Despite his eventual recovery, the sickness that struck

Cesare Borgia on that fateful August 12 was to destroy his life. The disappearance

of Alexander from the scene created a vacuum which brought chaos in its train;

several cities rose in open revolt. A French army under Francesco Gonzaga had

already reached Viterbo, only forty miles from Rome; meanwhile, a Spanish army

under its brilliant young general Gonsalvo de Córdoba was hurrying northward

from Naples. In normal times Cesare might have been able to deal with the

situation; but now, desperately ill in the Vatican, he was powerless to take

the swift military action necessary to save his career. Political action was

his only hope; and that meant ensuring from his father’s successor the support

he needed. He managed to secure some 100,000 ducats from his family’s private

treasury, and with this, from his sickbed, he hoped to bribe the coming

conclave. At all costs he must prevent the election of his most dangerous

enemy, Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, who had been

living in exile in France during the greater part of Alexander’s pontificate.

The surest way of achieving this was, he knew, to block the cardinal’s return

to Rome.

He failed. Della Rovere arrived unscathed, together with

Cardinal Georges d’Amboise, Louis XII’s chief counselor, who was as ambitious

for the tiara as he was. A third determined candidate was Cardinal Ascanio

Sforza, who had broken with Alexander over his pro-French policies; now

released from prison by d’Amboise in order to cast his vote for the Frenchman,

he found himself unexpectedly popular and began lobbying on his own account. In

fact, d’Amboise was soon effectively eliminated: a French pope at such a moment

seemed almost as bad an idea as another Spanish one, particularly after della

Rovere had spread the word that it would mean the second removal of the Papacy

to France. The struggle seemed to be between della Rovere and Sforza; neither,

however, could accumulate the votes necessary to carry the day, and the choice

of the cardinals finally fell on a compromise candidate, Francesco

Todeschini-Piccolomini, Archbishop of Siena, who took the name of Pius III as a

tribute to his uncle Pius II. He was already sixty-four but looked and acted a

good deal older and was crippled by gout. There was a general feeling that he

would not last long.

In fact, he lasted twenty-six days, one of the shortest

pontificates in history. He had been a fine, upstanding churchman of

unquestioned integrity and had been the only cardinal brave enough to protest

when Alexander had transferred papal territories to his son the Duke of Gandia.

There were strong indications that, had he lived, he would have summoned a

General Council and driven through the reforms that were so desperately needed.

With his death on October 18, 1503, the opportunity was lost—and it was the

Church that paid the price.

One of the shortest pontificates was followed by the

shortest conclave. It lasted for a few hours on November 1. Giuliano della

Rovere had done his work well and had spread his money astutely; he had even

managed to secure the vote of Ascanio Sforza, the only other serious potential

contender. And it was plain to all that he was born to command. In the words of

the Venetian envoy:

No one has any influence over him, and he consults few or

none. It is almost impossible to describe how strong and violent and difficult

he is to manage. In body and soul, he has the nature of a giant. Everything

about him is on a magnified scale, both his undertakings and his passions. He

inspires fear rather than hatred, for there is nothing in him that is small or

meanly selfish.

It might have been thought that the election of this

terrifying figure as Pope Julius II—he had scarcely bothered to change his

name—would spell the end for Cesare Borgia. It did not. Just two weeks before,

the Orsini had stormed Cesare’s palace in the Borgo, and he, by now fully

restored to health, had taken refuge in the Castel Sant’Angelo. He was still

there when messengers arrived from della Rovere assuring him of his protection

in the event of their master’s being elected. Accordingly, the moment he heard

of the election, Cesare had returned to his old quarters in the Vatican. But,

as he well knew, he was there only on sufferance. It was in Julius’s interest

to string him along, simply because his power base was the Romagna, where

Venice was helping herself to more and more cities; Julius for the moment had

no army and consequently needed Cesare’s. When he had no more use for the Duke

of Valentinois, he would unquestionably ditch him.

