Argentinian Invasion of the Falklands

Military operations have changed greatly since the end of

the Second World War, most of all because the development of nuclear weapons

has effectively prevented the major states from fighting the sort of full-scale

struggles for decision which are the subject of this book. Big wars are now too

dangerous for big countries to fight. That does not mean that the world has

become a safer place for the common man. On the contrary. It is estimated that

armed conflict since 1945 has killed fifty million people, as many as died in

the Second World War. Most of the victims, however, have perished in

small-scale, random struggles, many scarcely to be dignified even by the name

of civil war. In the last fifty years it is not the methods or weapons of

1939—45 that have harvested the major proportion of violent deaths – aerial

bombardment or battles between great tank armies or the relentless grind of

infantry attrition – but skirmish and all too often massacre with cheap small

arms.

Even in such few major wars as have been fought, there have

been few large-scale conventional battles and their number has tended to

decline over time. Thus, while the Korean war of 1950–3 was almost exclusively

a conflict of infantry and tank armies, and the Arab–Israeli wars of 1956–73

likewise, the biggest war of all, in Vietnam, was a protracted

counter-insurgency struggle, marked by the clash of armies scarcely at all.

Though the Iran–Iraq war of 1980–8 saw much heavy fighting, Iran’s lack of

heavy equipment and use of under age conscripts in suicide attacks made it an

unequal contest bearing little resemblance to other wars of the twentieth

century. In 1991 Iraq was forced to abandon its illegal occupation of Kuwait as

a result of defeat in one major tank battle; but its army, more concerned to

surrender than to stand its ground, cannot really be said to have given battle

at all. The same can be said of its performance in the 2nd Gulf War of 2003, in

which intelligence played an important role in the targeting early on of the

Iraq leadership.

That episode apart, the post-war military record yields few

examples of outcomes being influenced by operational intelligence of the sort

assessed in the previous chapters. Intelligence services have never been busier

than they are in the nuclear world and consume more money than has ever before

been spent. By far the greater proportion both of effort and funds is devoted,

however, to early warning and to listening, continuous processes, intended to

sustain security, not to achieve success in specific or short-term

circumstances. The elaborate infrastructure of early warning – radar stations,

underwater sensors, space satellite systems, radio interception towers – is

enormously expensive to build, maintain and operate and so are its mobile

auxiliaries, particularly airborne surveillance squadrons. The intelligence

material thus collected, categorised by professionals as sigint (signals

intelligence), overlapping with comint (communications intelligence) and elint

(electronic intelligence), requires processing and interpretation by thousands

of analysts and computer technicians. What they do and what they achieve is

rarely published. The public anyhow seems indifferent to what is unquestionably

the most significant sector of contemporary intelligence activity.

Understandably, the complexities of intelligence technique must baffle even

highly educated laymen. Only the most specialist of experts can hope to

comprehend what intelligence agencies now do. It is possible, with application,

for the interested general reader to follow descriptions of how the Enigma

machine worked and of how the problems it presented to cryptanalysts were

overcome. Modern ciphers, created through the application of enormous prime

numbers to language, belong in the realm of the highest mathematics and are

alleged to defy attack even by the most powerful computers yet built.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the intelligence world

attracts attention only when there is a breach of security, typically in recent

years by the ‘defection in place’ of an intelligence operative who yields to

greed or lust or exhibits defects of character not identified at the time of

recruitment. There has been a steady trickle of such scandals, long post-dating

the sensational unmasking of the ‘Cambridge’ spies in Britain and affecting the

American and Soviet services which were presumed to have been warned against

such occurrences in their own ranks by the ‘Third’ and ‘Fifth’ Man episodes.

