Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was born in 1838. He served in

the Royal Wurttemberg Army, in which he fought during the Franco-German War of

1870. In 1890 he left the Army feeling, as did many South German noblemen, that

Prussia had far too much influence in the recently created German Empire. He

then devoted himself to the development of the rigid dirigible airship which

has born his name ever since. In fact, his organisation, the Luftshiffbau

Zeppelin was not alone in manufacturing this type of airship, the Luftshiffbau

Schutte-Lanz being a competitor during the early years, although by custom ever

since every rigid airship has become known as a Zeppelin, just as vacuum

cleaners are known as Hoovers and raincoats as Macintoshes.

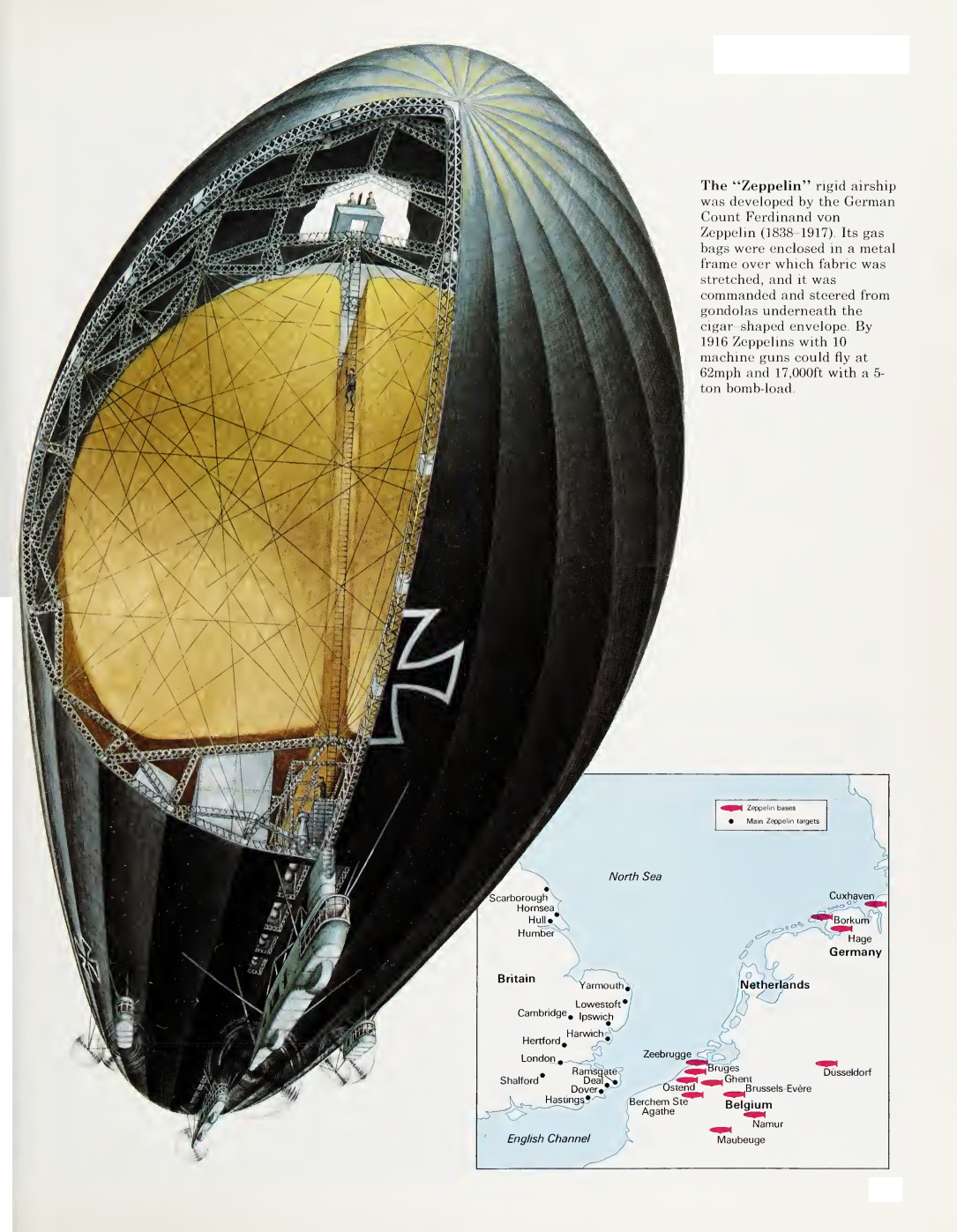

Zeppelin chose hydrogen as the lifting agent for his

airships, despite the terrible danger of fire, the outbreak of which was almost

always fatal to the ships. The hydrogen was contained within huge gasbags along

the interior of the hull, with provision for venting and water ballast tanks

used to maintain stability while ascending or descending. These were contained

in a long, sausage-shaped hull based on a complex internal girder construction

surrounded by a flexible skin. Control and communications gondolas were

suspended below, as were the ship’s engines, the number of which varied

according to type.

