First Partition of

Poland

Under the principles of eighteenth-century diplomacy,

Prussia and Austria wanted compensation. A gain for any great power, in this

case for Russia from Turkey, should be matched by gains for the other great

powers. In this case, there was a ready store of territory available for

compensation: Poland. Until the 1770s, both Russia and Prussia recognized the

benefits of a weak Polish buffer state. Despite the benefits of this

arrangement, some within Russia called for the outright annexation of Poland,

not merely the maintenance of a puppet. In 1764, Catherine engineered the

election of her former lover Stanislaw Poniatowski as the new Polish king, but

he proved surprisingly committed to Polish reform. The heavy-handed tactics of

Catherine’s agents in Poland provoked the creation of an anti-Russian

confederation in 1768 and ongoing rebellion against Russian domination. It was,

in fact, the spillover from this fighting that had triggered the ongoing

Russo-Turkish War.

Catherine’s entanglement in Poland while fighting the

draining Turkish war allowed Austria and Prussia to take advantage. Frederick

the Great proposed a mutually satisfactory outcome: Prussia, Austria, and

Russia would each take territory from Poland, punishing it for instability and

maintaining the European balance of power. All three parties were amenable, and

the Poles were forced to accept the loss of a substantial portion of their

country. Russia’s share, confirmed by treaty in 1772, brought in 35,000 square

miles along the frontier with Lithuania and 1.3 million Orthodox Belorussians.

In effect, Russian gains at Ottoman expense resulted in compensation for

Austria and Prussia at Poland’s expense.

While the partition was finalized, the Russo-Turkish War

dragged on. Rumiantsev briefly raided south across the Danube in June 1773. The

key significance of that year was the emergence of Aleksandr Vasil’evich

Suvorov as an aggressive and innovative commander, who later inherited

Rumiantsev’s place as Russia’s most talented field general. Repeating the

cross-Danube raid one year later, Rumiantsev’s advance guard under Suvorov

stumbled into Turkish troops near Kozludzha on 9/20 June 1774. Pursuing them through

dense, hilly terrain, Suvorov’s forces emerged into a direct confrontation with

the Turkish main force. Forming their accustomed squares, Suvorov’s troops

pushed forward slowly against the Turks, who broke and ran in the face of

Russian firepower and Suvorov’s direct assault.

Kozludzha was the final blow. The Ottomans requested a

cease-fire, and the peace treaty was signed at Kuchuk Kainardzhi a month later.

Frederick the Great was unimpressed with the Russian victory, dismissing it as

“one-eyed men who have given blind men a thorough beating.” This is

mistaken on two counts. First, it ignored the scale of Russian gains. In

addition to freedom of transit for Russian trade, Catherine won a portion of

the northern coast of the Black Sea, leaving the Turks Moldavia, Wallachia, and

Bessarabia. The Crimea received nominal independence under Russian hegemony.

The Ottoman sultan was forced to protect his Orthodox Christian subjects, a

clause that gave future tsars a ready issue to exploit, while the Ottomans retained

protective rights over the religion of the Crimean Tatars. Catherine now

controlled the Dnepr to its mouth, though the river’s rapids disappointed her

hopes for exports. Second, the Russian army had shown an impressive capacity to

fight battles and campaigns at a great distance from its bases, while

displaying tactical ingenuity and flexibility that clearly pointed toward the

developments Napoleon later employed so effectively.

Portrait of Russian Field-marshal Grigorii Potemkin (1739-1791)

The Russo-Turkish

War, 1787-1792

The end of the first Turkish War marked the emergence of

Grigorii Potemkin, able cavalry commander, as a central figure in Catherine’s

life, and through that, in the Russian army and government. Among Catherine’s

many lovers, none matched Potemkin’s political influence, and only Potemkin was

Catherine’s equal in intellect and force of personality. They may have secretly

married, and even after their affair cooled Potemkin remained Catherine’s most

important advisor until his death. Potemkin became through Catherine’s favor

first a vice-president of the War College and then its president from 1784. He

also served as governor-general of Catherine’s newly acquired Ukrainian

territories.

