In their early years at Peenemünde, the German rocket

researchers had no difficulty in attracting the funds they needed. Money was

printed in large amounts and military expenditure for the Army now seemed to

have no limits.

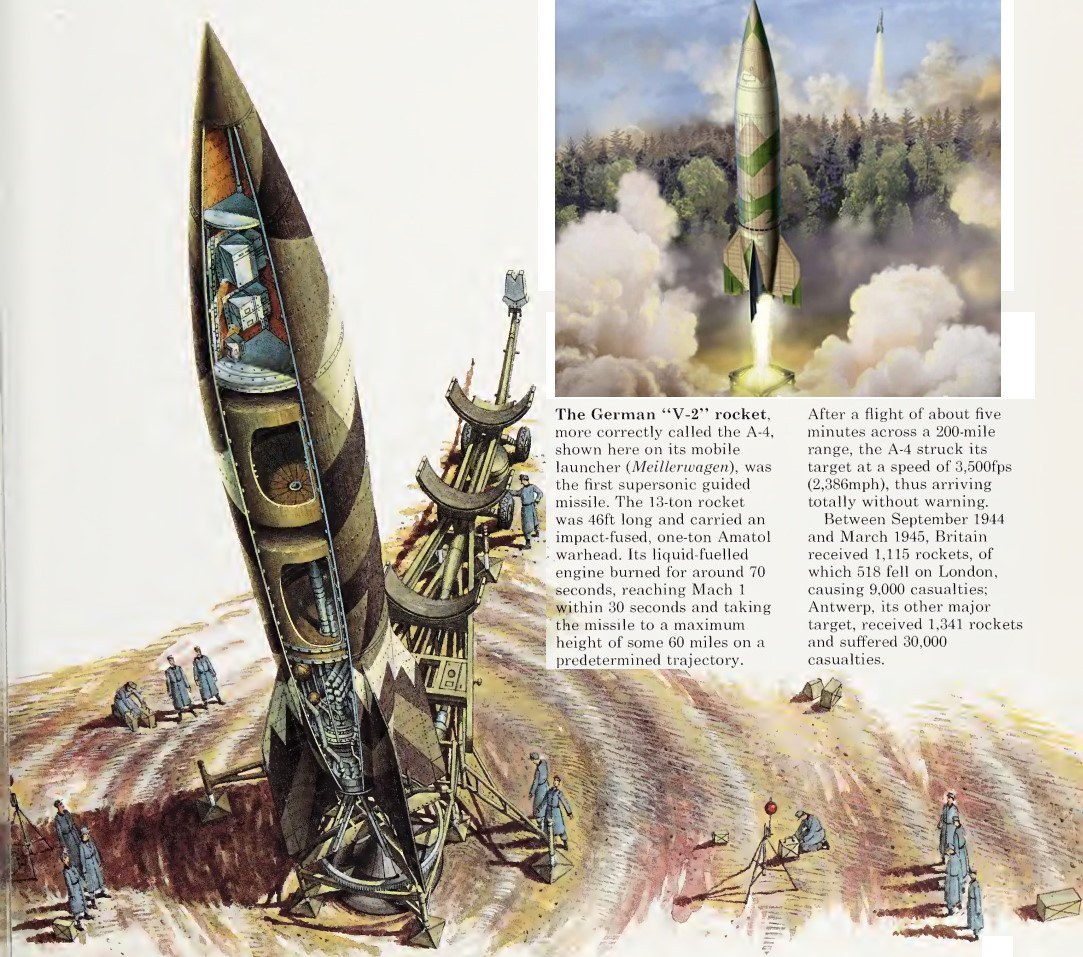

Von Braun was in his element at Peenemünde, and the design

of the great A-4 rocket proceeded apace. It was to be based on the successful

design of the A-5, with a redesigned control system and updated construction.

The A-5 had reached an altitude of 35,000ft (10,000m) in tests during 1938, and

the A-4 was designed with the benefit of the results of these pioneering tests.

