The aircraft that would survive the longest in the bombing

role was the Avro Vulcan. Designed to fulfil Operational Requirement 229 the aircraft

that would become the Type 698 would be designed to cover both the conventional

and nuclear bombing roles. The first prototype, VX770, undertook its maiden

flight on 30 August 1952 piloted by Wing Commander Roly Falk. The second

prototype, VX777, would join the flight test programme on 3 September 1953,

followed quite quickly by some of the early production Vulcan B1s. The crew in

all of the production versions consisted of a captain, co-pilot, navigator

radar, navigator plotter and air electronics operator. Crews would meet up at

230 OCU, first at Finningley and later at Scampton, and would eventually be

posted to flying units as a group.

Early on in the Vulcan’s career a major problem reared its

head; in level flight at high speed the aircraft showed a tendency to pitch up

and therefore much effort was expended on curing this fault. The answer was a

cranked and kinked wing plus auto stabilizers that would considerably reduce

the pitch problem; most of the fleet would either have this modification embodied

or would be delivered with it as standard. The Vulcan B1 was intended to carry

either the Yellow Sun or Red Beard free fall nuclear weapon that would be

dropped from high altitude, and to that end it was finished in gloss white

anti-flash white paint. Unfortunately, those that designed the colour scheme

forgot that dark colours on such things as national markings and the tail

numbers would absorb heat and flash from the bomb and burn through the

airframe. Also lacking in the early B1 was a dedicated ECM installation, which

was catered for by installing the ECM equipment in the bomb bay, although to

support this a turbo generator was installed to cover the electrical

requirements. Obviously, when conventional bombs were loaded the ECM equipment

had to be off loaded to make room.