As of course he did. Cesare Borgia still retained much of

his old fire, but without his father’s protection and support the days of power

and glory were gone and he fades out of our story. Exiled to Spain in 1504, he

died in 1507, fighting for his brother-in-law King John of Navarre at the siege

of Viana. He was thirty-one years old.

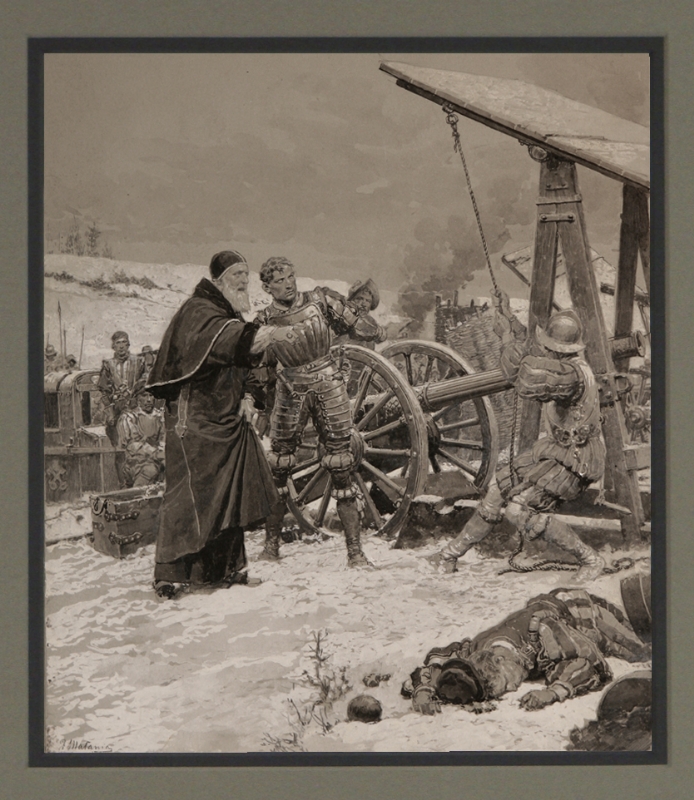

There is a story that when Michelangelo was working on his

fourteen-foot bronze statue of Pope Julius II and suggested putting a book in

the pope’s left hand, Julius replied, “Nay, give me a sword, for I am no

scholar!” He spoke no more than the truth; he was indeed a soldier, through and

through. Not since Leo IX—at Civitate in 1053—had a pope led his army

personally in battle; Julius did so on several occasions, notably when, in

January 1511, aged sixty-eight and wearing full armor, he personally trudged

with his army through deep snowdrifts to capture Mirandola from the French. His

world, like that of his enemy Alexander VI, was exclusively temporal; for the

spiritual he had no time or inclination, and to establish the Papacy firmly as

a temporal power was the primary task to which he devoted his pontificate. This

involved, inevitably, a good deal of fighting. Already by the autumn of 1504 he

had succeeded in bringing both France and the empire into an alliance against

Venice—another instance of foreign armies being invited into Italy to settle

what were essentially domestic differences—and in April 1506, immediately after

laying the cornerstone of the new St. Peter’s, he led his entire Curia on an

expedition to regain Perugia and Bologna from the local families who saw

themselves as independent despots and ruled accordingly. The Baglioni in

Perugia surrendered—one suspects rather to the pope’s disappointment—without a

fight; the Bentivoglio in Bologna put up rather more resistance, but eventually

the paterfamilias, Giovanni—who had ruled there for over forty years—fled to

France and the pope made his triumphal entry into the city.

Venice, however, remained his archenemy. Five years before,

he had been her most trusted friend in the whole of the Sacred College; but she

had recently seized several cities in the Romagna that had previously fallen to

Cesare Borgia. Those cities, which had traditionally belonged to the Holy See,

she had refused to surrender; so now Julius was determined on her destruction.