But things changed when Hitler began to anticipate an early end to hostilities,

with Germany reigning supreme across Western Europe, and as a result research

at Peenemünde was reduced. In a scaled-down programme of research, the

engineers contented themselves by designing improved servo-control systems and

new, high-throughput fuel pumps were systematically developed. Rocket

development had essentially been put on hold.

Within two years the tide was turning, and the need for

rocket research began to re-emerge. Work on the A-4 picked up again and on 13

June 1942 the first of the new monster rockets was ready for test firing. The

rocket was checked and re-checked. Meticulous records were maintained of every

aspect of its functioning. It stood 46ft 1.5in (14.05m) tall, weighed 12 tons,

and was fuelled with methyl alcohol (methanol). The oxidant, liquid oxygen, was

pumped in just prior to launch. The pumps were run up to speed, ignition

achieved and the rocket rose unsteadily from its launch pad. In a billowing

cloud of smoke and steam it began to climb, rapidly gaining speed, and then –

at just the wrong moment – the propellant pump motor failed. The rocket

staggered for a moment and crashed back onto the launch pad, disintegrating in

a huge explosion. The technicians were terrified and were lucky to escape.

On 16 August 1942 a second A-4 was tested. Once again, the

fuel motor pump stopped working but this time it failed later in the flight,

after the rocket had already passed through the sound barrier. The third test

was a complete success. It took place on 3 October 1942 and this rocket was

fired out along the coast of Pomerania. The engine burned for over a minute,

boosting the rocket to a maximum altitude of 50 miles (80km). It fell to earth

119.3 miles (192km) from the launch pad. The age of the space rocket had arrived,

and the ballistic missile was a reality. The design of the A-4 rocket could now

be fine tuned and – given time – the complex design could be optimized for mass

production. The Nazis now had their new Vergeltungswaffe (‘retaliatory’ or

‘reprisal’ weapon). The term was important; although Hitler saw these as

weapons of mass destruction, he hoped that the world – instead of seeing him as

the aggressor – would regard him as simply responding to Allied attacks. The

‘V’ is sometimes translated into English as ‘vengeance’, but that is not right

as the term in German connotes reprisal. The first of such weapons was their

V-1 cruise missile, the ‘buzz-bomb’ and now they had the V-2. It would surely

strike terror into the hearts of those who challenged German supremacy.

Aspects of the design were refined and developed by teams in

companies including Zeppelin Luftschiffbau and Heinkel, and the final

production version of the V-2 was a brilliantly successful rocket. Over 5,000

would be produced by the Germans. The production model stood 46ft (14m) tall,

was 5ft 5in (1.65m) in diameter, and weighed over 5 tons of which 70 per cent

was fuel. The tanks held 8,300lb (3,760kg) of fuel and just over 11,000lb

(5,000kg) of liquid oxygen at take-off. The combustion chamber consumed 275lb

(125kg) per second, emitting exhaust gases at a velocity of 6,950ft/s

(2,200m/s). The missile was steered by vanes in the exhaust and could land with

an accuracy better than 4 per cent, or so claimed the designers. No metal could

withstand the intense heat, so these internal fins were constructed from

carbon. They ablated in the heat, but could not burn away rapidly due to the

lack of free oxygen and lasted long enough for the entire rocket burn. For the

time, the V-2 was – and it remains – an extraordinary achievement made in

record time.

Dörnberger tried to take full advantage of the success. Ever

since the United States had declared war on Germany on 8 December 1941, the

balance of power had begun to tip against the Nazis and Dörnberger knew the

time was ripe for official endorsement of his teams’ progress. Hitler had been

to see static tests of rocket motors at Kummersdorf but he had not been greatly

impressed by the noise, fire and smoke. These were so exciting to the rocket

enthusiasts – it was what rocketry was all about – but Hitler could not imagine

how these ‘boys’ toys’ could transmute into agencies of world domination and he

was reluctant to give the rocket teams the high priority they sought.