Only thirty-five Vulcan B1s would be built as this version

was seen as an interim model; the B2 that would emerge in August 1958 was a far

more advanced machine. Powerplants were more powerful and the initial model was

the Olympus 200 series engine in place of the earlier Olympus 100 series

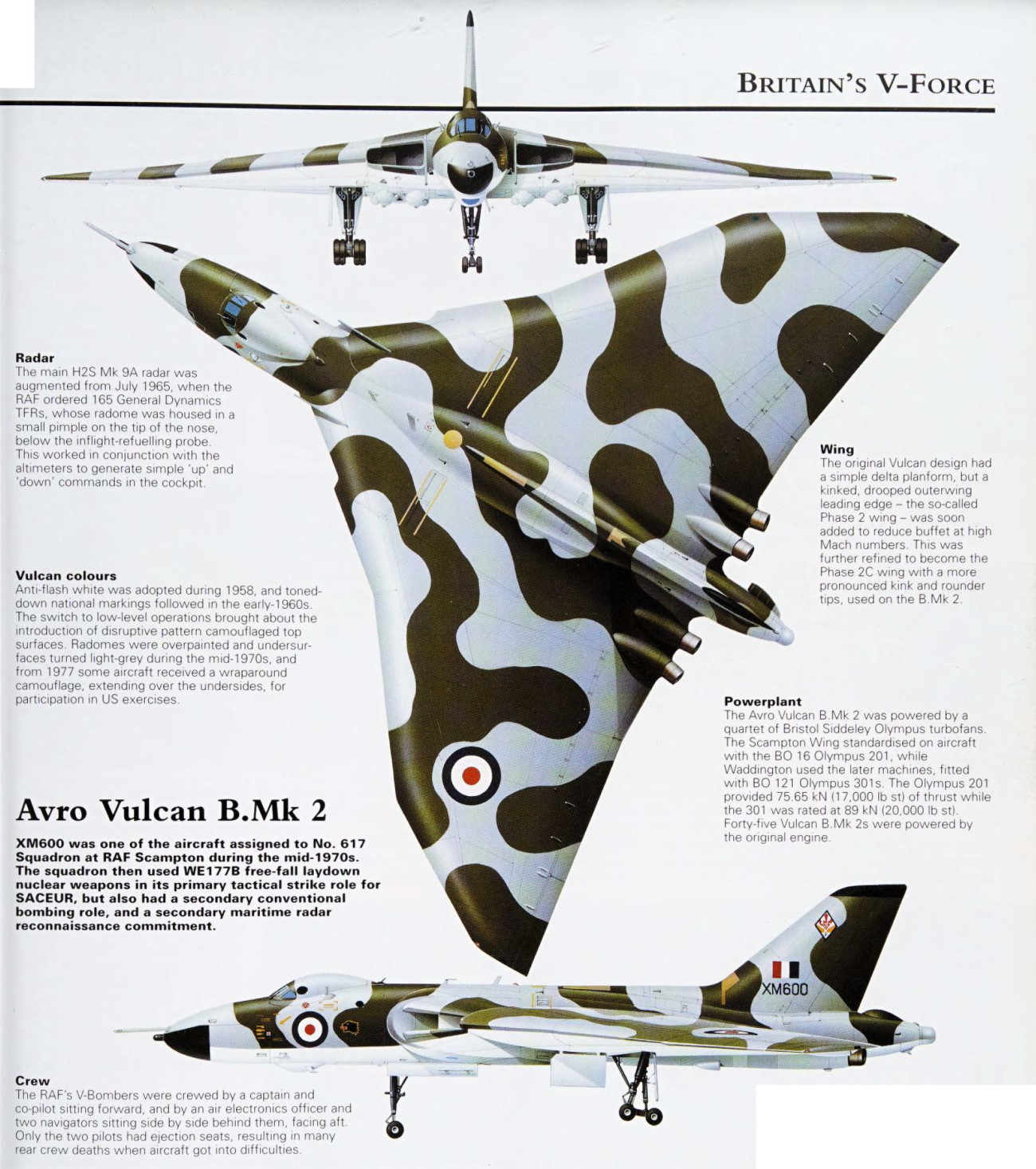

engines. The airframe also underwent significant changes; the wings had their

span extended while the leading edge was also cranked as per the earlier model.

The fuselage also underwent some changes; the ECM equipment was installed in a

purposely designed tail cone while a refuelling probe was installed in the

nose. Both of these modifications were embodied in the earlier B1s, these being

redesignated B1A after conversion. Other changes included the installation of

powered flying control units (PFCUs) for the flight control surfaces, these

being selfcontained units unlike the previous B1, which gained its power supply

from the aircraft’s hydraulics. The electrical installation also underwent a

radical overhaul being changed to 28V dc and 200v AC. This change was backed up

by the installation of a ram air turbine (RAT) and an airborne auxiliary power

plant (AAPP), both of which could supply electrical power in case of emergency;

the latter system could also supply power on the ground should no external

source be available. Initially the Vulcan B2s were delivered in anti-flash

white finish with the correct pale-coloured national markings.

Initially the B2s were slated to carry the same nuclear

weapons as the B1s, however the improvements in Soviet air defences meant that

the Vulcan fleet was more vulnerable therefore another means of delivery was

needed. The answer would be the Blue Steel standoff weapon. The project was led

by Avro whose sub contractors would provide a very capable inertial navigation

system while the powerplant was the Bristol-designed Stentor engine whose fuel

was the highly volatile hydrogen peroxide. After numerous trials at home and

Australia the first weapons were issued to No. 617 Squadron in September 1962,

although these weapons were designated for national emergency use only until

the fully developed version was available. When the decision was taken to swap

the Vulcan to the low-level role in 1964 the aircraft were repainted in upper

surface camouflage while the Blue Steel delivery tactics were altered to suit.

The Blue Steel weapon, while adequate for its purpose, was

due for replacement thus the RAF cast around for a more viable replacement. It

was during this period that the Douglas Aircraft Corporation was developing an

intermediate range ballistic missile for the USAF. Known as WS, or weapons

system, 138A the weapon was later designated AGM-87A Skybolt and was seen as a

better proposition than the Blue Steel Mk 2 as its range was far greater.

Discussion at governmental level began in 1960 with a Memorandum of

Understanding being signed on 6 June. Skybolt was beset by problems from the

beginning but each problem was cleared and each launch article behaved closer

to the desired profile. Ironically the weapon would be cancelled in November

1962 on the very day that a Skybolt performed faultlessly. To replace Skybolt

the Americans would offer the Polaris missile system as a replacement.

