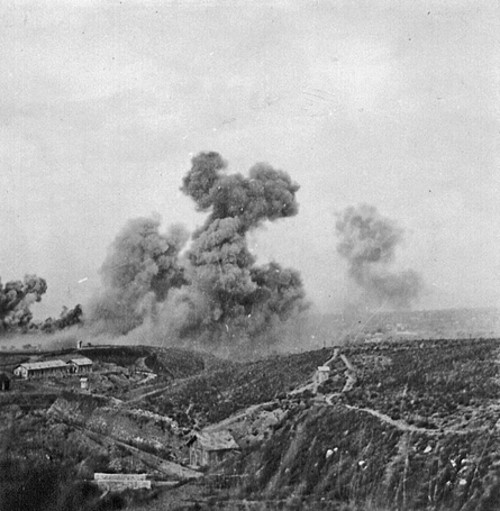

On 3 October 1943, German forces landed at Kos. Three companies of II./Gren.Rgt.16 were delayed by stiff resistance at an ‘ammunition dump’, actually a logistics camp.

That the campaign in the Aegean was a defeat is obvious and,

indeed, can hardly be denied. As the last stragglers made their slow way back

to safety, Hitler was jubilantly conferring on Lieutenant General Müller the

accolade “Conqueror of Leros” and giving his “abundant appreciation” of his

success. It must be admitted that this praise had been earned. Edwin Packer, in

his summary of the campaign, headed his conclusions “No reward for audacity,”

and in applying this to the British, he is certainly correct. For the Germans,

however, audacity had paid a handsome dividend.

Other historians, although not all, while admitting that the

British suffered a grievous setback, have sought to lessen its significance by

comparing the British and German losses on a balance sheet that sometimes comes

out equal and other times shows a marked advantage to the British. Though all

the facts will never be known precisely, it is worth examining a few of these

statements in detail in order to get a better picture.

British casualties are well tabulated. The Royal Navy lost

heavily in its final duel with the Stukas; indeed, the scale of loss is

comparable to the disaster suffered off Crete three years earlier. The cruiser

Carlisle was damaged beyond repair; six destroyers, two submarines, and ten

lesser vessels were sunk. Three cruisers were heavily damaged, as well as four

more destroyers. The Germans lost twelve small steamers and twenty minor

warships, plus one destroyer wrecked and bombed.

The Royal Air Force lost 115 aircraft, with a further 20

damaged. Luftwaffe losses in the same period have not been assessed, but one

British historian has stated that “the figures reported at the time, 135

destroyed and 126 damaged, are certainly an over-optimistic calculation.” With

the example of many other such estimates before us, we can agree that this is

probably true. Even now the enormous casualties claimed to have been inflicted

on the Germans during the Battle of Britain are still believed by many,

although the actual figures were much smaller and have been given in several

excellent works. The same will surely be found to apply in the claims and

counterclaims of the Aegean air fighting, and it seems doubtful that German

aircraft loss exceeded 120 planes.

The army had a casualty list of about 4,800, the size of an

extended infantry brigade, but many of these were taken prisoner. The list of

officers killed during the fighting on Leros makes it clear, however, that the

British suffered particularly heavily in this respect, because of the general

bravery and self-sacrifice of these men.

The fighting on Leros was particularly bloody, and the

Germans took casualties not far short of the British. In their official

communications of the time, they claimed to have taken 200 officers and 3,000

British POWs plus 350 officers and 5,350 Italians. Sixteen antiaircraft guns and

120 cannons were also captured. Their own casualties were appalling. The

paratroops in particular were cut to ribbons. As was revealed under a “TOP

SECRET” heading in the OKW Diary, the Germans suffered 1,109 casualties in

taking Leros, 41 percent of the invading force. These were not all killed, but

included the wounded. Some claims by British historians about the casualty

ratio are rather misleading. It is on record that the graves on Leros were

found to contain 1,000 Germans and 400 British, which conveys, even if

unintentionally, the impression that this was the ratio of losses in the

battle. If this were so, then it would seem that only 109 of the German

casualties were wounded as opposed to killed, which is indeed an impressive

figure. Lieutenant General Müller gave his losses for the invasions of Cos and

Leros, as 260 dead, 746 wounded, and 162 missing. The British evacuated only

177 captured Germans from Leros before it fell. However historians sympathetic

to the British cause add it up, the German number killed is less than a third

of the figure claimed at the time.

Why the great difference in calculating? Mainly because

German casualties were not separated from Italian at the time, as Churchill

adopted his usual “creative accounting.” The prime minister was well-known for

such exaggeration. Among the many examples, he stated to the House that

hundreds of German Stuka dive-bombers had been shot down during the battle of

Britain, when the true figure was just fifty-four. Earlier, when at the

Admiralty, he claimed that the Royal Navy had sunk fifty German submarines, a

totally ridiculous overestimate, when the true, verifiable figure was actually

fifteen, as proved by postwar studies; spitefully, Churchill even had the

director of antisubmarine warfare, Capt. A. G. Talbot, who dared to tell the

true figure, removed from his post.

