The Challenge

On 15 June 1888, the twenty-year-old Kaiser Wilhelm II was

crowned emperor of Germany. Although capable of moments of brilliant insight,

Wilhelm II was infamous for his obnoxious arrogance, uncontrollable temper and

erratic decision making. Intensely Anglophobic, he despised the British Empire

and felt that Germany was being denied ‘a place in the sun’ by a conspiracy of

British and French interests. Wilhelm II was determined to redress this

balance.

Germany began to build its colonial empire in the 1890s

using a handful of warships, but Wilhelm II dreamed of creating a fleet that

would one day topple the Royal Navy itself. In 1897 he appointed Konteradmiral

Alfred von Tirpitz as Secretary of the Imperial Navy Office. Tirpitz shared

Wilhelm II’s naval ambitions and had the political skill to steer the proposals

through the Reichstag. Within a year, Germany had passed the First Naval Bill,

which called for the construction of nineteen battleships by 1904. In 1900,

Tirpitz used the pretext of strained Anglo-German relations as a result of the

Boer War to increase the provision of battleships to thirty-eight vessels.

The gauntlet had been thrown down to Britain. For almost a

century the Royal Navy had been the undisputed master of the oceans. Lord

Horatio Nelson’s legendary victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 had

established such an overwhelming sense of British naval superiority that no

other major power had dared to challenge it – until now.

The British government quickly perceived that German naval

building was not merely a danger to the empire, but, by virtue of Germany’s

geographic position, represented a grave threat to Britain itself. The Royal

Navy responded to German construction in kind. The first great arms race of the

twentieth century had begun.

In 1906 the Royal Navy changed the terms of the contest with

the launch of the revolutionary battleship Dreadnought. This vessel was faster,

better armoured and more heavily armed than any ship then afloat. Dreadnought

was so advanced compared to her rivals that from that point on battleships

would be classed either as modern dreadnoughts or outdated pre-dreadnoughts.

Some strategists in Britain hoped that the launch of

Dreadnought would convince the Germans that they were beaten and thus end the

ruinously expensive contest. They had reckoned without the determination of

Wilhelm II and Tirpitz. Germany saw the launch of Dreadnought as an

opportunity, for although the new ship had rendered the German fleet obsolete,

it had also done the same for the vast majority of existing British

battleships. The balance sheet was cleared and it would now be a contest to see

who could build dreadnoughts fastest. The arms race intensified in the years

that followed as both sides strained to manufacture ever greater numbers of modern

warships.

From Dreadnought onwards, each successive class of ships was

bigger, faster, and more powerful than the last. Covered in thick steel plate,

driven by the largest and most powerful engines available and carrying the

heaviest guns it was possible to mount, the modern battleship was the most

powerful weapon system in the world. The dreadnoughts were supported by

battlecruisers, formidable vessels of comparable size that were built to

emphasise speed and armament at the expense of armoured protection. In

addition, both navies constructed numerous light cruisers, destroyers, and

torpedo boats to support the heavy ships.

The naval race strained finances to the limit, but it was

Britain which emerged as the clear leader. By the outbreak of war the Royal

Navy had launched twenty dreadnoughts, with another twelve under construction,

compared to thirteen German dreadnoughts, with seven being built.

Germany now faced a serious strategic problem. During the

arms race, Tirpitz had deluded himself with the hope that the fleet would be a

deterrent weapon that would intimidate Britain and convince it to stay neutral

in the event of war. At its heart the policy was a bluff – and the bluff was

abruptly called in August 1914. The German Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet) now

had to consider how to overcome the numerically superior Royal Navy.

The Balance of Power

Although heavily outnumbered, the High Seas Fleet had some

advantages over the rival Grand Fleet. The most obvious was that it was

concentrated in the North Sea. Whereas the British had to provide vessels to

police the imperial trading lanes, the Germans could focus all their attention

on the main theatre of operations. The expectation of operating in the North

Sea had influenced German ship design. The vessels of the High Seas Fleet

tended to be less heavily armed but more heavily armoured than their British

counterparts. This trade-off was considered viable given Germany’s numerical

disadvantage. Each vessel was precious and therefore survivability was of foremost

importance.

