The defence of the Indian Ocean became an increasingly

important factor in British strategic calculations during the first half of

1941. They also showed how American determination to prioritise the Atlantic

over the Pacific obliged the Royal Navy to resurrect the concept of an eastern

fleet to ensure adequate security against Japanese intervention in the war. For

a number of reasons, the mid-point of the year marked a watershed for both

Britain and the United States in their perception of the risk from Japan, and

the start of a series of moves on both sides that led inexorably to

confrontation at the end of the year. The Royal Navy’s intelligence picture of

the naval risk posed by Japan in mid-1941, as the prospects of her intervention

increased, and as it became both possible and necessary to contemplate

deploying significant naval reinforcements to the East. It also looks at the

overall resources and capabilities available to the Royal Navy at this time to

secure Britain’s vital interests across the wider eastern empire and to provide

any necessary reinforcements.

The Royal Navy picture of the IJN in 1941

For most of the interwar period, the Royal Navy viewed the

IJN as both its most likely opponent in a future war, and the only naval power

that posed a significant threat. In terms of size, the IJN ranked third after

the Royal Navy and US Navy, its fleet spanned the full range of naval

capability, it had established a fine tradition, and was recognised as an

innovator. It was by any measure a powerful force, and therefore a key standard

against which the Royal Navy judged its strength and capability. The strength

of the IJN, current and projected, was not only a key determinant of the Royal

Navy rearmament programme from 1935 onward, but had also shaped Royal Navy

programmes in the 1920s and early 1930s, especially for cruisers and

submarines. The specifications of the County-class cruisers laid down from 1924

were largely dictated by IJN cruiser plans following the 1922 Washington Naval

Treaty. The Southampton class laid down from 1934 were strongly influenced by

the Mogami class. The ‘O’-, ‘P’- and ‘R’-class submarines, laid down between

1924–29, were specifically designed to hold off an IJN fleet in the South China

Sea, pending the arrival of the main Royal Navy fleet. Until 1940, defence of

the Far East was seen as pre-eminently a naval problem, and the Admiralty

dominated Far East defence policy and planning. Before 1937, this policy and

planning had a theoretical quality, but Japan’s invasion of China increased the

risk of confrontation, and the prospect of an attack on British possessions.

The 1937 imperial review and Far East appreciation represented a watershed in

judging those risks. For all these reasons, the Royal Navy studied the IJN

closely, drawing on both overt and secret intelligence sources.

The Royal Navy’s intelligence picture of the IJN has

received contrasting reviews. One influential interpretation is that poor

intelligence and wishful thinking allowed the Royal Navy to create an image of

the IJN that made it less threatening, and hence easier to manage. As the Royal

Navy increasingly struggled in the late 1930s to provide a fleet to match the IJN,

so it sought convenient evidence that Japan could neither sustain nor make

effective use of a superior fleet. This led it to set IJN efficiency at 80 per

cent of the Royal Navy, to underrate Japanese technical and industrial capacity

and to believe that the IJN would be a cautious opponent. These factors

encouraged a disastrous reliance on inadequate forces, culminating in the Force

Z deployment at the outset of war. This interpretation focuses too much on what

was not known, rather than emphasising what was known and then concentrating on

key gaps. It also fails adequately to distinguish between what was knowable and

what was not knowable. It was not possible to predict the timing of a Japanese

attack on Malaya with any certainty before autumn 1941, because no firm plan

existed before then. Nor could the Royal Navy have predicted prior to 1941 that

the IJN would group all its fleet carriers in a single task force to deliver

strategic effect, because the IJN did not adopt this concept until early that

year. Finally, it does not place intelligence within the wider context of

political and military risk management. Perceived intelligence weakness must be

weighed against the fact that British assessments of the forces the Japanese

would deploy against Malaya were consistently good.

An alternative view of British intelligence performance in

the run-up to war concedes that the Royal Navy’s assessment of the IJN was

mediocre, but argues the failings were compensated by system and circumstances.