Though charismatic and intelligent, Potemkin had little

patience for discipline or orderly procedures. His experience under Rumiantsev

fighting the Turks made him a committed advocate of speed and initiative, not

careful staff work. Catherine’s military administration suffered as a result,

particularly the development of a general staff. As a favorite of Catherine’s,

he in turn promoted favoritism within the War College. At the same time, he

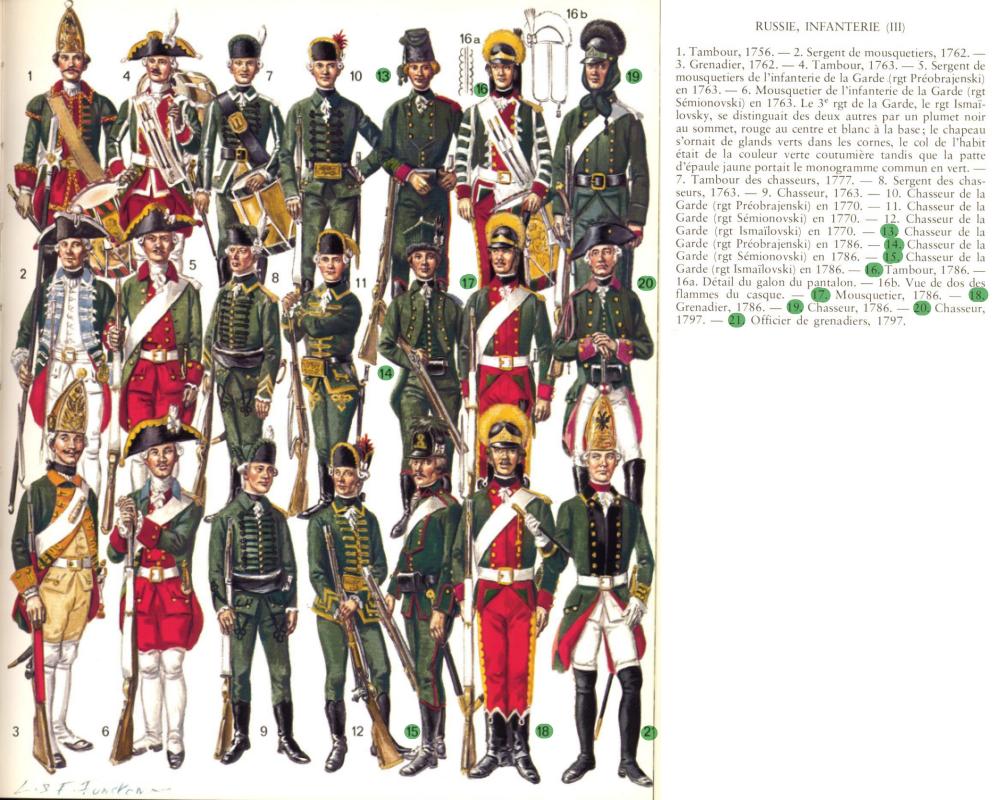

showed genuine concern for his troops and their needs. He simplified the

uniforms of the Russian infantry, keeping the traditional Russian green but

removing the decorative flourishes that hindered speedy action. He deemphasized

heavy cavalry as inappropriate for Russia’s military tasks and controlled and

disciplined the useful but rambunctious cossacks of the frontier.

