As a prelude to the 1962 Geneva Accords, the royal Laotian

government and the Pathet Lao signed a cease-fire agreement on 3 May 1961. The

fighting subsided, but it did not end. After the cease-fire, and prior to

signing of the Geneva Accords, the Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese

continued to press royal Laotian forces back from positions along the

Laos-Vietnam border with raids and combat patrols. Meanwhile, the Royal Laotian

Army attempted to defend areas that had been under their control as of the 3

May cease-fire-or to retake them if lost-but took no aggressive action to

capture additional areas. During this time, prior to the signing of the

accords, there was a distinct buildup of Communist forces in the southern

Laotian panhandle that possibly indicated their intent to gain control of the

panhandle in order to infiltrate South Vietnam.

After the accords were signed, the Pathet Lao refused to

allow the International Control Commission (the body created to assure compliance

by all parties) access to areas under their control, and North Vietnam refused

to withdraw its army. In a reciprocal move, the U. S. government continued to

provide covert aid to Gen. Vang Pao’s guerilla army and Le Kong’s neutralist

forces. By the spring of 1963 the opposing forces were postured for a

resumption of hostilities on the Plain of Jars in central Laos.

From 1960 to 1963 American military operations along the Ho

Chi Minh Trail in Laos were generally confined to aerial photoreconnaissance,

and patrolling was limited to U. S.-trained Laotian tribesmen and South Vietnamese

border patrols. Given the difficulty of the terrain and the natural concealment

afforded by the forest canopy, the extent of infiltration was difficult to

ascertain. Intelligence analysts correctly concluded that the Laotian panhandle

was a conduit for a significant amount of North Vietnamese matériel and

manpower arriving in South Vietnam.

In 1963 the Laotian government received covert military

assistance from the United States in the form of small arms, mortars,

howitzers, and a few obsolete aircraft, all of it delivered by Air America, an

airline passenger and freight company covertly owned by the CIA. Under the

direction of the U. S. embassy, the CIA also managed military aid programs and

took steps to strengthen irregular forces in the non-communist area of Laos. On

19 June 1963 President Kennedy authorized actions designed to gradually

increase pressure on the Communists in Laos, but because the Geneva Accords

prohibited the United States from providing direct military aid or sending military

advisors or training teams to Laos, the T-6 and T-28 aircraft and other

matériel were shipped to Thailand. At the request of Laotian prime minister

Souvanna Phouma, Operation Water Pump deployed Detachment 6, 1st Air Commando

Wing, to Ubon, Thailand, in April 1964 to provide on-the-job training

assistance and forward air controllers to the Royal Laotian Air Force.

In addition to providing covert aid to Laos, the United

States periodically flew reconnaissance missions over Laos. When two

reconnaissance aircraft were shot down over Laos in early June 1964, Secretary

of Defense McNamara urged President Johnson to retaliate to preclude North

Vietnam from believing that the United States “talked tough, but acted

weak.” Johnson approved a retaliatory strike. Although the news of the

lost aircraft and the retaliatory strike were announced to the public, a secret

air war expanded over Laos. President Johnson ordered the reconnaissance flights

to continue, but with armed escorts. On 14 December 1964 the United States,

with the approval of the Laotian government, launched a limited air

interdiction campaign against the infiltration routes called Operation Barrel

Roll. It was part of the overall strategy of graduated response and intended to

dissuade the North Vietnamese from continuing to support the insurgency in

South Vietnam.

The Laotian panhandle was a difficult environment for air

operations. Steep forested mountains were frequently enshrouded by rain and

fog, and the earliest maps of the area were crude by any standard, creating an

obvious problem of target acquisition. McNamara queried the services about

their capabilities to locate enemy vehicles at night using aircraft equipped

with infrared sensors. The air force believed that it could develop a night

target-acquisition system using its four infrared-equipped B-57s stationed in

Thailand and South Vietnam in conjunction with improved navigational aids. The

army had the infrared-equipped OV-1 Mohawk, a twin engine turboprop Grumman

aircraft fielded in 1961. And the navy had its A-6A Intruder, an aircraft

specifically designed for night armed-reconnaissance, which was scheduled to

enter the inventory in the spring of 1965.

