An untested weapon often produces surprising results.

Sixteen-year old Ensign Mercutio Albert Palmer, having never dropped the

torpedo while underway and distracted to the edge of paralysis by shot whizzing

over and into his vessel, closed his eyes and misjudged the release. Rather

than striking Monitor at its waterline, as intended, the late release of the

torpedo caused it to strike the turret at the point where one of its Dahlgrens

exited the gunport. The resulting explosion funneled directly into the turret through

that gap, instantly killing every man inside with concussion as well as

igniting a powder charge being inserted into the cannon. Popping rivets

actually killed two men on Hart. Its way partially checked by the force of the

torpedo, Semmes’s ship still stuck Monitor hard enough to knock the Union

warship’s engine shaft out of alignment, though the vessel’s overhanging armor

prevented a rupture of its hull. Semmes, thrown from his feet by the collision,

ordered his engine put astern as flames poured from the shattered turret of the

now drifting Monitor. Within ten minutes, he had ascertained that four men had

been killed and two were missing (all from the bow of the ship), while six men

had suffered various injuries below deck. More importantly, his Hart’s heavily

reinforced bow had withstood the explosion and the ramming without major

damage. Ordering a replacement crew to ready a new spar torpedo, he steamed for

the Galena, now engaging the slower Alabama within range of the Rip Raps

battery. Closer to Fortress Monroe, Naugatuck’s iron hull was proving no match

for Virginia’s rifled cannon. With its single gun dismounted and the hull

shattered and leaking in several places, Naugatuck turned towards the open

waters of the Chesapeake at best speed.

Lieutenant Carter and the inexperienced crew of the

Confederate flagship were having a tough time of things. In a running battle

with the nimbler Galena, Carter had inadvertently allowed his vessel to close

with the heavy Union battery on the Rip Raps. At close range, the solid shot

could, if not penetrate, then severely buckle or loosen casemate armor. Worse,

such hits caused great splinters to fly from the oak backing of the plates,

killing or injuring a number of men in Alabama’s casemate. But disaster, when it

struck, came from a light pivot gun on Galena. Commodore Lynch had just ordered

Carter to close Virginia when a shell struck the observation slit in Alabama’s

pilothouse. Jagged metal splinters decapitated the Commodore, disemboweled the

helmsman, and ripped away Carter’s left arm. At full speed and rudder locked

amidships by the now unconscious hand of its captain, the flagship headed

directly into the Chesapeake—a beeline for the remainder of Goldsborough’s

squadron.

Galena turned to follow, but its first officer noticed Hart,

coming ahead at full steam. He ordered his guns turned on it a mere minute

before a parting shot from Alabama smashed into the quarterdeck, sending that

brave man to his eternal reward. Columns of water rose around Hart, a difficult

target due to its approaching aspect and its great speed. One round hit its

angled bow, and glanced away. Another whistled low over the deck before

penetrating the funnel. Then just as its spar torpedo dropped into contact low

on Galena’s stern quarter, a shot ripped completely through Hart’s unfinished

wheelhouse. Blasted by the force of the exploding torpedo, its wheel splintered

and its rudder swinging freely, Hart clipped the stern of the Union ironclad,

then began an uncontrolled, full speed turn back into the waters of Hampton

Roads. Galena, shipping water through its ruptured stern, quickly lost power

and grounded on a sandbar near the Rip Raps, out of the battle.

Though he had observed Semmes incapacitate Monitor, Jones

remained unaware of the tragedies playing out on Hart and Alabama, both of

which appeared to be moving under their own power and direction. His vessel had

suffered minimal damage thus far in the engagement, and since the commodore was

obviously taking his flagship directly for the remaining Union ships, how could

Jones not do likewise? Ordering full speed ahead, Jones was pleased to see that

both Virginia and Alabama would hit the Union line at about the same time.

Meanwhile, the wooden gunboats lagging behind the Confederate ironclads

increased their speed, except for Teaser, which slowed to pluck a battered

Ensign Palmer from the water, then closed to accept the surrender of the

smashed Monitor. The premier Union ironclad would eventually reach Gosport

under tow—a visible sign of Confederate naval might.

