Due to the largely accepted idea that `the Arab conquests

were made possible by the opponents’ weaknesses rather than by the power of the

nascent Muslim armies’, pre-conquest Arab forces have received very limited

attention. How such forces were brought together, organised and led have yet to

be studied in any real detail. The main reason for this is the state of the

source material. Unsurprisingly, aside from their deployments as scouts within

their own armies, the Romans and Persians are silent about the military

organisation of the Muslims, while the Arab accounts present their own

problems. Their religious nature often attributes victory to the convictions of

those involved and their submission to the Will of God rather than military

organisation, skill and bravery. Events can be distorted to further an agenda

or by the employing of literary topoi to bolster an otherwise unknown part of

the narrative. Later Islamic sources also tended to portray their predecessors

in anachronistic terms, projecting the social, political and military

organisation of their periods back onto that of early Islam, imposing `a false

sense of organisation and method on military manoeuvres, which were, in

reality, much more chaotic’. Such an abundance of potential problems makes any

attempt to reconstruct any aspect of the early Muslim military fraught with

danger and undermines any chances of firm conclusions.

The earliest Muslim military actions would have been a

combination of caravan looting and raids against neighbouring Bedouin tribes to

bolster resources, seek vengeance, discourage potential enemies, claim

strategic points or enforce religious conversion. Such raids reflected the

enemies that the fledgling Muslim army faced and how rare true pitched battle

was in Arab warfare. They also `contributed a great deal to the Muslim

community in terms of wealth, experience and the achievement of political and

strategic goals.’ How- ever, as the enemies of Islam grew in size and stature

such an unstructured army would not have been successful, forcing Muhammad and

his advisers to improvise and incorporate a more structured approach to

administration and organisation.

Perhaps the most immediate change brought about by the rise

of Islam came in the realm of army leadership. Aside from tribal leaders, who

owed their status to their ancestry and personal success, pre-Muslim Arab war

parties had little in the way of a command structure. Under Islam, ultimate

military authority, itself something of a novelty across much of the Arabian

Peninsula, lay with Muhammad and his caliphal successors; however, as campaigns

became further removed from Medina, it became necessary to appoint individuals

to military command. In choosing men of certain tribes for certain commands,

the Prophet and his caliphal successors demonstrated an under- standing of

tribal politics while the appointments of men like Khalid and Amr, later

converts to Islam, showed that Muhammad was willing to promote military talent

ahead of standing within the Muslim community. It should also be pointed out

that the repeated instances of rapid communication and dictation of military

movements attributed to the caliphs in Medina should be treated with

scepticism. Some major redeployments may have been ordered by the caliphs but

the majority of decisions will have been taken on the ground by those men the

caliph had entrusted to achieve the strategic objectives of the campaign.

The leadership of skilled individuals such as Khalid may

have encouraged the emergence of a more structured military beyond its tribal

make-up. The Muslim army does seem to have used similar formations to late

antique Roman and Persian armies with right and left wings and a centre.

Advance guards, vanguards and rearguards are also mentioned. An even more

organised structure is recorded at the Battle of Qadisiyyah, where the Muslim

commander, Sa’d b. Abi Waqqas, had divided his force into sub-groups of ten.

However, it is likely that such subdivisions were superimposed on the past by

later writers for, even with this interposing of a religio-political hierarchy

and the appearance of numerous independent corps during the Ridda Wars, there

was little sign of what would be described as a regular, even semi-permanent

army.

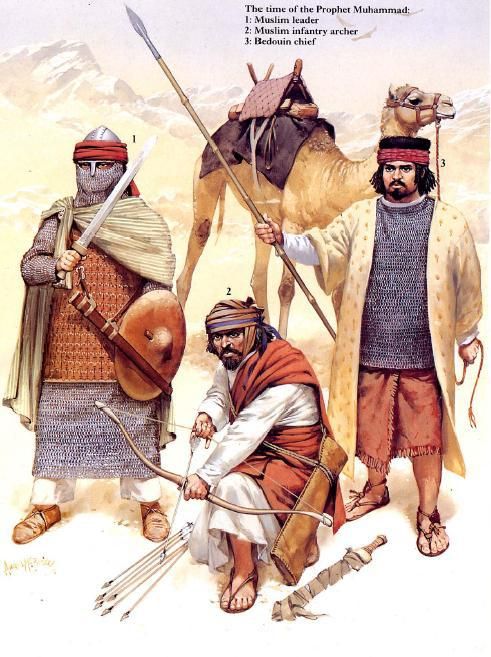

As with other antique forces, the early Islamic army was

largely divided into cavalry and infantry. However, a tentative warning must be

sounded regarding the blurring of the two as cavalrymen would often fight

dismounted and infantry could be transported on horse or camel. The vast

majority of Arab horse of the early period was light cavalry used as raiders

and skirmishers or as lancers, rather than horse archers or heavy cavalry such

as the cataphracts of the Roman and Persian armies. It is also worth noting

that horses were not abundant in Arabia; a fact that might explain why Arab

cavalry relied more on mobility and skirmishing to avoid costly casualties both

in terms of men and horses. It might also partly explain why it was infantry

that bore the brunt of the fighting in Arab warfare. The core of the Muslim

infantry was made up of swordsmen who carried a straight, hilted blade – the

sayf – that was used for thrusting and slashing. They also made use of

iron-tipped spears and javelins. Another sizeable part of the Muslim infantry

used the archery skills that hunting with a bow honed. The Arab bow seems to

have been a smaller variant than its Persian counterpart but it is possible

that the more rapid fire offered by the smaller bow allowed Muslim archers to

more effectively shield their infantry and cavalry.