Italy, as he saw it, was divided into three. In the North was French Milan, in

the South Spanish Naples. Between the two there was room for one—but only

one—powerful and prosperous state; and that state, Julius was determined, must

be the Papacy. A new stream of emissaries was dispatched from Rome—to France

and Spain, to the Emperor Maximilian, to Milan, Hungary, and the Netherlands.

All bore the same proposal, for a joint expedition by Western Christendom

against the Venetian Republic and the consequent dismemberment of its empire.

The states of Europe could not be expected to feel much

sympathy for such a policy. Their motive for joining the proposed league was

neither to support the Papacy nor to destroy Venice but to help themselves.

However much they might try to present their action as a blow struck for

righteousness against iniquity, they knew perfectly well that their own conduct

was more blameworthy than ever Venice’s had been. But the temptation was too

great, and the territories promised them were irresistible. They accepted. So

it was that what appeared to be the death warrant of the Venetian Empire was

signed at Cambrai on December 10, 1508, by Margaret of Austria on behalf of her

father, Maximilian, and by Cardinal d’Amboise for the King of France. Julius

himself, though his legate was present at Cambrai, did not formally join the

League until the following spring; he seems to have been uncertain whether the

other signatories were in earnest. But when in March 1509 King Ferdinand II of

Aragon announced his formal adherence, he hesitated no longer. On April 5 he

openly associated himself with the rest and placed Venice under an interdict,

and on the fifteenth the first French soldiers marched into Venetian territory.

A month later, on May 14, the French met the Venetians just outside the village

of Agnadello. For Venice, it was catastrophe. Her casualties were about 4,000,

and her entire mainland empire was as good as lost. Before the end of the month

the pope’s official legate received back the fateful lands in the Romagna with

which the whole tragedy had begun.

But very soon the pendulum began to swing. Less than two

months after Agnadello came the first reports of spontaneous uprisings on the

mainland in favor of Venice, and on July 17, after just forty-two days as an

imperial city, Padua returned beneath the sheltering wing of the Lion of St.

Mark. There had as yet been no sign of Maximilian in Italy, but the news of

Padua’s defection brought him down from Trento with an army. His siege began on

September 15, and for a fortnight the German and French heavy artillery pounded

away at the walls, reducing them to rubble; yet somehow every assault was

beaten back. On the thirtieth the emperor gave up.

When Pope Julius was told of the reconquest of Padua, he

flew into a towering rage, and when, after Maximilian’s failure to recover it,

he heard that Verona too was likely to declare for Venice, he is said to have

hurled his cap to the ground and blasphemed St. Peter. His hatred of Venice was

as vindictive as ever, and although he had agreed to accept a six-man Venetian

embassy in Rome, it was soon clear that he had done so only in order to inflict

still more humilation on the republic. On their arrival in early July, the

envoys had been forbidden, as excommunicates, to enter the city until after

dark, to lodge in the same house, and even to go out together on official

business. One only was granted an audience, which rapidly deteriorated into a

furious diatribe by Julius himself. Not, he maintained, until the provisions of

the League of Cambrai had been carried out to the letter and the Venetians had

knelt before him with halters around their necks would he consider giving them

absolution.

At first Venice rejected the pope’s terms outright; she even

appealed to the Turkish sultan for support, requesting as many troops as he

could spare and a loan of not less than 100,000 ducats. But the sultan remained

silent, and by the end of the year the Venetians saw that they must capitulate.