There was no doubt that the German ships were highly

resistant to damage. However, this fact was well known to the British

Admiralty, and during the naval arms race a number of measures had been taken

to nullify the German advantage in armoured protection. The British had

increased the calibre of their heavy guns so that their latest vessels mounted

mighty 15-inch batteries. More importantly, the British had also given serious

thought to the design and effectiveness of their armour-piercing shells. Firing

exercises had discovered numerous flaws with existing British ammunition. The

most serious was the tendency of the shells to burst against armour plating

rather than tearing through the steel and exploding in the interior of the

enemy ship as they were intended. The problem was traced to a combination of

inadequate fuses and unreliable explosive.

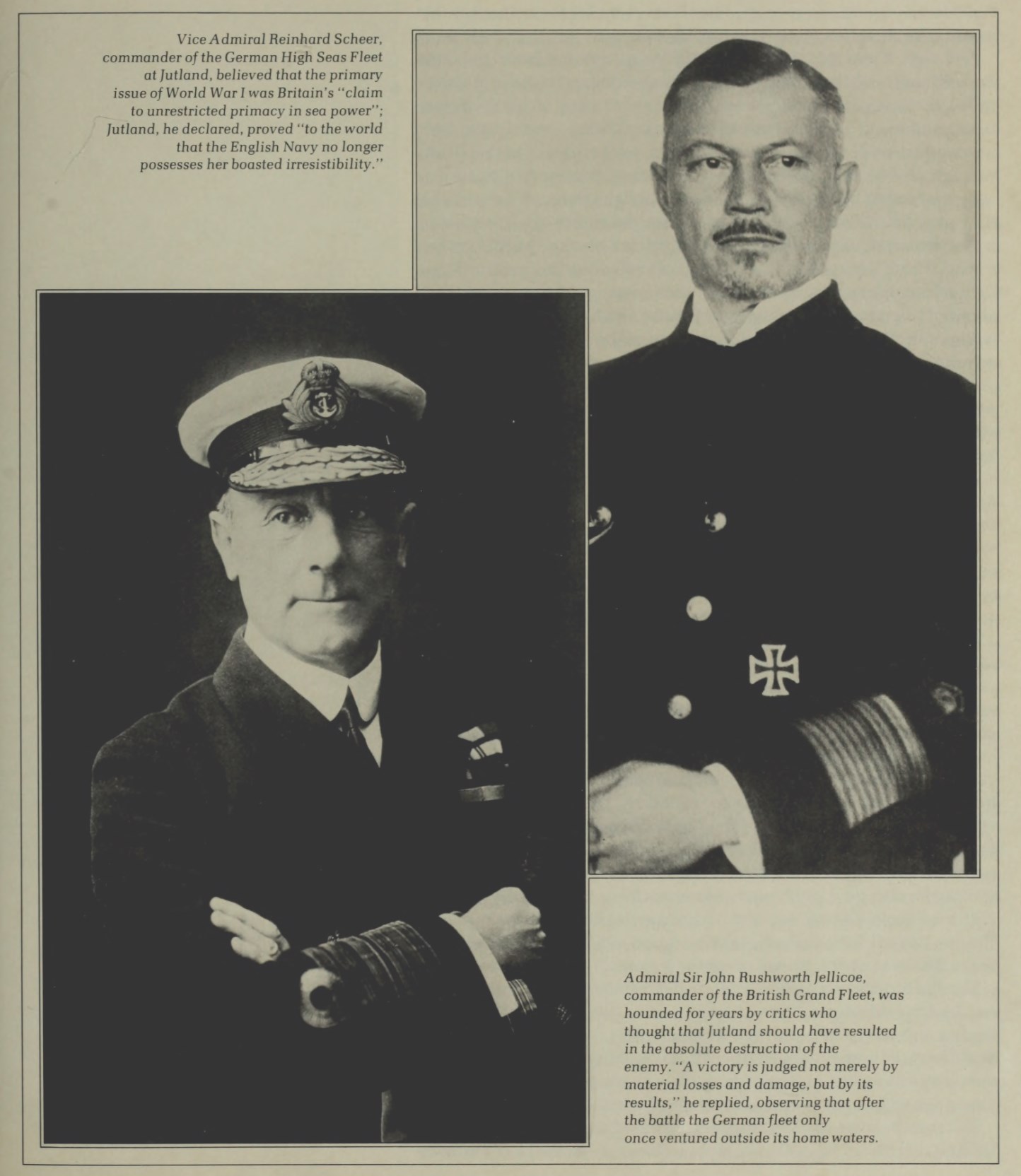

Director of Naval Ordnance and future commander of the Grand

Fleet John Jellicoe was at the forefront of demanding improvements in

ammunition. Although promotion soon took him away from his role with the

ordnance department, he continued a vigorous campaign for better shells. The

Admiralty reacted with the tardiness typical of large bureaucracies but

Jellicoe refused to let the matter rest. The reform of the design, testing, and

procurement process for new shells was painfully protracted but on the very eve

of the war a new type of armour-piercing shell was finally accepted. Jellicoe

was well pleased with the improved ammunition, claiming that it ‘certainly

doubled’ the effectiveness of the Grand Fleet’s big guns. However, production

delays caused by the demands of war meant that it took until mid-1915 for the

fleet to be fully equipped with the new shells.

At the same time that ammunition was being improved, a

fierce and often ill-tempered debate was raging over the best methods of fire

control. At the heart of the issue was the firebrand Captain Percy Scott, who

campaigned for centrally directed fire control and a wholesale reform of

gunnery training. An abrasive and arrogant character, Scott nevertheless drove

his reforms through and conclusively proved the value of his methods during

gunnery trials. Admiral Sir John Fisher offered a blunt assessment of Scott: ‘I

don’t care if he drinks, gambles and womanises; he hits the target.’

A particularly important reform pioneered by Scott was the

adoption of a ‘double salvo’ system of fire. Under this system a capital ship

