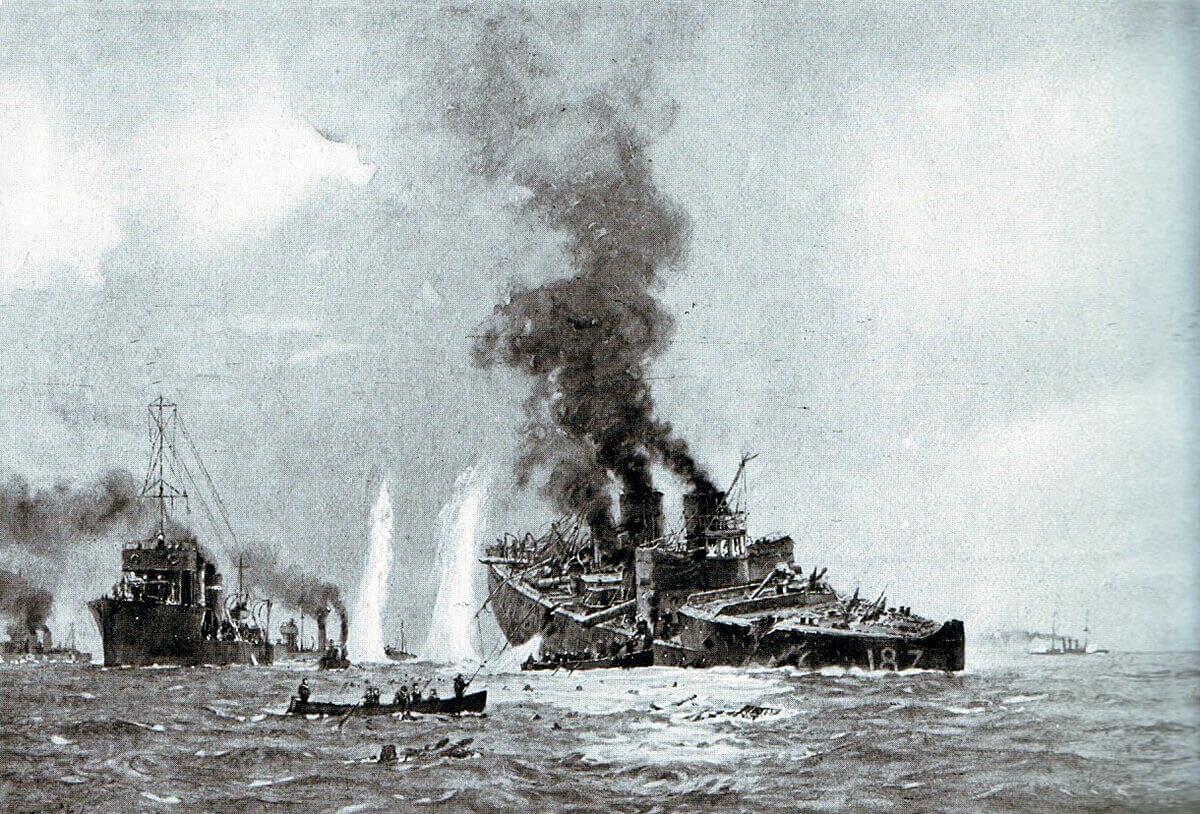

German destroyer V187 sinking during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War.

British light cruiser HMS Arethusa, Commodore Tyrwhitt’s flagship in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War.

During the first hour of 26 August 1914 the German cruiser

Magdeburg ran aground in fog 500 yards off the Odensholm lighthouse in the

Baltic. All efforts to refloat the vessel failed and her forecastle was blown

off to prevent her falling into enemy hands. Some of the crew were taken off by

an accompanying destroyer, but the captain and 56 of his men were taken

prisoner when two Russian cruisers arrived on the scene and opened fire,

causing the destroyer to beat a hasty retreat. To the Russians’ astonishment

and delight, the Magdeburg’s signal code book, cipher tables and a marked grid

chart of the North Sea were recovered from the body of a drowned signalman.

