The campaign of Guadeloupe and Martinique, January–May 1759

During this period of ‘phoney war’ there was one notable

success. To sever all communications between Basse Terre and Grande Terre and

so prevent any aid from reaching the guerrillas, the English had to capture

Fort Louis. By begging a few companies of Highlanders from Hopson to add to his

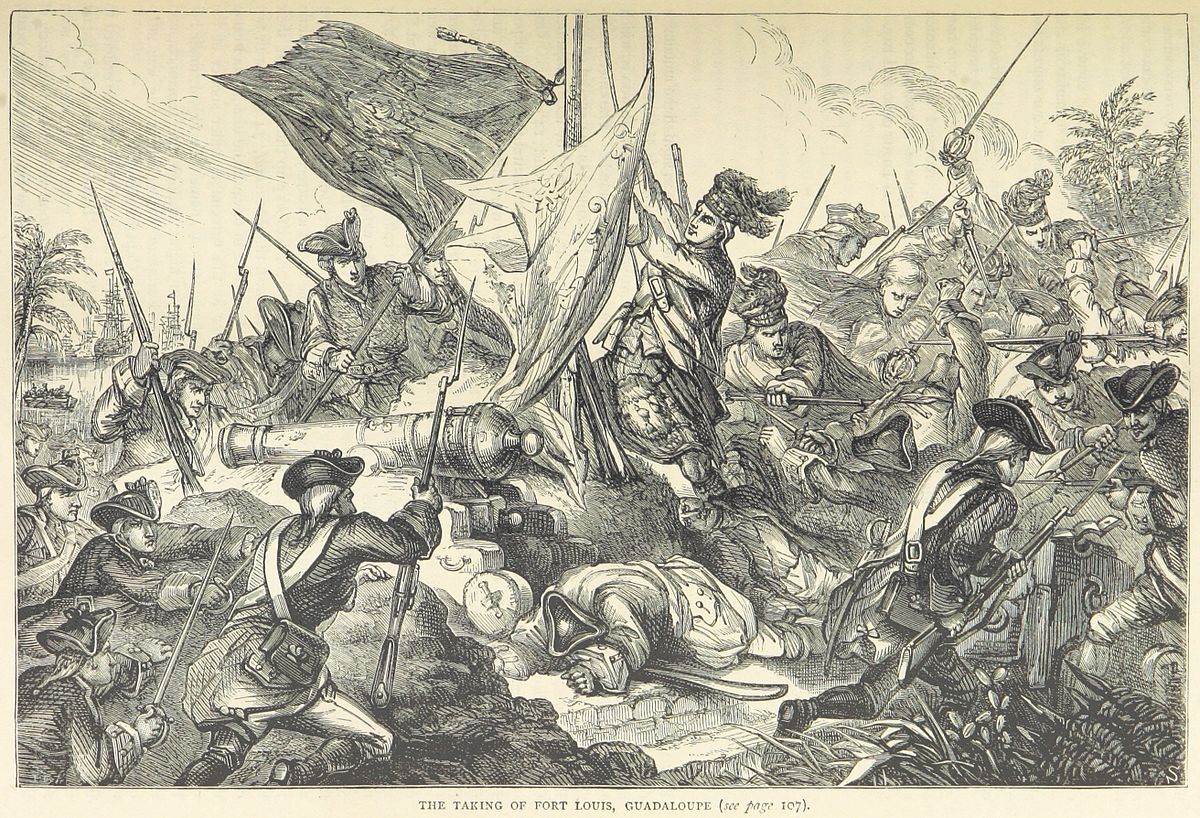

own marines, Moore thought he had the strength to do it. On 6 February the

commandos set sail and on the 13th the military action began. For six hours

Moore’s task force bombarded Fort Louis and took out both the shore batteries

and the four-gun redoubts on each of the nearby hills. Initially all went to

plan, and the Highlanders and the marines of the landing party were happy to

watch while the two ships of the line blew the fort apart. But once the assault

party clambered into the flat-bottomed landing craft – each carrying

sixty-three men, rowed with twelve oars and drawing no more than two feet of

water – the barrage was lifted for fear of hitting the invaders with ‘friendly

fire’. Whereupon hundreds of French troops reoccupied the battered positions

and opened such a heavy fire that the Colonel of marines ordered the boats to

retreat.

