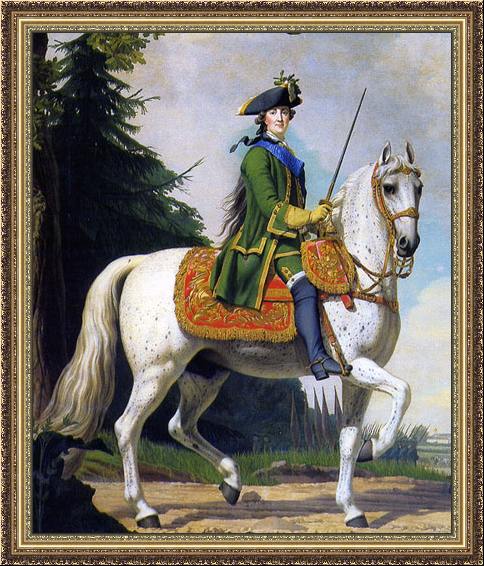

Equestrian portrait of Catherine in the Preobrazhensky Regiment‘s uniform, by Vigilius Eriksen

Catherine the Great ruled Russia for the final third of the

eighteenth century. She earned her sobriquet “the Great” through

relentless and successful territorial aggrandizement. Her career perfectly

illustrates the opportunities and costs of foreign policy in an era of amoral

balance-of-power politics. Contrary to theories that suggest balance-of-power

politics produce stability, the eighteenth century in fact displays a ruthless

and relentless struggle for military advantage and territorial expansion, with

the only alternative decline and destruction. In that arena, Catherine employed

Russia’s immense human resources well. Her reign demonstrated a mastery of

effective and rational absolute rule. She took advantage of the increasing

sophistication of Russia’s administrative machinery to extract resources and

turn them efficiently to achieve foreign policy ends. Her power, and Russia’s

power, were based on serfdom, but that was no hindrance. Before the Industrial

Revolution, a servile labor force and an army drawn from unwilling and

illiterate serfs was no handicap. Indeed, under Catherine Russia suffered fewer

military consequences from its economic and social gap with western Europe than

at any time in its history. Catherine suffered, during her lifetime and after,

from lurid allegations about her notoriously immoral and disordered personal

life. In fact, her personal life was quite ordered: temporary but passionate

monogamous relationships with a series of court favorites. In that sense, she

was as restrained as most European monarchs and more upright than many. Her

personal conduct was noteworthy only because she was a woman. Had she been a

man, no one would have noticed or cared. The true amorality (not immorality) of

Catherine’s life was her conduct of foreign policy. She played the game by the

rules of her time and played it very well.

Peter III ruled Russia only six months. He fell to a coup organized by and on behalf of his wife Catherine, with whom he shared only mutual detestation. Pregnant with another man’s child when Peter took the throne, Catherine knew herself to be extremely vulnerable. Peter’s German sympathies and withdrawal from the Seven Years’ War were highly unpopular with segments of the Russian elite, as was his confiscation of vast land holdings from the Orthodox Church. He moved Russia toward war with Denmark not in defense of Russian interests, but those of his ancestral home Holstein. Though Catherine later attempted to paint her husband as unstable, even insane, the contemporary evidence is more complex. All this was not itself enough to bring a coup. That required Catherine’s active intervention in the personal and factional politics at court. Catherine relied above all on contacts and friends among the officers of the guard’s regiments, with whom she seized power in St. Petersburg on 28 June/8 July 1762 before Peter, outside the city, even knew what was happening. After a brief attempt to flee, Peter meekly surrendered. Catherine’s co-conspirators then murdered him.