Public interest is also engaged by accounts of the effect of

human intelligence, humint, on recent or current military operations, where

such effect can be shown. Humint has unquestionably played a major part in

Israel’s successful efforts to hold at bay its Arab neighbours in four major

wars, much minor conflict and its continuous struggle for security, for the

ingathering of Jews from neighbouring lands allowed its intelligence services

to recruit patriotic operatives who spoke Arabic bilingually and were able to

pass as natives in their countries of former residence. It is understandable

that the successes of Israeli humint remain almost completely secret. During

the Vietnam War the American CIA conducted a large-scale campaign of

destabilisation against the Viet Cong, largely by the targeted assassination of

Viet Cong leaders in the South Vietnamese villages. Operation Phoenix remains

unacknowledged; the Vietnam War was eventually lost; it would nevertheless be

illuminating to know what effect Phoenix had on its conduct.

The only conventional military conflict of recent times for

which a reasonably complete picture of the influence of intelligence on

operations is available in all or most of its complexity – signit, elint,

comint, humint and photographic or imaging intelligence – is the Falklands War

of 1982, between Britain and Argentina. Rights of sovereignty over the Atlantic

islands of the Falklands or Malvinas, which include such Antarctic outliers as

South Georgia, Graham Land and the South Shetland, Orkney and Sandwich groups,

has been disputed between Britain and Argentina since the nineteenth century.

The small Falklands population is exclusively British (the other territories

are effectively uninhabited) but it is a universal and deeply held belief in

Argentina that the lands are theirs. Argentina has a troubled political

history. Once a country of great wealth, which attracted to it over the last

century large numbers of immigrants, including poor Italians seeking a better

life outside Europe and an English minority who came to supply its commercial

and professional class, Argentina suffered serious economic decline in the

mid-twentieth century. Discontent brought to power a populist Peronist regime,

so called after Colonel Juan Peron, its leader. Peronist mismanagement provoked

a military coup in the 1970s. When the military junta itself became unpopular,

it decided to restore its fortunes by reviving the claim to the Falklands.

Recovering the Malvinas was a cause around which all Argentinians could unite.

Britain was long used to Argentina’s Falklands demands. It

did not take their revival in 1981–2 very seriously. Negotiations proceeded at

the United Nations in New York: they were not marked by urgency and the British

found the Argentinians in reasonable mood. Unknown to Britain, however, the

junta, led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, had already decided to mount an

invasion at latest by the October of 1982, when it was calculated that the only

Royal Naval ship on station, the ice patrol vessel Endurance, long scheduled

for retirement, would have been withdrawn. As late as March 1982, no military

preparations had been made and no diplomatic crisis appeared to impend. Then

what seems a chance factor altered the tempo. An Argentinian scrap reclamation

party arrived at Leith in South Georgia, the Falklands dependency, declaring it

was there to dismantle an old whaling station. The scrap men raised the

Argentinian flag but failed to seek permission for their work from the local

station of the British Antarctic Survey, the government authority. When

visited, they hauled down the flag but did not regularise their presence.

Constantino Davidoff, their leader, denied then and afterwards that he was

sponsored by the Argentinian navy but he is believed to have had a meeting with

naval officers before landing. Once he was ashore, the British Foreign Office

felt it had to act; the Ministry of Defence was more reluctant, since it

regarded operations 8,000 miles from home as beyond its capabilities. Under

Foreign Office pressure, a case was made to the Prime Minister, Mrs Margaret

Thatcher, who ordered Endurance, with a party of marines from Port Stanley, the

Falklands capital, to sail for South Georgia and to await orders.

The unexpected despatch of Endurance perturbed the junta. If

the scrap men were removed, Argentinian prestige would be damaged; but the

presence of Endurance challenged it to military action, which it did not plan

to take for several months. The Argentinians havered, first sending a naval

ship to take off most of the scrap men, then sending another with a party of

Argentinian marines to ‘protect’ those left. It was the turn of the British

government to dither. It sought guidance from its own and the American

intelligence services as to what Argentina intended. The signs were unclear.

