Cadorna issued an order of the day, warning that the only

choice was victory or death. The harshest means would be used to maintain

discipline. ‘Whoever does not feel that he wins or falls with honour on the

line of resistance, is not fit to live.’ He elaborated his instructions to the

Second and Third Armies for an eventual retreat, and put the Carnia Corps and

the Fourth Army on notice to retire beyond the River Piave.

What forced his hand was the loss that evening of Gran

Monte, a summit west of Stol. At 02:50 on the 27th, he ordered the Third Army

to retreat to the River Tagliamento. The same order went out to the Second Army

an hour later. Yet 20 of the Second Army’s divisions were still in reasonable

order, withdrawing from the Bainsizza and Gorizia. Cadorna’s priority should

have been the safe retirement of these divisions – more than 400,000 men –

behind the River Tagliamento. In his mind, however, the Second Army in its

entirety was guilty. Perhaps this explains his decision to make the Second Army

use only the northern bridges across the Tagliamento, reserving the more

accessible routes for the ten divisions of the Third Army, which retreated ‘in

good order, unbroken and undefeated’, burning the villages as well as its own

ammunition dumps as it went, so that ‘the whole countryside was blazing and

exploding’. This question of the bridges was critical, for the bed of the

Tagliamento is up to three kilometres wide and the river was high after the

rain, hence impassable by foot.

Between the Isonzo and the Tagliamento, the decomposing

Second Army was left to its own devices. In the absence of proper plans for a

retreat, there was nothing to arrest its fall. As commanding officers melted

away in the tumult, key decisions were taken by any officer on hand, using his

own impressions and whatever scraps of information came his way. According to a

captain who testified to the Caporetto commission, the soldiers appeared to

think the war was over; they were on their way home, mostly in high spirits, as

if they had found the solution to a difficult problem.

A minor episode described in a letter to the press in 1918

illustrates the point. A lieutenant told the surviving members of his battalion

that they would counter-attack soon, orders were on the way. Instead of orders,

a sergeant came cycling along the road. When they stopped him and asked what

was going on, he said the general and all the other bigwigs had run away.

‘Then we’re going too,’ someone said, and we all shouted

‘That’s right, we have had enough of the war, we’re going home.’ The

lieutenant said ‘You’ve gone mad, I’ll shoot you’, but we took his pistol

away. We threw our rifles away and started marching to the rear. Soldiers

were pouring along the other paths and we told them all we were going home

and they should come with us and throw their guns away. I was worried at

first, but then I thought I had nothing to lose, I’d have been killed if I’d

stayed in the trenches and anything was better than that. And then I felt

so angry because I’d put up with everything like a slave till now, I’d

never even thought of getting away. But I was happy too, we were

all happy, all saying ‘it’s home or prison, but no more war’.

All along the front, variants on this scene convey a sense

that a contract had been violated, dissolving the army’s right to command

obedience. Nearly 400 years before, in his ‘Exhortation to liberate Italy from

the barbarians’, Niccolò Machiavelli had warned his Prince that ‘all-Italian

armies’ performed badly ‘because of the weakness of the leaders’ and the

unreliability of mercenaries. The best course was ‘to raise a citizen army; for

there can be no more loyal, more true, or better troops’. They are even better,

he added, ‘when they find themselves under the command of their own prince and

honoured and maintained by him’. Machiavelli the great realist would not have

been surprised by the size of the bill that Cadorna was served after

dishonouring his troops so consistently, and neglecting their maintenance so

blatantly, for two and a half years.