Churchill’s figures on the Aegean casualties were never

challenged. For example, Capt. S. W. Roskill in the official history, The War at

Sea, also states in a footnote that when the Sinfra was sunk, nearly 2,000

German and Italian soldiers were lost, which is the exact figure Churchill

bragged about to Foreign Minister Anthony Eden. Though this figure is true, a

mere fraction of this total were on the opposing side. The Sinfra went down

with the loss of about 40 German soldiers out of the 500 carried; there were

also aboard some 2,000 Italians—loyal to the Badoglio government and the

Allies—and 200 Greek partisans, all of whom were being shipped back as POWs. Of

these, only about 539 Italians and 13 Greeks were saved. The prime minister’s

assertion “we drowned 2,000 of them” sounds far more impressive than “we

drowned 40 of them.” Again, more than 1,200 Italians in transit were lost

aboard the Donizetti. Clearly the deaths of British allies should not be

included in the list of German losses, and only a politician grasping at straws

would attempt to do so.

The scale of air attacks mounted by the Luftwaffe to subdue

the Leros garrison has frequently been quoted as being up to 600 missions a

day. Yet the official publication The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force,

compiled by British experts after examination of German records, completely

refutes this:

The major share of the German Air Force in the success of

both operations [Cos and Leros] stands out beyond all doubt. Yet this success

was achieved, not as has sometimes been suggested by the use of overwhelming

air power, but by fully exploiting a favorable situation with a small force

maintaining only a moderate scale of effort. Both at Cos and Leros Luftwaffe

activity was slighter than had been expected. The total effort in the two days

operations for the reduction of Cos amounted to under 300 sorties including

65–75 Me.109 sorties of a defensive character; the main weight of the attack on

October 3rd and 4th was born by Ju 87s which flew 140–150 sorties.

Of Leros, it states that operations, although very

effective, were only moderate in scale: “during the five days of attack only

676–700 offensive sorties were flown.” The Luftwaffe had, however, conducted a

softening-up campaign during the previous two months. Compare this with the

Allied effort: From October 1 to 7, the U.S. Army Air Force made a total of 425

daylight sorties against airfields, landing grounds, ports, and bases, and the

British made 63 night sorties by heavy bombers alone. From mid-October to

mid-November, when the island fell, the U.S. made 317 sorties in seven days and

the British 278 sorties on twenty-eight nights by heavy bombers. In daylight

attacks against German shipping, American Mitchells made 86 sorties and

Wellingtons and Beaufighters 11.

In addition, offensive sweeps were carried out almost daily

during the actual period of fighting on Leros. Between November 12 and 17,

Beaufighters and Mitchells made 79 sorties. Heavy bombers—American Liberators

and Mitchells and British Halifaxes and Liberators—made a total of 212 sorties

against airfields in Greece and Rhodes. Wellingtons, Hudsons, and Baltimores made

an additional 55 sorties. Spitfires with special long-range tanks and Hurricanes

made repeated sweeps over Rhodes and Crete at this time.

Particularly impressive was the record of the faithful

Dakotas of No. 216 Squadron, which had operated efficiently and constantly

throughout the campaign despite the most difficult and hazardous conditions and

some losses. From October 6 to November 19, they flew 87 sorties and dropped a

total load of 378,650 pounds. They also flew in the 120 paratroops to Cos, and

one of the most outstanding of their efforts was the dropping of 200 officers

and men of the Greek Sacred Squadron on Samos on the night of October

31–November 1. None of these troops had ever jumped before, and very few had

any experience in flying. Nevertheless, on a pitch-black night, the six Dakotas

carried out their mission with complete success. Also, all of the dispatchers

they carried were volunteer airmen and soldiers, and flying in slow transports

over German airfields packed with high-performance fighters in a round-trip of

many hours surely called for a high standard of heroism.

Much has been made of the claim that by this small effort in

the Aegean a large concentration of vital forces was drawn into the area from

more important zones. This is partially true, but not of quite the significance

that many have attached to it. Certainly the small resources of the German

maritime fleet in the Mediterranean were called on to the limit, their

shortcomings being made up from captured Italian tonnage, and the losses in proportion

to the total were large. Certainly, too, the Germans deployed aircraft from

Russia and France, but here again only on a small scale, some 150 machines in

all. The aircraft used were predominantly of obsolete types anyway, which would

have had only a limited value in the main theaters.