At first, Zeppelin’s organisation was not a financial

success and it was not until 1911 that his airline, the Deutsche

Luftschiffahrts AG began to show that large numbers of passengers could be

carried at a profit. This aroused the interest of the Imperial German Army and

Navy. The obvious advantages were that the Zeppelin had a very long in-flight

endurance which made it capable of longrange reconnaissance and, of course, it

could also be armed with bombs for dropping on specific targets. Of the

disadvantages, fire has already been mentioned. In addition, the girder

construction was so flimsy that clumsy handling in a shed or high winds on

take-off or landing could wreck a ship. Even more serious was the fact that

Zeppelins were extremely difficult to navigate. Even modest winds were capable

of pushing the huge, lighter-than-air hulls many miles off course, while cloud

cover could make it impossible to obtain a fix on the ground below. Later, a

small car containing one or two observers and a telephone could be lowered by

electric winch through the cloud and provide a view of the ground below, but

the idea was not a success.

During World War One, Zeppelins served in every German

theatre of war save East Africa, and even there one tried to get through,

albeit unsuccessfully, by overflying Egypt and the Sudan. The Army preferred to

use them for deep reconnaissance but would occasionally mount a bombing mission.

The Navy used them as scouts for the operations of the High Seas Fleet but also

carried out raids well inland into England, proving that nowhere was safe from

the attentions of the Imperial Navy. Naval Zeppelin bases were established near

Cuxhaven, at Ahlhorn near Oldenburg, Wittmundshaven (East Friesland), Tondern

(Schlewig-Holstein, now Denmark) and, for a while, Hage, south of Nordeny. From

these their route took them on a south-westerly course from which they would

cross the North Sea to the East Anglian coast, from which the glow of London’s

lights provided a distant beacon to steer by. Having carried out their mission,

they would leave England by crossing the Kent coast and then head north-east to

home.

Huge though the Zeppelins were, they generated very little

awe in the professional flying community. In 1914 Royal Naval Air Service and

Royal Flying Corps squadrons had been posted to the French and Belgian coast as

a defence against German air operations in the Channel. On 8 October, flying a

Sopwith Tabloid, Lieutenant R.G.L. Marix located a Zeppelin shed at Dusseldorf

and dropped four 20-lb bombs onto it from a height of 600 feet. The resulting

explosions were quickly followed by a roaring inferno, the flames of which

reached as high as 500 feet, signifying the end of an Army Zeppelin, Z-9.

Although the Tabloid received some damage from enemy fire, Marix managed to

nurse it back to within 20 miles of Antwerp, completing the journey home on a

borrowed bicycle. The following day the Allies withdrew from the city.

On 21 November an even more ambitious RNAS raid with three

Avro 504bs was mounted from Belfort in Alsace against the birthplace of the

Zeppelin, Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance. One airship was wrecked and

considerable damage was done to the hangars and other facilities of this

airship holy-of-holies. One aircraft was shot down, its pilot being seriously

injured when he was attacked by a civilian mob. In contrast, the German

military treated him with respect and great kindness while he was recovering in

hospital.

On Christmas Day 1914 further incidents demonstrated how the

naval air war was likely to develop. A squadron of light cruisers under the

command of Commodore R.Y. Tyrwhitt escorted three specially converted Channel

ferries, Engadine, Riviera and Empress, across the North Sea to a position

close to the mouth of the Elbe, from which an attack could be made on the

Zeppelin sheds at Cuxhaven. Nine Short floatplanes were lowered into the sea,

of which only seven managed to lift off. The remainder flew to Cuxhaven where,

although they were unable to identify the sheds, their appearance caused

uproar. As the High Seas Fleet relied on Zeppelins for much of its reconnaissance,

the risk of future raids was only too real. Furthermore, the German high

command was seriously unsettled by the fact that so much valuable information

on the fleet’s disposition had been gathered by the British pilots that a

number of warships were moved immediately. Amid the hullabaloo, the battle

cruiser Von der Tann was involved in a collision and so seriously damaged that

she had to be docked. Three of the floatplanes returned safely to their

carriers. The pilots of three more were picked up by the submarine E11, and the

last became a passenger aboard a Dutch fishing boat.