They were promptly passed to the British Admiralty which set up a radio

intercept intelligence branch known as Room 40. By mid-December the code

breakers were able to listen to the Imperial Navy’s radio traffic to their

hearts’ content.

As if this was not bad enough, on 28 August a strong raiding

force commanded by Commodore Roger Keyes penetrated the Heligoland Bight. The

raiders were not merely on Germany’s doorstep – they were halfway through her

front door. In the lead were two destroyer flotillas commanded by Commodore

R.Y. Tyrwhitt, followed by the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron under Commodore W.R.

Goodenough and Rear Admiral A.H. Christian’s 7th Cruiser Squadron. Standing off

and ready to intervene or administer the decisive coup de grace was Vice

Admiral Sir David Beatty’s 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron, consisting of the

battle cruisers Lion, Princess Royal, Queen Mary, New Zealand and Invincible

with their escorting destroyers. A flotilla of submarines was also attached to

the force with the task of alarming the enemy and confusing his response.

The subsequent engagement took place in a flat calm but was

a confused affair in which visibility was limited to two or three miles,

effectively denying the German coastal defence batteries on Heligoland Island

the chance to join in. The British destroyers fought a fast-moving action,

sinking one of their opposite numbers, V-187. However, at about 08:00,

Tyrwhitt’s flagship, the light cruiser Arethusa, was engaged with a German

cruiser, the Stettin. Unfortunately, the Arethusa had only been commissioned

two days previously, so her crew had neither the benefits of a shakedown cruise

nor gunnery practice – and, like the ship herself, her guns were also brand new

and still prone to jamming. A second enemy cruiser, the Frauenlob, joined in

the fight and Arethusa began to take a battering. Before long all her guns

except for the forecastle 6-inch were out of action for various reasons, an

ammunition fire had broken out and casualties were rising. Luckily, at this

point the light cruiser Fearless, the leader of the 1st Destroyer Flotilla,

arrived and drew off Stettin’s fire. At 08:25 one of Arethusa’s shells exploded

on Frauenlob’s forebridge, killing everyone in the bridge party, including her

captain. She sheered away out of the battle in the direction of Heligoland,

covered by Stettin. The first phase of the battle was over.

The High Seas Fleet command, believing that the only enemy

ships in the area were Arethusa, Fearless and the destroyers, now began

directing more of its own cruisers into the Bight. Fighting was renewed at

about 10:00, by which time Arethusa had recovered the use of all but two of her

guns although her maximum speed had been reduced to ten knots. Having seen

Frauenlob safely out of the action, Stettin returned to the fray, followed by

Stralsund, which immediately became involved in a duel with Arethusa. Four more

German cruisers, Koln, Kolberg, Strassburg and Ariadne, entered the fight

shortly after so that by 11:00 Tyrwhitt found himself in the midst of a

thoroughly disturbed hornet’s nest. He sent a radio signal to Beatty, still

some distance away to the north-west, requesting urgent assistance. Beatty

despatched Commodore Goodenough’s light cruiser squadron immediately and followed

with his battle cruisers at about 11:30.

For those British cruisers and destroyers already engaged

with the enemy, there was the constant fear that the German battle cruisers

would emerge from their anchorage in the Jade River and send them to the bottom

before help could arrive. They need not have worried, for in the present state

of the tide the enemy’s heavy warships drew too much water for them to be able

to cross the sandbar at the river’s mouth, a situation that would not change

until the afternoon. In the meantime, senior German commanders could only fume

with rage and frustration while the battle took its course.

Goodenough’s light cruisers arrived at about noon. When, at

12:15, the battle cruisers, led by Beatty in Lion, burst out of the northern

mist, there could no longer be any doubt as to the battle’s outcome.

