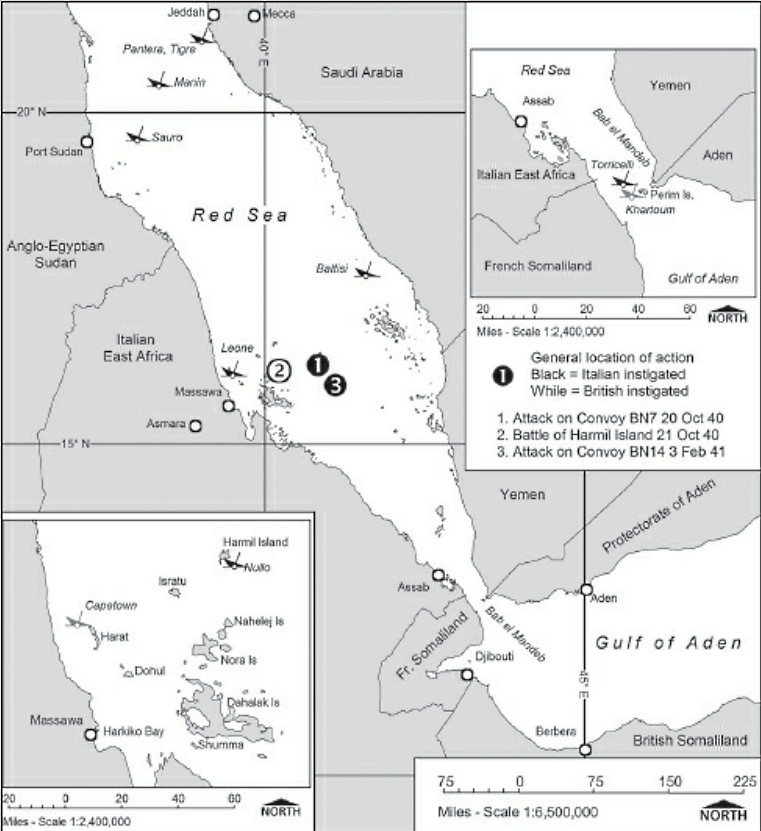

The Red Sea, 1940–1941

Long months of torture in the blazing heat and incredible

humidity of Massawa had left us apathetic and drained of hope of escape.

—Edward Ellsberg, No Banners No Bugles

Italy’s East African possessions, particularly its Red Sea

base at Massawa, were situated strategically astride the sea route to Suez.

With the Sicilian Channel closed to normal transit, Italy theoretically

possessed the ability to block maritime access to Egypt.

Between 1935 and 1940 Italy’s planners envisioned the

construction of an oceanic fleet that, in its most realistic version, would

have consisted of two cruisers, eight destroyers, and twelve submarines, all

fitted for tropical service and supported by a network of bases along Italian

Somaliland’s Indian Ocean coast. However, this Flotta d’evasione proved more

than Rome could afford. Thus, Rear Admiral Carlo Balsamo, who commanded Italy’s

East African naval squadron, deployed eight modern submarines, seven

middle-aged destroyers, two old torpedo boats, five World War I–era MAS boats,

and a large colonial sloop, all concentrated at Massawa. In Supermarina’s view,

the squadron’s limited stocks of fuel and ammunition restricted its role to one

of survival and sea denial, relying mainly upon the submarines, for the

duration of a six-month war.

Great Britain intercepted Italy’s 19 May orders for the

“immediate and secret mobilization of the army and air force in east Africa,”

whereupon the Royal Navy reinforced its Rea Sea Squadron, which consisted of

the Dominion light cruisers Leander and Hobart, the old antiaircraft cruiser

Carlisle, three sloops, and four ships of the 28th Destroyer Flotilla. This

force was tasked with preventing Italian reinforcements, engaging the Massawa

squadron, blockading the coast of Italian Somaliland, and protecting the

shipping lanes to Suez and Aden.