would fire two quick salvos spaced several hundred yards apart. The fall of

shot would be observed and appropriate corrections made: for example, if one

salvo fell short and the other went over the target then the distance clearly

lay in the middle and could be quickly calculated. Once the double salvo had

acquired the range the guns would switch to rapid fire and smother the target

with shells. The advantage of double salvo was that it allowed guns to zero in

far quicker than if the range was determined using a single salvo.

The combined effect of these reforms was considerable. The

Grand Fleet possessed more numerous and noticeably heavier guns than the High

Seas Fleet. It was clear that in a fleet encounter the mighty broadsides of the

British ships would prove decisive. As a result, Germany planned to fight a

klienkrieg – a ‘small war’ – using mines and submarines. These subtle weapons

would whittle away at the Royal Navy’s numerical preponderance until the number

of British capital ships was so reduced that a fleet action could be fought on

even terms.

Unfortunately for Germany, the strategy was bankrupt from

the very beginning. The Royal Navy instituted a distant blockade based on

closing the exits of the North Sea and refused to charge recklessly into German

waters which were teeming with undersea hazards. For their part, the Germans

limited their efforts to some commerce raiding and the occasional ‘tip and run’

bombardment of British seaside towns. However, the latter operations were

abandoned after the German battlecruisers of the 1st Scouting Group barely

escaped from a bruising encounter with their British opposites at the Battle of

Dogger Bank on 24 January 1915.

Forbidden by order of Wilhelm II from taking undue risks,

the High Seas Fleet spent the rest of 1915 in a state of inertia. Meanwhile,

the British blockade slowly tightened. Rationing was introduced in Germany in

early 1915. The German nation was in the grip of a British stranglehold and

only the navy had the power to break it.

The Ambush

In early 1916 a new commander, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, took

charge of the High Seas Fleet. Scheer recognised that the naval situation was

intolerable for Germany. Its attempts to use submarines to attack British

commerce had succeeded only in alienating the United States. By contrast,

Britain’s surface blockade was unrelenting and would remain so as long as the

Grand Fleet was still afloat.