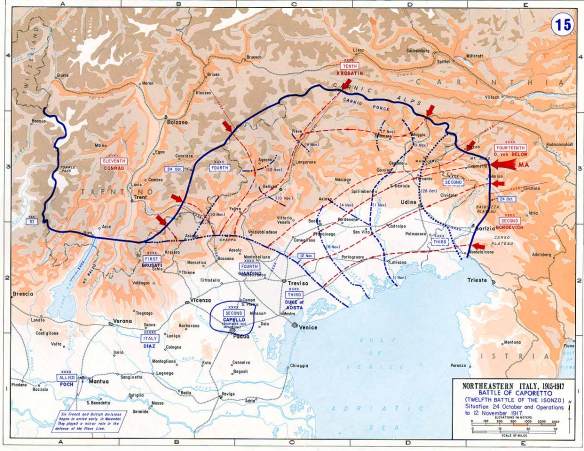

On the third day of the offensive, the Austrians and Germans

gave the first signs that they would not convert a brilliant success into

crushing victory. Demoted in spring 1917 from chief of the general staff to

commander on the Tyrol front, Field Marshal Conrad von Hötzendorf had to sit

and watch as von Below’s Fourteenth Army turned the tables on the hated enemy.

Now he called for reinforcements so he could attack the Italian left flank. At

best, Cadorna’s Second, Third and Fourth Armies and Carnia Corps would be

trapped behind a line from Asiago to Venice, perhaps forcing Italy to accept an

armistice. At the least, the Italians would be too distracted by the new threat

to establish viable lines on the River Tagliamento.

Although Conrad’s reasoning was excellent, the Germans were

not ready to increase their commitment or let the Austrians pull more divisions

from the Eastern Front. Any Habsburg units which might be released by Russia’s

virtual withdrawal from the war had to be sent to the Western Front, where the

Germans were hard pressed by the British in the Third Battle of Ypres

(Passchendaele). All Conrad got were two divisions and a promise that any

others no longer needed on the Isonzo would be sent to the Trentino for an

offensive by five divisions, to commence on 10 November. But five divisions

were pathetically few for the task, and 10 November would be too late.

Cadorna’s enemies had not expected such a breakthrough. As

late as the 29th, Ludendorff stated that German units would not cross the

Tagliamento. By this point, Boroević’s First Army (on the Carso) and Second

Army (around the Bainsizza) should have been storming after the Italian Third

Army. This did not happen, due to bad liaison between commanders, exhaustion,

and the temptations of looting. As a result, the Third Army crossed the

Tagliamento in good order at the end of October. Both divisions of the Carnia

Corps also reached safety with few losses. Von Below would characterise the

Austrian Tenth Army, that should have outflanked the Carnia Corps, as not ‘very

vigorous in combat’.

On the afternoon of the 27th, the Supreme Command decamped

from Udine to Treviso. Cadorna did not leave a deputy to organise the retreat.

Was this an oversight or a logical expression of his belief that he was

irreplaceable? Or was he punishing soldiers who had, as he believed, freely

chosen not to fight? Let the cowards and traitors of the Second Army make their

own shameful ways to the Tagliamento; they had forfeited the right to

assistance.

By the following morning, the Supreme Command was installed

in a palazzo in Treviso, more than 100 kilometres from the front. Over

breakfast in his new headquarters, the chief talked about the art and landscape

of Umbria, impressing his entourage with his serenity, a mood that presumably

owed something to the King’s and the government’s affirmations of complete

confidence in his leadership. (Meanwhile the enemy reached the outskirts of

Udine, finding them ‘almost deserted with broken windows, plundered shops, dead

drunk Italian soldiers and dead citizens’.) Before lunch Cadorna released the

daily bulletin, blaming the enemy breakthrough on unnamed units of the Second

Army, which had ‘retreated contemptibly without fighting or surrendered

ignominiously’. Realising how incendiary these allegations were, the government

watered down the text. It was too late: the original version had gone abroad

and was already filtering back into Italy.

Late on the 28th, the enemy crossed the prewar border into

Italy. The Austrian military bulletin was gleeful: ‘After five days of

fighting, all the territory was reconquered that the enemy had laboriously

taken in eleven bloody battles, paying for every square kilometre with the

lives of 5,400 men.’ The Isonzo front ceased to exist. By the 29th, the Second

and Third Armies were being showered with Austrian leaflets about Cadorna’s

scandalous bulletin. ‘This is how he repays your valour! You have shed your blood

in so many battles, your enemy will always respect you … It is your own

generalissimo who dishonours and insults you, simply to excuse himself!’