Royal Navy strategy, based on ‘bean-counting’ of warships and a rejection of

best-case planning, was not distorted by any underestimation of Japanese

quality, nor was the latter responsible for the loss of Force Z. The Royal Navy

may have failed sufficiently to recognise IJN technical achievements and

innovation in tactical thought, especially in the use of naval air power,

through the late 1930s. However, this was not in itself responsible for

Britain’s inadequate dispositions in the Far East in December 1941, which were

more the result of circumstances and the demands of grand strategy. Royal Navy

intelligence failings would not, therefore, have been significant, had Britain

been able to despatch sufficient naval and air forces to the East to implement

a defensive strategy. Proponents of this view have also, rightly, stressed that

in planning for war with Japan, the Admiralty always wanted its naval forces to

be larger than they were, always preferred numerical superiority over the IJN,

and calculated the balance of forces on the basis that one Japanese warship

equalled one British warship of equivalent size.

In terms of unit numbers of IJN warships, Royal Navy

‘bean-counting’, or basic assessment of IJN order of battle, in mid-1941 was

fairly accurate, though not perfect. An assessment prepared by the Naval

Intelligence Division (NID) section responsible for Japan, NID 4, for the prime

minister in late August 1941 gave an authoritative statement of overall IJN

strength. This got most numbers correct. It overstated the number of

operational destroyers (126 compared with an actual strength of 112) and

submarines (eighty compared to sixty-five), but these errors were not

significant and may be explained by the inclusion of units in reserve. However,

the assessment also contained important mistakes in displacement and armament,

which represented a more serious underestimate of actual IJN fighting

capability, especially air power. It correctly identified eight aircraft

carriers, but underestimated the displacement of the fleet carriers Hiryu and

Soryu and the light carrier Ryujo by about 40 per cent. Overall aircraft

capacity of the eight carriers was put at 362 aircraft, compared with an

official IJN figure for embarked strength at this time of 473, an underestimate

of about a quarter. Six cruisers, the four Mogami class and two Tone class,

were mistakenly listed with 6in guns, whereas in reality they were all by this

time armed with 8in. (The four Mogami class were initially fitted with fifteen

6in guns, since Japan had reached its London Naval Treaty limit on 8in

cruisers, but they were designed to be upgraded, and this was done secretly in

the late 1930s. Both the Royal Navy and US Navy missed this. The Tone class

were built as 8in cruisers from the start, but NID 4 assumed they would repeat

the 6in pattern of the Mogamis. NID 4 did not correct this error, shared by the

Americans, until after the Battle of Midway when photographs of Mikuma and

Mogami showed their main armament was ten 8in guns. NID 4 then concluded,

rightly, that they had always been designed for upgrading to 8in, and assumed

the two Tones would now be similarly armed. Finally, the assessment included a

‘heavy armoured cruiser’ of 14,000 tons, armed with six 12in guns, on trials

which did not exist.

Estimates for the overall strength of the IJNAF produced

during 1941 were also broadly accurate. In May that year the Joint Intelligence

Committee assessed first-line IJNAF strength at 1496 aircraft, including 330

ship-borne. The figure for ship-borne air strength of 330 aligned closely with

the subsequent NID 4 estimate for the prime minister in August. Given that the

total included seaplanes and catapult reconnaissance aircraft, it

underestimated carrier-borne strength, even allowing for the fact that there

were only six carriers in commission at this time. (The large fleet carriers,

Shokaku and Zuikaku, were still in build.) Meanwhile, the Joint Intelligence

Committee assessed Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) strength at 886,

giving a total Japanese frontline strength of 2384. NID subsequently circulated

a figure of 1600 for IJNAF first-line strength in August and a later Air

Ministry Weekly Intelligence Survey in December 1941 quoted a total IJNAF

strength of 1561 with 547 ship-borne. The latter report set IJAAF strength at

1108, giving an overall Japanese frontline in December of 2669. By then there

were ten IJN carriers in commission, so deployed carrier air strength had grown

accordingly from the May estimates.