And so, on February 24, 1510, Pope Julius II took his seat on a specially

constructed throne outside the central doors of St. Peter’s, twelve of his

cardinals around him. The five Venetian envoys, dressed in scarlet—the sixth

had died a few days before—advanced toward him and kissed his foot, then knelt

on the steps while their spokesman made a formal request on behalf of the

republic for absolution and the Bishop of Ancona read out the full text of the

agreement. This must have made painful listening for the envoys—not least

because it lasted for a full hour, during which time they were forced to remain

on their knees. Rising with difficulty, they received twelve scourging rods

from the twelve cardinals—the actual scourging was mercifully omitted—swore to

observe the terms of the agreement, kissed the pope’s feet again, and were at

last granted absolution. Only then were the doors of the basilica opened, and

the assembled company proceeded in state for prayers at the high altar before

going on to Mass in the Sistine Chapel—all except the pope, who, as one of the

Venetians explained in his report, “never attended these long services.”

The pendulum, it seemed, was swinging again. The news of the

pope’s reconciliation with Venice had not been well received by his fellow

members of the League; at the absolution ceremony the French, imperial, and

Spanish ambassadors to the Holy See, all of whom were in Rome at the time, were

conspicuous by their absence. Although Julius made no effort to dissociate

himself formally from the alliance, he was soon afterward heard to boast that

by granting Venice absolution he had plunged a dagger into the heart of the

King of France—proof enough that he now saw the French, rather than the

Venetians, as the principal obstacle to his Italian policy and that he had

effectively changed sides. By the high summer of 1510 his volte-face was

complete, his new dispositions made. His scores with Venice had been settled;

now it was the turn of France.

By all objective standards, Pope Julius’s action was

contemptible. Having encouraged the French to take up arms against Venice, he

now refused to allow them the rewards which he himself had promised, turning

against them with all the violence and venom that he had previously displayed

toward the Venetians. He also opened new negotiations with the emperor in an

attempt to turn him, too, against his former ally. His claim, regularly

resurrected in his defense by later apologists, that his ultimate objective was

to free Italy from foreign invaders, would have been more convincing if he had

not invited those particular invaders in in the first place.

There was, in any case, another motive for the pope’s sudden

change of policy. Having for the first time properly consolidated the Papal

States, he was now bent on increasing them by the annexation of the Duchy of

Ferrara. Duke Alfonso II, during the past year, had become little more than an

agent of the French king; his saltworks at Comaccio were in direct competition

with the papal ones at Cervia; finally, as husband of Lucrezia Borgia, he was

the son-in-law of Alexander VI—a fact which, in the pope’s eyes, was alone more

than enough to condemn him. In a bull circulated throughout Christendom,

couched in language that St. Peter Martyr said made his hair stand on end, the

luckless duke was anathematized and excommunicated.

In the early autumn of 1510 Pope Julius had high hopes for

the future. A joint papal and Venetian force had effortlessly taken Modena in

mid-August, and although Ferrara was strongly fortified there was good reason

to believe that it would not be able to withstand a well-conducted siege. The

pope, determined to be in at the kill, traveled north by easy stages and

reached Bologna in late September. The Bolognesi gave him a frosty welcome.

Since the expulsion of the Bentivoglio in 1506 they had been shamefully

misgoverned and exploited by papal representatives and were on the verge of

open revolt. The governor, Cardinal Francesco Alidosi, had already once been

summoned to Rome to answer charges of peculation and had been acquitted only

after the intervention of the pope himself, whose continued fondness for a man

so patently corrupt could be explained, it was darkly whispered in Rome, only

in homosexual terms. But the tension inside the city was soon overshadowed by a

yet graver anxiety. Early in October a French army under the Seigneur de Chaumont

and Viceroy of Milan marched south from Lombardy and advanced at full speed on

Bologna. By the eighteenth it was three miles from the gates.

Pope Julius, confined to bed with a high fever in a fundamentally

hostile city and knowing that he had less than a thousand of his own men on

whom he could rely, gave himself up for lost. “O, che ruina è la nostra!” he is

reported to have groaned. His promises to the Bolognesi that they would be

exempted from taxation in return for firm support were received without

enthusiasm, and he had already opened peace negotiations with the French when,

at the eleventh hour, reinforcements arrived from two quarters simultaneously—a

Venetian force of light cavalry and a contingent from Naples, sent by King

Ferdinand as a tribute after his recent papal recognition. The pope’s courage

flooded back at once. There was no more talk of a negotiated peace. Chaumont,

who seems to have felt some last-minute qualms about laying hands on the papal

person, was persuaded to withdraw, a decision which did not prevent Julius from

hurling excommunications after him as he rode away.