Catherine’s territorial expansion continued over the next

decade, though she avoided entanglement in the wars of western and central

Europe. Turbulent Crimean politics led Catherine to intervene in 1776 to restore

Russian domination. Russia was nearly pulled into the Anglo- French conflict

surrounding the American war for independence, and in 1780 Catherine engineered

the League of Armed Neutrality with Denmark and Sweden to protect neutral

shipping from British interference. Catherine also dreamt vaguely of Russian

satellite states in Greece and the Black Sea Straits, naming her grandson

Constantine in a nod to his future throne in Constantinople. Pursuing that goal

required better relations with Austria in the Balkans, and Catherine

established an alliance with Austria in 1781. It also necessitated naval power

in the Black Sea, and Catherine accordingly expanded and modernized the Russian

flotilla in the Sea of Azov, and at the newly established city of Kherson at

the mouth of the Dnepr. Under the able leadership of Fyodor Fyodorovich

Ushakov, this became the Black Sea Fleet. Faced with a joint Austrian and

Russian threat, the Ottoman Turks unhappily accepted Catherine’s 1783 full

annexation of the Crimea. In the same year, she established a protectorate over

the kingdom of Georgia. Russia built a military highway through the Caucasus

Mountains to link Georgia with Russian territory and stationed troops in its

capital Tbilisi. Russia’s rapid development of its newly acquired Ukrainian

territory, its Crimean annexation, its infractions of Ottoman honor, and

Catherine’s triumphant tour of her conquered southern territories finally led

the Turks to declare war in August 1787.

The second Russo-Turkish War of Catherine’s reign opened

poorly. Catherine was unable to take the war to Turkish territory, fearing an

amphibious invasion of the Crimea. Suvorov, hero of the first Turkish war, ably

defended the seaside fortress of Kinburn, on the Dnepr estuary, against two

Turkish amphibious assaults in September and October of 1787, but Russia’s

Black Sea Fleet was badly damaged in a storm. An attempt to transfer ships from

Russia’s northern waters was prevented by diplomatic complications. Though

Austria joined Russia’s war in early 1788, its dismal performance provided

little concrete assistance. Sweden attacked Russia in summer 1788 with covert

British and Prussian support, forcing Catherine to keep her ships in the Baltic

for the defense of Petersburg. The Swedish war was more nuisance than threat,

made dangerous only by the larger war against the Turks and the possibility of

Anglo- Prussian intervention. While the Russian and Swedish fleets clashed

repeatedly in the Baltic, Catherine stirred up antiroyal opposition within

Sweden itself and achieved brief Danish intervention against Sweden.

Only in 1788 was Catherine able to bring her real advantage

to bear against the Turks: a large and disciplined army. As in the previous

war, Catherine split her forces in two west of the Black Sea. Rumiantsev, the

most successful commander of 1768-1774, was forced to settle for a small

auxiliary force of 40,000 well inland of the Black Sea to protect the right

flank of the main army. That army of nearly 100,000 under Potemkin was tasked

with the recurring problem of war against the Turks: capturing the many large

and tenaciously defended fortresses studding the river barriers between Russia

and the Turkish capital. Though Potemkin had great hopes, his push south

stalled at its first obstacle: Ochakov and its garrison of 20,000. Though a

naval campaign enabled Potemkin to cut Ochakov off from the sea, his poorly

handled six-month siege achieved nothing. Desperate to take the fortress before

the end of the year, Potemkin unleashed a costly but successful all-out storm

on 6/17 December 1788. Since Potemkin’s position was inviolable, Rumiantsev was

sacrificed for the debacle-recalled from his command and retired from service.

For 1789, the Russian plan was to concentrate on capturing

Turkish fortresses guarding the Dnestr River: Akkerman at its mouth on the

Black Sea and Bender almost 100 miles upstream. To distract the Turks and

provide a link to Russia’s Austrian allies, a corps under Suvorov moved far

south, past the Dnestr and Prut into Moldavia and Wallachia (presentday

Romania). At the request of his Austrian allies, threatened by a much larger Turkish

force, Suvorov led a forced march to unite the small allied detachments.

Greatly outnumbered, Suvorov nonetheless went on the attack, using battalion

squares similar to those Rumiantsev developed to attack a fortified Turkish

encampment at Fokshani (eastern Romania) on 21 July/1 August 1789. Cooperating

with the Austrians to attack from two directions, Suvorov sent 30,000 Turkish

troops into panicked flight after a day-long struggle for the encampment.

Suvorov repeated his feat at Rymnik in September. Once

again, superior Turkish forces attempted to catch an isolated Austrian

detachment alone. Responding to pleas for aid, Suvorov rushed to create a

combined army of 25,000 soldiers against 100,000 Turks. Suvorov’s insistence on

attack and decisive action led him to assault the Turkish army while it was

encamped, counting on speed and audacity to defeat the enemy army in detail,

destroying its individual parts before they could unite. The Turks were in

three fortified encampments too far apart for mutual support in a line

stretching west to east between the Rymna and Rymnik rivers. On the morning of

11/22 September 1789, the Russo-Austrian force crossed the Rymna River north of

the Turkish camps, deploying into battalion squares in a checkerboard pattern.