For example, the main air weapon, the Ju 87 dive-bomber,

although it had a brilliant war record, had been replaced by the Fw 190

fighter-bomber for ground support in the main theater of war, the Russian front,

and was mainly used as a night intruder over Western Europe toward the end of

the war. The Ju 52s, which gave such sterling service, and the Ar 196

float-plane were both low-performance aircraft and not greatly missed. The

bomber groups were soon switched back to the main fronts on termination of the

campaign, and their absence was not greatly noticed, even in Italy. Here the

Germans were able to hold with ease the Allied ground thrusts; they even

counterattacked with telling effect and managed to reinforce as well, despite

the massive effort of the heavy and medium bomber forces deployed continually

against their communications.

As for the troops employed, with the sole exception of the

Parachute Battalion, which was flown in from central Italy via Athens, all were

from regiments already in occupation of Greece and the Balkans. Not one soldier

of the Wehrmacht was otherwise pulled back from Russia or Italy. Some time

later, the islands of Cos, Leros, and Samos were handed over by Gen. Friedrich

Wilhelm Müller to Assault Division Rhodes, which became the garrison force.

Müller survived the war but was tried and sentenced to death by a Greek court

for alleged war crimes during his tenure in command on Crete and was executed

by them on May 20, 1947.

The Germans were jubilant as well as shocked at the

simplicity of their victory. According to the January 1944 issue of Das Signal

magazine:

The fighting showed especially, two facets: In the first

place, England’s sea power, which is engaged throughout the world’s seas, was

not able to successfully defend important bases in the Eastern Mediterranean

from where it had planned to put increasing pressure militarily. In the second

place, however, the quick surrender of many enemy island defenders was a

surprise. Contrary to the German soldier who, where fate puts him, fights to

the last bullet, the soldier of the Western Powers stops fighting the moment he

recognizes there is no chance to win the fight.

Failure always brings recrimination, and this campaign was

no exception. It is not the aim of this book to censure anyone, but to set out

the facts and present the arguments on each side. At the risk of

oversimplification, they can be summarized in sections. First is the issue of

Churchill versus the Americans, which is intermixed with the arguments

involving the Middle East Command and the British Chiefs of Staff. The basic

reason for the failure of the campaign was decidedly the question of air power,

which can conveniently be summarized as Tedder versus Douglas, while at the

level of the actual fighting, it was the soldier and sailor against the “brass

hats.”

Edwin Packer wrote, “The undoubted strategic advantages

which possession of the Dodecanese gave—clearly recognized by Churchill and

Hitler, though not by Marshall and Eisenhower—blinded the British into thinking

that audacity would be rewarded on this occasion as it had many times before in

the history of their country.” This is indisputably true; but it is equally

true that the Americans, though incredibly blind to the glittering prospects

offered, as it seems in retrospect, had a good case for withholding their

approval.

Captain Roskill pointed out that “we should take account of

the fact that every peripheral operation inevitably grows in size as it

progresses, with ever-increasing demands on resources; and the dislike of the

American Chiefs of Staff, and of General Eisenhower and his subordinate

commanders, for such enterprises, what time the major campaign which they had

on their hands still had to be decided, is readily understood.”

He added later a further point: “In any theatre of combined

operations there is always one position, generally an island, which, because of

its geographical position and because it possesses harbors and airfields, is the

key to control over a wide area.” As everyone realized, this key was Rhodes,

and when it was captured by the Germans it was the time for the Allies to

abandon the Aegean operation completely or recapture Rhodes first. Neither

course was adopted. The Middle East Command instead made the decision to hold

the lesser islands, but at first with the knowledge that the Germans were

preparing for the imminent occupation of Rhodes. This must be stressed. General

Maitland Wilson can hardly be blamed for embarking on the occupation of the

Dodecanese when he did, even though from the outset the odds were against him.

When he made his decision to go in, even Eisenhower was still in favor of

Accolade taking place. Following Churchill’s telegram to Eisenhower on

September 25 and Eisenhower’s reply on the twenty-sixth, in which he agreed to

spare the asked-for armored brigade and most of the shipping, the assault date

was set for October 23 by the Middle East Command. Therefore, the islands would

have had to hold out for only one month, and this at a time when the strength

and reaction of the Germans were not certain.

Nor can Maitland Wilson be blamed for the loss of Rhodes,

for he was given insufficient warning. Had he been given time to organize a

demonstration in strength as soon as the Italian capitulation was announced, it

is possible that the Germans, unaware of his true strength and expecting the

British to have been forewarned—and therefore forearmed—could have been

overawed. Certainly there would have been a better chance than that given by

withholding this vital information from Wilson until too late. As it was, only

the Germans, not the Italians or the British on the spot, were ready when the

time came. All else followed.

