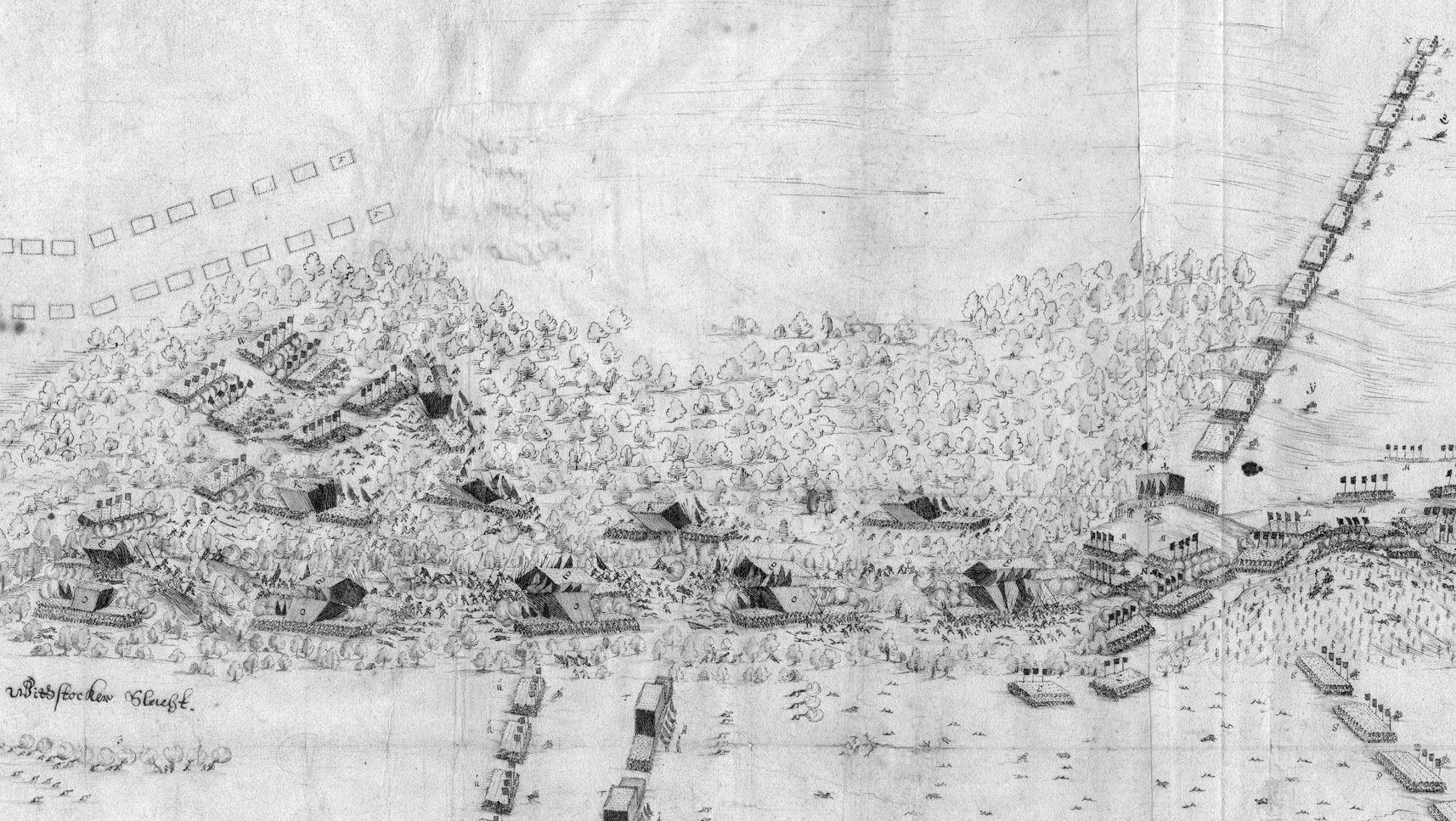

The Battle of Wittstock. The Swedish army prepares for

its assault on the wood defenses of the Allied center and left flank before

Wittstock.