An order on 31 October authorised any officer to shoot any

soldier who was separated from his unit or offered the least resistance. This

made a target of ten divisions of the Second Army. The worst abuses occurred

near the northern bridges over the Tagliamento, where commanders who had

abandoned their men days earlier saw a chance to redeem themselves.

The executions at Codroipo would provide a climactic scene

in the only world-famous book about the Italian front: Ernest Hemingway’s A

Farewell to Arms.

The wooden bridge was nearly three-quarters of a mile

across, and the river, that usually ran in narrow channels in the wide stony

bed far below the bridge, was close under the wooden planking … No one was

talking. They were all trying to get across as soon as they could: thinking

only of that. We were almost across. At the far end of the bridge there were

officers and carabinieri standing on both sides flashing lights. I saw them

silhouetted against the skyline. As we came close to them I saw one of the

officers point to a man in the column. A carabiniere went in after him and came

out holding the man by the arm … The questioners had all the efficiency,

coldness and command of themselves of Italians who are firing and are not being

fired on … They were executing officers of the rank of major and above who were

separated from their troops … So far they had shot everyone they had

questioned.

The narrator is Lieutenant Frederic Henry, an American

volunteer with the Second Army ambulance unit. Caught up in the retreat from

the Bainsizza, he is arrested on the bridge as a German spy. As he waits his

turn with the firing squad, Henry escapes by diving into the river. ‘There were

shots when I ran and shots when I came up the first time.’ He is swept

downstream, away from the front and out of the war. Immersion in the

Tagliamento breaks the spell of his loyalty to Italy. ‘Anger was washed away in

the river along with any obligation … I had taken off the stars, but that was

for convenience. It was no point of honour. I was not against them. I was

through … it was not my show any more.’

The deaths in Hemingway’s chapter on Caporetto involve

Italians killing each other. The enemy guns are off-stage, heard but not seen,

while German troops are glimpsed from a distance, moving ‘smoothly, almost

supernaturally, along’ – a brilliant snapshot of Italian awe. Henry shoots and

wounds a sergeant who refuses to obey orders; his driver, a socialist, then

finishes the wounded man off (‘I never killed anybody in this war, and all my

life I’ve wanted to kill a sergeant’). The driver later deserts to the

Austrians, a second driver dies under friendly fire, then there is the scene at

the Tagliamento. It is a panorama of internecine brutality and betrayal, devoid

of heroism. With the army self-destructing, nothing makes sense except Henry’s

passion for an English nurse. Caporetto is much more than a vivid backdrop for

a love story: it is an immense allegory of the disillusion that, in Hemingway’s

world, everyone faces sooner or later. Henry’s desertion becomes a grand

refusal, a nolo contendere untainted by cowardice, motivated by a

disenchantment so complete that it feels romantic: a new, negative ideal which

holds more truth than all the politics and patriotism in the world.

By 1 November, there were no Italian soldiers east of the

Tagliamento. Cadorna had hoped to hold the line long enough to regroup much of

the Second Army. Instead, early next day, an Austrian division forced its way

across a bridge on the upper Tagliamento that had not been completely

destroyed. This gave heart to a German division trying to ford the river

further south. When both bridgeheads were consolidated, Cadorna faced the

danger that most of his Second Army and all of his Third Army could be

enveloped from the north. On the morning of 4 November, he ordered a retreat to

the Piave line. The Austro-German commanders redefined their objectives: the

Italians should be driven across the River Brenta – beyond Venice! However,

Ludendorff was not yet convinced. By the time he changed his mind, on 12

November, approving a combined attack from the Trentino, the Italians had

stabilised a new line on the River Piave and Anglo-French divisions were

arriving from the Western Front.

Haig commented privately on 26 October that, ‘The Italians

seem a wretched people, useless as fighting men but greedy for money. Moreover,

I doubt whether they are really in earnest about this war. Many of them, too,’

he added for good measure, ‘are German spies.’ Although these prejudices were

widely shared in London and France, the Allies were shocked by the speed of the

disintegration and alarmed at its potential impact: if Italy were to be

neutralised along with Russia, Austria would be free to support Germany on the

Western Front. On 28 October, with Friuli ‘ablaze from end to end’, Britain and

France agreed to send troops. Robertson and Foch, the respective chiefs of

staff, offered six divisions: hardly enough to bail out their ally, but

sufficient to bolster the defence and buy London and Paris political leverage

that could be used to unseat the generalissimo.