Peter’s brief reign produced a major change in the status of

the Russian nobility, all of whom in principle were lifelong servants of the

state, generally as military officers. In 1736, Tsar Anna Ivanovna had granted

the right to retire after 25 years in service and had allowed noble families to

keep one son home as estate manager. All tsars had in practice granted lengthy

leaves to allow nobles to tend to their estates and families. Peter III went

beyond that. On 18 February/1 March 1762, his emancipation of the nobility

granted a host of rights that had before only been gifts of the tsar. No noble

was obliged to serve, and nobles in service could generally retire whenever

they wished. Peter’s goals were professionalizing the officer corps and

improving estate management and local government through the greater physical

presence of the nobility in the countryside. His emancipation ably served those

goals and lasted much longer than Peter himself. As military service still

brought prestige and social advancement, large numbers of nobles continued to

serve, while the Russian army supplemented them as before with foreign professionals.

Peter’s action was immensely popular among the nobility; the Senate voted to

erect a golden statue in his honor.

Despite Catherine’s systematic effort to blacken her late

husband’s name and character, she reversed none of his policies. She kept the

lucrative church lands he confiscated, kept noble military service optional,

and formally confirmed this right in her own Charter of the Nobility in 1785.

Moreover, Catherine was in no hurry to bring Russia back into the Seven Years’

War. The war’s expense and her empty treasury led Catherine to embark on

conservative consolidation. Catherine gracefully and delicately solidified her

position on the throne while repairing the worst damage done by Peter’s

arbitrary foreign policies.

Catherine retained oversight of foreign affairs, but gave

its management to Nikita Ivanovich Panin. Panin’s foreign policy in the early

years of Catherine’s reign was a “northern system.” This alliance

with Prussia and Denmark was intended to counter the French-Austrian alliance

in southern Europe, influence events in Poland, and prevent any attack by

Sweden. Centered around a 1764 alliance with Prussia, Panin’s system functioned

rather well. It protected Prussia against war with Austria, while providing

both countries valuable time to recover from the Seven Years’ War. The system’s

chief weakness, aside from British hostility, was the paradoxical nature of

Catherine’s interests in Poland. On the one hand, as Russian tsars before her,

she wanted a stable and weak Polish buffer state, a view shared by her new ally

Frederick the Great. A number of Polish elites, however, recognized how

vulnerable Poland’s weak central government made it and jockeyed to rewrite the

Polish constitution to make Poland stronger and more capable. The harder

Catherine worked to prevent constitutional reform in Poland and plant a

reliably pro-Russian candidate on the Polish throne-through bribery,

intimidation, and military intervention-the more she generated Polish

resentment and efforts to eliminate Russian influence entirely.

The Russo-Turkish

War, 1768-1774

The turmoil generated by Catherine’s meddling in Poland led

to her first war, against the Ottoman Turks. An internal Polish dispute about

the rights of Protestants and Orthodox in that predominantly Catholic country

exploded into violence in volatile right-bank Ukraine. The combination of a

Russian troop presence in Poland, the spillover of violence by Orthodox

Cossacks into Crimean and Ottoman territory, and substantial support from

France led the Ottoman Turks to demand full evacuation of Russian troops from

Poland in October 1768. When Russia refused, the Turks declared war.

Catherine took an active and personal interest in the war,

unlike her predecessors. She made a priority of territorial expansion; though

the Turks started the war, the security and economic development of southern

Russia depended on finishing it on Russian terms. Catherine was central to the

war’s strategy and decision making, consulting regularly with key military and

political advisors. Though Russia’s intervention in Poland left few troops for

active operations in 1768, Russia was fundamentally in good shape for war. Army

strength was roughly equivalent to that available to Peter the Great at his

death in 1725: 200,000 regulars, plus irregular, militia, and Cossack units.

Catherine expanded this by additional conscription from peasant households for

lifetime service in the army. Despite Russia’s immense armed forces,

maintaining troops in the distant theaters of the Turkish wars required

repeated and painful levies of new peasant soldiers. Long marches through the

war-ravaged and desolate territories of western Ukraine and the Balkans meant

that a substantial proportion of any Russian army was lost well before reaching

the theater of war.