Initial Swedish attack and Imperial realignment.

Swedish breakthrough and Imperial retreat.

The Battle of Wittstock Scholars cannot agree on the size of

the two contesting armies that met at Scharfenberg outside Wittstock in October

1636. Some reports allow the Imperialists only 12,000 men while allocating the

Swedish force 22,000. More usually the Swedes are estimated at just over 15,000

and the Imperialists at 22,000, although various other statistics are also

postulated between these ranges. Peter Wil- son, following the lead of Hans Delbrück,

has opted simply to conclude that the two sides were `fairly even in numbers’.

The discrepancies arise, in part, due to an over-reliance on a rather limited

selection of the available battlefield reports wherein the voices of two of the

four most senior commanders on the Swedish side that day – Alexander Leslie and

James King – have largely been overlooked. Rather, there has been a preference

to seek authority in the scholarship of Hans Delbrück, who missed these reports

and instead repeated the assessment of pro-Imperialist contemporaries as

interpreted by another scholar, Rudolph Schmidt. The cumulative result of

continued repetition has been to produce only a partial and confused appraisal

which misses some crucial detail of the battle. Secondary literature concerning

Wittstock frequently fails to consider the role of anyone on the Swedish side

other than Torstensson and Banér, and they actually served together in the same

wing of the army. For example, Delbrück mistakenly placed Leslie in charge only

of the `reinforcements’ of 4,000 men rather than in command of the centre of

the army, and even this only appears in a note, not the main text. Classic

accounts of the war, such as that by C. V. Wedgewood, mention Leslie in a more

meaningful way, but often out of position: she locates him on the flank, as if

Banér’s troops formed the centre. Other errors have crept in: T. M. Barker

conflates Major General John Ruthven (second in command of the reserve) with

his uncle, Patrick Ruthven, who we know was in Scotland on a recruiting

mission. Scandinavian scholars have traditionally paid more attention to the

role of the Scottish commanders at Wittstock, albeit the lack of attention to

the Scottish accounts, or even close scrutiny of Banér’s, has led to errors. In

one account of the battle the left flank was correctly placed under the Finn

Torsten Stålhandske and the Scot James King but missed the important caveat

that King was the senior officer. Furthermore, Leslie’s role – or indeed that

of the entire centre of the Swedish army – is usually altogether absent. Analysis

of the reports of the Scottish generals is crucial to understanding this

battle, let alone the significant role the Scottish military commanders played

within it. Interestingly, the Scots were not simply distributed within the main

infantry battalions of the Army of the Weser, but across every single section

of the army, and with some astonishing results.

When the Banér-Leslie army formed up on the morning of

Saturday, 4 October 1636, it was divided into four distinct sections, each one

with a clearly assigned role. Banér (seconded by General of Artillery

Torstensson) and 3,500 men took up position on the right wing of the army,

directly facing Johan Georg of Saxony. His wing (the smallest of the four

sections) comprised seventeen squadrons of cavalry, some reputedly commanded by

Colonel David Leslie, backed by 700 musketeers led by the Scottish Catholic

Colonel William Gunn. 103 Field Marshal Alexander Leslie took command of the

centre (seconded by Major General Thomas Kerr), directly in front of Hatzfeldt’s

Imperial Army. He had five brigades of infantry and five cavalry squadrons

amounting to 4,342 men. Lieutenant General James King’s cavalry (seconded by

Major General Torsten Stålhandske) formed the left wing with some eighteen

cavalry squadrons, two of which were commanded by Colonel Robert Douglas.