Budgetary economies had run down the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) station

in Buenos Aires; what signal information could be supplied by Government

Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), by the American Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA) and by its sister signals organisation, the National Security Agency

(NSA), did not clarify the picture. The British agencies enjoyed a warm and

co-operative relationship with the American, based on much exchange of mutually

useful material; but the CIA depended on MI6 for human intelligence, while both

GCHQ and the NSA were confused by the volume of radio traffic suddenly

generated in the South Atlantic by Argentinian but also Chilean vessels; the

two navies were conducting a large-scale but routine exercise.

Britain fell into a week-long bout of indecision; it had

decided it could not tolerate any further Argentinian intervention in the

affairs of its South Atlantic dependencies; but it shrank from any overt

measure that would provoke Argentina to action. Eventually, the decision was

taken out of its hands. On 26 March, the junta, under pressure from street

demonstrations against its economic austerity programme, but even more fearful

of public reaction if it appeared to back down before British diplomatic

protest over the South Georgia affair, decided to advance the timetable for its

invasion of the Falklands and launch the operation at once.

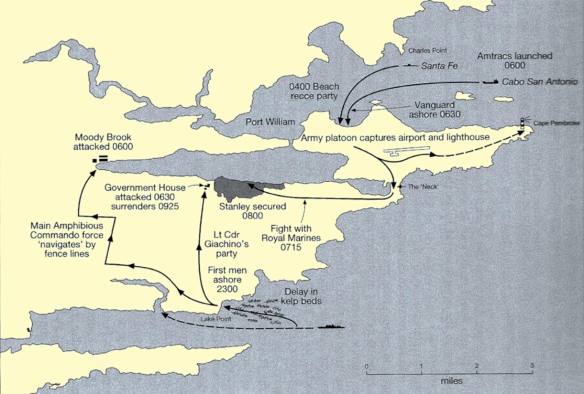

The Falklands were effectively undefended. Of their

population of 1,800, 120 of the men belonged to the Falklands Islands Defence

Force, but they were untrained and equipped only with small arms. An official

British military presence was provided by Naval Party 8901, a detachment of

forty Royal Marines; their number had recently been doubled by the arrival of

their reliefs. Apart from Endurance, currently in Antarctica, there were no

naval ships in the Southern Hemisphere. The Argentine armada, which began to

land at dawn on 2 April, could not therefore be repelled, though it was briefly

opposed. Naval Party 8901, depleted by the despatch of twelve men to reinforce

South Georgia, was ordered by the governor, Sir Rex Hunt, who had been warned

by London that an invasion force was at sea, to guard the airfield and the

harbour. When an advance party of 150 Argentinian commandos landed, they were

engaged and, in a firefight around Government House, two were killed. It was

clear to Sir Rex Hunt, however, that resistance was hopeless and, after two

hours, he ordered surrender. Soon afterwards the vanguard of 12,000 Argentinian

troops began to land, while the Argentinian air force took control of the

airfield.

The news caused an immediate and major political crisis in

London. The second of April was a Friday; an emergency session of parliament,

which never sits at the weekend, was called for the following day. The

consensus at Westminster was that, if the government could not demonstrate its

willingness and ability to confront the Argentinians, it would have to resign.

Fortunately for Mrs Thatcher, a woman of iron will but untried powers of

decision, she had already instituted precautionary measures. Alerted by the

enormous volume of radio traffic generated by Argentinian preparations, she had

ordered a submarine to sail for the South Atlantic on the previous Monday, 29

March. Much more important, indeed, as was to prove critically for the whole

Falklands saga, she had on Wednesday evening ordered that a naval and military

task force should be assembled to depart at once for the South Atlantic. Her

desire to recapture the Falklands was never in doubt; the impetus to the

decision was supplied by the arrival in her room in the House of Commons when

she was consulting her ministers of the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Henry

Leach, who gave it as his professional opinion that Britain had the power to

mount such an operation and that the navy could set out by the coming weekend.

He also assured the Prime Minister of victory. On return to his office he sent

a signal, ‘The task force is to be made ready and sailed.’