Goldsborough, having watched his strongest vessels shattered

by the Confederate ironclads, formed his 11 available ships into a line of

battle and waited for the oncoming enemy. Anchored by the 50-gun screw frigates

Minnesota and Roanoke, as well as the 44-gun sailing frigate St Lawrence (towed

by the steam tug Dragon), eight additional lightly armed screw and sidewheel

steamers prepared to greet the upstart Rebel navy with a storm of shot. As the

range closed, Virginia’s grizzled quartermaster whispered, “Looks like Hell’s a

comin’,” as the heavy Yankee ships disappeared behind a wall of flame-riven

smoke. A moment later, shot from the Union line rang like hail from the

casemate as it stripped away virtually every outside fitting and reduced

Virginia’s stack to an ill-drawing nub. Then thunder cracked as Confederate

gunners returned fire.

As Virginia approached the strong center of the Union line,

Alabama closed the more vulnerable side-wheelers forming its vanguard at the

oblique. Only as the flagship’s guns had fallen silent after engaging Galena

had executive officer Donald Clarence Collins, stationed on the gundeck,

discovered the carnage in the pilothouse. By the time the fallen men had been

carried below and control of the vessel regained, shot was again striking the

ironclad’s hull. Collins ordered fire returned, then a hard turn to port that

he hoped would bring the ungainly Alabama parallel to the Union line at close

range.

By the time Jones’s ship reached the enemy line, funnel

damage had reduced its best speed to less than four knots, allowing Roanoke to

dodge its dangerous ram with ease. Though three of Virginia’s guns were out of

action (one with its muzzle blown away, two more with shutters jammed closed),

those that remained raked Roanoke’s stern and Minnesota’s bow with devastating

accuracy. Two shot bounced the length of Roanoke’s gundeck, temporarily

disabling fully a third of its guns and puncturing its funnel between decks. As

thick black smoke filled the gundeck and poured from the vessel’s gunports,

panic seized some of the warship’s crew. They leaped into the chill waters of

the Chesapeake to escape a ship they thought aflame.

Though only one round stuck Minnesota, the gun captain

firing it had the presence of mind to load two bags of grape atop the solid

shot. The 1-inch balls scythed through the Union crews laboring at their heavy

bow chasers, and snapped lines and stays that whipped in their own dance of

death. The heavy shot smashed into the foremast of the steam-frigate. Its stays

cut away by grape, the mast toppled, crashing into Minnesota’s funnel as it

fell. Furled sails caught on the ragged edge of the stack, then ignited as

embers from the ship’s boilers spewed from below. Some guns fell silent as the

Union flagship’s captain ordered his men to deal with the more immediate danger

posed by fire and tangled wreckage. Those gunners remaining at their posts

redoubled their efforts as Virginia cleared the Union line and again crossed

their sights. To their amazement, the Confederate ironclad appeared to have

lost all headway, and was now drifting stern first less than 20 yards from the

Minnesota’s heavy artillery.

Alabama’s turn to port had placed it less than 50 yards from

the Union van, four wooden sidewheelers equipped with one or two medium caliber

guns each. To Lieutenant Collins, gazing from the battered vision slit of the

abattoir that was Alabama’s pilothouse, this seemed an unequal contest as his

heavier guns shattered the sidewheel of the leading vessel. A roar accompanied

the explosion of its boiler, taking the now sinking vessel out of the contest.