While Blue Steel remained in service the problem of

delivering the weapon safely at low level was becoming one of great concern as

flying into the ground with your country’s deterrent aboard was undesirable.

The answer would be the Terrain Following Radar system that was test flown

aboard XM606 during 1966. The system was housed in a small pod and was mounted

in an extreme nose just under the in flight refuelling probe.

Given the complexity of the Vulcan it was the conversion

unit that formed first, therefore in May 1956 No. 230 OCU was reformed at

Waddington to prepare for the entry into service of the Vulcan B1. The first

aircraft was officially handed over on 20 July 1956, although it was quickly

returned to Avro for further trials thus the first aircraft delivered to the

OCU didn’t turn up until September. Proper crew training finally started in

January 1957 with the first crews from A Flight being hived off to form the

basis of No. 83 Squadron. When the Vulcan B2 entered service B Flight was

formed in July 1960 to train aircrew for this version. A Flight was still in

existence flying a mix of Vulcan B1 and B1A aircraft, and this earlier model

remained with the OCU until it was retired in November 1965. The entire

organization decamped to Finningley a year later, remaining there until a final

move was made to Scampton in December 1969. By this time the OCU was flying

Vulcan B2s and the handful of Handley Page Hastings T5s used for NBS training, better

known as No. 1066 Squadron. No. 230 OCU was finally disbanded in August 1981 as

there was no further need for Vulcan crews as the force was winding down.

The first operational unit to form with the Vulcan B1 was

No. 83 Squadron based at Waddington whose first aircraft arrived in July. As

the first operational unit No. 83 Squadron found itself heavily involved in

developing tactics for the new aircraft and proving that it was more than

capable of doing the job it was designed for. Once fully operational the

squadron was declared as part of Britain’s nuclear deterrent. Initially the

Vulcans were configured to deliver Blue Danubes, although these were later

replaced by Violet Clubs.

In 1960 No. 83 Squadron moved to Scampton minus its Vulcan

B1s in order to prepare for the Vulcan B2. By October the squadron was declared

operational on its new mount, although its primary role initially was that of

free fall weapons delivery both in the strike and attack modes. By 1963 the

squadron’s role changed to that of Blue Steel delivery and the unit remained in

this role until being disbanded in August 1969.

Hard on the heels of No. 83 Squadron would be No. 101

Squadron, which would trade in its Canberra bombers for the Vulcan B1. Based at

Finningley the unit reformed as a Vulcan operator in October 1957. After being

declared operational the unit undertook numerous detachments, the most notable

of which was to South America during May 1960. By March 1961 the Vulcan B1s

were being replaced by the more capable B1A. With the new model in service the

squadron moved to Waddington and undertook training to deliver the Yellow Sun

nuclear weapon in the free fall role. The squadron would receive its first

Vulcan B2 during 1967 and would retain the model until disbanding in August

1982 having provided crews for the recapture of the Falklands.

Possibly the best known bomber squadron was No. 617

‘Dambusters’ Squadron, which traded in its Canberras and reformed with the

Vulcan B1 at Scampton in May 1958. By September 1960 the squadron was equipped

with the Vulcan B1A, although these were dispensed with in August 1961 being

transferred to Waddington to equip No. 50 Squadron while No. 617 Squadron

received the Vulcan B2 as replacements. This squadron would also be equipped to

carry the Blue Steel standoff missile and retained this role until the weapon

was retired in favour of Polaris. With their aircraft restored to the free fall

role No. 617 Squadron trained for the strike mission with the WE177B nuclear

free fall weapon while in the attack role the aircraft was used to drop a

variety of high-explosive bombs.

One other unit (No. 83 Squadron) also flew from Scampton

with the Vulcan B2, reforming in April 1961. Initially deployed in the free

fall role the unit flew with Blue Steel rounds aboard until the weapon was

retired, after which the squadron returned to the free fall role until

disbanded in March 1972.