Three of the enemy’s light cruisers, Mainz, Koln and

Ariadne, were sunk after fighting to the bitter end, and the rest escaped in a

damaged condition. In addition, the battle cost Germany 1,200 officers and men

killed or captured. Among those killed aboard the Koln was Rear Admiral

Leberecht Maas, commander of the German light forces in the Bight. The British

destroyer Lurcher rescued many survivors from the Mainz, including Lieutenant

von Tirpitz, son of the German Minister of Marine. Winston Churchill, then

First Lord of the Admiralty, chivalrously arranged for the International Red

Cross to advise the Admiral that the young officer had survived the battle.

British casualties amounted to 35 killed and some 40 wounded. Most of the

damage sustained was repaired in a week.

The outcome of the battle created a tremendous sense of

shock throughout Germany. The Kaiser sent for his Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral

Hugo von Pohl. He was horrified by the loss that had been incurred during a

comparatively minor engagement and impressed upon Pohl that the fleet should

refrain from fighting ‘actions that can lead to greater losses.’ Pohl promptly

telegraphed Ingenohl to the effect that ‘In his anxiety to preserve the fleet

His Majesty requires you to wire for his consent before entering a decisive

action.’ In other words, before involving the High Seas Fleet in any sort of

large scale action, Ingenohl, a professional naval officer of many years standing,

should seek the advice of that old sea dog, Wilhelm Hohenzollern.

The battle and its aftermath marked the beginning of the end

of Tirpitz’s career. The admiral had produced a fleet of fine ships that were

in some respects better than those of the Royal Navy. They were, for example,

compartmentalised to a greater extent, enabling them to withstand considerable

punishment, and they were equipped with fine optical gun-sights.

Understandably, he did not wish to see his creation destroyed in a fleet

action, but neither did he want to see it tied up at its moorings for the

duration of the war. In his memoirs, written in 1919, he expressed outrage at

Wilhelm’s diktat:

Order issued by the Emperor following an audience with Pohl – to which I was not summoned – restricted the initiative of the Commander-in-Chief North Sea Fleet. The loss of ships was to be avoided, while fleet sallies and any greater undertakings must be approved by His Majesty in advance. I took the first opportunity to explain to the Emperor the fundamental error of such a muzzling policy.

This argument met with no success; on the contrary, there sprang up from that day forth an estrangement between the Emperor and myself which steadily increased.

Today, Pohl’s name means nothing to most people, even in

Germany, yet there were two remarkable things about him. First, in 1913 he had

been honoured in Great Britain by an appointment as a Companion of the Order of

the Bath, a surprising adornment for one of the most senior officers in a rival

navy. Secondly, he was quick to realise that the Imperial Navy’s U-boat arm was

capable of inflicting far greater damage on the enemy than the surface fleet.

Although the German light cruiser Hela was torpedoed and sunk by the British

submarine E-9 (commanded by the then Lieutenant Max Horton, who became Commander-in-Chief

Western Approaches during World War Two) the months of September and October

1914 belonged to the U-boats, which fully justified Pohl’s opinion of their

potential. On 5 September the light cruiser Pathfinder was torpedoed off the

Scottish coast and sank with heavy loss of life. On 22 September Lieutenant

Otto Weddigen’s U-9 sank, in turn, the elderly cruiser Aboukir, then her sister

ship Hogue as she was picking up survivors, then a third sister, Cressey, which

opened an ineffective fire against the submarine’s periscope. Of the 1,459

officers and men manning the three cruisers, many of them elderly reservists,

only 779 were rescued by nearby trawlers. Weddigen’s remarkable feat earned him

Imperial Germany’s most coveted award, the Pour le Merite. On 15 October U-9

claimed a further victim in the North Sea, the ancient protected cruiser Hawke

which, having been launched in 1893, had really reached the end of her useful

life. The same month saw the seaplane carrier Hermes torpedoed and sunk by U-27.

In addition, U-boats had sunk a modest tonnage of Allied merchant shipping,

although this would rise to horrific levels as the war progressed. To end a

very depressing month, the dreadnought battleship Audacious struck a mine laid

by the armed merchant cruiser Berlin off the north coast of Ireland and sank as

the result of an internal explosion.