Dörnberger was frustrated by the bureaucracy and the lack of

exciting new developments. Some of the pressure had been temporarily relieved

from Dörnberger on 8 February 1942 when news reached him that the Minister for

Armaments and Munitions, Fritz Todt, had died at the age of 50. Todt was aboard

a Junkers Ju-52 aircraft on a routine tour when it crashed and exploded shortly

after take-off. Albert Speer was supposed to have been on the same flight, but

cancelled at the last minute. Speer was immediately appointed by Hitler to take

Todt’s place, and he was far more interested in what Dörnberger had to say.

Speer was a professional architect and had joined the Nazi party in 1931. He

had soon become a member of Hitler’s inner circle and had gained the Führer’s

trust after his appointment as chief architect. Speer clearly felt that Hitler

could be reconciled to the idea of the V-2 as progress continued.

As luck would have it, the new committee was put under the

charge of General Gerd Degenkolb, who disliked Dörnberger intensely. Von Braun

said at the time: ‘This committee is a thorn in our flesh.’ One can see why.

Degenkolb exemplified that other German trait, a talent for bureaucracy and

administrative complexity. He had been in a group including Karl-Otto Saur and

Fritz Todt, who espoused Hitler’s policy of being ‘not yet convinced’ by the

rocket as a major agent in military success. Degenkolb immediately began to

establish a separate bureaucratic structure to work alongside Dörnberger’s.

Details of the design of the V-2 rocket were reconsidered in detail by

Degenkolb’s new committee, and some of their untried new recommendations were

authorized without Dörnberger’s knowledge or approval.

Progress remained problematic even following the successful

launches. The Director of Production Planning, Detmar Stahlknecht, had set

targets for V-2 production which were agreed with Dörnberger – but which were

then unilaterally modified by Degenkolb. Stahlknecht had planned to produce 300

of the V-2 rockets per month by January 1944 – but in January 1943 Degenkolb

decreed that this total be brought forward to October 1943. Stahlknecht was

aiming for a monthly production target of 600 by July 1944; Degenkolb insisted

the figure be raised to 900 per month, and the date brought forward to December

1943. The success of the rocket was encouraging the policy makers to raise

their game, and their new targets seemed simply unattainable.

The Capitalist dream

At this point, Dörnberger was presented with a startling new

prospect. He learned of a bizarre idea to capitalize on the sudden enthusiasm

for the new rockets. He was told that it was being proposed to designate

Peenemünde as a ‘land’ in its own right. It would be jointly purchased by major

German companies like AEG and Siemens who would pay more than 1,000,000

Reichsmarks for the property and then charge the Nazi government for each

missile produced. AEG, in particular, were highly impressed by the telemetry

developed for the V-2 rocket and recognized that it had far-reaching

implications and considerable market potential.

The guidance systems were remarkably advanced. They had been

developed by Helmut Gröttrup, working alongside Von Braun, though there was

little friendship between the two. Dörnberger fought to have Peenemünde

maintained as an army proving ground and production facility, and won the

battle only after bitter negotiations. This had been a narrow victory for

Dörnberger, and was one that he would have been unlikely to win without the

support of Speer.

Three sites were immediately confirmed for the production of

the new rockets: Peenemünde, Friedrichshafen and the Raxwerken at Wiener

Neustadt. Degenkolb issued orders at once, but he failed to see that the senior

staff were not available in sufficient numbers to train and organize production

on such a rapidly expanding scale. Degenkolb refused to be challenged and

insisted that production begin immediately – and, when the engineers explained

the impossibility of the task at such short notice, Degenkolb issued orders

that they be imprisoned if his schedule was not met. Clearly, he meant

business.

Although Degenkolb saw Von Braun as a personal rival, and

someone he disliked, he recognized that his participation was crucial to the

success of the rocket development. Others knew this too. At one stage, Von

Braun had even been arrested by the authorities under the suspicion that his

covert purpose was not the bombardment of foreign cities for the benefit of the

Fatherland, but that he was secretly planning to develop rockets for space

exploration at government expense. At first, Von Braun’s protests came to

nothing and a lengthy bureaucratic enquiry seemed inevitable, until Dörnberger

intervened to say that, without Von Braun, there could be no further progress.

