 1966 and

continued into April 1968, with further export production of 32 for Iran until

September 1969. It entered combat use with the 555th TFS at Ubon RTAFB in May

1967. Seventy-two had ITT AN/ARN-92 LORAN-D equipment installed, and most of

these were also supplied to the 8th TFW at Ubon. LORAN-D, identifiable by a

large “towel rack” on the aircraft’s back from mid-1969, could be

linked to the aircraft’s ASN-63 inertial navigation system and bombing computer

to calculate the F-4D’s position with sufficient accuracy for precision

night-time bombing, or for more accurate navigation where the LORAN beacon

system was available.

Twenty-two F-4Ds received an important addition from late

1968 in the form of AN/APX-80 Combat Tree. This was able to interrogate the

SRO-2 IFF (identification friend or foe) transponders in MiGs, confirming their

identity codes at up to 60 miles for attacks with AIM-7 missiles beyond visual

range. Wartime rules in Southeast Asia generally required potential enemy

“bandits” picked up on radar to be approached for visual

identification, thereby losing the advantage of long-range missiles. With

Combat Tree this was not required, although officialdom was still reluctant to relax

the rules. Similar equipment was later fitted to the majority of USAF F-4Es,

and it was used by Iranian F-4s in the Iran-Iraq War. Users: USAF, Iran,

Republic of Korea.