The deed was done at an inter-Allied meeting in Rapallo, on

6 November. General Porro’s presentation dismayed the British and French; his

vagueness about the facts of the situation and his pessimism confirmed that

change at the top was overdue. There was even talk of retreating beyond the

Piave to the River Mincio, losing the whole of the Veneto. In a stinging rebuff

to the Supreme Command, and specifically to Cadorna’s allegations of 28

October, the British stated that they were ready to trust their troops to the

bravery of the Italian soldiers but not to the efficiency of their commanders.

When Porro tried to speak, Foch told him to shut up. On behalf of Britain and

France, Lloyd George insisted on ‘the immediate riddance of Cadorna’. This gave

cover to Orlando’s government of ‘national resistance’, which wanted Cadorna to

go but feared a showdown. In return for an Italian pledge to hold the line on

the Piave, the British and French increased their promised support to five and

six divisions respectively.

As the flood of Italian troops ebbed towards the Piave and

the Supreme Command reasserted control over shattered units, the Central Powers

made errors. Instead of striking from the north-west as von Below and Boroević

swept in from the east, Conrad’s underpowered army advanced to the southern

edge of the Asiago plateau and no further. The Krauss Corps was sent north to

secure Carnia instead of pursuing the Italians westward.

After the war, Hindenburg described his disappointment over

Caporetto. ‘At the last the great victory had not been consummated.’ Krauss

accused Boroević of failing to clinch victory over the Third Army. These

recriminations reflect the bitterness of overall defeat in the World War, which

made Caporetto look like a missed opportunity. Piero Pieri, the first notable

historian of the Italian war, put his finger on the problem: the Central Powers

had, on this occasion, lacked ‘the annihilating mentality’.

King Victor Emanuel had his finest hour on 8 November,

rising to the moment with a speech affirming his faith in Italy’s destiny. That

day, the Second and Third Armies completed their crossing of the River Piave,

which was running high after heavy rain. At noon on the 9th, the engineers

dropped the bridges.

The new line lay some 150 kilometres west of the Isonzo. The

fulcrum of the line was a rugged massif called Grappa, some 20 kilometres

square. If Grappa fell, the Italians would be vulnerable both from the north

and the east. After the Austrian attack of May and June 1916, Cadorna had

planned to fortify Mount Grappa with roads, tunnels and trenches. In effect it

was the fifth defensive line from the Isonzo. Engineering in mountainous

terrain was what the Italian army did best, yet these works were hardly in hand

when the Twelfth Battle began: a single track and two cableways to the summit, a

water-pumping station, some barbed wire, and gun emplacements facing the wrong

way (westwards).

When the Krauss Corps and then von Below’s Fourteenth Army

hit the Grappa massif in mid-November, like the last blows of a sledgehammer,

the Italians were almost knocked back onto the plains. Conrad quipped that they

hung on to the south-western edge of Grappa like a man to a window-ledge. The

Supreme Command packed 50 battalions onto Grappa – around 50,000 men, including

many recruits from the latest draft class. The ensuing struggle was a battle in

itself; the situation was only saved at the end of December, with timely help

from a French division – the Allies’ sole active contribution to the defence

after Caporetto. This achievement gave birth to two new, much-needed myths: the

defence of Mount Grappa was acclaimed as a victory that saved the kingdom, and

the ‘boys of ’99’, sent straight from training to perform miracles, proved that

Italian fighting mettle was alive and well.

Foch and Robertson would have preferred the Duke of Aosta to

replace Cadorna. This was said to be inappropriate because the Duke was a

cousin of the King; in truth, it was impossible because Victor Emanuel loathed

his tall, handsome cousin. So they accepted the government’s proposal of General

Armando Diaz, with Badoglio and Giardino as joint deputies.