This led to one of those bad-tempered scenes that should act

as a cautionary tale for triumphalist theorists of combined operations. As the

flat-bottoms returned alongside HMS Berwick, the irascible commodore Captain William

Harman shouted: ‘Don’t give the damned cowardly felloes a rope.’

Enraged, Captain William Murray of the Highlanders stood up

and yelled back: ‘Captain Harman, we are under command and were forced to obey,

but rest assured that you shall answer to me for the expression you have used.’

Not fancying a duel with a claymore-wielding Highlander, Harman blustered that

he was not referring to the Highlanders but to the marines. Yet Murray was so

indignant that he ordered his boats to put about for the shore; the marines

were then shamed into following him. As Fort Louis suddenly seemed to burst

into spontaneous combustion – actually the pent-up impact of yet more deadly

carcasses – the Highlanders and the English marines waded ashore under cover of

the thick pall of smoke. They too had been pent up – cramped in readiness for

five hours in the longboats – but now they surged through the foam with gusto, making

for the sandy strand.

There were some nasty moments when they hit the

booby-trapped shoreline – for the French had driven pilings into the seabed and

interlaced them with mangroves, which acted as a home for the dreaded Anopheles

mosquito; there was therefore a chance of malaria at the very moment of

securing a beachhead. But finally the beachhead was secured and the marines and

the Highlanders, who could have been deadly enemies just thirteen years earlier

in the last Jacobite rising, came boiling out of the foam like sea monsters. To

their consternation, French veterans and black irregulars heard the dreaded cry

‘Claymore’, as the Highlanders were on them in a trice with broadsword and

bayonet. Lieutenant Grant of the Black Watch, who ached to be a hero, came a

spectacular cropper. ‘Getting out of the boat, I stumbled over a stone and fell

forward into the water. My servant, thinking me mortally wounded, seized me and

was dragging me on shore, in doing so he scraped my shins against the grapwall.

We all rushed on pell-mell, and the French ran like hares up the hill at the

back of the battery.’ Not without some deaths among the landing party by dusk

the deed was done and Basse Terre could no longer be reinforced from the other

side of the island. But it had been a grim affair, with terrible wounds inflicted.

The British did not open fire with their muskets until the French were ten

yards away, at which range the volley was devastating and murderous. All in

all, it had been a close-run thing. As Grant rightly remarked of amphibious

operations: ‘Of all species of warfare that of landing is the most unpleasant

[as]

you present a mark for your enemy and you are not in your element.’

Yet as long as the ailing Hopson lived, and more and more

men went down to tropical disease, stalemate was still the most likely

long-term result. Again Moore chafed and fretted at the lack of action. But at

last, on 27 February, his prayers were answered when the despised Hopson

succumbed to fever. His replacement, General Barrington, whom Pitt had

originally wanted to command the expedition, proved as energetic as Hopson had

been listless, although from the first day of his command he had a mountain to

climb. Moore and Barrington, who enjoyed an amazing unanimity on the way

forward, agreed that the next step was to transfer the bulk of the force to

Fort Louis, leaving just a garrison of 500 to oversee Basse Terre. Leaving

behind one battalion and transferring the worst of the sick cases to Antigua,

the commanders effected the move on 11 March, after having been at sea for a full

four days, beating up against the trade winds. To mask their departure from

Basse Terre they used a ruse worthy of Greek mythology, for Barrington ordered

tents struck and huts built as though they were settling in for a long stay.