He changed his mind when the fourth ship in line turned towards his ironclad,

the reinforced ram at its bow looming larger by the second. With one of

Alabama’s bow pivot guns engaged to starboard and unaware of the menace fast

approaching, the other had time for only one round before the ram would

strike—and it missed. The bow-to-bow collision tossed the men of both ships

like rag dolls. Had the Yankee ram struck Alabama at a right angle, it may well

have penetrated its thinner hull armor. As it was, the Union steamer’s

reinforced bow glanced off the even heavier prow of the ironclad, then scraped

the length of its port side. The scraping did little damage to the ironwork of

Alabama, but the starboard paddlewheel of the Union steamer smashed itself

against the Confederate ship’s hardened bow. Then, pressed firmly against the

enemy hull by its rapidly spinning port paddlewheel, the steamer’s frail wooden

sides encountered the projecting eaves of Alabama’s casemate. The iron eaves

gouged several planks from the Union vessel’s side. Ten minutes later, the

damage so severe that its crew could not stem the inrushing sea, the plucky

steamer sank. By that time, the two remaining steamers had turned out of line,

hoping that rapid maneuver would serve where armor was lacking. Collins left

them for his wooden consorts now joining the battle, and shaped a course for a

cloud of smoke less than a half mile away. The stab of flames within it marked

the location of an uneven battle between Virginia and the remainder of the

Union fleet.

The Virginia drifted, boxed by the three Union frigates and

the four smaller vessels that had trailed them. In some sense a victim of its

own success, its single screw had fouled a length of hawser lost by Roanoke

early in the engagement. Over a dozen shells a minute, some fired ranges of

less than 30 yards, struck Virginia as it lay helpless. Even an ironclad had

its limits, and sheared bolts and oaken splinters screamed inside its hellishly

hot, smoke-filled casemate. One enemy shell exploded as it struck an aft

gunport, shutters already jammed open by an earlier blow. Upending a Brookes

Rifle and killing every man of its crew, the carnage from that single shot

added a little more depth to the inch of blood already seeking drainage from

the casemate’s deck.

Deafened by the cannonade, Jones felt rather than heard the

cessation of Union shot ringing on battered armor as he staggered from the

pilothouse across the shambles of his gundeck to check his remaining two guns.

Had the squadron finally arrived? He glanced through a shattered gunport in

time to see the reinforced bow of a Union gunboat block his view. Deaf or not,

he heard the crushing blow delivered to the mid-section of his command. Flung

to the deck, Jones’s world turned red as the blood of his dead filled his mouth

and eyes while pain coursed through his newly broken left arm. Consciousness

briefly fled, its restoration matched the return of a hail of enemy shot. Below

deck, his crew fought to staunch seams sprung by the enemy ram. Virginia’s

three inches of good Tredegar iron backed by 24 inches of solid oak had

held—barely. Wiping blood from his eyes, Jones looked again through the

shattered port. The Union gunboat, disabled by a fortunate shot from one of his

remaining guns, limped slowly away, but a brief rift in the smoke showed a

second ram, scarcely 300 yards distant, bearing down on the helpless Virginia.

The smoke dropped again, and Jones braced himself for the blow to come, and for

the death to follow. Finally the steamer, a vee of water streaming from its

bow, surged from the manmade mist—on a course that would miss Virginia

completely! Jones did not trust his eyes as a ragged fellow, blood dripping

from numerous wounds and one hand on the remaining spokes of a splintered

wheel, saluted his command. Thirty seconds later, Raphael Semmes slammed Hart

of the Confederacy into the side of Roanoke.

Of the five men crowded around Hart’s poorly shielded wheel

when Galena’s shot had struck home, only Semmes survived. Dazed and bleeding

from numerous lacerations (upon his eventual death at age 79, an autopsy would

recover seven metal splinters lodged in his body from this day’s action), it

had taken long minutes for his crew to extract him from the wreckage and to

regain control of their ship. Having broken immediate contact with the enemy,

Semmes paused to take stock of his vessel. Though the attack on Galena had

destroyed the spar torpedo fittings and wrecked the quarterdeck of his command,

neither speed nor maneuverability had been impaired. His guns had fired only

one or two rounds each so far (at high speed—Semmes’s preferred speed—fire was

inaccurate and water tended to enter through their gunports). Most importantly,

the ram-bow showed no sign of weakness or leakage.

Then Semmes ordered full steam for the distant cloud of

smoke surrounding the engagement between Goldsborough and the Confederate

squadron. Circling the rear of the Union line, Hart rammed a surprised gunboat,

shearing completely through its foredeck, then slowed to let his guns engage a

second steamer before aligning his warship on the center of the smoke covered

fracas. Gathering speed, he saluted Virginia (which from visible damage, he

expected to sink anytime), then rammed one of its three large tormentors.