Meanwhile, a counter-attack had been launched on Tyrwhitt’s

cruisers by two Zeppelins, L5 and L6, plus a number of seaplanes. None were

hit, although some were near-missed and finally the German aircraft droned off.

L6, with her crew frantically slapping patches on 600 bullet holes hissing

hydrogen out of her gasbags, was very lucky to get home.

It is, of course, impossible to describe all the raids that

took place over four years in a single chapter. Naturally, the Kaiser insisted

in regulating what was going on and insisted that London was not to be attacked

west of the Tower. This ruled out most of the best targets, including the City.

The Imperial Chancellor, Theobald Bethmann-Holweg gave permission for the City

to be attacked at weekends, when it was empty. It was then pointed out that it

emptied every night, so that restriction was removed.

Finally, the Kaiser permitted attacks throughout the

capital, with the exception of historic buildings and royal palaces. Nature

imposed her own limitations when Zeppelin operations were restricted to the

moonless half of the month. The first attack on the United Kingdom took place

on 19/20 January 1915 and caused very little damage. In all, 42 raids were

launched during the year with a variable number of airships, the first

strategic air offensive aimed at the United Kingdom, with very mixed results,

including the needless destruction of a large number of glasshouses at

Cheshunt.

London was not attacked until 31 May, when seven people were

killed and 38 wounded. On 6 June L13, commanded by Lieutenant Commander

Heinrich Mathy, a brilliant navigator and the nearest thing to a Zeppelin ace,

attacked Hull, causing £45,000 of damage. A riot ensued in which property

believed to be in German ownership was wrecked. It was not just that fear was

getting the better of people; they were angry, too, that the powers that be

were apparently failing to provide them with adequate protection and several Royal

Flying Corps personnel were roughed-up because of it. This was not justified,

because the threat was being taken very seriously and a great deal was already

being done, although it would be some time before a fully integrated defence

system became operational.

On 8 September, Mathy was back in L13, carrying a two-ton

bomb-load, including one of the new 660-lb bombs specially designed for use

against England. This time his target was the City, in which he started

extensive fires and destroyed buildings in the area north of St Paul’s

Cathedral. Anti-aircraft fire forced him to climb hurriedly to 11,200 feet, but

his last bombs was used to damage the railway track leaving Broad Street

Station and to destroy two motor buses. On this occasion he had caused over

£500,000 worth of damage, killed 22 people and injured 87 more. Such was public

anger that on 12 September the Admiralty appointed Admiral Sir Percy Scott, a

gunnery expert of note, to command London’s anti-aircraft defences.

One of the most remarkable raids of all took place on the

night of 13/14 October, involving L15 under the command of Lieutenant Commander

Jaochim Breihaupt, another excellent navigator. Breihaupt penetrated central

London and, flying steadily from west to east to the north of The Strand,

dropped his bombs on Exeter Street, Wellington Street, Catherine Street, Aldwych,

the Royal Courts of Justice, Carey Street, Lincoln’s Inn, Hatton Garden and

Farringdon Road before heading for home. Behind lay a trail of death and

destruction, including 28 killed and 60 injured. The number of casualties could

have been higher as Breihaupt’s course took him close by the capital’s theatre

land, where places of entertainment were packed to the doors. While leaving the

target area, Breihaupt was also forced to climb sharply to avoid anti-aircraft

fire, and noted with alarm that several aircraft were searching for him at a

lower level, proof that the defence was stiffening.

Breihaupt’s attack may have unsettled some Londoners, but in

certain circles it was simply not done to acknowledge the fact. At the height

of the attack, about 22:30, Mrs Patrick Campbell, the doyenne of the London

stage and leading member of British society, was being fitted with a dress. She

was leaning out of her window, trying to discover the cause of all the fuss,

with two seamstresses hanging onto her bottom for dear life. ‘They’re bombing

Derry and Thoms!’ she announced in total disbelief. Obviously, the attempted

destruction of one’s favourite fashion house was taking things beyond

acceptable limits.