These estimates during 1941 compare with an official

Japanese figure for frontline IJNAF strength on the outbreak of war of 831

shore-based and 646 ship-borne aircraft, a total of 1477. British estimates for

ship-borne aircraft were fairly accurate for seaplanes and floatplanes, but

underestimated the carrier total by about 25 per cent (338 in December, as

opposed to a real total of 473). The estimates for IJNAF land-based bomber

strength were also in the right order, but there was otherwise no detailed

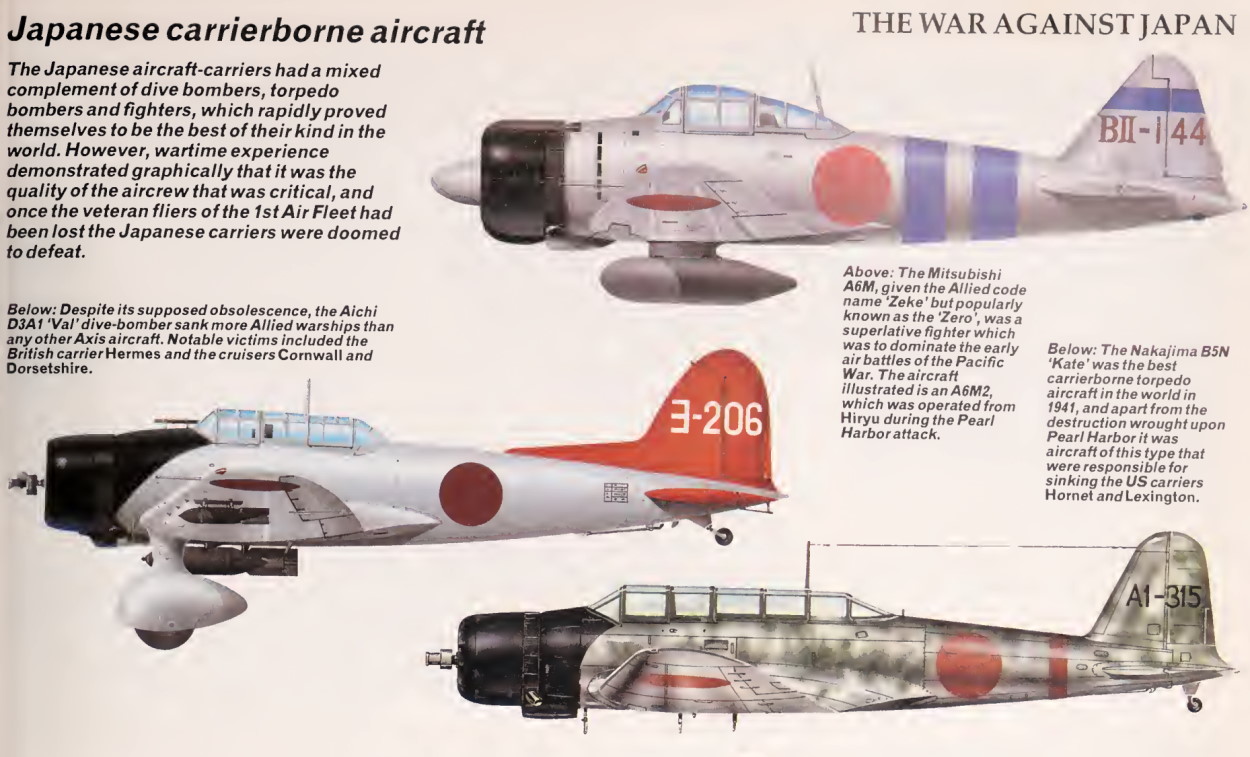

breakdown of either land-based or ship-borne strength into either category, ie

fighters, torpedo bombers, heavy bombers, etc, or specific aircraft type such

as A6M Zero, B5N2 torpedo bomber, or Type 1 bomber, etc. Alongside the above

estimates of frontline strength, evidence from early 1942 suggests that British

intelligence departments had a surprisingly accurate view on the size of the

aircraft reserve held by the Japanese at the start of the war. Drawing on Joint

Intelligence Committee advice, Ismay informed the prime minister in early March

that the immediate reserve at the start of hostilities for the two Japanese air

forces was 650 aircraft. Japanese figures show that the actual total for the

IJNAF operational reserve was 309.20 It is unlikely the IJAAF reserve was

larger, so a combined estimate of 650 was about right.