At this, Von Braun was released and sent back to his work. Dörnberger reported

his frustrations with a lack of progress towards full production. Speer

understood that the heavy-handed administrative interference of Degenkolb had

introduced an unnecessary hold-up (reckoned by Dörnberger to be a delay of 18

months) and promised to remove him if it would help.

In the event, Degenkolb survived because of the influence of

Fritz Todt’s long-standing friend, Karl-Otto Saur. Saur himself had a

remarkable instinct for survival and, after the war, he was used as a key

witness for the prosecution on behalf of the American authorities and was

subsequently released. The fact that Karl-Otto Saur was designated by Hitler to

replace Speer as Minister for Armaments was not a sufficient crime for him to

be tried as a war criminal, and he eventually set up a publishing house back in

Germany named Saur Verlag. The company survives to this day publishing

reference information for librarians – a curious legacy from World War II.

Wernher von Braun (center), the technical director of the Peenemünde Army Research Center with German officers at Peenemünde, March 21, 1941. The British attempt to incapacitate the leadership of the German rocket program was unsuccessful. Von Braun and most of the important German scientists survived Operation Hydra.

The remaining serious challenger to the V-2 was the

Luftwaffe’s buzz-bomb, the V-1. Its proponents pointed out that it was cheap to

fly, economic to fuel, easy to produce in vast numbers and surely a far better

candidate for support than the costly and complex V-2. Dörnberger argued

strongly in favour of his own project. The V-1 needed a launch ramp, whereas

the V-2 could be launched from almost anywhere it could stand. The flying bomb

was easy to detect, shoot down or divert off course, whereas a rocket was

undetectable until after it had hit. In the end the Nazi authorities were

persuaded by both camps and the two weapons were ordered into mass production.

Nonetheless, the delays remained an obstacle to progress, and by the summer of

1943 – with Degenkolb’s production target of 900 per month looming ever closer

– the engineers protested that their highly successful engine was still not

ready for manufacture in large amounts by regular engineers.

Once again there were conflicting interests and opposing

policies. Adolf Thiel, senior design engineer on the V-2, protested that mass

production was not likely to be achieved before the war had come to its natural

conclusion. Friends of Thiel reported he was close to a nervous breakdown, and

wanted to stop work at Peenemünde and retire to an academic career at

university. However, Von Braun remained obdurately convinced that they were

close to success and, on balance, Dörnberger sided with that view.

Watching from London

Meanwhile, British Intelligence was watching. A major

breakthrough for the British came on 23 March 1943. A captured German officer,

General Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, provided timely information that the Allies

would find of crucial importance. Back on 29 May 1942 the Nazi

Lieutenant-General Ludwig Crüwell had flown to inspect German operations in

Libya when his pilot mistook British soldiers for Italian troops and he landed

the plane alongside them. Crüwell was taken prisoner and on 22 March 1943 he

was placed in a room with General Von Thoma. The room was bugged, and their

muffled conversation was partly overheard by the eager British agents,

listening in the next room. The notes were recorded in the secret Air

Scientific Intelligence Interim Report written up on 26 June 1943, and now held

in the archives at Churchill College, University of Cambridge, England:

No progress whatsoever can have been made in this rocket

business. I saw it once with Field Marshall [Walther von] Brauchitsch. There is

a special ground near Kummersdorf. They’ve got these huge things which they’ve

brought up here… They’ve always said that they go fifteen kilometres up into

the stratosphere and then … you only aim at an area. If one was to … every few

days … frightful! The major there was full of hope – he said, ‘Wait until next

year and the fun will start. There’s no limit [to the range]…

Further substantiation came in June 1943, when a resourceful

Luxembourger named Schwaben sent a sketch of the Peenemünde establishment to

London in a microfilm through a network of agents known as the Famille Martin.

This fitted well with the other reports that had been arriving, including

eye-witness accounts and notes smuggled out from secret agents about activity

at Peenemünde. The intelligence service kept meticulous records of the reports

of vapour trails, explosions and occasional sightings that were relayed back to

London from those witnesses who were anxious to see an end to Nazi tyranny.