They were now in a race against time in a double sense: they had to complete

the conquest of Guadeloupe before the hurricane season and while they still had

a credible army. Tropical disease seemed to become more virulent every day, so

that by the time they landed at Fort Louis, their effectives numbered no more

than 1,500.

Scarcely had the British landed at Fort Louis than they

received a piece of dramatically bad news. Despite the urgings of many of the

ministers on Louis XV’s Council, who despaired of ever making inroads against

British seapower and wanted to concentrate on the war in Europe, the King had

sent Admiral Maximin de Bompart to the Leeward Islands with a powerful

counterattacking task force, comprising eight ships of the line, three frigates

and a battalion of Swiss and other troops. Even though the British enjoyed the

incontestable advantages of naval dockyards in the West Indies and being

provisioned from North America, Versailles was determined that Martinique would

not be abandoned without a fight – the ministers were of course unaware that

the British had now switched operations to Guadeloupe. Moore and Barrington

were placed in a peculiarly difficult position by this new development. With

the hurricane season approaching, Moore would soon have to detach some of his

warships for convoy duties and the protection of the homeward merchant fleet.

Even worse, when Barrington opened Pitt’s sealed instructions to Hopson, he

read that Pitt ordered the Highlanders to be sent to North America once the

Martinique operation was complete. If he stuck to the letter of the orders,

Barrington would leave himself far too weak to maintain himself against

Bompart’s incursions.

Yet another of the numerous councils of war that beset this

West Indies expedition was convened. The idea of taking the offensive and

blockading Bompart in Martinique was ruled out, on the grounds of supply and

communication lines; for a start, there could be no search-and-destroy mission

against the French armada without an adequate water supply, which not even the

troops at Fort Louis had. Instead the commanders hit on the idea of

concentrating the British fleet at Prince Rupert’s Bay in the north of the

neutral island of Dominica so that it could intercept any French move against

Fort Louis. Meanwhile Barrington, aware that he was vulnerable at Fort Louis to

possible French attacks from a number of directions, opted for the strategy of

offence as the best means of defence. He reasoned that the enemy could never

unite for a push against Fort Louis if he kept them disunited by striking at

several points at the same time; accordingly in the third week of March he sent

600 men to attack the towns of Le Gosier, Ste Anne and St François

simultaneously. The strategy was a brilliant success and the thrust against Le

Gosier even produced an unexpected bonus when the jubilant attackers pressed on

and took in the rear a French force moving against Fort Louis. Barrington

followed this up with a brilliantly executed war of movement, continually

harrying the French, forever appearing in their rear when they were expected in

the van, continually switching the angle of attack and the military objective.

The French became more and more demoralised, and desertions from the militia

reached record levels.

By the beginning of April Barrington was satisfied that he

had completed the first two phases of his campaign. He had wiped out resistance

on the leeward side of Basse Terre and had crushed the defenders on Grande

Terre even more effectively. There remained the windward side of Basse Terre,

the most populous area and the region where all the richest plantations were

located. Barrington had done the difficult parts first, for this final phase

favoured conventional forces more than the other two phases. A gently rising

coastal plain extended from one to three miles to the foothills of the mountains,

and on this fertile paradise between the sea and the peaks lay a series of

wealthy sugar plantations that probably generated more wealth per acre than any

other terrain in the world in 1759. On 12 April the British disembarked some

1,450 men at Arnouville. A hard-fought action followed, with British

artillerymen and the Highlanders particularly distinguishing themselves. They

won the day but left fourteen of their men dead on the field and carried off

fifty-four wounded. The French retreated only slightly before digging in again.

They proved doughty defenders, pegging the British back to an advance of just

two miles a day. Yet in the end the combat between regulars and militiamen in

open terrain could have only one ending. On 21 April the brave but demoralised

defenders finally surrendered. The formal capitulation was signed on 1 May,

allowing for an immediate exchange of prisoners.