At the direction of MACV, the army conducted a test of the

Mohawk’s night acquisition capability in southern Laos and produced

high-quality infrared photography. But little came of the results. The air

force was more concerned with an unwarranted intrusion into what it considered

to be its the role and mission. The question of night operations was

temporarily dropped after CINCPAC, Admiral Sharp, stated that night operations

would only complement day operations. While Sharp’s comment may have been

correct in 1964, the truth changed in 1965.

The U. S. ambassador to Laos, William Sullivan, sent a

message to the Department of State describing the difficulty in finding the

North Vietnamese infiltration routes. Sullivan had spent 19 June 1965 with the

Royal Laotian Air Force commander, Gen. Thao Ma, whose pilots had flown

hundreds of sorties over the Laotian panhandle searching for the infiltration

routes and had been able to flush out truck convoys and destroy several trucks.

Ma flew Sullivan in a helicopter out to the area where U. S. jet reconnaissance

aircraft could find no sign of a road. They overflew the area at low altitude,

and in all but a few small areas the road was totally concealed. Then Ma’s

pilot landed and Ma and Sullivan drove jeeps down to a portion of the route

that Lao- tian forces had managed to wrest temporarily from the Communists.

Even in the rainy season it was a thoroughly passable road that could

accommodate a 4×4 truck, but it was almost totally obscured from view by the

forest canopy and a meticulously constructed trellis. It was apparent that

fast-moving, high-flying jet reconnaissance aircraft were not up to the task.

On 10 December 1965 the CIA reported that the Communists had

expanded and improved their supply routes and that the NVA convoys now moved

almost exclusively at night. In the meantime, the air force and army launched a

joint operation. MACV Studies and Operation Group (MACVSOG) reconnaissance

teams made a shallow penetration of the Laotian border in search of NVA

supplies and trucks, while the air force stood by with strike aircraft. The

mission was successful and made more successful by a forward air controller (FAC)

who piloted a small, slow moving, observation aircraft and was able to identify

and mark additional targets for the strike aircraft. The success of the mission

led to a new operations plan, Tiger Hound, which would use FACs to locate and

mark the targets, and a C-130 airborne command-and-control center to direct

strike aircraft to the target. The area of operations was the eastern half of

the Laotian panhandle, an area that encompassed most, though not all, of the

infiltration routes, but avoided the more heavily populated western half, which

included Route 23, one of the principle infiltration routes.

The concept of using an FAC to locate and mark targets for

attack aircraft was not new. FAC organizations had evolved during World War II,

but were disbanded after the war only to be reinvented during the Korean War,

and again disbanded. Between the Korean War and Vietnam, the air force,

apparently believing that an FAC would be not needed in future conflicts,

directed its attention to development and procurement of high-performance jet

aircraft designed to penetrate Soviet air defenses and win the air superiority battle.

As a result, when the war in Vietnam started, the only aircraft available to

the air force that was capable of flying low and slow enough for pilots to

search for trucks on the concealed trails was the aging O-1

“Birddog,” a light- weight aircraft devoid of armor protection for

the crew and other crit- ical aircraft components. FACs were organized in

tactical air support squadrons (TASS), which were stationed through South

Vietnam. A covert organization of FACs calling themselves the Ravens was sta- tioned

in Laos. As President Kennedy had predicted in 1961, Raven pilots were

“civilianized”; that is, they were stripped of their military

identity and were flying unmarked aircraft. These slow-moving, propeller-driven

aircraft were precisely what was needed to seek out the hidden enemy supply

routes. Under ideal circumstances pilots selected for the forward air control

mission were experienced fighter pilots, well versed in air-to-ground attack.

But as the Vietnam War progressed, the demand for FACs increased to the point

that B-52 pilots from the Strategic Air Commander as well as transport pilots

were trained and assigned as FACs.