The Joint Intelligence Committee report of May 1941 did not

expect Japanese air strength to grow significantly over the next two years,

judging that production only balanced wastage and re-equipment. Wastage

calculations here, of course, took account of ongoing operational losses in

China. For the IJNAF, at least to end March 1942, this assessment was

essentially correct. In the summer of 1941, production of naval aircraft of all

types was only 162 aircraft per month and was only 179 per month over the first

four months of war. Production was especially slow for the more modern combat

aircraft, and this was compounded by the paucity of reserves noted above, which

represented barely 25 per cent or less of frontline strength. There were only

415 Zero fighters available to the frontline at the outbreak of war and, as

will be demonstrated later, carrier attack aircraft availability was depleting

fast well before the Battle of Midway in June 1942. Overall, these estimates

for immediate pre-war Japanese air strength, frontline, reserves and production

capacity were significantly better than the comparable estimates for pre-war

German air strength, and far superior to the estimates of German air strength

and production during 1940 and the first half of 1941. In 1939 German air force

frontline strength was overestimated by 18.5 per cent, while 1940 German

aircraft production was overestimated by a minimum of 23 per cent, and at one

point by about 75 per cent.

British military leaders have attracted harsh criticism for

their lack of knowledge of Japanese aircraft performance. Although surviving

records here are patchy, accurate performance tables for all Japanese aircraft

in use at the outbreak of war had been circulated across the British

intelligence community by mid-1941. The exceptional range of many Japanese

naval aircraft, including the new Zero fighter, was identified in these tables.

British intelligence also had a reasonably accurate picture of IJNAF aircraft

armament. The main types of bomb carried were known, as were details of the

Type 91 aerial torpedo. The capability of the Type 91 has often been

exaggerated, compared to the standard Royal Navy 18in Mark XII and XIV Fleet

Air Arm torpedoes. In fact, specifications, performance and reliability were

close. The Type 91 could, in theory, be dropped from up to 500m (1640ft)

altitude, but authoritative Japanese sources state that despite the optimistic

claims of the ordnance department, only 10 per cent would function correctly at

200m (660ft) and 50 per cent at 100m. In an operational context, the preferred

standard drop was from a range of 400–600m (1300–2000ft) at 160–170 knots at a

height of 30–50m (100–164ft). This was little different from the operational

performance envelope of the Fleet Air Arm Albacore, although the latter was

somewhat slower. This intelligence on aircraft and armament had been absorbed

within Far East air headquarters by early autumn 1941 at the latest.

As regards Japanese air deployment, an August NID report

identified eight Japanese airfields in Indochina, along with details of the

upgrades underway at Saigon and Bien Hoa, which would both be used by IJNAAF

aircraft that December. Significantly, this report also included a chart

showing the operational radius for heavy bombers deploying from Saigon and

Soctrang, demonstrating that Singapore and the Malacca Strait would be in range

of aircraft with a normal bomb load. A subsequent report provided details of

the Type 96 IJNAF heavy bomber, correctly estimating it could carry 2200lbs

(1000kg) to 950 miles. This report admittedly doubted Japan could afford to

deploy more than 150 land-based aircraft for potential operations against

Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies at this time, but this figure would be

revised sharply upwards over the next three months. In judging operational

effectiveness, Far East air headquarters drew a distinction between the IJNAF,

whose quality was rated high, and the IJAAF, who were rated mediocre. This

assessment would have been shared with the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB),

whose role is described shortly, and the China Fleet.

The Royal Navy’s primary measure of its strength against the

IJN was the number and quality of capital ships. Here it was certainly not

complacent. In March 1940 Churchill, then First Lord, sent a paper comparing

Royal Navy and IJN capital ships to the War Cabinet. It pressed the case to

resume building capital ships, suspended at the start of the war, in order to

ensure adequate capability against Japan from 1942 onward. However, the paper

is important for what it says about the existing balance. It stated that the

IJN battle-fleet, which had been completely modernised, had a speed at least

equivalent to the Queen Elizabeth class and considerably greater than the ‘R’

class. Japanese battleships also outranged the unmodernised Royal Navy ships.