Churchill appointed his son-in-law, Duncan Sandys MP, to head a committee to

look further into the matter and on 12 June 1943 an RAF reconnaissance mission

was sent to fly over the site at high altitude and bring back the first images

of what could be seen at Peenemünde. The unmistakable sight of rockets casting

shadows across the ground could be picked out in the images. Measurements

suggested to the British that the rocket was about 38ft (11.5m) long, 6ft

(1.8m) in diameter and had tail fins. The intelligence report estimated the

mass of each rocket must be between 40 and 80 tons. It was guessed that there

might be 5 or 10 tons of explosives aboard.

This was partly right, and partly a gross exaggeration. The

V-2 was actually 46ft (14m) long and 5ft 5in (1.65m) in diameter, so the

measurements calculated by the British were reasonable estimates. But the

weight of the missile was wildly over-estimated – rather than 40 tons or more,

it weighed just under 13 tons and carried 2,200lb (980kg) of explosive rather

than ‘up to 10 tons’ of the British estimates. A ‘rough outline’ drawing of the

rocket was prepared for this report and it looks more like a torpedo. Perhaps

the missile as drawn lacked its 7.5ft (2.3m) warhead nose cone. In that case,

the dimensions were surprisingly accurate – though there is no accounting for

the gross over-calculation of the weight.

Although the guesswork about the rocket’s weight was wrong,

the comments that R. V. Jones added to the secret intelligence report of 26

June 1943 show a remarkably clear analysis of Germany’s position at the time.

The evidence shows that … the Germans have for some time

been developing a long-range rocket at Peenemünde. Provided that the Germans

are satisfied with Peenemünde’s security, there is no reason to assume the

existence of a rival establishment, unless the latter has arisen from

inter-departmental jealousy.

Almost every report points to the fact that development can

hardly have reached maturity, although it has been proceeding for some time.

If, as appears, only three rockets were fired in the last three months of 1942,

with two unsuccessful, the Germans just then have been some way from success and

production.

At least three sorties over Peenemünde have now shown one

and only one rocket visible in the entire establishment and one sortie has

perhaps shown two. Supposing that the rockets have been accidentally left out

in the open or because the inside storage is full, then the chances are that

the rocket population is less than, say, twenty. If it were much greater, then

it would be an extraordinary chance that this number should always be one

greater than storage capacity. Therefore the number of rockets at Peenemünde is

small, and since this is the main seat of development, the number of rockets in

the Reich is also likely to be relatively small…

Since the long-range rocket can hardly have reached

maturity, German technicians would probably prefer to wait until their designs

were more complete. If, as seems very possible, the genius of the Führer

prevails over the judgement of the technicians, then despite everything the

rocket will shortly be brought into use in its premature form.

Jones drew this conclusion: ‘The present population of

rockets is probably small, so that the rate of bombardment [of London] would

not be high. The only immediate counter measure readily apparent is to bomb the

establishment at Peenemünde.’

Jones was right, and plans for a massive bombing raid began

at once. Three days later, on 29 June 1943, a meeting was convened at the

Cabinet War Room at which Duncan Sandys revealed the contents of the

photographs. He had short-circuited R. V. Jones’s connections with the photo

labs and insisted that they all be sent first to him. One of those attending

the meeting was Professor Frederick Lindemann, Viscount Cherwell, who

immediately poured scorn on the idea of a rocket base. Lindemann was a

German-born physicist and Churchill’s chief scientific adviser. He said at the

meeting that a rocket weighing up to 80 tons was absurd. The rockets, he

insisted, were an elaborate sham; the Germans had mocked them up to frighten

the British and lead them on a false trail. It was nothing but an elaborate

cover plan. After his analysis, which left the officials in the room sensing

that a dreadful mistake was being made, Churchill turned to R. V. Jones and

said that they would now hear the truth of the matter. Jones was crisp and to

the point. Whatever might be the remaining questions over the details of these

missiles, said Jones, it was clear to him that the rockets were real – and they

posed a threat to Britain. The site must be destroyed. The idea of sending

further reconnaissance flights was quickly dismissed, for it could alert the

Germans to the fact that the Allies had discovered the site.

