Darius son of Hystaspes was not a man to be trifled with.

The Athenians had given earth and water. They had become his bandaka. Then they

had broken their bond. They had not only refused to take direction from his

satrap. They had supported the rebellion of the Ionians; and, with the

Eretrians, they had also participated in an attack on the capital of one of his

satrapies. They had ostentatiously embraced Drauga—“the Lie.” If Darius was

“the man in all the earth” and “King in all the earth,” as he claimed to be, he

could hardly let their insolence pass unpunished.

Darius prided himself on being “a friend to the right” and

“no friend of the man who follows the Lie,” and he knew how to be a friend to

his friend and an enemy to his enemy: “The man who cooperates—him do I reward

in proportion to his cooperation. He who does harm I punish according to the

damage done. . . . What a man does or performs according to his abilities

satisfies me . . . ; it gives me great pleasure and I give much to faithful

men.” Darius professed also to be steadfast in “intelligence” and “superior to

panic,” whether in the presence of “a rebel or not,” and he claimed to be

a good fighter of battles . . . furious in the strength

of my revenge with my two hands and my two feet. As a horseman I am a good

horseman. As a bowman I am a good bowman, both on foot and on the back of a

horse. As a spearman I am a good spearman, both on foot and on the back of a

horse. These are the skills which the Wise Lord Ahura Mazda has bestowed on me

and I have the capacity for their use.

There is no reason to dismiss these bold assertions as mere

propaganda. As King of Kings, Darius had nearly always been as good as his

word.

As one would then expect, in 491—after Mardonius had

consolidated Persia’s hold on Thrace and Macedon, and probably quite early in that

year—Darius took the next logical step. According to Herodotus, he sent out

heralds to the free cities throughout Hellas, “ordering that they request earth

and water for the King,” and at the same time he sent out another set of

heralds “to his tribute-paying cities along the coast, ordering that they

produce not only long ships but horse transports,” the first such of which we

have any report. His aim, we are told, was to discover “whether the Greeks had

it in mind to go to war with him or to hand themselves over.” The handwriting

was now on the wall.

In truth, it had been there for some time, and the Greeks

within the ruling order in each of the various cities had frequently given it

thought. In 494, the crucial year in which the battle of Lade took place, when

Cleomenes led the Spartan army against the Argives, it was surely not Argos

that he chiefly had in mind. Nearly two generations had passed since the Battle

of the Champions in the mid-540s. If Argos’ defeat on that occasion had been

followed by a peace of specified duration—thirty or fifty years, as seems to

have been the norm—it was no longer in effect. Moreover, whatever casualties

the Argives had sustained at that time had long since been recouped. Another

showdown over Thyrea was in the cards, and Cleomenes, who was no less vigorous

than he had been a quarter of a century before, was intent on crushing the

Argives well before the Persians could come.

We do not know how the trouble began. Cynouria, the

long-disputed district wherein the fertile Thyreatis plain lay, was easier to

get to from Argos than from Sparta. It is conceivable that there was a peace of

fifty years’ duration, that it ended in 496 or 495, and that the Argives then

seized the territory. It is also possible that, in this regard, they issued a

challenge, as appears to have happened fifty years before. What we are told is

that Delphi supplied an oracle to Cleomenes, predicting that he would take

Argos. It is a reasonable presumption that, in this exchange, Cleomenes took

the initiative—that, in accord with ordinary protocol, he sent one or more of

the four Púthιoι to Delphi to pose the question. Given what is known regarding

the Agiad king’s proclivities for the use of religion as an instrument of

political manipulation, it would not be surprising if he had made arrangements

in advance to secure the answer he had in mind. He is known to have done just

that on at least one other occasion. Cleomenes was not apt to be passive.

Nearly always, he was a man with a plan.

On this occasion, Cleomenes led his army to the Erasinos

River on the border of the Argolid. There, Herodotus reports, the omens were

not favorable —which may be an indication that it had come to the attention of

the Agiad king that the Argives had occupied the high ground on the other side

of the stream, or it may simply indicate that this maneuver was a feint. In any

case, undeterred, Cleomenes then retreated to the south and marched his army

east to the plain of Thyrea, where he sacrificed a bull to the sea and made

arrangements for the Aeginetans and Sicyonians to convey his army to the

district of Tiryns and Nauplia on the coast of the Argolid. If maritime

transport was not, in fact, prearranged, as I suspect it was, this must have

taken some time. Aegina was situated in the Saronic Gulf not far from Cynouria

and the Argolid, but Sicyon was located on the Corinthian Gulf. To get from

there to Thyrea on the Argolic Gulf, a ship must either circumnavigate the

Peloponnesus or be conveyed across the díolkos at Corinth.

The Argives appear to have been caught off guard by Cleomenes’

second approach. Herodotus tells us that they rushed to the coast and deployed

their troops near Tiryns at a place called Sepeia, leaving very little space

between themselves and the Lacedaemonians. They were nervous, we are told,

because, in an oracle issued to the Argives, doom had been predicted both for

the Milesians and for them. When Cleomenes learned that the Argives were paying

close attention to the orders issued by the Spartan herald and acting

accordingly, he instructed his men to ignore the herald’s announcement of the

mid-day meal and strike when, upon hearing this order, the Argives dispersed to

take their own meal. The stratagem worked. When the herald made his

announcement, the Lacedaemonians paused briefly, then attacked and routed the

Argives—who, in desperation, sought refuge and sanctuary in a nearby grove,

sacred to Apollo.