The paper stated correctly that all ten IJN capital ships had received modern,

more efficient boilers and engines, new main armament guns of increased

elevation, probably to 40 degrees, additional armour, including horizontal

protection, and new anti-aircraft armament. It would be unsatisfactory to send

any Royal Navy ships to the East unless they matched IJN ships for both speed

and range. Only seven of the existing fleet did so. These seven comprised the

four Royal Navy reconstructions undertaken between 1934 and 1940, namely the

three battleships, Warspite, Valiant and Queen Elizabeth, and the battlecruiser

Renown, along with the two Nelsons and Hood. The four modernisations took

broadly the same form as the IJN applied to all ten ships, although there were

also two partial modernisations. The paper noted that although the new King

George V class would broadly match anticipated new IJN ships in numbers, they

would be out-gunned. In addition, Japan was believed to have four 12in gunned

battlecruisers in build.

The September 1940 Future Strategy paper confirmed this

assessment. It stated that Japan’s modernised ships were ‘superior to our own’,

and that the new battlecruisers could only be countered by a King George V or

Hood or Renown. NID 4 reminded Churchill of the IJN capital ship modernisation

programme in August 1941, as he was beginning the debate with Pound over Far

East naval reinforcement. In March 1942 the naval staff stated that there was

no recent information on IJN gunnery and RDF (radar), but there was no reason

why the IJN should not be ‘considerably superior in Long Range Direct Fire and

Medium Range Blind Fire’. The IJN had, in fact, put much effort into long-range

gunnery with significant results in trials, but this was based on traditional

techniques of visual ranging. They never produced effective firecontrol radar,

which the Royal Navy had in most capital ships by this time. Royal Navy anxiety

over IJN capital ship superiority persisted through most of the war. As late as

1944, a paper by the Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI) stated that the four

older IJN battleships of the Fuso and Ise classes were superior to the

modernised Queen Elizabeths while the Kongo-class battlecruisers were superior

to the modernised Renown, although it recognised Royal Navy radar could, in

practice, make a decisive difference. This assessment was undoubtedly unfair to

both the modernised Queen Elizabeths and Renown, but it reflected an enduring Admiralty

view. As regards gunnery performance, it is unlikely there was much difference

between the two navies in long-range fire under good daytime conditions, but

radar gave the Royal Navy a major advantage at night, or in bad weather.

An effective assessment of the Japanese naval risk to

British interests could not rest solely on bean-counting. It required knowledge

of IJN organisation, the location and movements of its key forces, their

fighting effectiveness and, above all, timely warning of hostile intent. Here,

despite limited resources, the intelligence capability available to NID by

mid-1941 was good enough to enable the Admiralty and local Royal Navy

commanders to reach reasonable conclusions on the scale, quality and timing of

an attack. To provide the Far East intelligence picture, NID relied primarily

on the Far East Combined Bureau, a joint intelligence organisation set up in

1936, combining personnel from all three services to support Far East

commanders. The FECB was a visionary concept for its day, and represented what

in modern parlance would be described as an all-source ‘fusion centre’. Its

primary roles were to give early warning of Japanese attack, build an accurate

Japanese order of battle, naval, land and air, and provide operational intelligence

once war had broken out. It also provided some set-piece assessments of

Japanese capability, and occasional strategic overviews. Although the FECB was

a tri-service organisation, because of the Royal Navy’s traditional

pre-eminence in Far East intelligence, it was accountable to and administered

by Commander-in-Chief China, not Commander-in-Chief Far East, and commanded by

a Royal Navy captain. In the second half of 1941 this was Captain Kenneth

Harkness. He was a gunnery officer, not an intelligence specialist, but

capable, with a strong operational record and a good administrator. FECB,

therefore, had a distinct naval bias. It devoted more effort to naval

requirements and was more effective here than it was for the other two

services.