Over at Waddington two units would form to fly the Vulcan

B1, the first was No. 44 Squadron, which was basically the original No. 83

Squadron renumbered. By July 1961 the unit was equipped with Vulcan B1As,

retaining these plus the Yellow Sun free fall weapon until 1967 when the B2 was

received. By this time the Vulcan squadrons were learning about flying at low

level, although the bomber still needed to make a rapid climb to 12,000 feet to

release the weapon. No. 44 Squadron finally disbanded at Waddington in December

1982. Also at Waddington was No. 50 Squadron, which gained its Vulcan mix from

No. 617 Squadron in August 1961 and had already adapted to low-level operations

in 1964 before the Vulcan B2 arrived in December 1965. The squadron used its

aircraft in both the free fall strike and attack roles before changing its role

completely in 1982 when six aircraft were converted to single point tankers.

No. 50 Squadron disbanded in March 1984.

Coningsby would be the home for the final three Vulcan

operational units. No. 9 Squadron would receive its Vulcan B2s in March 1962,

although the entire wing decamped to Cottesmore in November 1964. Initially the

squadron was trained to deliver the Yellow Sun free fall nuclear weapon,

although this was replaced later by the WE.177B weapon. When the strike task

ended for the Cottesmore Wing No. 9 Squadron was dispatched to Akrotiri as part

of the NEAF Strike Wing. Also at Coningsby and later Cottesmore was No. 12

Squadron whose operational history with the Vulcan B2 was similar to that of

No. 9 Squadron. When Polaris became part of Britain’s nuclear deterrent No. 12

Squadron was disbanded in December 1967 and later reformed as a Buccaneer unit

in October 1969. The final Coningsby/ Cottesmore wing unit was No. 35 Squadron,

which received its aircraft in December 1962. In common with the two other

units No. 35 Squadron trained on both the Yellow Sun and WE.177B free fall

nuclear weapons before transferring to Akrotiri as part of the NEAF Strike

Wing. The Vulcan would also be operated by other units in various roles. The

Bomber Command Development Unit was the main one. Based initially at Wittering

the unit originally covered the Canberra before taking on the Valiant. After a

move to Finningley the BCDU concentrated its efforts on the Vulcan and remained

active until December 1968.

The final member of the V bomber triumvirate to join the RAF

would be the Handley Page Victor. Beaten into the air by the Vulcan prototype

that flew on 30 August 1952 those building the Victor had to wait until

Christmas Eve to get their contender into the skies. Although the Victor prototypes

performed within design specifications there were a few design miscalculations

that eventually led to the loss of WB771 on 14 July 1954, when the tailplane

detached whilst making a low-level pass over the runway at Cranfield. This

caused the aircraft to crash with the loss of the crew. The tailplane was

attached to the fin using three bolts thus more stress than had been

anticipated was generated and the three bolts failed due to metal fatigue. Also

adding to the loading problems the aircraft were tail heavy due to the lack of

equipment in the nose, although this was remedied by placing large ballast

weights in that area. The fin on production aircraft was shortened to eliminate

the potential for flutter while the tailplane attachment was changed to a

stronger four-bolt fixing arrangement.

The first prototype Victor B2, serial number XH668,

undertook its maiden flight on 20 February 1959. The aircraft had flown 100

hours quite safely when on 20 August 1959 while undertaking high-altitude

engine tests for the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment it

disappeared from radar screens and crashed into the sea off the coast of

Pembrokeshire. An extensive search operation was initiated to locate the

aircraft and the wreckage was finally discovered in November 1960 with the

accident investigation report concluding that the starboard pitot head had

failed during the flight, causing the aircraft’s flight control system to force

the aircraft into an unrecoverable dive. Only minor changes were needed to

resolve this problem thus allowing the Victor B2 to enter service in February

1962.

A total of twenty-one B2 aircraft were upgraded to the B2

Blue Steel standard with Conway engines of increased thrust while fitments were

incorporated to allow the carriage of a Blue Steel standoff nuclear missile.