Roanoke, already battered by shots from Virginia and now engaged on its

starboard side by Alabama, immediately began to sink. Locked into his prey by

the inrush of seawater, Semmes backed engines to no avail. The weight of the

sinking vessel pulled Hart’s bow so far down that the tips of its rapidly

spinning screw actually emerged from the sea. Then Hart popped free, though not

without cost as its abused engine coughed and died. Cursing, Semmes ordered his

guns to open fire on Minnesota and his engineers to get the engine working.

Caught in a crossfire between the remaining guns of the Confederate ironclads,

the bulk of his squadron sunk or dispersed beyond his control and his own ship

heavily damaged, Goldsborough ordered his flag hauled down. At 2.58 p.m. on

April 12, St Lawrence, unable to escape in the light onshore breezes, followed

suit. Only the tug Dragon and the damaged Naugatuck escaped the debacle to take

word of the defeat to Washington.

To Victory

Rumor spread, and with it panic: the strong Rebel squadron

was steaming up the Chesapeake; it would bombard Washington and bring Maryland

forcibly into the Confederacy; it had been sighted in Delaware Bay, heading for

the shipyards of Philadelphia or the teeming docks of New York. While governors

and mayors sent telegram after telegram to the White House begging for soldiers

and guns, Union Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, ordered ships scuttled to

block the Potomac, and Lincoln sent the few regiments that he could spare to

Baltimore, intent on holding Maryland in the Union. More than aware of the

vulnerable position of the slow-moving McClellan’s Army of the Potomac on the

James Peninsula, Lincoln ordered him to capture Richmond now or to begin

shifting his army back to northern Virginia. Convinced by Confederate deception

and the incompetence of his personal intelligence operatives that any advance

on Richmond would meet defeat at the hands of superior numbers, Little Mac called

for transports and hunkered in his entrenchments opposite Yorktown. The

besieger had become the besieged.

In truth, the victorious Confederate ironclads were in less

than pristine condition. Jones, his broken arm in a sling, took command of the

Alabama, and the heartbreakingly battered Virginia limped for Gosport with some

200 of the squadron’s wounded aboard. The severely handled prize Minnesota went

with it. Semmes, his engines repaired, reported to Jones that his vessel was

ready for combat, hiding the fact that long stints at the pumps were required

each hour to keep Hart afloat, and that, despite the efforts of his engineer,

Hart’s steam plant could offer only 12 knots at best. Anchoring the St

Lawrence, its cannon manned by gunners rapidly shipped from Gosport, to block

entry to the harbor at Fortress Monroe, Jones left two gunboats to support it

and steamed with the remainder of his squadron around the Peninsula and into

the York River. For four weeks, his squadron reinforced by a trickle of Confederate

gunboats converted from captured Union transports, Jones blockaded the James

Peninsula. Daily skirmishes with Union gunboats took a toll on both sides, but

few supplies arrived for the trapped Union army, and even fewer men were

successfully withdrawn from the peninsula. Virginia, its worst injuries barely

repaired and its guns replaced, rejoined the squadron in ten days. Jones

returned to its deck in time to face a Union fleet hastily recalled from a

planned invasion of New Orleans and intent on breaking the blockade and

extricating the hungry and demoralized Army of the Potomac. In exchange for his

right eye, lost to a cutlass when desperate Union sailors actually boarded

Virginia, Jones won the Second Battle of the Capes.

Meanwhile, in the fertile Shenandoah Valley of Virginia,

Confederate General Jackson smashed the Union forces arrayed against him once

Stanton shifted regiments and even brigades from that arena to defend

Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York from a feared invasion. Then

he entrained his battle-tested corps to support the Confederate siegelines at

Yorktown. The hurried recall of Union troops from the western fields of battle

to the east allowed Confederate forces to recover from the bloody struggle at

Shiloh Church in early April and regain Nashville. On April 30, Commodore

Buchanan led two new ironclads and a score of wooden warships down the

Mississippi from New Orleans and soundly defeated its Union blockaders. Wiring

Richmond that “The Father of Waters again runs unvexed to the sea,” he then

directed his vessels in a lightning campaign that saw all significant Union

naval presence driven from the Gulf of Mexico.