During this period, unless luck was on their side, aircraft were

at a disadvantage when engaging Zeppelins, for not only were they unable to

match the airships’ ability to gain altitude rapidly, their machine gun

ammunition was unable to do more than puncture the gasbags inside the hull,

damage which could be repaired quickly by a trained crew. An alternative was to

drop bombs on the airship from above, but that was a very hit and miss affair,

even if the necessary height could be gained. However, on the night on 6/7 June

1915 Sub-Lieutenant R.A.J. Warneford, piloting a tiny Morane, was on his way to

bomb the Zeppelin sheds at Berchem Ste Agathe when he spotted LZ-37 over

Ostend. He closed in to attack but was not only driven off by machine gun fire,

but also chased by the monster for a while. Without losing sight of the

airship, he put his machine into a slow, steady climb until he reached the

height of 11,000 feet. Turning off his engine, he glided noiselessly down on

LZ-37, 4,000 feet below, and, flying along the back of his opponent, dropped

six 20-lb bombs onto it. Some must have detonated on the airship’s hard

internal skeleton, for there was a huge explosion that blew the little Morane

upside down and caused some internal damage to the engine. Having recovered

control of his machine, Warneford could see the flaming mass hurtling

earthwards. It smashed into a convent, the only survivor being a quartermaster

named Alfred Muhler who was thrown out of the control gondola when it crashed through

a roof, landing on a bed bruised and singed but alive. For his part, Warneford

managed to land his aircraft in enemy territory, where he was able to repair

the damage and return home. His exploit won him the Victoria Cross but his

story had a sad ending for, ten days later, he was killed in a flying accident.

In 1916 the number of Zeppelin raids mounted against ‘the

island,’ as the crews termed the United Kingdom, increased three-fold, although

the results achieved were far from commensurate with the additional effort

involved. The principal reason for this was that the anti-aircraft defences of

London and the Home Counties had improved beyond recognition. New and improved

anti-aircraft guns were deployed throughout the capital and suburbs and in a

secondary ring in the outlying hinterland, leaving a corridor in which British

fighter aircraft could operate against the raiders without the risk of being

hit by the anti-aircraft batteries. These were supplemented by searchlights and

barrage balloons between which cable aprons were stretched, forcing the

attackers to climb and therefore lose accuracy. These defences were duplicated

to a lesser degree around the Thames estuary, the Kent and Essex coasts and

further north along the east coast. In addition, the Royal Navy stationed guard

ships along the Zeppelins’ most likely avenues of approach, armed with

anti-aircraft weapons. Special machine gun ammunition was also added to the

fighters’ armament, including Brock incendiary rounds, developed by the

firework company of the same name, and Pomeroy explosive rounds. These were

mixed together in the drum magazines of the Lewis guns that armed the

antiairship fighters.

In August 1916 Admiral Reinhard Scheer received a letter

from Captain Peter Strasser, the energetic operational commander of the

Imperial Navy’s airship arm, promising him that his Zeppelins would inflict

such serious damage on British civilian morale and economic life that their

recovery was unlikely. It was indeed true that much larger, improved airships

with the capacity to climb higher were being introduced, and that raids were

now being carried out by groups of Zeppelins rather than by individual ships.

However, the old problem of faulty navigation persisted, with commanders

returning home convinced that their bombs had hit their target when they had

actually landed many miles away. Again, the standard airship engine was a

veritable minefield of trouble, causing numerous sorties to be aborted and

contributing to the loss of ships. In the circumstances, it was an unwise

prediction, especially as the British defence was beginning to take a steady

toll.

On the night of 2/3 September no fewer than twelve naval

airships, joined by four army craft flying from the Rhineland, set out for

London. Among the latter was a new Schutte-Lanz craft, SL-11, commanded by a

Captain Schramm. Approaching London from the north, SL-11 was brilliantly

illuminated by searchlights and surrounded by bursting anti-aircraft shells.

Schramm decided to turn away, but three night fighters were already converging

on him. Closest was Second Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson, who laced the

huge hull with two drums of incendiary and explosive ammunition, without

result. He then concentrated the fire of a third drum against one point near

the tail. A glow appeared inside the envelope, grew in intensity and suddenly

burst through in a roaring tongue of flame that briefly lit up another airship,

L-16, over a mile distant. Then, stern first, SL-11 crashed to earth near

Cuffley in Essex, her wooden Schutte-Lanz skeleton continuing to burn long

after the impact. There were no survivors. Robinson was awarded the Victoria

Cross.

Simultaneously, after a good run in which serious ground

fires had been started, L-33, one of the new ‘super-Zeppelins,’ sustained heavy

damage from anti-aircraft fire and was crippled by a night fighter flown by

Second Lieutenant Albert de Bathe Brandon. Her crew managed to land her near

Little Wigborough, then set her on fire before marching towards the coast in

the vain hope of finding a boat.