The 20th TASS, stationed in Da Nang, supported Operation

Tiger Hound. The squadron established a forward operating base at Khe Sanh in

northwest South Vietnam, adjacent to the Tiger Hound area of operations. One

month after its arrival it deployed Capt. Benn Witterman with a detachment of

six pilots, five aircraft, and thirteen support personnel from Da Nang Air Base

to the Royal Thai Air Force Base at Nakhom Phanom, Thailand, to conduct visual

reconnaissance on the Communist supply lines in the Laotian panhandle. Twelve

more pilots and ten additional aircraft arrived during the first week of April

1966. In addition to seeking out targets during the nights, the FACs flew

continuous daylight missions collecting all visible clues as to the location of

the multitude of roads, trails, and storage areas and slowly began mapping out

some of the infiltration routes. In June General Westmoreland reported that FAC

saturation of the Laotian panhandle was paying rich dividends as the FACs’

familiarity with the enemy’s logistical system and pattern of activity

increased.

Witterman’s detachment remained at Nakhom Phanom and was

designated the 23rd TASS flying under the call sign “Nail.” Nakhom

Pha- nom (nicknamed NKP and sometimes “naked fanny” by the American

pilots) was located eight miles west of the Mekong River, which formed the

boundary between Laos and Thailand. It was northwest of Tchepone and southwest

of the Mu Gia Pass on the Laos-North Vietnam border. Both of these major

infiltration sites were well within range.

The air force recognized the deficiencies of the O-1

aircraft and began the process of design and procurement for a replacement, the

OV-10. But because of the immediate need for an upgraded FAC aircraft, the air

force purchased an off-the-shelf aircraft, the Cessna “Super

Skymaster,” as an interim solution. The modified Skymaster, designated as

the O-2, was a twin-engine aircraft with the engines installed in line. The

front engine powered a “puller” propeller and the rear engine powered

the “pusher” propeller. The O-2 had greater mission time and airspeed

and was more heavily armed than the O-1. Although designed to be capable of

sustaining single-engine flight, the additional weight of armament and radios

combined with high-density altitude made it almost impossible to stay airborne

with a single engine. Walter Want, an FAC assigned to the 23rd TASS, wryly observed,

“if you lost an engine in the O-2, the second engine would get you to the

scene of the crash.”

In February 1967 the FACs were flying O-1 Birddogs and O-2s.

Daylight missions were flown single-pilot, without the benefit of a copilot.

Normally the trip to the objective area required about forty-five minutes to an

hour. After spending an hour reconnoitering and directing strike aircraft and

an hour return flight, there was about a thirty-minute fuel reserve left for

contingencies such as tactical emergencies and weather variations. The primary

navigation equipment was a magnetic compass and a map. When the pilot found a

target he contacted the airborne command-and-control center (ABCCC) and

requested strike aircraft. The ABCCC would issue a fragmentary (frag) order,

diverting strike aircraft to the target. Once the strike aircraft arrived, the

FAC provided the target description, location, and all known antiaircraft gun

locations to the strike aircraft and marked the target. Once the strike

aircraft identified the target, the FAC cleared the strike aircraft to hit the

target and stood by to conduct a post-strike bomb-damage assessment.

Night missions were flown in a blacked-out O-2 with a crew

of two pilots. One pilot flew while the other hung out the window searching for

targets with a starlight scope. The night missions were usually flown as

hunter-killer teams: the FAC was the hunter and the killer was usually an A-26

holding in an orbit a safe distance away. In order to maintain vertical separation

and avoid a mid-air collision, the blacked out O-2 had a shrouded red

navigation light installed on the top of the fuselage. The pilots marked

targets with rockets, flares, or phosphorus logs dropped from the wing stores.

The A-26 was a modified twin-engine World War II light

bomber, painted black for night operations and equipped with eight .50-caliber

machine guns in the nose, as well as wing-mounted guns and racks for bombs and

flares. An A-26 squadron with the call sign “Nimrod,” which had

covertly deployed to South Vietnam in 1961, arrived at NKP in 1966. The A-26

possessed awesome firepower, but as NVA air defenses improved, the vintage

aircraft proved vulnerable to ground fire. Like other World War II-era

aircraft, it was no longer in pro- duction and every loss was irreplaceable.

The remaining A-26s were withdrawn in 1969.