Cleomenes was nothing if not ruthless, and he was not put

off by the thought of committing a sacrilege. By one means or another, the

Spartans were able to secure the names of some of the survivors. On the Agiad

king’s order, they sent a herald to call these out from the grove one by one at

intervals by name, announcing that they had been ransomed for the standard fee.

When each of these came out, however, he was led away and executed. Some fifty

lost their lives in this fashion. Eventually, however, one of those trapped

inside the grove climbed a tree and discovered what was happening, and the

Argives stopped responding—at which point, Cleomenes ordered the helots with

his army to pile up brushwood around the grove and set it alight in order to

roust or roast the rest. All in all, we are told, the Argives lost something

like six thousand men in this encounter. This was the greatest loss of life

known to have been suffered in a single battle by a Greek city in the entire

classical period.

This catastrophe appears to have had profound political

consequences. Herodotus reports that, before heading home, Cleomenes visited

the sanctuary of Hera near Mycenae, north of the city of Argos, where he

insisted on conducting a sacrifice and had an attendant whipped who told him

that for an outsider to do so was a sacrilege. He does not mention any attack

on the city itself, and he implies that none took place. In other sources,

thought to be derivative from local histories, however, there are reports

suggesting that Cleomenes or a contingent from his army may at some stage, at

least, have approached the walls; and, tellingly, Plutarch mentions the name of

the Eurypontid king Demaratus son of Ariston in this connection. We are told,

moreover, that, in the absence of the city’s men, a woman named Telesilla

organized the defense of the city’s walls, rallying the old men, the young, her

fellow women, and the underlings attached to their households [oιkétaι] to

wield whatever weapons they could find and fend off an assault; and Herodotus

appears to be aware of this tradition, for the oracle he cites associates

Argos’ defeat with a victory and achievement of glory on the part of that

city’s women.

It is a reasonable guess that the oιkétaι mentioned by

Plutarch were drawn from the city’s substantial and downtrodden pre-Dorian

population. In the aftermath of the battle, Herodotus tells us, there was a

revolution at Argos, and the slaves [doûloι] seized power. Aristotle has a

different tale to relate. According to his report, the Argives were forced,

after their defeat, to accept some of their períoιkoι into the ruling order.

This may have been a matter of military necessity—for, in the aftermath of the

battle, the Lacedaemonians apparently refused to agree to the peace of extended

duration that the Argives sought. Plutarch confirms what we would in any case

surmise: that those whom Herodotus’ aristocratic Argive informants disdainfully

called doûloι outsiders would be inclined to identify as períoιkoι; and he

mentions that, because of a shortage of male citizens, the widows and young

girls of Argos married these men.

At Sparta, Cleomenes had enemies. Men who throw their weight

around, as he did, always do. And when he returned home, they tried to hoist

him on his own petard. The oracle, at his prompting, had predicted that he

would take Argos. It was presumably by announcing this that he had encouraged

the Spartans to choose war. But he had not delivered as promised, and his

enemies asserted that his failure to perform as the god had foretold was proof

that the Agiad king must have been bribed. Cleomenes was a man of exceptionally

quick wit—equal to almost any occasion—and at this time it did not fail him,

for it was by a large margin that he was acquitted in the court constituted by

the ephors and gérontes. As Cleomenes explained in court, the grove sacred to

Apollo was called the grove of Argos. It must, he told them, have been this

that the oracle had in mind—for when, as king, he had made his sacrifice at the

Argive Heraeum, he had done so with an eye to obtaining an omen favorable to a

full-scale assault on the town, and this boon he had been denied.

Later, when the word came that the Ionians had gone down to defeat at Lade and that Miletus had fallen, those at Lacedaemon attentive to the power waxing in the east must have felt a measure of consolation and relief when they contemplated Cleomenes’ accomplishment at Argos. The Agiad king may not have delivered on the oracle’s promise, but, in slaughtering the Argives on a scale unprecedented, he had done what the situation required. When the crisis came, politically divided and crippled by a lack of manpower, the Argives would not march out—against the Medes or in their support—and their neighbors in the Argolid at Tiryns, near where Cleomenes had landed and fought the battle, and at Mycenae, near the Argive Heraeum where the Agiad king had ostentatiously made sacrifice, rallied to the Panhellenic cause, as he no doubt hoped they would.

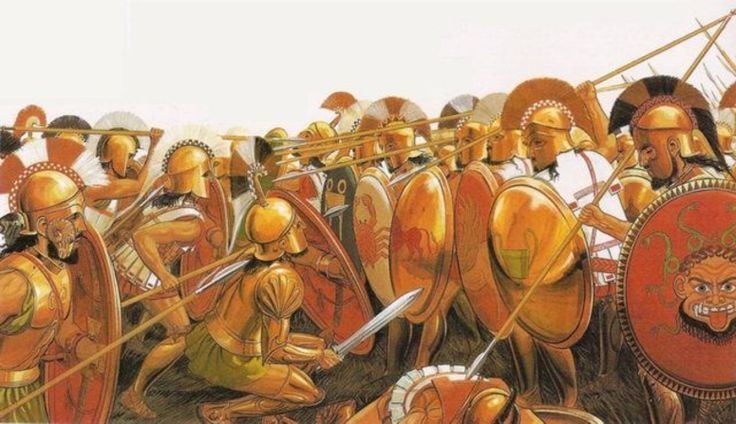

Hoplites and Phalanx Warfare Etiquette