Its first elements departed on Monday 5 April, while its

military complement was hastily assembled in Britain to follow. Three

submarines, two nuclear-powered, one diesel, formed the spearhead; there were

to follow, over the course of the weeks to come, 2 aircraft carriers, embarking

20 Harrier aircraft and 23 helicopters, 23 destroyers and frigates, 2

amphibious ships, 6 landing ships, 75 transports, ranging in size from large

passenger liners to trawlers, and 21 tankers. The majority of the transports

and tankers were ‘taken up from trade’, chartered or requisitioned, that is,

from the merchant service.

The troops to be embarked would eventually comprise the

whole of 3 Commando Brigade (40, 42, and 45 Commando, Royal Marines, 29

Commando Regiment Royal Artillery and 59 Commando Squadron Royal Engineers),

attached to which were 2nd and 3rd Battalions The Parachute Regiment, two

troops of light armoured vehicles of the Blues and Royals, thirteen air defence

troops, the commando logistic regiment and the brigade’s helicopter squadron.

There was also a large complement of Special Forces, including three sections

of the Special Boat Squadron (SBS) and two squadrons of the Special Air Service

(SAS). To follow later was 5 Infantry Brigade (2nd Scots Guards, 1st Welsh

Guards and 1st/7th Gurkha Rifles) with some artillery and helicopters. The

Royal Air Force deployed elements of seventeen squadrons, flying fighters,

bombers, helicopters, reconnaissance aircraft and air refuelling tankers.

Refuelling, in the air and at sea, was an essential

requirement, for the task force was to operate without a land base nearer than

Ascension Island in the middle of the Atlantic. Until the airfield at Port

Stanley could be recaptured, air refuelling was less vital, for long flights

over the ocean could not be numerous. All fuel, and other supplies to the

warships, however, had to be transferred ship-to-ship while under way.

The assembly of the task force was a race against time, not

only because of the need to confront the Argentinians with an armed response as

rapidly as possible but also because of the season; the onset of the South

Atlantic winter at the end of June would bring sub-Arctic weather necessitating

withdrawal from the region. Everything, from completing dockyard maintenance to

supplying the soldiers with warm clothing, had to be done at the highest speed;

at the outset it seemed that many requirements could not be met.

It was not only the pace of material preparation that had to

be forced; so too did that of planning and intelligence gathering. The two were

intimately connected and interdependent. Britain had no base in the region and

no allies. Chile, long on bad terms with its Argentinian neighbour, was

disposed to be helpful but could not risk openly siding with Britain; most

other South American countries supported Argentina’s claim to the Falklands, if

only out of regional solidarity. How was the campaign to be fought? Clearly

there must be an amphibious landing but it would have to be launched from the

task force’s ships, not from land. That required the navy to close up to the

islands, at least while the troops got ashore, but also to remain nearby during

daylight so that the carrier aircraft could provide support. Worryingly the

islands, though 400 miles from the nearest stretch of Argentinian coast, were

just not far enough offshore to lie outside the range of the enemy’s land-based

aircraft. The troops, once landed, would be vulnerable to air attack. Far more

worryingly, the warships and transports would also be at risk, except when at

night they could stand off to the east into the broad expanse of the ocean.

How serious was the risk? That proved, both at the outset of

the campaign and during its development, an embarrassingly difficult question

to answer. No one in Britain really knew; no one, indeed, knew anything much

that was useful about Argentina’s armed forces. For reasons of economy, the

Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) had closed down all but one of its stations

in South America; that remaining was in Buenos Aires but its chief was too

overworked to collect anything but political intelligence. The service

attachés, navy, army and air, were supposed to report on their Argentinian

opposite numbers; but in recent years they were more often required to act as

salesmen for the British defence industries, so the excuse went afterwards; in

practice, attaché appointments were final postings at the end of a middling

officer’s career, a farewell present for an unexceptionable life. This was not

particular to Argentina but the general rule; only those officers posted to the

Soviet Union had the duty of acquiring intelligence and were fitted by ability

and training to do so.