Suvorov’s troops moved south alongside the Rymna to attack the westernmost

Turkish camp, while the Austrians pushed southeast against the central one.

Undeterred by a Turkish cavalry attack, Suvorov easily captured the western

camp and sent its troops fleeing in disorder. He then turned east toward the

central camp, clearing a small forest en route and eliminating a Turkish

counterattack that had wedged itself between Suvorov and the Austrians to his

northeast. He then joined the Austrian attack on the central camp. As his

advance unhinged the left flank of the Turkish defense, Suvorov noticed the

poorly constructed and incomplete fortifications of the camp and, in a

violation of military orthodoxy, sent his cavalry to storm the position,

followed by a bayonet charge. The broken Turkish troops fleeing east carried

panic with them, and the allied forces captured the third, easternmost camp by

the end of the day. A full day’s fighting had inflicted nearly 20,000 casualties

on the Turks at the cost of fewer than 1,000 from the allies.

Those two victories gained Suvorov both symbolic and

financial rewards from Catherine and boosted his repute even further in the

Russian army. From a military family, Suvorov was gaunt and eccentric, almost

manic, but passionately loved by his soldiers. Following Rumiantsev’s model, he

emphasized the importance of hard and realistic training in peacetime, and

speed, decisiveness, and shock in battle. Fighting the brave but fragile

Ottoman army, these qualities of discipline and ruthlessness served him well.

“The bullet’s a fool,” he remarked, “but the bayonet’s a good

lad.”

The Russian main army was less audacious than Suvorov in

1789, but nevertheless won important successes. That autumn, the Dnestr River

fortresses of Akkerman and Bender both surrendered, giving Russia control of

the length of the river. Austria captured Belgrade and Bucharest, and the

Ottoman hold on the Balkans seemed broken beyond repair.

In fact, Catherine’s diplomatic position was growing

increasingly precarious. In addition to the usual expenses in lives and money,

Catherine faced a draining naval war with Sweden, and, worse, the prospect of

war against a British-Prussian alliance, eager to limit Russian power, gain new

sources of naval stores, and eliminate Russian influence from Poland. In early

1790, Catherine’s ally Joseph II of Austria died, and his successor Francis II

moved quickly to make peace. The strain began to ease in August 1790 when an

exhausted Sweden agreed to end its war with Russia, but a

British-Prussian-Polish attack against Russia was still possible. Frederick the

Great had cheerfully proposed the partition of Poland, but his successor

Frederick William II now affected sympathy for Polish concerns and support for

Polish reforms.

The danger of general war and fear of a Turkish invasion of

the Crimea delayed serious campaigning in 1790, and the only Russian effort

that year was the siege of the Turkish fortress of Izmail, capture of which

would give Russia a vital foothold on the Danube River. In late 1790, 35,000

Russian troops arrived outside Izmail. The brief campaigning season and the

30,000-strong Turkish garrison made the Russian commanders despair of capturing

the fortress until Suvorov arrived and insisted on taking it immediately.

Feigning preparations for a lengthy siege while secretly training his soldiers

for assault, Suvorov launched a general storm on Izmail before dawn on 11/22

December 1790. This captured three gates, allowing the Russians inside the

walls. Desperate house-to-house Turkish resistance continued the rest of the

day, with the Russians hauling artillery in for point-blank fire against

Turkish strongpoints. In the day’s slaughter, two-thirds of the Turkish

garrison was killed, and the rest captured.

The Turkish ability to resist was dwindling, but the

prospect of foreign assistance kept the Ottomans in the war. Prussia and

Britain insisted on the return of Russia’s conquests, culminating in a March

1791 ultimatum to Russia to end the war on Turkish terms. Catherine stood her

ground, and it became clear that the British government had badly overestimated

its public’s appetite for war. Catherine’s ambassador to Britain helped with a

masterful public relations campaign. And without British backing, Prussia had

no appetite for a fight. Prussia began exploring other options: compensating

for Russia’s gains at the expense of Poland once again. Poland itself made

matters much worse in spring 1791. Believing in Prussian protection, and

inspired by the French Revolution, Poland established a new, centralized

constitution. Once the Turkish war was over, Catherine could never allow Poland

to build a functional government.