Scheer proposed a new strategy. The High Seas Fleet would

take the fight to the British by returning to ‘tip and run’ attacks and

aggressive operations designed to lure the Grand Fleet into an unfavourable battle.

Scheer hoped to inflict stinging losses by ambushing isolated squadrons of the

Royal Navy and escaping before retribution followed. The High Seas Fleet would

work alongside submarines and minelayers to draw the British into ambush zones.

Yet unbeknownst to Scheer, the strategy had a fatal flaw –

the British knew his every move. In August 1914 the German cruiser Magdeburg

had run aground in the Baltic and been captured by the Russians. Onboard were

three copies of the German naval signals book and cyphers.8 The Russians shared

a copy with the British, and by November the Admiralty had established a

dedicated naval cryptography department codenamed Room 40. By 1916, Room 40

could decode virtually all German naval signals traffic. Relevant information was

swiftly passed to Jellicoe and the Grand Fleet.

Ignorant of these developments, Scheer spent May 1916

planning an ambush for the British. The fast battlecruisers of the 1st Scouting

Group would draw out the British battlecruisers and lead them on a chase that

would ultimately carry them into the arms of the German battleships. Locally

outnumbered, the British would be destroyed before reinforcements could arrive.

It was a simple and effective plan that may well have worked

– but the British knew of it before it had even begun. In the small hours of 31

May, before Scheer had even set sail, the entire Grand Fleet had left port and

was steaming towards the ambush area. Jellicoe planned to turn the tables on

the Germans. His battlecruisers, under the command of flamboyant Vice- Admiral

David Beatty, would ‘allow’ themselves to be drawn into Scheer’s trap. However,

as soon as the German battleships appeared, Beatty was to turn about and lead

them into a head-on collision with the awesome force of the entire Grand Fleet.

The trap was set.

The Chase

The Battle of Jutland started in unassuming fashion.

Beatty’s vessels were cruising in the region of anticipated German activity but

the disappointing absence of enemy ships was in danger of dampening the mood.

At 2.20 p.m. the light cruiser Galatea noticed a small tramp steamer blowing

off an unusually large amount of steam, an action consistent with suddenly

being forced to stop. Curious, the Galatea turned away from her sister ships

and approached the civilian vessel. It was a minor incident in what had so far

been an uneventful sweep.

As she approached the steamer, Galatea observed two unknown

ships approaching from the opposite direction. Several pairs of binoculars

snapped onto the newcomers and less than a minute later the signal ‘ENEMY IN

SIGHT’ was flying from her yardarms and an urgent message had been whisked down

to her wireless station. Seconds later she fired the first shot of the great

battle, hurling a 6-inch shell at the approaching German ships.

The signal had an electrifying effect on Beatty’s squadron

of six battlecruisers – Lion, Princess Royal, Queen Mary, Tiger, New Zealand,

and Indomitable. With Beatty’s flagship Lion in the lead, the battlecruisers

swung around towards the approaching enemy. The call ‘Action Stations!’ was

sounded and dense smoke poured from the funnels of the fast, sleek ships as

they worked up to their fearsome top speed of some twenty-seven knots.

Following close behind were the four battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron – Barham,

Valiant, Malaya, and Warspite – under the command of Rear-Admiral Hugh

Evan-Thomas. Ships of the Queen Elizabeth class, they were known as ‘super

dreadnoughts’ due to their cutting-edge combination of armour, guns, and speed.

Due to their high top speed of twenty-five knots the Queen Elizabeth class were

the only heavy units capable of operating alongside battlecruisers; however, in

any prolonged chase they would inevitably start to lose ground.

Fortunately for the British, Beatty had taken account of 5th

Battle Squadron’s lower top speed and had kept the ships close to his

battlecruisers so that they would not be left behind in any sudden change of

course.9 Both battleships and battlecruisers now turned to the south-east,

increasing speed and clearing the decks for action. Union flags were hoisted at

the main mast and numerous white ensigns were run up the yardarms. Malaya

raised the flag of the Federated States of Malaya. Ten formidable warships were

now surging through the sea to meet the Germans head on.