The aircraft’s wings were modified to incorporate two pods or Küchemann carrots

that were anti-shock bodies that reduced wave drag at transonic speeds. They

were also used as a convenient place to house chaff dispensers. Handley Page

proposed building a further refined Phase 6 Victor with more fuel and the

capability of carrying up to four Skybolt ballistic missiles on standing

airborne patrols, although this proposal was later rejected. Later it was

agreed that some of the Victor B2s on order would be fitted to carry two

Skybolts, although this idea was later abandoned when the United States

cancelled the whole Skybolt programme in 1963. With the move to low-level

penetration attack profiles the Victors were fitted with air-to-air refuelling

probes above the cockpit, large underwing fuel tanks receiving a two tone

camouflage finish in place of the original anti-flash white. Trials were also

conducted with terrain-following radar and a side scan mode for the bombing and

navigation radar but neither became operational.

Nine B2 aircraft were converted for strategic reconnaissance

purposes as the SR2 to replace the Valiants that had been withdrawn due to wing

fatigue, with delivery beginning in July 1965. They received the capability for

a bomb bay camera crate or a bomb bay-mounted radar mapping system plus air

sniffers mounted at the front of the under wing tanks to detect particles

released after nuclear testing. The long-range photographic reconnaissance role

for the Handley Page Victor began in 1964 when Victor B2 XL165 became the

prototype for the Victor B(SR)2, this later being changed to SR2. XL165

undertook its maiden flight in February 1965 with deliveries of the aircraft

beginning in May to No. 543 Squadron at RAF Wyton. The squadron undertook

reconnaissance missions sorties far and wide, also carrying out high-level

survey photographs for various governments. It was said that one Victor SR2 could

photograph the whole of the UK in a single two-hour sortie.

The withdrawal of the Valiant fleet due to metal fatigue in

December 1964 saw the RAF with no front-line tanker aircraft and with the B1/1A

aircraft now judged to be surplus in the strategic bomber role they were

refitted for this duty. To get some tankers into service as quickly as possible

Handley Page converted six B1A aircraft to B(K)1A standard, although these were

later redesignated B1A (K2P). The version received a two-point system with a

hose and drogue carried under each wing while the bomb bay remained available

for weapons. Handley Page worked day and night to convert these six aircraft

with the first being delivered on 28 April 1965, and No. 55 Squadron becoming

operational in the tanker role in August 1965. While these six aircraft

provided a limited tanker capability suitable for refuelling fighters, the Mk

20A wing hose reels could only deliver fuel at a limited rate therefore they

were not suitable for refuelling larger aircraft. Work therefore continued to

produce a definitive three-point tanker conversion of the Victor Mk 1. Fourteen

further B1As and eleven B1s were fitted with two permanently fitted fuel tanks

in the bomb bay plus a high-capacity Mk 17 centreline hose unit with three

times the fuel flow rate as the wing pods, these being designated K1A and K1

respectively. The remaining B2 aircraft were not as suited to the low-level

strike mission as the Vulcan with its strong delta wing. This, combined with

the change of the nuclear deterrent from the RAF to the Royal Navy using

submarine launched Polaris missiles meant that the Victor B2s were now surplus

to requirements. Therefore twenty-four B2s were modified to K2 standard.

Similar to the earlier K1/1A conversions the wingspan was reduced to reduce

stress while the nose glazing was plated over.

The Victor was the last of the V bombers to enter service

with the first deliveries of B1s to No. 232 Operational Conversion Unit RAF

based at RAF Gaydon before the end of 1957. The first operational bomber

squadron, No. 10 Squadron, formed at RAF Cottesmore in April 1958 while a

second squadron, No. 15 Squadron, formed before the end of the year. Four

Victors, fitted with Yellow Astor reconnaissance radar, together with a number

of passive sensors, were used to equip a secretive unit, the Radar Reconnaissance

Flight at RAF Wyton. The Victor bomber force continued to increase with No. 57

Squadron forming in March 1959 while No. 55 Squadron formed in October 1960.

Deliveries of the improved Victor B2 started in 1961, with

the first B2 Squadron, No. 139 Squadron forming in February 1962 with a second,

No. 100 Squadron, forming in May 1962. These were the only two bomber squadrons

to form on the B2, as the last twenty-eight Victors on order were cancelled.