Mathy, now commanding L-31, took part in an eleven-strong

raid on London during the night of 1 October. Having dropped his bombs, Mathy

found himself under attack by four night fighters, one of which, piloted by

Second Lieutenant Wulstan J. Tempest, came in from above and set the ship

ablaze. The wreckage hit the ground at Potters Bar. Somehow, Mathy managed to

jump clear but died from his injuries almost immediately. His loss was keenly

felt throughout the airship service.

It was two months before naval Zeppelins appeared again in

British skies. They avoided London because of its heavy defences, and attacked

the North and Midlands instead. The raids were not a success and cost two

Zeppelins shot down in flames; L-34 over West Hartlepool and L-21 off

Lowestoft, having raided as far west as Newcastle-under Lyme.

For Count Zeppelin the airship was not the war-winning

weapon he had hoped it would be. Zeppelin raids against the United Kingdom

tailed away to 30 in 1917 and ten in 1918. Scheer’s memoirs record the final

days of the airship service.

A painful set-back occurred in January 1918 when, owing to

the spontaneous combustion of one of the airships in Ahlhorn, the fire spread

by the explosion spread to the remaining sheds, so that four Zeppelins and one

Schutte-Lanz machine were destroyed. All the sheds, too, were rendered useless.

After this, the fleet had, for the time being, only nine airships at its

disposal.

That was not quite the end of the of the Zeppelin story. The

Royal Navy had been developing the concept of the aircraft carrier for some

time and had finally produced a workable design by converting the light battle

cruiser Furious and fitting her with a flight deck. On 19 July 1918 she flew

off six Sopwith Camels which mounted a successful attack on the airship base at

Tondern, destroying Zeppelins L-54 and L-60.

On 5 August five Zeppelins, led by Captain Strasser himself

in the recently delivered L-70, mounted a final attack. L-70 was attacked by de

Havilland DH-4 fighters. Explosive ammunition blew a hole in the outer skin of

the ship’s stern. Within seconds flames spread rapidly along her length and the

blazing wreckage tumbled seawards from a height of some 15,000 feet. The

British pilots were horrified to watch the entire airship consume itself in

less than a minute. There were no survivors. Strasser was a well-liked

commander who had often accompanied his crews on their missions and had never

lost faith in the airship concept.

Six days later Zeppelin L-53 was carrying out a

reconnaissance patrol over the North Sea. No doubt the crew noticed, far below,

a destroyer travelling at speed. It did not attract a great deal of interest as

the airship was well beyond the range of its guns. For some unexplained reason

it seemed to be towing a lighter, although the details were unclear. Had L-53

been flying lower she would have seen one of the strangest anti-aircraft

systems ever devised, for on the lighter was a Sopwith Camel. The wind created

by the speed of the destroyer’s passage created just enough lift for the

biplane to become airborne. It took an hour before the Camel could reach a

height at which the airship could be engaged. At a range of 100 yards, drum

after drum was emptied into the Zeppelin’s belly, sending it into a fiery

death-dive. This was the last enemy airship to be destroyed by British fighters

during the war.

The huge size of the Zeppelins, caught in searchlight beams

or sliding across a gap in the clouds, coupled with their ability to hover,

produced widespread fear among the civilian population of Great Britain,

generated by the knowledge that their island was no longer a safe haven from

enemy activity, but it did not break their will to fight, as had been intended.

Zeppelins killed 528 people and wounded 1,156 more. They also caused enormous

damage, but it was spread across a very wide area. In addition, they tied down

17,340 men, hundreds of anti-aircraft guns, searchlights and barrage balloons,

plus numerous RNAS and RFC squadrons, all of which could have been usefully

employed in other theatres of war.

To crew a Zeppelin was to risk a particularly horrible

death. About 1,100 Zeppelin crewmen lost their lives, the second highest

proportion of those serving in any branch of the German armed services, the

highest being U-boat crews. John Terraine provides some idea of the scale of

Zeppelin losses in his book White Heat – The New Warfare 1914–18. He points out

that of the 130 airships employed by the German Army and Navy during the war,

only 15 existed when the Armistice was signed. Of the remainder, 31 were

scrapped, seven were wrecked by bad weather, 38 were accidently damaged beyond

economic repair, 39 were destroyed by enemy warships or land forces, while a

further 17 fell victim to the RFC or RNAS, either in the air or as a result of

bombing.