The Russian and Turkish armies were both in the midst of

long and difficult reforms to bring themselves up to modern standards. As the

war’s campaigns demonstrated, the Russians were much further along. Enormous

Turkish forces, greatly outnumbering their Russian opponents, were brittle and

undisciplined, unable to sustain heavy combat. Part of this had to do with the

high proportion of cavalry in Turkish armies, making flight from battle too

easy while hindering positional defense. Furthermore, much of the Turkish

cavalry consisted of a feudal levy, something the Russians had been gradually

abandoning for over a century. The Russian officer corps had been hardened by

the Seven Years’ War against the best army in Europe; the Turks were no match.

Count Pyotr Alexandrovich Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky

In particular, Peter Rumiantsev, Catherine’s most successful

commander, was highly innovative and adaptable. In the wake of the Seven Years’

War, the Russian army had dramatically expanded its jäger light infantry, which

Rumiantsev used to counter the maneuverable Tatar cavalry. He also emphasized

discipline, organization, and shock, particularly night and bayonet attacks, to

take advantage of poorly managed Turkish troops. His specific tactical

innovation was the use of divisional squares in both defense and attack. These

hollow squares, each consisting of several regiments of infantry and studded

with field artillery, were used for both defense and attack. Their all-around

defense protected them from circling multitudes of Turkish and Tatar cavalry,

but allowed sufficient firepower and shock for attack. The firepower lost in

forming squares as opposed to lines was a price worth paying against the Turks,

though it would have been suicide against a Western army. In battle,

Rumiantsev’s squares maintained open space between them to allow for

maneuverability, while remaining close enough for mutual support. The gaps

between squares were covered by cavalry or light infantry, which could if

necessary take refuge inside the larger divisional squares. Given the brittle

and relatively undisciplined Turkish troops, Rumiantsev disdained heavy cavalry

as unwieldy, trusting instead in firepower and infantry attacks to break enemy

will. Strategically, Rumiantsev avoided the crippling loss of time and

resources involved in annual treks from winter quarters to the front by maintaining

his forces as far forward as possible year-round.

Initial Russian operations in 1769 were extremely

successful, so successful that Russian forces found themselves overextended.

Over the course of 1769, a Russian army, under first Aleksandr Mikhailovich

Golitsyn and then Rumiantsev, who replaced Golitsyn that autumn, swept south in

a wide arc around the western edge of the Black Sea, crossing the series of

rivers that ran into it: the Bug, the Dnestr, and the Prut. This left intact a

series of major Turkish fortresses along the Black Sea coast: Ochakov,

Akkerman, Izmail, and especially Bender on the Dnestr River. Failing to screen

or reduce those fortresses left Russian armies vulnerable to being cut off deep

in Turkish territory. As a result, Catherine’s government devised a new plan of

campaign for 1770. The two Russian armies were to move in parallel, with

Rumiantsev’s First Army moving slowly south farther inland, while the Second

Army (led by Nikita Panin’s younger brother Peter) concentrated on clearing

Turkish fortresses along the Black Sea coast.

Outnumbered by the Turks, Rumiantsev moved quickly to defeat

separate Turkish contingents before they could unite into an overwhelming

force. Russian aggressiveness also prevented the Turks from taking advantage of

their superior manpower. Confident in the organization and discipline of his

troops, Rumiantsev used rapid and night maneuvers to catch the Turks unawares.

Rumiantsev’s tactics during this campaign, particularly his use of squares and clever