On May 15, President Abraham Lincoln slumped at his desk.

Two messages rested between his outstretched arms. One, a request from

McClellan to be allowed to surrender his starving army to the Confederacy,

noted that General Robert E. Lee (the replacement for General Joseph E.

Johnston, wounded by a Union sharpshooter in front of the Yorktown lines)

offered most generous terms. The other, delivered that morning by the

ambassador from Great Britain, declared that Britain would soon move to

recognize the Confederate States of America formally as a sovereign nation with

all the rights thereof. Her majesty’s ambassador had advised the president that

where Britain led, the remainder of Europe would soon follow. Further, Union

interference with British trade into ports where, obviously, a blockade no

longer existed, would be met with far more than words. Three days later,

McClellan surrendered his army to General Lee and Fortress Monroe to Captain

Catesby ap R. Jones of the ironclad Virginia.

Aftermath

On June 30, 1862, representatives signed the treaty that

officially ended the brief Civil War and recognized the Confederate States of

America as a sovereign nation in its own right. Ten years later, June 30 would

become an official holiday in the Confederacy: Navy Day, in honor of the

service that had contributed so much to establish the new nation. That

particular day would never be celebrated in the old Union, where flags still

fly at half-mast and 26 forever empty seats in the senate chambers are draped

in black each June 30—a silent protest at what Mallory and his navy once

accomplished.

The Reality

Stephen Mallory, though he did much in creating a navy for

the Confederacy, did not perform the miracles needed to win independence for

his homeland. Be thankful for that. Victory would have meant the continuation

of the institution of slavery, an institution that the South would not have

willingly abandoned for generations (if at all). Even now, the lingering

remnants of the mentality created by that old evil erodes much slower than one

could wish.

Sherman, in his letter to David Boyd, had the right of it.

The greater resources and mechanical might of the North created a basis for

victory almost impossible for the weaker Confederacy to overcome, while the blockade

discouraged the importation of war materials desperately needed in the South.

Add to that the disorganized and sometimes almost inexplicable actions of the

Confederate state and national governments, and the miracle is that the

rebellion continued into 1865. Nowhere was the disorganization of the

Confederacy more apparent than in its attempts to construct a navy.

