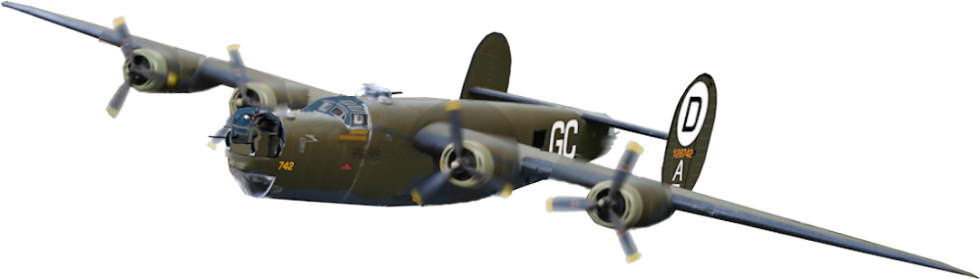

The routes flown on 14 January 1944 by the two sections of the 392nd BG.

British intelligence eventually identified four kinds of

Noball targets in France: heavy sites, ski sites, modified sites, and supply

and support facilities. It was the discovery of the nine large construction

sites in the Pas-de-Calais region and the Cotentin Peninsula near Cherbourg

that first captured the attention of British intelligence analysts. Throughout

1943 Organisation Todt’s building units, supported by thousands of slave workers

and conscripted civilian labor, began excavating and building what British

documents refer to as the “heavy” Crossbow sites. After the war, the Allies

discovered that the German air force had responsibility for four of these,

which were intended to store, assemble, and launch a large number of V-1 flying

bombs. Code-named “Wasserwerk,” or water works, by the Germans to hide their

purpose, these were primarily long tunnels with gaps in the ceiling to fire

rockets toward London. In the Cotentin, they built one in Tamerville, northeast

of Valognes, and the other at Couville, southwest of Cherbourg. The US Army’s

VII Corps overran both of these installations in late June 1944. The other two

were Lottinghen, east of Boulogne, and Siracourt, west of Arras in the

Pas-de-Calais. Siracourt was typical of these kinds of launching sites. The

dozen or so houses at the beginning of the war contained fewer than 140

citizens, mostly farmers and their families. The German army evacuated the

French civilians as Organisation Todt arrived in the spring of 1943. On a

little hill, just west of the village, contractors began construction in

September. This facility was to be the first of four to process, store, and

possibly fire the V-1. The main construction was 625 feet long and 132 feet

wide and oriented at a right angle to London. The 1,200 workers, primarily

Russians, Poles, Yugoslavs, and French forced labor, lived in a camp at

Croix-en-Ternois a little more than a mile away. Under the supervision of

Organisation Todt’s guard force (Schützkommando), the workers ultimately built

the structure and poured more than 50,000 cubic meters of concrete to make it

invulnerable to Allied bombers. Because of the bombing, however, it was

impossible to finish its construction. As a result, the Germans never fired a

flying bomb from it, and it fell to Canadian troops in September 1944.

The German army controlled the V-2 rockets, and it designed

large concrete installations, capable of launching seven to ten rockets per

day, with sophisticated storage and assembly capability. For example, the

launchers at Wizernes, next to Saint-Omer, lay beneath a massive concrete

cupola twenty feet thick and were capable of launching their rockets from two

platforms. Other sites at Watten (Éperlecques), near Calais, and Sottevast,

near Cherbourg, were just as massive and required millions of tons of concrete.

Forty-four miles north of Siracourt and eleven miles northwest of the Luftwaffe

airfields at Saint-Omer is the three-square-mile complex at Watten. On its

southwest corner, Organisation Todt built a massive structure that came to be

called the Blockhaus. It was an incredibly large structure that absorbed

thousands of tons of concrete and the forced labor of thousands of unfortunate

workers. Based on experience at the submarine pens along the coast, the German

engineers expected it to withstand the bombardment of whatever the enemy could

drop on top. The Allies never understood its exact purpose but knew they had to

destroy anything that was consuming so much German effort. It was the first

site detected by British reconnaissance. Duncan Sandys never believed it had an

offensive capability and, even after his visit in October, considered it to be

a plant for the production of hydrogen peroxide, which the Germans were using

as a fuel. Postwar records and analysis indicate, though, that it may have

served as a general storage, assembly, and launching facility in, according to

one researcher, “a bomb-proof environment.” Most experts believe it was capable

of launching rockets on its own.

Watten (Éperlecques)

Twelve miles south of the Blockhaus near Saint-Omer is the

village of Wizernes. In an old quarry, Organisation Todt constructed one of the

largest installations of the war, the V-2 launcher site known as La Coupole, or

the dome, for the most impressive aspect of the facility. Todt designed it to

assemble, fuel, and fire rockets from within the protected site. Upwards of

1,300 forced laborers worked on this project twenty-four hours a day. Like the

Blockhaus, it had two launcher ramps that could fire rockets simultaneously and

was probably the most sophisticated of the vengeance weapon launching sites. By

March 1944 British intelligence was convinced that it needed to be added to the

list of Noball targets. The most sinister of V-2 launcher sites was the silo

complex west of Cherbourg near La Hague. These, generally overlooked by Allied

intelligence, resemble the later American nuclear missile silos of the Cold

War. It never became operational, and the US VII Corps occupied this region in

July 1944. The problem for the Germans was that the construction crews could

not hide the extensive work sites from the hundreds of Allied reconnaissance

aircraft searching for signs of activity. The continuous bombing of the

extensive excavations in France meant the Germans could not complete the

launching facilities, which ended any possibility of the German air force using

them. Ultimately, the Germans would fire no V-2 rockets from fixed sites but

would employ mobile launchers that were essentially impossible for the Allies

to detect in advance.