On 10 June Italy’s Red Sea submarines occupied, or were on

their way to, their patrol stations, but their forewarned enemy had already

halted all mercantile shipping to the Red Sea on 24 May. They enjoyed only one

success, when Galilei sank the Norwegian tanker James Stove (8,215 GRT) on 16

June. In exchange the Italians lost four boats. Crew poisoning caused by the

release of methyl chloride, used as a cheap substitute for freon in the

air-conditioning system (a defect that inadequate testing and training under

realistic battle conditions failed to reveal), led to the stranding and

wrecking of Macallé on 15 June. Galilei attempted to fight it out on the

surface with the 650-ton trawler Moonstone on 19 June, but two well-aimed

shells from the auxiliary’s 4-inch gun killed Galilei’s captain and all the

officers except a midshipman. A British boarding party captured the submarine

and a set of operational orders. These enabled the sloop Falmouth to track down

and sink Galvani in the Persian Gulf on 24 June. The same intelligence led to

the interception of Torricelli, the fourth Red Sea submarine lost in the war’s

first fortnight.

Destroyers Kandahar, Kingston, and Khartoum, along with sloops Shoreham and Indus, intercepted Torricelli north of Perim Island, at the entrance to the Red Sea, at 0418 on 23 June. The Italian submarine, initially seeing only one sloop, and considering her damage and the clear waters that made a submerged boat easy to track, elected to run on the surface for the Italian shore batteries at Assab. In the ensuring fight, Torricelli, firing her deck gun, almost hit Shoreham, which reported “two shells falling close ahead.” Then the three destroyers appeared and closed rapidly.

Kingston opened fire with her forward guns at 0536.

Torricelli, trailing a wide ribbon of oil, launched four torpedoes back at the

destroyer, but their wakes were clearly visible in the calm sea and Kingston

easily evaded. At first the British tried to clear the submarine’s decks, to

permit a boarding attempt. However, Kingston’s 40-mm shells struck one of her

own antennas and wounded eight crewmen. After that the destroyers shot to sink,

but they had to expend nearly seven hundred 4.7-inch rounds before a shell

finally wrecked Torricelli’s forward bow planes at 0605 and flooded the torpedo

room. The submarine sank at 0624.

After rescue operations Khartoum, with prisoners embarked,

set course for Perim while the other ships headed for Aden to refuel. At 1150 a

torpedo in Khartoum’s aft quintuple mount suddenly exploded, igniting a huge

fire in the after lobby. The crew could not control the conflagration, and

Khartoum ran for Perim Harbor, seven miles distant. There her men (and the

prisoners) abandoned ship, swimming for their lives. At 1245, no. 3 magazine

blew up, rendering the destroyer a total loss.

Red Sea Convoys

The first of the Red Sea convoys, collectively the BN/BS

series, consisting of nine ships including six tankers, gathered in the Gulf of

Aden on 2 July. Thereafter these convoys sailed up and down the Red Sea on a

regular schedule. Admiral Balsamo attempted to attack this traffic, but the

war’s opening months held little but frustration for his destroyers. On six

occasions in July, August, and September, they sortied at night in response to

aerial reports of Allied vessels but in every case failed to make contact.

Aircraft and the surviving submarines did little better. Guglielomotti

torpedoed the Greek tanker Atlas (4,008 GRT) from Convoy BN4 on 6 September

1940, while high-level bombing attacks damaged the steamship Bhima (5,280 GRT)

from BN5, which four Italian destroyers had failed to locate, on 20 September.

As Italian warships burned their oil reserves on

unsuccessful sorties, the Allied Red Sea Squadron grew stronger, deploying by

the end of August four light cruisers, three destroyers, and eight sloops.

Other warships passed through on their way to and from the Mediterranean. In

September, as traffic volume swelled, the Mediterranean Fleet lent the newly

arrived antiaircraft cruiser Coventry, which alternated with Carlisle along the

Aden–Suez route to provide extra protection against air attacks.

By October the Italian ships faced mechanical breakdowns,

the increasing exhaustion of crews by the extreme climate, and a growing

shortage of fuel. Nonetheless, they continued to sail. On the evening of 20

October, four destroyers weighed anchor to search for BN7, which aerial reconnaissance

had spotted sailing north. The plan called for the slower and more heavily

armed Pantera and Leone to distract the escort while Sauro and Nullo slipped in

to send a spread of torpedoes toward the merchant ships.