Command of the reserve fell to Lieutenant General Johan Vitzthum (seconded by

Major General John Ruthven), with the largest single contingent comprising

4,656 men divided into four brigades and twelve cavalry squadrons. The plan was

audacious: King’s cavalry were sent on a sweeping flanking manoeuvre to the

west with the purpose of circumnavigating enemy positions and surprising them

at the rear. As a distraction Banér hoped to keep the enemy busy with a head-on

assault on the Saxon positions supported by fire from Torstensson’s artillery

and Gunn’s musketeers. Leslie, with the infantry brigades, was to feign an

attack on the main Imperial centre and thus prevent them from supporting Johan

Georg’s forces. Cumulatively it was hoped that Banér’s men would break the

Saxons, who would then be forced straight into the path of King’s cavalry,

which would, all being well, be approaching the Imperial rear from the west.

However, all did not go to plan, and it is here that the reports start to

differ.

Banér’s phalanx found the Saxon troops to be steadfast, and

he reported there was not one of his squadrons that did not have to engage them

at least six times, and some as many as ten. The attacks were so ferocious that

Banér’s forces began to waver. The Swede blamed this on the slow movement of

King’s cavalry in traversing the difficult swamps and woodlands to the west of

the battlefield, while the reserve was similarly slow to enter the fray. What

happened next is crucial: not only was Leslie contending with Hatzfeldt’s

forces directly in front of him, but he was now forced, in addition, to

intervene in support of the wavering right flank, requiring him to traverse the

battlefield. As Banér informed Queen Christina, his own troops were in trouble:

auch weren wegen der grosen force des feindes in eine

gentzliche disorder gekommen, wan nicht der Feltmarschalch Lessle mit 5

brigaden zu fuss, die er in der battaglia bey sich gehabt, unss eben zu rechter

zeit secundiret undt 4 brigaden von des feindes infanteria, die sich allbereit

auch auf unss gewendet, undt unss in die flancke gehen wollen mit menlichen

angriff poussiret undt von unss abgekeret, das wir etzlicher- massen zu

respiration kommen können.

(due to the strength of the enemy they would have fallen

into total disorder, if Field Marshal Leslie with the five brigades of foot

which he had with him during the battle had not assisted us just in time and

had not manfully attacked and turned away from us four brigades of the enemy’s

infantry . so that we could finally gain our breath.)

That Leslie’s battalions served as the salvation of Banér’s

wing has been picked up in some histories, even if it is not more generally

understood by scholars of the war. 108 Given the availability of Banér’s

account, in print for over a century, it is perhaps surprising. Nonetheless,

Leslie’s actions were widely reported at the time. As William Boswell, an

English diplomat in The Hague, put it:

These p[ar]ticulars are grownded upon l[ett]res from

Banier’s Army unto ye French Resid[en]t who sent this Expresse; and the Report

of the Expresse himselfe who was in the Fight & an Eye-witnesse of what

passed: One circumstance is added w[hi]ch I can not omitte, That a part of

Banier’s owne forces, being overlay’d so farre, as they began to thinke how to

save themselves, by a retreate; (and had given back; but that) Lesley coming in

to their succour, put the Ennemy first to flight, w[hi]ch they could never

recover.

As stated above, Leslie’s role at Wittstock is not totally

unfamiliar to scholars approaching the subject from a Swedish perspective.

However, it is in trying to understand the full contribution of the Scottish

troops that serious discrepancies occur even in contemporary accounts. In

particular, the role of King’s left wing and the flanking manoeuvre it carried

out, which proved so influential in the battle, has often been misrepresented.

Not only was command erroneously assigned to the more junior Stålhandske by

historians, but even contemporary errors, such as Banér’s explicit statement

that the late arrival of King’s horse caused his forces distress, have been

blindly repeated. In addition, Banér’s claim that King’s forces actually had

little to do on the first day of the battle has cast doubt on King’s

contribution to the outcome of the battle. King’s own report, however,

unambiguously states that it was the appearance of his cavalry in combination

with Leslie’s infantry support for Banér that provoked the enemy’s initial

retreat and thus led to the eventual Swedish breakthrough. Rather than having

`little to do’ on the first day of battle, King’s report reveals that despite

Banér’s orders to cease action as night drew in, two of King’s regiments

(commanded by Stålhandske) advanced and destroyed three of the enemy’s

regiments. King further claimed that Banér’s reluctance to allow his cavalry to

pursue the enemy into the night permitted the Imperial troops to escape. It is

not only King’s report which casts doubt on some of Banér’s attempts to

downplay the role of other commanders at the battle, or which adds new

dimensions to the actions on the day.