The OV-10 “Bronco” was the first aircraft designed

specifically as an FAC aircraft. As opposed to the O-1, which offered little

more ballistic protection than a Solo cup, the crew had armored seats, and the

aircraft was equipped with self-sealing fuel tanks. It was also much more

powerful and heavily armed. With the centerline fuel tank installed, the OV-10

had a range of 1,200 miles, over twice that of the O-1. The external stores

racks on the wings provided a wide selection of possible armaments

configurations, but with the centerline fuel tank installed, the most common

configuration was two seven-shot rocket pods, each loaded with smoke rockets,

and two M-60 machine guns. During the later years of the war, some OV-10s were

also equipped with laser designators to guide precision munitions.

Aircrews had to comply with a bewildering array of

constantly changing restrictions imposed by higher authorities to minimize the

risk of civilian casualties and to prevent widening the war. Rules of

engagement (ROE) agreed upon by CINCPAC, MACV, and the American embassy in

Laos, and further supplemented by restrictions ordered by the 7th Air Force,

stated what was permitted or forbidden during the air war over Laos. Laos was

divided up into seven sec- tors, and while there were rules that applied to all

sectors, some rules applied only to specific sectors. In the sectors delineated

as armed reconnaissance areas, U. S. aircraft could strike targets of

opportunity outside of a village provided it was within two hundred yards of a

motorable road or trail and the target had been validated by the Royal Laotian

Air Force, or in an alternative case, if approval was granted by an air attaché

and fire had been received from the target. In some areas air strikes were

prohibited unless an FAC was present. In other areas, air strikes could be

conducted, but only if the pilot could confirm his position using radar or a

tactical air navigation system (TACAN). Overflight of Laotian cities was

prohibited, and aircraft had to remain clear of some of these cities by as far

as twenty-five nautical miles. Such ROE were directive in nature, and

violations had serious con- sequences. Because the ROE changed periodically,

every pilot was responsible for keeping abreast of changes. All of these rules

were intended to prevent civilian casualties and accidental strikes against

friendly ground forces. The Communists understood these rules and used the

restrictions to their advantage.

Reports of a growing enemy supply capability followed every

report of progress in the war against trucks. Despite a tremendous number of

truck kills reported between 1966 and 1968, the CIA reported that the enemy’s

capability to infiltrate troops and supplies into the northern part of South

Vietnam would increase because of an intensive NVA effort to construct supply

routes with limited all- weather capability. During the wet season, the

throughput capacity of the roads leading into the A Shau Valley was estimated

to be only 15 percent lower than during the dry season. Such all-weather capabilities

would give the NVA the ability to increase deliveries by fifty tons per day.