Australian sloop HMAS Yarra

Italian destroyer Pantera

Attack on Convoy BN7 and Battle of Harmil Island, 20–21

October 1940, 2320–0640

Conditions: Bright moon, calm sea

Allied ships—

BN7 Escort (Captain H. E. Horan): CL: Leander (NZ) (F); DD:

KimberleyD2; DS: Auckland (NZ), Indus (IN), Yarra (AU); MS: Derby, Huntley

BN7: thirty-two merchant ships and tankers

Italian ships—

Section I (Commander Moretti degli Adimari): DD: Sauro (F), Nullo Sunk

Section II (Commander Paolo Aloisi): DD: Pantera (F), Leone

The convoy timed its progress to pass Massawa around

midnight. The moon was bright, but haze reduced visibility toward the African

coast. At 2115 the Italian sections separated, and at 2321 Pantera detected

smoke off her starboard bow. She reported the contact to Sauro and began

maneuvering at twenty-two knots to position the low-hanging moon behind the

contact.

BN7 was thirty-five miles north-northwest of Jabal-al-Tair

Island (itself 110 miles east-northeast of Massawa) when Yarra, zigzagging in

company with Auckland, sighted Captain Aloisi’s ships ahead. Yarra challenged

and Pantera replied with a pair of torpedoes at 2331 and then another pair at

2334, at ranges fifty-five and sixty-five hundred yards, respectively. Shooting

over Yarra, she “lobbed a few shells” into the convoy. According to a wartime

British account, “a lifeboat in the commodore’s ship was damaged by splinters,

but otherwise no harm was done.” Leone, which trailed Pantera by 875 yards,

never fixed a target and thus did not fire torpedoes.

Yarra saw the torpedo flashes from broad on her port bow and

turned toward the enemy. Both sloops opened fire as torpedoes boiled past,

narrowly missing. The Italian ships altered away, shooting with their aft

mounts. Aloisi reported explosions and claimed two torpedo hits, but in fact,

his weapons missed. Kimberley was trailing the convoy. She rang up thirty knots

and steered northwest to close the action. Leander, sailing on the convoy’s

port beam, headed southwest, while the sloops and minesweepers stayed with the

merchantmen. Pantera and Leone, considering their mission successfully

accomplished, continued west-southwest and broke contact. They eventually

returned to Massawa via the south channel.

After the gunfire died away, Captain Horan steered Leander

northwest to cover Harmil Channel believing the enemy ships had retired in that

direction.

Upon receiving Pantera’s report, Sauro and Nullo had turned

to clear the area while the first group attacked and to put themselves in a

favorable position relative to the moon. This involved a ninety-degree port

turn at 0016 on 21 October and another at 0050. The section then headed

southeast, but for nearly an hour it encountered nothing. Finally, at 0148,

Leander and another ship hove into view. Sauro snapped off a single torpedo at

the cruiser (another misfired). In response Leander lofted star shell, and then

ten broadsides flashed from her main batteries in two minutes before she lost

sight of the target. Italian accounts say this engagement occurred at sixteen hundred

yards, while Leander’s report stated the enemy was more than eight thousand

yards away.

Sauro turned south by southwest and at 0207 attempted

another torpedo attack against the convoy. One weapon misfired, and although

Sauro claimed a hit with the other, it missed. At the same time Nullo detected

flashes that she believed came from an enemy torpedo launch, and within minutes

a lookout shouted that wakes were streaking toward the Italian destroyer’s bow.

At 0212 Sauro turned north and disengaged, eventually circling behind the

British and taking the south channel to Massawa. Nullo’s captain, however, put

his helm over even harder, “because it was [his] intention to attack, being

still in an opportune position to launch against the convoy, before taking

station in formation.” However, the rudder jammed for several minutes, causing

Nullo to circle and lose contact with Sauro.

At 0220 Leander’s spotlights fastened onto “a vessel painted

light grey proceeding from left to right”—in fact, Nullo steaming north. The

cruiser engaged from forty-six hundred yards off the Italian’s starboard bow.

Nullo returned fire, first against “destroyers” spotted astern (probably

Auckland) and then at Leander. The ships dueled for about ten minutes. The

Italian enjoyed one advantage: she employed flashless powder (the British noted

only two enemy salvos), whereas British muzzles flared brightly with each

discharge. Leander fired eight blind salvos (“little could be seen of their

effect”), but several rounds nonetheless hit home, damaging Nullo’s gyrocompass

and gunnery director. With this the Italian destroyer abandoned her attack

attempt and turned west-northwest running for Harmil Channel at thirty knots.