Incredibly, the very next day (within hours of the capitulation

according to some melodramatic reports) Bompart suddenly landed at Ste Anne,

now no more than a burnt-out shell after its recent destruction. He arrived

from Martinique with his fleet, 600 Swiss regulars, spare arms and ammunition

for another 2,000 fighters and a large force of irregulars, described in some

reports as ‘2,000 buccaneers’. Whether these militiamen and volunteers quite

numbered 2,000 or in any way merited the bloodthirsty (and at this date

somewhat anachronistic) description of buccaneers is doubtful, but the fact

remains that they made up a formidable fighting force. Learning of the

capitulation and the prisoner cartel, Bompart apparently tried to persuade the

French Governor of Guadeloupe, Nadau du Treil, to find some technicality for reneging

on the deal, but du Treil refused. Bompart accepted the inevitable and sailed

back to Martinique. Learning of his arrival to the east, Moore tried to get his

ships under way to bring Bompart to a decisive action, but the winds were

against him and he spent five frustrating days trying to reach the island of

Marie Galante. But not even a Nelson could make easting against the trade

winds, and in fifty-seven hours Moore’s ships managed to beat eastward just six

miles. What had happened? How was Bompart able to sail from Martinique to

Guadeloupe and back again without being intercepted? Moore’s main mistake was

to base himself at Rupert’s Bay in Dominica. His critics said he should have

sailed for Martinique and attacked Bompart at Fort Royale, but Moore knew the

strength of the defences there and did not want to tangle with an enemy fleet

and shore batteries. That decision was sound enough, but basing himself at

Rupert’s Bay meant that Moore lost contact with the French. The usual view is

that he should have positioned himself to windward of the enemy and within

sight, ready to pursue wherever Bompart went. But Moore thought he had all the

options covered. He expected Bompart either to attack Basse Terre and Fort

Louis or to proceed to Jamaica. Nobody on the British side had considered the

possibility that the French might land on the windward side of Grande Terre. So

it was that Moore failed to intercept Bompart both on the outward and return

journey between Martinique and Guadeloupe. Moore had got to the windward of the

enemy’s putative objective but not of the enemy himself. His later

protestations were of the same kind as those of the punter who complains that

the favourite in a horse race did not win: reason, logic and the form book did

not prevail. Bompart defied all normal expectations by passing round the

southern end of Martinique instead of coming inside the islands.

The British had won the battle for Guadeloupe, but it had

been touch and go. If the French commanders had cooperated better and shown

more energy, the British would have been defeated. If Bompart had arrived just

a day earlier, the balance of forces would have shifted irremediably in the

French favour. Barrington admitted that he was at the limit of his resources

and could not have fought much longer. He told Pitt that disease was making

such inroads on the expeditionary force that he would soon not have a credible

fighting body and he therefore dreaded the consequences. Aware that he could be

criticised for having agreed to very lenient terms of capitulation, he wrote to

the Prime Minister on 9 May: ‘I hope you will approve of the arrangements for I

can assure you that by force alone I could not have made myself master of these

islands nor even of maintaining a garrison at Fort Louis, which I would have

had to blow up after withdrawing the garrison . . . [whatever troops I left

behind] would have succumbed as soon as my army departed.’ Whatever criticisms

can be made of Moore, Barrington emerges with a clean sheet from the Guadeloupe

campaign. He has been criticised, anachronistically, for not fighting a war of

attrition instead of accepting a negotiated surrender. But it is simply a fact

that eighteenth-century armies aimed at victory but not annihilation, and still

less at unconditional surrender. Moreover, if Hopson had simply accepted a

truce and allowed experienced negotiators time to arrive, Bompart’s force would

have reinforced the defenders and ultimately defeated him.

Meanwhile new orders arrived from London. Pitt, having

learned about the switch from Martinique to Guadeloupe, ordered Barrington to

take the island of St Lucia and to that end rescinded his previous orders about

sending the Highlanders to Louisbourg. Barrington, though, did not have nearly

enough manpower for the conquest of St Lucia. He sent the Highland regiments to

Louisbourg, having first conducted a face-saving exercise by conquering the

small islands in the Guadeloupe group – Marie Galante, Deseada, The Saints,

Petit Terre. On 25 July he sailed for home with three battalions.