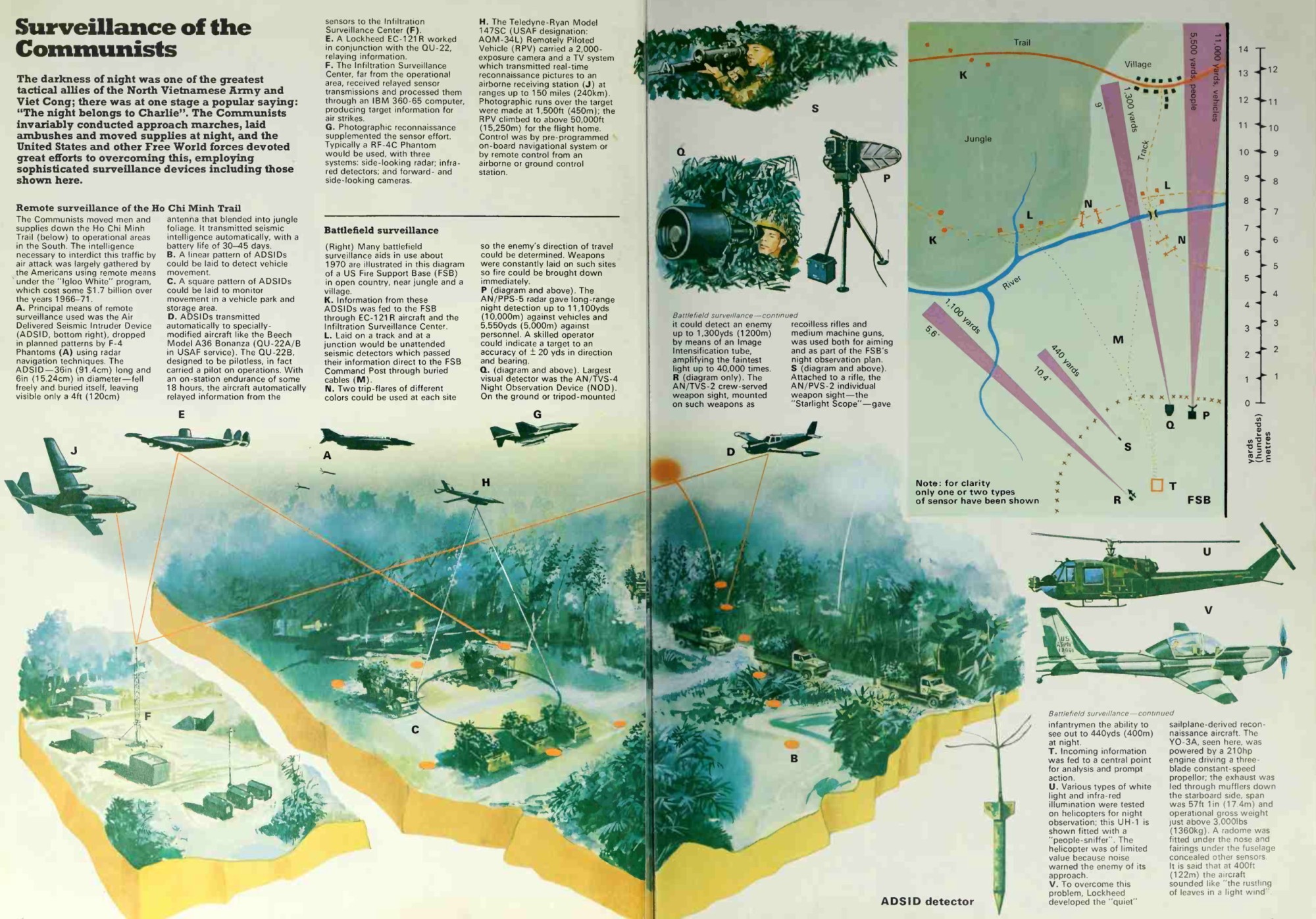

As the war progressed, so did American technological efforts

to find and destroy trucks concealed beneath the forest canopy. In addition to

the sensors from Operation Igloo White, U. S. forces also developed and

deployed starlight scopes, radar, infrared scopes (designed to detect the heat

of truck engines), low-light television systems, and a “Black Crow”

system (that could detect the electrical emissions of vehicle ignition

systems). But each of these systems had inherent limitations and could not

offset the NVA advantages of cover and concealment afforded by the terrain and

weather. In an attempt to increase the ratio of truck kills to sightings, the

U. S. Air Force utilized increasingly lethal weapons systems and munitions. The

most lethal of these was the fixed-wing gunship. The weapons were installed on

the port side of the aircraft. When a target was sighted, the pilot would bank

left and execute a pylon turn around the target. He could keep his weapons on

the target as long as he remained in the turn, making multiple circles if

necessary.

The first aircraft modified for this mission was the World

War II vintage C-47 armed with three 7.62mm mini-guns. Later, C-119s were

modified and 20mm Gatling guns were added to the arsenal. By the time the

AC-130 gunship was fielded, the armament included 40mm Bofors guns, and a

limited number of AC-130s were outfitted 105mm howitzers.

As the lethality of aerial weapons systems increased, so did

the lethality and numbers of NVA antiaircraft systems, and the large,

slow-moving gunships were forced away from critical areas of the trail. But

FACs controlling fighter-bombers remained. FACs also played a critical role in

the ground war on the infiltration routes as the communications outlet and the

guardian angels of the small, out- numbered, reconnaissance and road-watch

teams that existed to find targets for the air arm and collect intelligence.