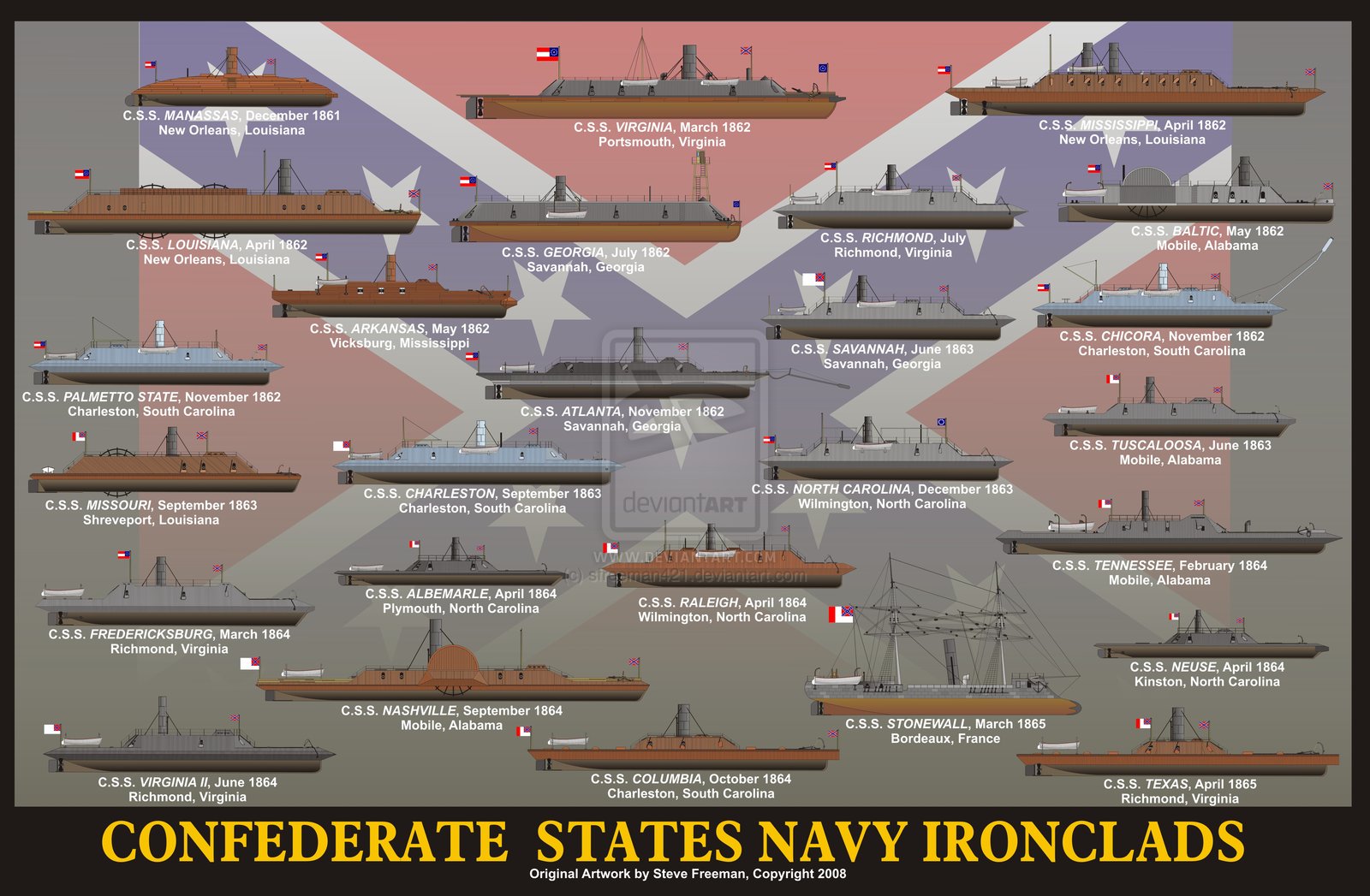

The Confederacy laid the keels for over 20 ironclads (in

almost as many locations as there were warships built). Often constructed in

cornfields instead of proper yards, this haphazard collection of vessels was

meant to challenge the offensive might of the ever-strengthening Union Navy.

Unsurprisingly, the challenge failed. Built of often sub-standard materials by

unskilled labor, the ironclads were invariably underpowered. Strive as bravely

as they might, the inexperienced crews of Confederate ironclads were unable to

resist Northern incursions, especially those supported by concentrations of

Union ironclads, much less break the blockade of Confederate ports.

Yet control of the sea offered the best chance for the South

to win the Civil War. Its ports kept open for European imports and a denial of

Union amphibious capability would have concentrated more resources in Southern

armies. Perhaps with more resources, the talented commanders of Confederate

armies could have won the key struggles ashore. Or, perhaps, had Mallory been a

true Southern Themistocles, the Confederate States Navy could have won the war

for them.

Bibliography

Denny, Robert E., The Civil War Years: A Day-by-Day

Chronicle of the Life of a Nation (Sterling Publishing, New York, 1992).

Foote, Shelby, The Civil War: A Narrative, Fort Sumter to

Perryville (Random House, New York, 1986).

Miller, Nathan, The U.S. Navy: A History, 3d ed. (Naval

Institute Press, Annapolis, 1997).

Morrill, Dan, The Civil War in the Carolinas (Nautical &

Aviation Publishing Company of America, Charleston, 2002).

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the

War of Rebellion, (Government Printing Office, Washington, 1894–1927).

Still, William N., Jr., Iron Afloat: The Story of the

Confederate Armorclads (University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 1985).

Symonds, Craig L., The Naval Institute Historical Atlas of

the U.S. Navy (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1995).

By Wade G. Dudley