Peenemünde was too far away to be in contact by radio, and

out of range of the fighters; so the Allied bombers would be completely

unprotected. German fighters would soon be on the scene, and heavy Allied

losses were likely. The conclusion was that the heaviest bombing would be

arranged, and it would take place on the first night that meteorological

conditions were suitable. The attack was code named Operation Hydra.

Aerial photograph of Peenemunde (AIR 34/184) –

Transcript Peenemunde Site Plan/Target Map, (AIR 34/632)

Operation Hydra, the raid on Peenemünde. Targets shown

are

A:

Experimental station

B: Factory

workshops

C: Power

plant

D:

Unidentified machinery

E:

Experimental establishments

F: Sleeping

and living quarters

G: Airfield

Date: April 1943

Operation Hydra

On 8 July 1943 Hitler was shown an Agfacolor film of the

launch of a V-2 and was finally convinced that the monster rocket could win him

back the advantage. Having been sceptical, Hitler was now an enthusiastic

supporter. He immediately decided that new launch bases would be needed across

the northern coast of continental Europe in order to maximize the range of the

rockets and the number of launches that Germany could make against Britain. He

also ordered that the production of the V-2 was now to be made a top priority.

Hitler believed that with these rockets he could turn the tide of war against

the Allies. The Germans were busy working to comply with orders to construct a

production line at the Peenemünde Army Research base just as the Royal Air

Force was instructed to launch Operation Hydra to destroy the establishment.

The planning of Operation Hydra was meticulous. Bombing

would be carried out from 9,000ft (about 3,000m; normally bombing raids were

from twice as high), and practice runs over suitable stretches of British

coastline were quickly arranged. The accuracy improved greatly during the

practice sessions, an error of up to about 1,000 yards (900m) improving to 300

yards (270m). None of the aircrew were told the true nature of their target;

they were informed that the installation was a new radar establishment that had

to be destroyed urgently. By way of encouragement to be thorough on the first

raid, they were also told that repeat attacks would be made, regardless of the

losses, if they did not succeed first time. Meanwhile, a decoy raid was

arranged, code named Operation Whitebait. Mosquito aircraft were to be sent to

bomb Berlin prior to the raid on Peenemünde in the hope of attracting German

fighters to the area. Further squadrons were meanwhile sent to attack nearby

Luftwaffe airfields to prevent German fighters taking to the air over

Peenemünde. As the attack began, a master bomber, Group Captain J. H. Searby,

would circle around the target to call in successive waves of bombers.

On the night of 17 August 1943 there was a full moon, and

the skies were clear. At midnight the raid began, and within half an hour the

first wave was heading for home. Over the target, however, there was some light

cloud and the accuracy of the first bombs was poor. Guns from the ground were

returning fire, and a ship off-shore brought flak to bear on the bombers, but

no fighters were seen. The second wave of Lancasters was directed at the

factory workshops and then at 12.48am the third and final wave attacked the

experimental workshops. This group of Lancaster and Halifax bombers overshot

the target and most dropped their bombs half a minute late, so their bombs

landed in the camp where conscripted workers were imprisoned. By this time

German fighter aircraft were arriving, but they were late and losses to the

British bombers were less than 7 per cent.

However, the laboratories and test rigs were damaged – and

the Germans now knew, with dramatic suddenness, that their elaborate plans were

known to the Allies. On the brink of realization, the plans to manufacture the

V-2 at Peenemünde had to be abandoned. The Germans decided to fool the Allies

into thinking that they had caused irreparable damage, so they immediately dug

dummy ‘bomb craters’ all over the site, and painted black and grey lines across

the roofs to look like fire-blackened beams. Their intention was to fool any

reconnaissance flights into believing the damage was much worse than it was,

thus convincing the British that further raids were unnecessary. The British

still had one further element of retaliation, however; a number of the bombs

were fitted with time delay fuses and exploded randomly for several days after

the raid. They did not cause much material damage, but the continued detonations

delayed the Germans from setting out to move equipment from the site.