It was not until the unexpected fall of Cos to the Germans

that two points were made clear. First, Hitler had a deep interest in the

Aegean, and the German forces there were very much aware of its importance. And

second, this reverse had a profound effect on American thinking about the

campaign, and they thereafter began to hedge. Eisenhower certainly received

more than adequate discouragement from his superiors in Washington.

The new American viewpoint was not made clear until the Tunis Conference, and despite everything that Churchill could do to save the scheme, Accolade was finally abandoned. By this time, the British were fully committed in the islands, but they still could have cut their losses and pulled out without too much difficulty. The arguments that this would have been a difficult operation were later proved to be overly pessimistic; enough stores and troops were run in to more than justify an attempt to get the small garrison out at that time. But it was not so decided.

The outcome of the Tunis Conference and the subsequent

decisions taken by the Middle East Command are vital as to why the campaign was

pushed on to its ultimate conclusion. Prior to the conference, Portal had

telegraphed Tedder on October 7 asking him to keep an open mind on the question

of air support for Accolade. Maitland Wilson received a message from Churchill

urging him to press strongly for further support for Accolade: “It is clear

that the key to the strategic situation in the Mediterranean is expressed in

the two words ‘Storm Rhodes.”

The Joint Planners in London were expressing different opinions,

however. They felt that the Middle East Command was overestimating the

strategic importance of Rhodes; its occupation would not in itself be adequate.

They believed, as did the Americans, that further reinforcements would be

required. They recommended instead that the islands the British did hold be

evacuated.

Nevertheless, two of the principal delegates at the

conference had received promptings to the contrary from London. These

promptings, however, had little effect on the outcome, for on the evening of

October 9, Eisenhower informed Churchill of the result. In this, the prize was

agreed to be great, but those present felt that the situation that had just

developed in Italy, added to the fall of Cos, did not permit the diversion of

the forces promised earlier.

Part two of Eisenhower’s telegram is of particular interest:

“Every conclusion submitted in our report to the CCS was agreed unanimously by

all Commanders-in-Chief from both theaters. It is personally distressing to me

to have to advise against a project in which you believe so earnestly but I

feel I would not be performing my duty if I should recommend otherwise. All

Commanders-in-Chief share this attitude.”

The situation in Italy at this time was that the Germans had

shown unexpected resilience and were pouring in reinforcements at an enormous

rate. Whereas in mid-September, thirteen Allied divisions faced eighteen German

ones, by the end of October, there would be only eleven Allied against

twenty-five German. There can be little doubt then that the decision reached was

the correct one.

Tedder went even further, writing: “There was no doubt in

the mind of anyone present at this meeting that ‘Accolade’ could not now be

staged effectively. It was clear to me that the Middle East Commanders had no

faith in the project and were relieved at the decision. It was not only a

question of German reinforcements in Italy. The weather had changed decisively

for the worse.”

He cabled Portal that the question of Accolade was

considered on its merit and with great impartiality before repercussions on the

Italian campaign were examined. Maitland Wilson admitted this in a telegram

sent to Churchill. Rhodes could not be taken that year. Why then were the

British garrisons in Leros not withdrawn forthwith? Edwin Packer surmised:

“They knew the project was dear to the heart of the British Prime Minister.

Would he have thought less highly of them if they had cancelled the operation

remembering his criticism of Wavell in 1941? No one cared to put it to the

test: a reputation for caution was not a characteristic Churchill admired. So

the C-in-Cs in the Middle East decided to go on.”

Could that have been the reason? Maitland Wilson’s cable shows that other things were in their minds. As a substitute for Rhodes, why not Turkey? Again, there was a chance, as when Operation Accolade was still officially on, that if they stuck to Leros and Samos for a little longer, airfields would be made available in that country. Maitland Wilson clearly expressed this thinking: “This morning John Cunningham, Linnel and I reviewed the situation in the Aegean (Sholto Douglas was in London at this time) on the assumption that Rhodes would not take place till a later date. We came to the conclusion that the holding of Leros and Samos is not impossible, although their maintenance is going to be difficult, and will depend on continued Turkish co-operation [emphasis added]. I am going to talk to Eden about this when he arrives on Tuesday.”

Thus the straw to which they clung, in affirming that the wishes of the prime minister were to be followed as far as possible, was Turkey. There were also other considerations that influenced their decision to a greater degree than the fear of displeasing Churchill. The islands of Leros and Samos had not yet been attacked, and although the fall of Cos had shown that the Germans were determined, it was still not thought that a reinforced Leros could be assaulted successfully for some time. The illusion of “Fortress Leros” still had not been revealed and they felt that it was a bastion that, if garrisoned with good troops, could hold out against an attack. The amount of irritation that they could inflict on the scattered German garrisons on the island— and maintain until either Turkey came in or the long-deferred Accolade could be remounted in the spring—held out the promise of allowing them to hold down large German forces with a limited effort.