Yet the collection of pertinent information in any

reasonably open society, which Argentina was, is not difficult and need not

conflict with diplomatic propriety. Readily available service magazines contain

valuable snippets of information which, if collated, quickly yield an order of

battle; so do local newspapers, from stories about local men in uniform and the

social affairs of locally stationed units. Service histories are also fruitful

sources; units tend to occupy the same barracks for decades. Armies, and

navies, are relatively unchanging organisations and, to anyone who takes the

trouble to form a picture of their organisation, rarely conceal secrets about

their location, strength or function requiring specialised intelligence

scrutiny to uncover.

The archives of the Defence Intelligence Service in London

ought, in short, to have contained copious and detailed reports on the

Argentinian navy, army and air force in April 1982. They did not. The cupboard

was almost bare. The officers of the task force have in consequence left a

record of a shaming and hurried search in public libraries for such standard

works as Jane’s Fighting Ships and the Institute for Strategic Studies’

Military Balance. Little was to be found. The Military Balance allots no more

than two or three pages to a country the size of Argentina; Jane’s Fighting

Ships is largely a photographic album. Moreover, as the most important of

Argentina’s warships, the carrier Veinticinco de Mayo, was the ex-British HMS

Venerable, venerable indeed since launched in 1943, and three of its largest

destroyers were British-built or designed, Jane’s could tell little the British

did not know already. The marines and soldiers scanning the Military Balance

must have been even more disheartened. It lists the barest information of

numbers of units and quantities of equipment and those in separate sections; no

picture of units’ capabilities is discernible, therefore, while units are not

named nor are their peacetime locations specified. That omission may have been

seriously misleading in the frenzied days of early April 1982. The Argentinian

army’s three best formations were the VI, VIII and XI Mountain Brigades (Peron,

incidentally, was a mountain infantry officer), which, by reason of their

training and familiarity with cold climate, seemed the obvious choice for

Falklands duty. Because of the junta’s fear that Chile might profit from their

commitment to the Falklands to strengthen its position in the disputed Cape

Horn region, however, it had left the mountain brigades in their peacetime

stations and decided to employ lower-grade formations drawn from the warm

borders of Uruguay. GCHQ is known to have been intercepting the mountain

brigades’ radio traffic, confirming that they were still located in the far

south even as the invasion fleet put to sea. The task force officers,

apparently dependent wholly on scantily published information about the

location and capability of their potential opponents, did not even know that.

The navy was quite as badly informed. Admiral Sandy

Woodward, commanding the warships and transports aboard the old carrier Hermes,

had a general picture of the risk he faced. It consisted of three elements:

attack by land-based Argentinian aircraft, some of which were equipped to launch

Exocet, the French-supplied sea-skimming missile (also aboard some of

Woodward’s ships), which was difficult to distract by electronic

counter-measure and deadly if it struck home; the Argentinian surface fleet,

known from radio intercepts to be at sea and organised in two groups formed

respectively around the Veinticinco de Mayo and the ex-American heavy cruiser

Belgrano, apparently deployed to mount a pincer movement; and Argentinian

submarines. The diesel-propelled submarines were known to be difficult to

detect but, it was believed, could be held at bay by the British nuclear

submarines in the area; the surface fleet had been warned not to enter an

‘exclusion zone’ proclaimed around the islands by Britain and would be attacked

if it did (it did not but was attacked anyhow, by HM Submarine Conqueror, and

Belgrano sunk); it was hoped to overcome the Exocet threat by positioning

destroyers and frigates as radar pickets between the islands and Argentina to

provide early warning and to distract any missiles that got through by firing

‘chaff’, which simulated a larger target than the threatened ship.

In practice the two Argentinian diesel submarines did not

manage to attack the task force; the surface fleet, partially incapacitated by

equipment failure aboard the Veinticinco de Mayo, turned back from the

exclusion zone and returned to port after the sinking of the Belgrano. The

Exocet aircraft, by contrast, inflicted heavy damage on the task force and,

with others delivering more conventional ordnance, came close to achieving a

naval victory that would have secured the Falklands and humiliated Britain for

decades to come.