employment of flanking attacks, were inspired. Rumiantsev’s 40,000 troops

caught a Turkish army of 75,000 at Riabaia Mogila on 17/28 June 1770. Despite

being outnumbered nearly two to one by Turkish troops in a strong position,

Rumiantsev coordinated a multipronged attack. He led the bulk of Russian forces

himself in a frontal assault, while a smaller detachment under Grigorii

Aleksandrovich Potemkin crossed the Prut River shielding the Turkish left flank

to place itself across the Turkish line of retreat. At the same time, a

stronger detachment, including most of the Russian cavalry, attacked the

Turkish right. Confronted by Russian firepower and attacked from three

directions, the Turkish position dissolved into disordered flight. Rumiantsev

maintained his aggressive tempo, moving down the Prut and catching a second

Ottoman army where the Larga River flows into it. Behind the Larga 80,000

Turkish and Tatar soldiers were dug in. Using the cover of darkness, Rumiantsev

crossed the Larga upstream with most of his forces to launch a surprise attack

on the Turkish right flank. As the Turks shifted troops to their right, a

smaller detachment Rumiantsev had left behind pushed directly across the Larga

River, seizing the heart of the Turkish position. The Turkish army

disintegrated in confusion. In both battles, Rumiantsev was so successful that

he inflicted very few casualties on the Turkish forces. They broke and ran

before Russian firepower could inflict significant damage.

While Panin’s army besieged Bender, Rumiantsev met the

Turkish main forces on the Kagul (Kartal) River, north of the Danube River, on

21 July/ 1 August 1770. With only 40,000 troops to the Turkish grand vizier’s

150,000, Rumiantsev continued his offensive tactics, hoping to beat the Turkish

main forces before the arrival of additional Tatar cavalry. Launching a frontal

attack on the Turkish camp early in the morning, Rumiantsev’s strengthened

right wing drove back the Turkish left, but a counterattack by the Turks’

fearsome janissary infantry smashed the center of the Russian line and

temporarily tore a wide hole into the Russian formation. Rumiantsev himself

joined the reserves hastily thrown in to plug the gap. Once the janissaries had

been blasted into oblivion by Russian firepower, the rest of the Turkish army

again broke and fled, leaving supplies and artillery behind them. Rumiantsev

detached forces for an energetic pursuit, which caught the fleeing Turks at the

Danube. Only a tiny fraction escaped to safety on the far side. From this point,

the Turks were forced to remain entirely on the defensive, hoping for outside

intervention to rescue them from the war they started.

The Turkish catastrophe was not finished. The Ottoman

fortresses along the Black Sea fell rapidly into Russian hands after the Kagul

victory: Izmail, Akkerman, and Bender. To make matters worse, Catherine’s lover

Grigorii Orlov hatched an ambitious plan to bring a Russian fleet into the

Mediterranean to attack the Turks from the south. This meant repairing and

rebuilding the Russian fleet, dilapidated from decades of neglect, but

Catherine threw immense financial and diplomatic resources into the project.

When the Russian fleet arrived in Turkish waters in spring 1770, it attempted

unsuccessfully to stir Greece into rebellion against Turkish rule. It finally

brought the Turkish Aegean fleet to battle on 24 June/5 July 1770 at the fort

of Chesme off the Anatolian coast. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the

Russians’ attack threw the Turkish ships into confusion and disarray, and the

Turks withdrew into Chesme harbor. A night raid into the harbor with fireboats

torched the Turkish fleet, destroying it completely.

The overwhelming successes of 1770 were followed by a

historic triumph in 1771. Rumiantsev’s First Army consolidated its position and

continued to capture Turkish fortresses, but did not push decisively south

across the Danube. Instead, the Russian Second Army, now commanded by Vasilii

Mikhailovich Dolgorukii, pushed into the Crimea in June 1771 against scattered

resistance and conquered it, a feat that had escaped every previous Russian

army. Catherine set up a puppet khan and a treaty granting the Crimea formal

independence, but committing it to eternal friendship and permitting Russian

garrisons. Instead of a base for raids on southern Russia, the Crimea had

become a de facto Russian possession.

Despite Catherine’s staggering run of successes, she was

increasingly anxious for peace. Even victories were costly. Bubonic plague

raged west of the Black Sea and even in Russia itself, where it killed hundreds

of thousands. The conscription and taxes to maintain her army were increasingly

unpopular. In addition, Austria and Prussia submerged their differences in

common alarm over the extent of Russian victories and were eager to limit

Russia’s gains. The Ottomans asked for Austrian and Prussian mediation in 1770;

both governments moved with alacrity to assist, but peace negotiations went

nowhere. Though Catherine wanted peace, she would not settle for less than her

battlefield successes had earned.