Moore moved on to Antigua to protect merchant navy commerce,

which had been preyed on incessantly by the privateers once they saw the Royal

Navy preoccupied with Bompart. Moore was not able to make any further contact

with his French rival, but sailed for home with a huge convoy of 300

merchantmen in September. He took with him a blackened reputation. Not only was

he in bad odour for failing to search and destroy Bompart but, as the Barbados

authorities complained bitterly to London, he had failed to protect their

commerce, as the facts proved: the privateers had taken ninety British ships

between January and July. Moore’s defence was twofold. Dealing with the

privateers was a Herculean labour against the hydra’s heads, as the terms

negotiated required a simple exchange of prisoners; since the corsairs had to

be released as soon as they were caught, they simply went back to their

piratical activities. As for his unpopularity in Barbados, this was because

Moore had tried to find out who was running the illegal but highly profitable

slave trade between Barbados and St Vincent as well as the commerce in

foodstuffs to the neutral islands which the French had occupied.

The armed forces of George II had learned a lot from their

tropical campaign in the West Indies. Richard Gardiner of the marines testified

that the Martinique and Guadeloupe campaigning was particularly arduous. The

troops were ‘exposed to dangers they had never known, to disorders they had

never felt, to a climate more fatal than the enemy, and to a method of fighting

they had never seen’. If by the end of the campaign they knew nothing about

fighting irregulars in the bush, they also had no answer to the ravages of

yellow fever and other diseases. From Barrington’s departure after the conquest

of Guadeloupe in June to October 1759 eight officers and 577 men had succumbed

to disease while performing nothing more strenuous than garrison duty. In such

a context admirers of the landscape were rare, yet George Durant, one of the

British officers, contributed to the growing cult of the picturesque, finding the

island ‘prospects both noble and romantic . . . hills whose tops reached the

clouds, covered with stately woods of ten thousand different shades of green’.

Yet in the short term the many critics of Moore took a back

seat, while euphoria in London at the conquest of Guadeloupe was given free

rein. Newcastle was in full burbling mood, writing to the Admiralty of ‘great

good news . . . I want something to revive my spirits and this has done it . .

. must be great in its consequences . . . hope will refresh our stocks . . .

great affair.’ Pitt remarked more sparingly: ‘Louisbourgh and Guadeloupe are

the best plenipos at a Congress.’ The news was particularly welcome as Pitt’s

government had been under great strain through financial crisis. Ministers

could not agree which taxes should be earmarked to finance the massive debt

voted so facilely by Parliament the previous autumn; and the kingdom was

seriously short of specie, since gold and silver coins had been exported in

large numbers to maintain the war in Germany and North America. Financial

confidence was shaken and government bonds began selling at the steepest

discounts since the Glorious Revolution. The conquest of Guadeloupe proved a

massive shot in the arm, even though London was at first slow to appreciate the

wealth of the sugar islands. The 350 plantation owners of Guadeloupe and Marie

Galante began shipping their sugar, coffee, cocoa, cotton and other products to

Britain in return for much-needed slaves and manufactured goods. Within a year

of the conquest, from 1759 to mid-1760, Guadeloupe sent 10,000 tons of sugar,

valued at £425,000, to Britain and imported 5,000 slaves plus wrought iron and

other manufactures. Guadeloupe also supplied Massachusetts rum distillers with

half the molasses they needed – three times the volume exported from Jamaica.

If Britain achieved the serendipity of riches gained while

pursuing what were primarily military ends, France by contrast was sunk in the

deepest gloom by the news from the West Indies. Marshal Belle-Isle at the War

Office confessed himself devastated by the loss of Guadeloupe. The French took

the setback hard and went looking for scapegoats. They fastened on the Governor

of Guadeloupe, Nadau du Treil, whom they blamed for signing the articles of

capitulation to Barrington. Du Treil received a sentence of life imprisonment.