The Argentinian air-launched Exocet, a modified version of

the maritime model, known as the AM-39, was mounted on a Super Etendard

aircraft, supplied by France, like the missile itself. The British believed

correctly that Argentina had only five AM-39s, but wrongly that it had only one

Super Etendard; the right number was five. As important as the aircraft–missile

combination was the maritime reconnaissance aircraft that alerted the Super

Etendards at their Rio Grande base to the presence of the task force within

attack range. An antiquated American aeroplane, the SP-2H Neptune, it possessed

the capability to linger beyond the horizon formed by the earth’s curvature but

to keep the British under radar surveillance by bobbing up over it at regular

intervals. The Super Etendards, when vectored towards the target, flew at sea

level, beneath British radar, until close enough for the Exocet to strike. The

pilots needed to gain altitude only once or twice, and then briefly, for their

own radars to acquire their targets and automatically programme the missiles to

depart in the correct direction. Once launched the Exocet maintained height

just above sea level by an on-board altimeter and finally homed on the target

ship down the beam of its own radar.

Admiral Woodward and his staff had been wrongly informed

that the Super Etendards’ range was only 425 miles, too short to reach the task

force east of the islands. In fact, by refuelling from one of Argentina’s two

KC-130 tankers, they could achieve launch positions. On 4 May, two days after

the sinking of the Belgrano, two Super Etendards, flying from Rio Grande,

approached the task force; their directing Neptune had been spotted by British

radar but was thought to be searching for Belgrano survivors. Glasgow and

Coventry, deployed as radar pickets west of the task force, caught echoes of

the attacking aircraft as they rose above the horizon to correct their final

approach paths. The British ships fired chaff and both Exocets, travelling only

six feet above the sea, were deflected by their own course-corrections.

Sheffield, twenty miles distant, was currently transmitting on its radio link

to satellite, which prevented its hearing the warnings transmitted by its

sister ships or operating its own radar. Its crew were therefore oblivious of

impending danger and neither fired chaff nor manoeuvred. She was hit in the

forward engine room by one of the Exocets which, though its warhead failed to

explode, started a fire that eventually forced her abandonment, after heavy

loss of life.

The manifestation of the Exocet threat was to exert a

decisive effect both on the management of the campaign and on the intelligence

effort that underlay it. Admiral Woodward at once withdrew the task force far

to the east of the islands, where it was to remain until the landings began on

21 May. At the same time the Northwood joint services headquarters, from which

Operation Corporate, as the campaign was code-named, was directed, began a

frenzied search for means to improve intelligence collection and to strike

directly at the Argentinian air menace. Of signal intelligence there was no

shortage; the Argentinian army, navy and air force generated a large volume of

traffic, which was intercepted not only by GCHQ, through its intercept station

at Two Boats on Ascension Island, ostensibly a branch of the Cable and Wireless

Company, but by the NSA, the American intelligence community having decided to

lend its British partners full support at this time of need, and by a New

Zealand intercept station at Waiouru. The United States was also generous with

satellite intelligence. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) had three

systems in operation that could together provide electronic and imaging data,

White Cloud, KH-8 and KH-11; it could also offer data from occasional

overflights by the SR-71 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft.

The limitation on the usefulness of overhead surveillance

was, first, its intermittence – White Cloud made only two passes a day – but,

second, that by the time it became available, the damage had been done.

Overhead surveillance could have warned of the Argentinian invasion fleet

setting sail, in time for the British government to have issued an ultimatum;

once the fleet had arrived, it could supply little further information that was

useful.

It was, among other factors, for that reason that the

Northwood headquarters decided, after the shock of the first Exocet attack, to

move from passive to active counter-intelligence methods. Since traditional

means of warning – including satellite intelligence – had failed to avert the

threat, the Ministry of Defence would be ordered to mount operations to

eliminate the risk at source. Britain’s special forces would be committed to

find and destroy the Exocet units in their home bases.

Read part II here: Intelligence Post WWII Part II