In the two actions Leander fired 129 6-inch rounds.

Guessing Nullo’s intention, the cruiser pursued in the

correct direction. At 0300 Kimberley joined, and at 0305 Leander turned back,

“appreciating that the enemy was drawing away from her at the rate of seven

knots and that the convoy might be attacked.” Kimberley continued, hoping to

intercept.

The British destroyer arrived off Harmil Island before dawn.

At 0540 her lookouts reported a shape to the south-southeast, and she closed to

investigate. Nullo’s lookouts likewise reported a contact. The sharp angle of

approach made it impossible to be certain, but the Italian captain assumed it

was Sauro, especially when it seemed to signal the Harmil Island station. He

was more “worried about the shallows scattered around the mouth of the

northeast passage and above all of the 3.7 meter sandbank immediately north of

his estimated 0500 position.”

At 0553 the British destroyer opened fire from 12,400 yards.

Surprised, Nullo took four minutes to reply and at 0605 swung sharply from a

northwest heading to a south-by-southwest course. By 0611 the range was down to

10,300 yards. Due to her prior damage, Nullo’s gunners fired over open sights,

while human chains passed shells up from the magazine. Harmil Island’s battery

of four 4.7-inch guns joined the action at 0615 from eighteen thousand yards.

At the same time, with the range now eighty-five hundred yards, Kimberley

turned south, emitting black funnel smoke, causing Nullo’s gunners to think

they had scored a hit.

At 0620 Nullo scraped a reef, opening her hull to flooding

and damaging a screw. Then, while the ship was setting course to round Harmil

Island, a shell exploded in the forward engine room and a second slammed into

the aft engine room. Nullo skewed sharply to the left and lost all power;

splinters swept the upper works. The captain ordered his men to prepare to

abandon ship while he angled the ship toward Harmil in an attempt to run it

aground. The aft mount continued in action until the heel became excessive.

Having expended 115 salvoes, Kimberley launched a torpedo to

dispatch her adversary; it missed, so she closed range and uncorked another.

The second torpedo slammed into Nullo at 0635 and blasted her in two.

Meanwhile, the Harmil battery finally found the range, and a shell struck

Kimberley’s engine room, wounding three men. Splinters cut the steam pipes; the

British destroyer lost power and came to a halt.

Kimberley’s men frantically patched the damage while the

drifting ship’s guns remained in action, shooting forty-five rounds of HE from

no. 3 mount, and achieving some hits that wounded four of the shore battery’s

crew. After a few long minutes, the destroyer restored partial power and pulled

away at fifteen knots. The shore battery fired its final shots at 0645, when

the range had opened to nineteen thousand yards. During the battle Kimberley

expended 596 SAP and 97 HE rounds.

After she was clear the destroyer lost steam pressure again.

Finally Leander arrived and towed Kimberley to Port Sudan. Nullo remained above

water; her guns ended up equipping a shore battery. On 21 October three

Blenheims reported destroying a wreck east of Harmil Island. This led the

British to conclude two enemy ships had been involved in the action.

The Aden command faulted the escort (except for Kimberley)

for demonstrating a lack of aggressiveness, although deserting the convoy to

chase unknown numbers of enemy destroyers through a murky night does not in

retrospect seem the best course of action either. The Italian ships, although

outnumbered, delivered two hit-and-run torpedo attacks, according to their

plan. However, while using widely separated divisions increased the probability

of finding the enemy, a natural consideration given the history of failed

interception attempts, it also guaranteed that the Italian forces would lack

the punch to take on the escort and deliver a meaningful attack. In fact, the

first Italian attack seemed more formulaic than a serious attempt to cause

damage.

The Italian East African squadron conducted another

(fruitless) sortie on 3 December 1940. It aborted a mission planned for early

January after British aircraft damaged Manin, one of the participants, and on

24 January it sortied again, without results. On the night of 2 February 1941,

however, three destroyers departed Massawa and deployed in a rake formation to

search for a large convoy known to be at sea.