Their opponents were the five battlecruisers of Rear-Admiral

Franz von Hipper’s 1st Scouting Group – Lutzow, Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke,

and Von der Tann. A German gunner onboard Derfflinger recorded the approach of

the British ships: ‘even at this great distance they looked powerful, massive …

It was a stimulating, majestic spectacle as the dark-grey giants approached

like fate itself.’ However, Hipper remained calm. His task was not to engage in

a stand-up fight but instead to lure the British into reach of Scheer’s

battleships. As Beatty and Evan-Thomas bore down on him, Hipper reversed course

and began to race away to the south-east. The chase was on.

The range steadily decreased as the British closed in on the

fleeing Germans. Beatty’s battlecruisers had reached twenty-five knots, with

Evan-Thomas’s ships straining to keep up behind him. British and German

destroyer flotillas rushed into the ‘no man’s land’ between the capital ships,

prows bursting from the sea as they raced along at thirty-five knots. The

tension was almost unbearable. A stoker in New Zealand remembered an

‘incredible thrill’ at hearing the order ‘All guns load!’ being relayed through

the internal telephone system.

It was the Germans who began the firing. The broadsides of

their battlecruisers rippled with flame as their sent out their first salvo at

approximately 18,500 yards range – and closing fast. The British immediately

returned fire. A crewman on Malaya remembered: ‘It was the most glorious sight

and I was tremendously thrilled.’ Incoming shells ‘appeared just like big

bluebottles flying straight towards you, each time going to hit you in the eye;

then they would fall and the shell would either burst or else ricochet off the

water and lollop away above and beyond you; turning over and over in the air.’

But shells soon began to smash home. Visibility favoured the

Germans and they exploited their advantage to the full. Tiger was set ablaze

and a direct hit on Lion blew the roof off a forward turret and started a

dangerous fire that threatened to detonate the magazine – and with it the

entire ship – until the chamber was flooded by order of the fatally injured

Major Francis Harvey, who won a posthumous Victoria Cross for his action. Most

seriously of all, the Indomitable was simultaneously struck by almost every

shot of a salvo fired from Von der Tann. The damage was catastrophic: ablaze

from stem to stern, Indomitable turned away from the action and tried to open

the range, but within a minute she was engulfed in a huge explosion and

disappeared beneath the waves.

The British battlecruisers returned fire furiously but their

gunnery was wayward, for their crews were not as thoroughly trained as their

Grand Fleet comrades. However, the big guns of the 5th Battle Squadron were a

different proposition. A German crewman recalled of the Queen Elizabeths:

‘There had been much talk in our fleet of these ships … Their speed was

scarcely inferior to ours but they fired a shell more than twice as heavy as

ours. They opened fire at portentous ranges.’

The effect was swift. Fifteen-inch shells plunged down

around the German ships, causing devastation wherever they struck. All of

Hipper’s ships felt the force of this fire, but Von der Tann was hit

particularly hard. Shells wrecked her superstructure and caused serious

flooding below decks. One crewman recalled that the ‘tremendous blow’ of being

hit by a 15-inch shell made the ‘hull vibrate longitudinally like a tuning

fork’.

Although visibility favoured Hipper’s ships, the greater

weight of British fire began to tell on the 1st Scouting Group. German vessels

shuddered beneath high-calibre-shell hits that sliced through steel plate as

though it were paper. Soon Hipper’s battlecruisers were cloaked beneath the

smoke of the numerous fires that raged aboard. Von der Tann was so heavily

damaged that she could scarcely fire a single gun, but her captain courageously

kept her in the line so that the British could not concentrate fire on her

sister ships. German fire slackened as the 1st Scouting Group adopted a zigzag

pattern to try and throw off the aim of the British ships.

However, Hipper could endure such punishment as long as he

could fulfil his part of the German plan. Every minute of the chase brought the

British closer to Scheer’s battleships. The trap was about to be sprung.