Field Marshal Leslie’s two extant reports of the battle were

both written three days after the event and include an official report for the

Swedish government, and a second relation to his long-time friend Axel

Oxenstierna. The Leslie and King accounts reinforce our understanding of the

extent of Scottish military command on the battlefield and perhaps bring the

`trust element’ brought out by the kith and kin relations of Scots more fully

into view. The Scottish commanders amounted to a field marshal (Leslie), a

lieutenant general (King) and two major generals (Thomas Kerr and John

Ruthven). We now also know of no less than eleven brigades or squadrons under

Scottish command at the battle and can identify over fifty officers spread

throughout the army. Strangely, or perhaps deliberately, elements of the Army

of the Weser and other Scottish colonels were found in each of the four

sections of the combined Swedish army rather than serving together in a single

unit. This is suggestive that Leslie wanted to ensure he had people he could

trust in each quarter. Thus, while Banér’s relation high- lights how much of

the audacious plan was his, and how much he suffered in gaining the victory,

one senses that Leslie and King had far more to do with the conception and

execution of tactics than Banér allows.

A really striking piece of information found in the King and

Leslie reports, but missing from Banér’s, is mention of Major General John

Ruthven. Both King and Leslie place Ruthven as co-commander of the main reserve

under Lieutenant General Johan Vitzthum. His deployment in this position is

interesting, not least as his very presence on the battlefield usually goes

unnoticed. Ruthven had served under Leslie as a company commander during the

1628 Stralsund operation and had been in the Army of the Weser for most of

1636. Furthermore, having married Leslie’s daughter Barbara sometime before May

1631, Ruthven was not just a trusted colleague but also the field marshal’s

close kinsman. Indeed, Leslie had several kinsmen on the field, including his

son, Colonel Alexander Leslie. One can only view Leslie’s deployment of his

kith and kin at Wittstock as evidence of his implicit trust in those

individuals. Vitzthum, in contrast, had already acquired something of a

reputation for being `slow’ to commit to actions and of unreliable

trustworthiness. When Banér found himself struggling on the right flank at

Wittstock, he sent orders that Vitzthum should commit the reserve to battle.

Vitzthum refused not only these but also similar instructions sent by Leslie,

allegedly fearing the day would turn into another defeat like Nördlingen. In

the Swedish Riksråd it was later reported that Vitzthum’s men had eventually

advanced against his orders, and we can reason- ably assume that they were

ordered forward by his second in command, Major General John Ruthven. Vitzthum

later faced allegations of treason for this, for his quip about Nördlingen (a

comment unbefitting of a general) and for a series of other dubious actions.

Despite this he managed to leave Swedish service in favour of serving the

emperor without being prosecuted. As the surviving ordre de bataille

highlights, Leslie not only had a major general from his Army of the Weser in

the reserve, but his son-in-law, Ruthven, was also in position with two chosen

units placed, rather skilfully, on either side of Vitzthum himself, and in one

diagram with another (Thomas Thomson’s) directly behind the German commander –

almost as if to cater for the eventuality that Vitzthum’s nerves would fail.

Thomson, it should be remembered, was an old veteran of Leslie’s Närke och

Varmland, the very same regiment he now commanded. Whether the placing of

Ruthven and Thomson was accidental or deliberate, Banér’s report merely states

that Vitzthum’s men reinforced `the anguish of the right’ by arriving too late

to fight. Given the reports that Vitzthum’s subordinates acted in spite of

their commander, the implications for Ruthven as surrogate commander of the

reserve, and Thomson as his second, are obvious. Furthermore, Vitzthum’s

dereliction of duty meant that during the battle itself, three of the four

sections of the Swedish army (centre, left wing and by default, the reserve)

were actually under Scottish command, and Banér himself ascribed the final

victory to their actions, particularly Leslie, and even (if grudgingly) to

King’s left wing and Ruthven’s reserve.