Eleven miles from Cap Gris-Nez, across the channel from

Dover and ninety-five miles from the center of London, is a facility unique

among the heavy sites. The British knew the Nazis were developing a long-range

gun, but they did not know any details. The German army had done this before,

and Allied commanders had visions of a weapon similar to the artillery used to

bombard Paris in the previous conflict or the large guns deployed along the

French coast. Therefore, most analysts believed the construction at

Mimoyecques, France, was a variation on a V-2 launch site, since it bore no

resemblance to anything with which they were familiar. Also, since most of the

workers were German, few details emerged as to its actual intent. In reality,

the site housed something revolutionary, a large battery of long-range guns,

called Hochdruckpumpe (high-pressure pump) guns, later referred to by the

Allies as Vengeance Weapon-3. Each 330-foot smooth-bore gun was to be capable

of firing a six-foot-long dart about a hundred miles. Its range was the product

of added velocity created by solid rocket boosters arrayed along the edge of

the tube. Each projectile could carry about forty pounds of high explosives.

The plan was to construct banks of five guns each with the potential of firing

six hundred rounds per hour toward London. British intelligence knew little

about what was going on inside the facility. After the war, Duncan Sandys’

investigation of the large sites discovered the true nature of the threat they

had faced. Fortunately, Allied air attacks prevented Organisation Todt from

ever finishing its work and German gunners were never able to fire these

weapons.

The second kind of targets identified by Allied analysts

were the so-called ski sites, named from the configuration of several buildings

that looked like snow skis on their side. By late 1943 British intelligence

officers had identified between seventy and eighty of these, hidden in the

hundreds of wooden patches that dot the northwestern French countryside, with

their launchers pointed directly at their intended target. If left alone, each

one of these small installations could hurl fifteen FZG-76 flying bombs across

the channel each day. The cumulative effect of hundreds of these striking London

daily would not help civilian morale. They also posed a direct threat to the

harbors from which the Allies would launch and sustain the invasion. One of the

first sites identified by intelligence analysts was in the Bois Carré (Square

Woods) about three-quarters of a mile east of Yvrench and ten miles northeast

of Abbeville on the Somme. A French Resistance agent was able to infiltrate the

construction site in October 1943 and smuggle out some of earliest detailed

descriptions of a ski site layout. The long catapult, generally visible from

the sky and quickly identified by reconnaissance aircraft, became the signature

target indicator. As a result, even with extensive camouflage, they were

identified, targeted, and destroyed by Anglo-American aircraft. As a result,

none of these installations ever became operational.

Soon after the first air attacks, German leaders began

considering an alternative method of launching the V-1. Security and

concealment now became a priority, and these modified launcher sites were

better camouflaged and of simpler construction. These new launchers no longer

had many of the standard buildings, especially those that resembled skis, which

had contributed to their rapid discovery by intelligence specialists. With

minimal permanent construction, the only identifiable features were an easily

hidden concrete foundation for the launch ramp and a small building to set the

bomb’s compass. Other buildings were designed to blend into the environment or

to look like the local farmhouses. All this took less than a week to fabricate,

and forced labor no longer did the construction work, as German soldiers

prepared each site in secret. Supply crews delivered the flying bombs directly

to the launcher from a hidden location, assembled and ready to launch. All the

teams needed to do was set the compass and mount it on the catapult. Difficult

to locate from the air, these launchers would remain operational until overrun

by Allied ground troops in early September 1944. After that, the Germans

launched their V-1 rockets from sites in the Netherlands or from German bombers

specially configured to fire these weapons.

One week after the last V-1 flew from French soil, the V-2

rocket made its first appearance when it slammed into a French village

southeast of Paris, killing six civilians. The German army had abandoned any

hope of using large fixed sites for anything other than storage, and they now

organized the delivery of their rockets as mobile systems, structured around

less than a dozen vehicles and trailers. While the rocket was still hidden,

crews prepared it for launch, a process that took between four and six hours.

Within two hours of mission time, the firing unit deployed to a previously

surveyed site and erected the rocket on a mobile pad. As soon as it was on the

way, the soldiers disappeared into the woods, leaving little trace of the

launch. Unless an Allied fighter happened to catch the Germans during the short

preparation process, there was little the air forces could do to prevent

launches. The Germans fired none of the mobile V-2s from French soil, but fired

them instead from Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. While not part of the

discussion of bombing France, these rockets are an important reminder that the

Germans continued to use mobile sites until the end of the war.

The final kinds of Noball targets were the supply sites that

provided rockets for the individual firing units and the transportation network

that supported them. By February 1944 the Allies had determined that seven

facilities existed, one on the Cotentin Peninsula and the remainder arrayed

just east of the belt of launchers. These, however, were relatively difficult

to attack and were often located within underground bunkers or railroad

tunnels, under fortresses, or deep within thick woods. They also were often

protected by extensive anti-aircraft artillery. More vulnerable were the

various rail yards that served as offload and staging points for these systems.

Rail stations in Saint-Omer, Bethune, Lille, Lens, and Arras were the crucial

nodes in this network. Attacking these transportation nodes also supported the

goals of the Transportation Plan, the Allied attack of bridges along the Seine

and Loire, and Operation Fortitude, the effort to deceive the Germans as to the

actual location of the invasion.