With growing urgency to end the war, Russian campaigns in

1791 extended south of the Danube. After a series of successful smaller

engagements, Russian commander Nikolai Vasil’evich Repnin won the final major

battle of the war at Machin. After a Danube crossing and a forced march through

swamps, his 30,000 troops attacked a fortified Turkish encampment on 28 June/9

July 1791. The plan-to fix the Turks with a frontal attack while the main

Russian forces circled left to make a decisive flanking blow-fell apart.

Abandoning the passivity that too often characterized their fighting against

the Russians, the Turks detected the Russian flanking maneuver and launched

repeated counterattacks against it. Once again, Russian firepower and

unbreakable squares repulsed the attacks, and the Turkish defense finally fell

apart. Machin forced the Turks to accept defeat. A preliminary peace was

reached immediately, and a final peace on 29 December 1791/9 January 1792,

giving Catherine possession of the territory between the Bug and the Dnestr

rivers, but returning to the Ottoman Empire many of the fortresses and much of

the territory it had lost.

Catherine’s former lover, possible husband, and chief

political confidant Potemkin had died while negotiating with the Turks. Despite

this, Catherine’s room to maneuver had grown substantially, freed from war with

Turkey and Sweden. In spring 1792, Prussia and Austria became embroiled in war

with revolutionary France, giving Catherine the opening she needed to smash the

Polish reforms. Using an invitation from pro-Russian Poles as political cover,

Catherine’s armies intervened in May 1792 to restore Poland’s previous

constitution. Though Poland’s hastily assembled forces managed some initial

victories, Russia’s preponderant strength meant that Poland’s position was

hopeless. Poland’s King Poniatowski lost his nerve and called off all

resistance.

Catherine used her overwhelmingly dominant position to claim

compensation from Poland for her efforts to crush revolution. Frederick

William, with his war against revolutionary France going badly, comforted

himself with Polish territory. By January 1793, Russia and Prussia had agreed

on their territorial seizures. This second partition of Poland netted Russia

the Lithuanian half of the Polish kingdom and right-bank Ukraine, almost

100,000 square miles of territory and 3 million new subjects. Poland itself was

reduced to a vestigial and clearly nonviable fragment of its former territory.

What was left of Poland could not survive, giving Poles

nothing to lose. Widespread passive resistance became open rebellion in spring

1794. Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who had assisted the American war for independence

against Britain, became leader of the Polish national movement. This uprising

seized control of Warsaw and even defeated initial Russian attempts to quash

resistance. Overwhelming force, this time brought to bear by all three of

Poland’s great power neighbors, again meant that Poland’s freedom was only

temporary. Rumiantsev commanded the general suppression of the uprising, while

Suvorov with his fearsome reputation was brought in to subdue Warsaw.

Kosciuszko was wounded in battle and captured, and then on 24 October/4

November 1794, Suvorov stormed Praga, a suburb of Warsaw across the Vistula

River. In full view of Warsaw’s horrified citizens, Suvorov’s troops massacred

thousands, soldiers and civilians alike. Warsaw surrendered without a fight.

Early in this uprising, Catherine had become convinced the time had come for

the complete partition of Poland. Austria, Russia, and Prussia agreed on a

settlement, the third and final partition, that ended Poland’s existence as an

independent state for over a century.

Throughout Russia’s history, it has enjoyed an advantage in

size and population over its rivals. Under Catherine, that advantage was

applied more effectively than perhaps at any other time in Russia’s history.

The mechanisms of Catherine’s absolutist state turned resources into practical power,

power that eliminated Poland from the map of Europe and ended any hope that the

Ottoman Empire might compete on equal terms with Russia. During Catherine’s

lifetime, though, Russian superiority was already being undermined. The French

Revolution introduced new principles of government, principles that translated

into new sources of military power. The French revolutionary governments, and

the Napoleonic Empire that followed them, turned those new principles into mass

armies driven by French nationalism and revolutionary fervor, armies that

Russia would be hard-pressed to match.