Little physical material remains of early Muslim defensive

equipment, and that which does survive is difficult to date or source. Muslim

sources rarely speak of military equipment unless the articles themselves were

famous, such as the swords, shields, bows and lances of Muhammad, and it is

likely that most Muslim soldiers will have fought without the full military

panoply. Instances of Arab chainmail armour do survive, although how widespread

its use was in the Muslim army before the conquests is difficult to gauge. Mail

was expensive to buy or make, meaning that perhaps only the richest Arab

soldiers or those who had served in the Roman or Persian armies will have had

such armour. Helmets may have been less prevalent before the conquests with a

hood of mail called a coif being used instead to protect the head. Shields were

carried by both cavalry and infantry and, while they are not well described in

the sources, the few surviving descriptions suggest that the normal Arab shield

was wooden or leather made into a `small disk, certainly less than a metre in

diameter’.

A less significant section of the Muslim army was that given

over to siege engines. Most Arab settlements had some kind of fortifications but

few were prepared for a prolonged siege so the Muslims will have had little

experience of siege warfare. Siege equipment such as the swing-beam manjaniq,

similar to the trebuchet of Europe, is seen in later Muslim armies; however,

the extent to which such machines were used by the Arabs of the 630s is difficult

to say. A manjaniq was deployed during the siege of Ta’if in 630, although its

lack of success against modest defences is telling, which may explain why such

machines were more likely to be used as anti-personnel weapons rather than

against fortifications. There is also no evidence for the torsion-based

predecessors of such machines, which further suggests that Arab siege craft was

largely basic. However, while it is easy to downplay the siege abilities of

tribal societies such as the Arabs and the Avars, they proved themselves to be

quick learners and highly adaptive to such situations. The Arabs in particular

seem to have quickly realised that `victory often depended on preliminary

political success rather than sheer military power’. With this realisation,

Muhammad, his successors and their commanders proved themselves adept at

separating a settlement from its allies through negotiation or blockade and

then offering `protection and toleration in return for a fixed tribute’. Through

such a combination, even the most major of cities – Damascus, Ctesiphon,

Jerusalem, Antioch and Alexandria – would prove to be within the grasp of

Muslim forces.

With the advent of Islam’s temporal power, a vague outline

of a recruiting process begins to emerge. Volunteers or prescribed tribes

gathered at Medina or at a predetermined site, were formed into an army and

then sent into the field. Most of the muqatila – `fighting men’ – who served in

the Arab armies were of Bedouin origin, which is unsurprising given that

raiding, fighting and familiarity with riding, spears, swords and archery were

integral parts of their daily lives. However, the rapid expansion of the Muslim

community brought with it a wider spectrum of potential soldier. There is some

evidence that the Muslims equipped some of their more settled or poorer members

to fight. Alliances with Jewish, Christian and other non-Muslim tribes played

major roles in the military survival and successes of Muhammad and his `Umma in

its earliest years. Clients and slaves were also present in Muslim armies with

the likelihood being that not all of them were Arabic in origin. Defection also

added to the military strength of the Muslim armies while at the same time

undermining its opponents.

The recorded sizes of Muslim armies are often hard to accept

due to their seemingly formulaic nature. They are usually portrayed as being

particularly small in number throughout their earliest history, such as raiding

parties featuring forces numbering less than 100. However, the rapidity with

which Muhammad was able to field armies of up to and beyond 10,000 might be

cause for some suspicion – 300 at Badr; 700 at Uhud; 3,000 at Mu’ta, 10,000 at

Mecca and 12,000 at Hunayn. During the attacks on Roman and Persian territory,

the Muslim armies are also regarded as being on the small side with perhaps as

few as 6,000 fighting at Qadisiyyah and the garrisons in southern Mesopotamia

perhaps only numbering up to 4,000.

This seeming paucity of Arab soldiers must also be tempered

by the exaggerated reporting of the armies of their Roman and Persian foes. The

Great Powers probably maintained a numerical superiority over the Muslims but

it was almost certainly not as overwhelming as the suggestions of the Muslim

sources, which at times attempt to put armies in the order of hundreds of

thousands in the field. Many of the proposed numbers for Muslim armies need to

be viewed from a contemporary perspective. The previous two centuries or more

had seen a marked decline in the size of armies deployed by the Romans and

Persians; so much so that Mauricius considered an army of 5,000-15,000 to be

well proportioned and 15,000-20,000 to be large. The fact that the Muslims may

have been able to field a force of anything between 20,000 and 40,000 at Yarmuk

suggests that the numerical gradient they faced was not as severe as is usually

thought.

However, in spite of some advances compared to the

pre-Islamic period, the early Muslim military remained simplistic. Aside from

perhaps the greater desert mobility that camels provided, they were at a

technological disadvantage to their Roman and Persian adversaries and, while

perhaps not overly serious, they were at a numerical disadvantage too.

Organisationally, even after the successes of the Ridda Wars, the Muslim army

was still closer to a tribal war party than it was to the professional forces

that the Romans could field. They were not paid nor provided any benefits and

their enrolling in the army was not recorded in any way. However, these men

were fuelled by the prospect of booty, encouraged by the martial bonds of their

tribe and buoyed by the morale offered to them by their religion, and, once

they were brought together under the Muslim banner and led in battle by a cadre

of skillful practitioners of war, they were to prove an increasingly

irresistible force. And in the 630s, the Great Powers were about to find out

how devastating such a force could be.