But the real culprit, François, Marquis de Beauharnois, Governor of Martinique,

who took three months to decide to help Guadeloupe, even though the island was

just a few hours’ sail away, escaped serious censure on the grounds that he had

repelled an attempted British invasion of his island. The French position in

the West Indies was bedevilled by a number of factors, principally the lack of

inter-island cooperation and the militia system. Because of the class system on

the islands (out of Guadeloupe’s population of 50,000 more than 80 per cent

were black slaves), most of the Frenchmen were grandees of one sort or another,

who would not take orders willingly; it was a classic case of too many chiefs

and not enough French West Indians. And the different islands failed to

cooperate with each other largely because militiamen and their native levies would

not serve ‘abroad’ – that is, away from their own islands.

Bompart, who eventually returned to France in November and

slipped through a British naval blockade to reach Brest, is a good source for

the endemic French weaknesses. Two weeks after anchoring in Fort Royale, on 20

March, he wrote to the Navy Minister Berryer as follows: ‘I have found everything

chaotic and disorganised, the people terrified, order and hierarchy virtually

annihilated . . . I have not been consulted or warned about conditions here and

the governor lets everything go to pot and does nothing.’ Two months later,

after the capitulation, Bompart was even more acidulous, wrote despairingly of

the loss of French prestige and spoke of the way the neutral islands were going

over wholesale to the British side. A letter to Berryer on 22 May contains the

following: ‘Dominica is now removed from the orbit of His Most Christian

Majesty and has signed a pact of neutrality (i.e. friendship) with the British.

The French on that island sell our enemies their best produce . . .

Guadeloupe’s favourable economic position now under the British is making

people in Martinique think . . . Grenada now has a glut of sugar and the French

West Indies are now in economic crisis, since exports to Canada and Louisbourg

have ceased.’ Now the only outlet for French sugar and coffee was France

itself, with whom the islands had secure communications only in neutral Danish

or Dutch shipping. And even the neutral flag did not protect such shipping

against British privateers. Needless to say, British tribunals invariably

declared such captures lawful prizes.

The letter to Berryer is worth following up, for it

expresses the fundamental truth that Guadeloupe did very well out of the

four-year British occupation from 1759 to 1763. The planters in the islands of

the British West Indies wanted and expected draconian treatment of the

conquered Antilles isles and required as an absolute minimum some of the

following: expulsions, high taxation, oaths of allegiance, land expropriation,

a ban on the production of sugar, cocoa and coffee. Yet almost the reverse

happened. In the four years of their occupation, the British developed

Pointe-à-Pitre as a major harbour, opened English and North American markets to

Guadeloupean sugar and allowed the planters to import cheap American lumber and

food. After being boosted by imports, Guadeloupe overtook Martinique’s slave

population, and until 1763 half of all French slave carriers had Martinique and

Guadeloupe as their destination (the other main ones being Guyana and Grenada).

To general stupefaction in the islands, the French planters were not expelled.

How was this possible? The main reason was that Moore and Barrington allowed

exceptionally generous terms at the surrender, which in turn reflected

uncertainty in London as to whether Guadeloupe was to be taken over as a

permanent conquest or simply subject to temporary occupation.

In the articles of capitulation, Moore and Barrington

allowed the Guadeloupeans to be neutral, to have complete religious freedom and

security for both church and lay property, to enjoy their old laws, to pay no

more duties than at present and, if Guadeloupe was retained after the peace, to

pay no more than 4.5 per cent taxes on exports (the lowest rate in the Leeward

Islands) – in effect granting the island most-favoured-nation status; moreover

the people would not have to provide barracks for the British army or supply

forced labour – all labour would be paid for and blacks employed only with the

consent of their masters. This last was a remarkable concession, as it put

Guadeloupe planters ahead of any other slave-owners in the West Indies, whether

British or French. As an added bonus, it was agreed that anyone free of debt

could leave at once for Martinique and/or send their children to be educated in

France. The most remarkable concession of all was Article Eleven of the

capitulation which promised that, until peace came, no British subject could

acquire land in Guadeloupe.