The reports from the Scottish commanders agree with the

existing orthodoxy concerning the battle in two regards. Firstly, they support

the notion that the Swedes were outnumbered, explicitly stated by both Leslie

and Banér, and secondly, they reiterate the human dimension to the victory.

Wittstock cost thousands of lives on all sides. Again statistics vary, but it

is generally agreed that somewhere between 7,000 and 10,000 men died that day

with many more injured and invalided, including numerous Scots in the ranks and

among the officers. Indeed, the most senior Swedish commander killed, and

mentioned in all the main reports, was Colonel Robert Cunningham, while one of

the two brigades reported as `virtually destroyed’ included the men under Major

General Thomas Kerr’s command – the Karrische brigade. Lieutenant Colonel John

Lichton was also among the slain while Colonel William Gunn was noted as among

the seriously wounded, his personal squadron being reduced by over half of its

officers and men. In the process both survivors and fallen had participated in

a stunning victory, which several scholars over the years have compared to

Hannibal’s victory over the Romans at Cannae in 216 bc. John Durie, writing

from Stockholm within days of the battle, commented that:

As for the publicke newes, It is certaine y: t the Saxon

& Imperiall forces are quite defeated in Pomenn by Bannier & Leslie,

this victory is counted as considerable as any w: ch hitherto they have gotten.

For it was a general battaile of all forces on all sides & ye defeate of ye

enemy is total of all ye Infantry, and of soe many of ye horse as did not

escape by flight. On Sunday next they will shoote all ye ordnance here about ye

towne in signe of ioy.

The victory at Wittstock put the Swedes back on the map as a

serious military force and removed Elector Georg Wilhelm of Brandenburg as a

significant player in the war. It had the additional effect of ensuring the

Imperialists had to recall troops from their campaigns against the French,

thereby relieving Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar. But all was not as well in the

Swedish camp as one might expect.

For all the positive reports of the battle, the very real

tensions simmering between Banér and Leslie soon became apparent. Leslie’s account

of Wittstock to Oxenstierna contains a striking additional clause missing from

the one sent to Queen Christina. In it, Leslie mounts something of an assault

on some of his fellow commanders within the Swedish hierarchy. As Leslie put

it:

Wiewohl ich nicht daran zweiffle, von meinen übell

affectionirten Ew. Excell. anderst hinderbracht sein möchtten, so ist doch Gott

bekant, dass (ich) dahin allewege meinen scopum dirigirt, damit Ew. Excell. in

meinen sachen ein satsames und wohlgefelliges genugen thun möchte. Versehe mich

auch disfals meine actiones remonstriren und meine missgönnern widersprechen

werden, und wünsche, dass mit Ew. Excell. in disser sachen mundliche

underredung pflegen könte, wie den verhof- fendlich die zeit geben wird.

(Although I do not doubt that those who are viciously

affected towards me will have told Your Excellency differently, God knows that

I have always directed my actions in order that Your Excellency may have had an

ample and complete satisfaction regarding those things which concern me. I

hope, that if this is the case, my actions will remonstrate and contradict

those who envy me, and I wish that I could talk with Your Excellency about this

matter. Time will hopefully grant this.)

From the various accounts already discussed, it is clear

that when Leslie dis- cussed `those viciously inclined’ towards him within the

Swedish forces he must have been including Johan Banér. He also indicated that

he wished now to be decommissioned from Swedish service, again in contradiction

to Banér’s understanding of Leslie’s position. Within months, James King also

told Oxenstierna it was time for him to leave Swedish service and inferred that

Oxenstierna knew why. It is perhaps of interest that Alexander Erskine, the

Scotsman who was serving as a secret Swedish war councillor and commissioner in

Banér’s army, also chose this moment to seek release from Swedish service –

largely due to his personal difficulties with Banér.