The prospect of Skybolt ballistic missiles, with which each V-bomber could

strike at two separate targets, meant that fewer bombers would be needed, while

the government were unhappy with Sir Frederick Handley Page’s resistance to

their pressure to merge his company with competitors. In 1964–1965 a series of

detachments of Victor B1As was deployed to RAF Tengah, Singapore, as a

deterrent against Indonesia during the Borneo conflict. The detachments

fulfilled a strategic deterrent role as part of Far East Air Force, while also

giving valuable training in low-level flight and visual bombing. In September

1964, with the confrontation with Indonesia reaching a peak, the detachment of

four Victors was prepared for a rapid scramble with two aircraft loaded with

live conventional bombs and held at one-hour readiness, however they were not

required to fly combat missions therefore the readiness alert finished at the

end of the month.

With the Victor B2 fleet now redundant Handley Page prepared

a modification scheme that would see the Victors fitted with tip tanks, the

structure modified to limit further fatigue cracking in the wings and ejection

seats provided for all crew members. The Ministry of Defence delayed signing

the order for conversion of the B2s until after Handley Page went into

liquidation. The contract for conversion was instead awarded to Hawker Siddeley

who produced a much simpler conversion than that planned by Handley Page, with

the wingspan shortened to reduce wing-bending stress and thus extending

airframe life.

An accident review for 1959 covering all three V bombers

revealed some disturbing trends. As the first to enter service the Valiant

fleet had seen its losses and major incident rates drop as experience was

gained. During 1955 WP211 had experienced a rough running No. 3 engine; this

had then been shut down at which point the fire warning light had illuminated.

The Graviner fire bottles for the engine were then fired, which in turn caused

the warning light to go out. After landing safely No. 3 engine was inspected

and the failure of a compressor seal was discovered as the source of the fire.

A similar set of circumstances befell WP212, which landed back at base after

the No. 1 engine compressor seal had failed. Less lucky were the crew of WP222.

Having departed for a cross country flight the aircraft was seen to turn to

port instead of starboard as expected. Although the crew were obviously

attempting to correct the bank the nose continued to turn towards the ground.

The entrance door was jettisoned and the signaller baled out, although he did not

survive. The Valiant continued towards the ground at a speed of 300 knots

before crashing and killing the remaining crew members. The cause was

determined to be either a stuck switch or a runaway actuator. Modification

covering both of these faults was quickly carried out while the remaining

Valiants were inspected and repaired as needed. One of the most telling

incidents occurred on 29 April 1957 to Valiant WB215, which was being used by

the Ministry of Supply. The aircraft was tasked to undertake Super Sprite

rocket trials. During a run of the drop range the pilot banked away during

which a lurch and muffled bangs were felt and heard. Although the crew

suspected a problem they carefully nursed the aircraft back to base at which a

normal landing was made. Post flight inspection revealed that the starboard

mainplane rear spar near the wing break joint had failed close to the

undercarriage bay.

The Vulcan also had its fair share of incidents, some of

which were almighty cock-ups. The greatest of these involved B1 XA902, which

was cleared to land on a runway that was bordered by snow banks. After

touchdown the brake parachute was deployed, followed by a wild swing into one

snow bank and a collision with the other bank. The result of this collision was

the collapse of the port undercarriage and sideways slide off the runway. The

subsequent investigation criticized the uncleared runway, the lack of proper

self briefing by the crew and a failure by the Air Ministry to adequately

provision major airfields with enough snow-clearing equipment.

Possibly one of the most serious incidents to overtake the

Victor in its early years happened on 16 April 1958 when XA921 was undertaking

trials for the Ministry of Supply. The crew were briefed to undertake bomb door

and store release trials at various heights and speeds. During one of these

bomb door cycles the installed close circuit television switched off, and the

crew opted to return to base. During the post-flight inspection it was

discovered that the rear bomb bay bulkhead had completely collapsed, which in

turn had caused the false bulkhead at frame 804 to break up and the debris

entered the bomb bay causing damage to the hydraulic and electrical systems in

the bomb bay. All in-service Victors were then issued with an in-flight

restriction concerning bomb door opening, although this was subsequently

cancelled by Modification 943 being applied to all the extant aircraft.