Guadeloupe’s position improved almost magically once removed

from the domination of Martinique. American merchants supplied all the goods of

which the island had hitherto been starved. The only problems remaining for the

French planters were how to export coffee to England and how to import wine

from France, and they solved these easily by smuggling. Slave merchants did

particularly well, and there were 7,500 more black slaves on Guadeloupe in

February 1762 than there had been in 1759. In the general atmosphere of bonanza

the British authorities had one overriding problem: tightening up the nexus

that bound debtors and creditors. Under the lax pre-1759 laws, creditors had

rarely been paid, and the British feared that if they advanced credit to the

planters and Guadeloupe was returned to France as part of a general peace, they

would not get their money back. Indeed, certain shrewd operators in the French

mercantile community had worked out that, having escaped their French creditors

when the British took over, they might in turn escape their British ones once

peace came, and thus complete a double-whammy of debt evasion.

Soon the prosperity and special concessions made to

Guadeloupe led to jealousy and bitterness in the other islands of the West

Indies, both British and French. Barbados began to complain that market prices

had increased because of the huge demand in Guadeloupe, while in London absentee

West Indies planters were angry at plummeting prices when Guadeloupe sugar

starting flooding the market in 1760. Martinique was deeply resentful of the

favourable deal obtained by its fellow countrymen in Guadeloupe, and this may

have been a factor in the speedy surrender of Martinique to the British in

1762. Martinique, however, managed to live on the proceeds of privateering in

the three years between the first and second British attack, partly because its

own corsairs were more successful after 1759 than previously and partly because

British privateers, discouraged by a recent decision in the Court of Prize

Appeals in England, largely ceased their depredations; moreover, the Royal Navy

blockaders spread themselves too thinly among the islands. Besides, Versailles

belatedly decided to do something for the Antilles and, as a reward for

repelling the British, Martinique was opened to neutral shipping after February

1759; no special trading licence was required and the normal fee of 3,000

livres was waived. For all these reasons Martinique was able, if not quite to

hold its own against Guadeloupe, at least to enjoy, paradoxically, greater

prosperity after 1759 than before.

The West Indian campaign was an unusual venture in

eighteenth-century terms, when amphibious operations were rare. Anachronism is

the enemy of history and 1759 can be understood only if we realise how far the

mentality of warriors of that time was from the twentieth-century sensibility,

inured to combined land and sea assaults like those in Operation TORCH in North

Africa in 1942, the assault on Sicily in 1943, the D-Day landings in Normandy

in 1944, to say nothing of an entire chapter of seaborne invasions in the

Pacific War (in the Gilberts, Marshalls, New Guinea, the Philippines and Okinawa).

Nonetheless, all the elements of modern combined operations were there in

primitive form in 1759: naval bombardments, flat-bottomed naval craft, perilous

landings in the teeth of underwater obstacles, beachheads secured only at great

cost in human life.

Although Pitt’s conception of Guadeloupe as a trading

counter for Minorca inspired the enterprise, when peace negotiations to end the

Seven Years War began in 1762, the British proved remarkably reluctant to give

up their acquisitions in the French West Indies. There was a powerful lobby

that wanted to hang on to Guadeloupe and was even prepared to return Canada to

France if that could be accomplished. The Canada-versus-Guadeloupe debate

became one of history’s most famous controversies. There are even those who

argue that if Britain had retained Guadeloupe and returned Canada to France,

the impossibility of an independent United States would have been doubly

determined, both by the French presence in North America and by the absence of

the French seapower in the Caribbean that ultimately made Yorktown in 1781

possible. 1759 changed world history in more ways than one.