It is hard not to feel a little sorry for the Seigneur de

Chaumont. He was dogged by ill luck. Again and again we find him on the point

of a major victory, only to have it plucked from his grasp. Often, too, there

is about him more than a touch of the ridiculous. When Julius was besieging

Mirandola, Chaumont’s relief expedition was twice delayed: the first time when

he was hit on the nose by an accurately aimed snowball which happened to have a

stone lodged in it, and then again on the following day when he fell off his

horse into a river and was nearly drowned by the weight of his armor. He was

three days recovering, only sixteen miles from the beleaguered castle; as a

result, Mirandola fell. A month later, his attempt to regain Modena failed

hopelessly, and on February 11, 1511, aged thirty-eight, he died of a sudden

sickness which he—though no one else—ascribed to poison, just seven hours

before the arrival of a papal letter lifting his sentence of excommunication.

But by this time the Duke of Ferrara, on whom the ban of the

Church weighed rather less heavily, had scored a brilliant victory over a papal

army which was advancing toward his city along the lower reaches of the Po, and

Julius was once again on the defensive. In mid-May Chaumont’s successor, Gian

Giacomo Trivulzio, led a second march on Bologna, and on his approach the

inhabitants, seeing their chance of ridding themselves once and for all of the

detested Cardinal Alidosi, rose in rebellion. The cardinal panicked and fled

for his life without even troubling to warn either the Duke of Urbino, who was

encamped with the papal troops in the western approaches, or the Venetians, a

mile or two away to the south; and on May 23 Trivulzio entered Bologna at the

head of his army and restored the Bentivoglio to their old authority.

Cardinal Alidosi, who in default of other virtues seems at

least to have possessed a decent sense of shame, barricaded himself in his hometown,

Castel del Rio, to escape the papal wrath, but he need not have bothered.

Julius, who had prudently retired a few days earlier to Ravenna, bore him no

grudge. Even now, in his eyes, his beloved friend could do no wrong: he

unhesitatingly laid the entire blame for the disaster on the Duke of Urbino,

whom he summoned at once to his presence. The interview that followed is

unlikely to have diminished the duke’s long-standing contempt for Alidosi, for

whose cowardice he was now being made the scapegoat. When, therefore, on

emerging into the street he found himself face to face with his old enemy, who

had just reached Ravenna to give the pope his own version of recent events, his

pent-up anger became too much for him. Dragging the cardinal from his mule, he

attacked him with his sword; Alidosi’s retinue, believing that he might be

acting under papal orders, hesitated to intervene and moved forward only when

the duke remounted his horse and rode off to Urbino, leaving their master dead

in the dust.

The grief of Pope Julius at the murder of his favorite was,

we read, terrible to behold. Weeping uncontrollably and waving aside all

sustenance, he refused to stay any longer in Ravenna and had himself carried

off at once to Rimini in a closed litter, through whose drawn curtains his sobs

could be plainly heard. But there were more blows in store. Mirandola, for

whose capture he had always felt himself personally responsible, was within a

week or two to be lost to Trivulzio. The papal army, confused, demoralized, and

now without a general, had disintegrated. With the recapture of Bologna, the

way was open to the French to seize all the Church lands in the Romagna for

which he had fought so hard and so long. All the work of the last eight years

had gone for nothing. And now, at Rimini, the pope found a proclamation nailed

to the door of the cathedral, signed by no fewer than nine of his own cardinals

with the support of Maximilian and Louis of France, announcing that a General

Council of the Church would be held at Pisa on September 1 to investigate and

reform the abuses of his pontificate.