Attack on Convoy BN14, 3 February 1941

Conditions: n/a

Allied ships—

Convoy Escort: CL: Caledon; DD: Kingston; DS: Indus (IN),

Shoreham

Convoy BN14: thirty-nine freighters

Italian ships—

DD: Pantera, Tigre, Sauro

Sauro spotted the enemy, made a sighting report, and

immediately maneuvered to attack. She launched three torpedoes at a group of

steamships and then, a minute later, at another dimly seen target marked by a

large cloud of smoke. She then turned away at speed. Her two sisters did not

receive the report, but ten minutes later Pantera stumbled across the enemy and

also fired torpedoes. The Italians heard explosions and later claimed

“probable” hits on two freighters. Tigre never made contact.

On her way to Massawa’s south channel, Sauro encountered

Kingston. Out of torpedoes, the Italian retreated at full speed. Concerned that

the British were attempting another ambush, the squadron concentrated on Sauro

and radioed for air support at dawn. In the event, the three destroyers safely

made port. The Italian East African press reported two freighters as probably

hit, but despite this claim, all torpedoes missed.

By April 1941 Imperial spearheads were probing Massawa’s

defensive perimeter. With Supermarina’s approval, Rear Admiral Mario Bonetti,

Balsamo’s replacement from December 1940, ordered a last grand gesture—an

attack by the three largest destroyers (Leone, Pantera, and Tigre) against Port

Suez, five hundred miles north, and a concurrent raid by the smaller destroyers

Battisti, Manin, and Sauro against Port Sudan. The British Middle Eastern

command had considered such an attack possible and had reinforced Port Suez

with two J-class destroyers and sent Eagle’s experienced air group south to

Port Sudan, while the carrier waited for mines to be swept from the Suez Canal

so she could proceed south.

The Italian venture ran into problems early when Leone

struck an uncharted rock forty-five miles out of Massawa. Flooding and fires in

her engine room forced her crew to abandon ship. Her two companions returned to

port, as the rescue operation left insufficient time for them to continue the

mission.

On the afternoon of 2 April the remaining Italian destroyers

sailed once again, this time against Port Sudan, 265 miles north. British

aircraft attacked them about two hours out of port but caused no damage. Then

Battisti suffered engine problems and scuttled herself on the Arabian coast.

The other four continued at top speed through the night and by dawn were thirty

miles short of their objective. However, Eagle’s Swordfish squadrons

intervened, sinking Sauro at 0715. The other ships headed for the opposite

shore, under attack as they went. Bombs crippled Manin at 0845. She eventually

capsized and sank about a hundred miles northeast of Port Sudan. Pantera and

Tigre made it to the Arabian coast and were scuttled there.

Caught off guard by the Italian sortie, British warships

rushed north. At 1700 Kingston found Pantera’s and Tigre’s wrecks. The two

ships had already been worked over by Wellesley bombers, but Kingston shelled

Pantera’s hulk and then torpedoed it, just to be sure.

The biggest Italian naval success in the Red Sea was a

Parthian shot that occurred on 8 April, with Massawa’s defenses breached and

ships scuttling themselves on all sides. MAS213, a World War I relic no longer

capable of even fifteen knots, ambushed the old light cruiser Capetown, which

was escorting minesweepers north of the port, and scored a torpedo hit from

just over three hundred yards. After spending a year in repair, the cruiser sat

out the rest of the war as an accommodation ship.

This was the Italian navy’s final blow in East Africa. The

capture of Massawa relieved Great Britain of the need to convoy the entire

length of the Red Sea and released valuable escorts for other duties. On 10

June an Indian battalion captured Assab, Italy’s last Red Sea outpost,

eliminating a pair of improvised torpedo boats. After that President Franklin

D. Roosevelt declared the narrow sea a nonwar zone, permitting the entry of

American shipping.

However, German aircraft continued to exert a distant influence

over the Red Sea, by mining the Suez Canal and attacking shipping that

accumulated to the south of the canal. As late at 18 September Admiral

Cunningham complained to Admiral Pound that “the Red Sea position is

unsatisfactory . . . about 5 of 6 ships attacked, one sunk [Steel Seafarer

(6,000 GRT)] and two damaged. . . . The imminent arrival at Suez of the monster

liners is giving me much anxiety. They are crammed with men and we can’t afford

to have them hit up.” In October 1941 the Suez Escort Force still tied up four

light cruisers, two fleet destroyers, two Hunt-class destroyers, and two

sloops. The British maintained a blockade off French Somaliland until December

1942.