Diaz, a 57-year-old Neapolitan, had risen steadily through

the ranks. After the Libyan war, in which he showed a rare talent for winning

the affection and respect of his regiment, he served as General Pollio’s chef

de cabinet. After a year in the Supreme Command, he asked to be sent to the

front, where his calm good humour was noticed by the King, among others. He led

the XXIII Corps on the Carso with no particular distinction. A brother general

described him as a fine man and a good soldier but completely adaptable, ‘like

pasta’, with no ideas of his own. Cadorna’s court journalists scoffed at the

appointment, and Gatti was withering (‘Who knows Diaz?’).

Diaz would vindicate the King’s trust. News of his

promotion, on 8 November, struck him like a bolt of lightning. Accepting the

‘sacred duty’, he said: ‘You are ordering me to fight with a broken sword. Very

well, we shall fight all the same.’ And fight he did, though in a different way

from his predecessor. He proved to be an exceptional administrator and skilful

mediator, reconciling the government and the Supreme Command to each other, and

rival generals to his own appointment. Journalists were told that ‘with this

man, there will be no dangerous independence. State operations will be kept

united at all times.’ In other words, no more ‘government in Udine’. His first

statement to the troops urged them to fight for their land, home, family and

honour – in that order. He was what the army and the country needed after

Cadorna, and while he showed no brilliance as a strategist, he made no crucial

mistakes and took the decisions that led to victory.

On 7 November, hosting his last supper at the Supreme

Command, Cadorna addressed posterity over the plates: ‘I, with my will and my

fist, created and sustained this organism, this army of 3,000,000 men, until

yesterday. If I had not done it, we would never have made our voice heard in

Europe …’ Early the following day, the King arrived to persuade Cadorna to

leave quietly. They conferred for two hours. Cadorna knew he could not survive,

yet the humiliation was too much. There was no graceful exit. Diaz arrived late

that evening. When he presented a letter from the minister of war announcing

his appointment as chief of staff with immediate effect, Cadorna broke off the

meeting and telegraphed the minister: he would not go without a written

dismissal. The order arrived early next morning. A new regime took over at the

Supreme Command.

The phrase ‘doing a Cadorna’ became British soldiers’ slang

for coming unstuck, perpetrating an utter fuck-up and paying the price.

The statistics of defeat were dizzying. The Italians lost

nearly 12,000 dead, 30,000 wounded and 294,000 prisoners. In addition, there

were 350,000 disbanded men, roaming around or making for home. Only half of the

army’s 65 divisions survived intact, and half the artillery had been lost: more

than 3,000 guns, as well as 300,000 rifles, 3,000 machine guns, 1,600 motor

vehicles and so forth. Territorially, some 14,000 square kilometres were lost,

with a population of 1,150,000 people.

The Austro-German offensive was prepared with a

meticulousness that the Supreme Command could hardly imagine. The execution,

too, was incomparably efficient. Cadorna’s general method, as he once explained

to the King, was to use as many troops as possible along a sector as broad as

possible, hoping the enemy lines would crack somewhere. The Italian insistence

on retaining centralised control at senior levels was also archaic beside the

German devolution of authority to assault team level. Caporetto was the outcome

when innovative tactics were expertly used against an army that was, in

doctrine and organisation, one of the most hidebound in Europe.

The Twelfth Battle was a Blitzkrieg before the concept

existed. An Austrian officer who fought in the Krauss Corps described the

assault on 24 October as a fist punching through a barrier, then unclenching to

spread its fingers. This is very like a recent description of Blitzkrieg as

resembling ‘a shaped charge, penetrating through a relatively tiny hole in a

tank’s armor and then exploding outwardly to achieve a maximum cone of damage

against the unarmored or less protected innards’. Those innards had, in the

Italian case, been weakened by a combination of savage discipline, mediocre

leadership, second-rate equipment and arduous terrain. Without this

debilitation, the Second Army would not have collapsed almost on impact.

Naturally, Cadorna could not see or accept that he had undermined

the troops. But he knew that others would make this charge, which is why he

launched, pre-emptively, the self-serving myth that traitors and cowards were

responsible for the defeat. This myth became Cadorna’s most durable legacy,

thanks in part to a prompt endorsement by Leonida Bissolati, the cabinet

minister. Adding a nuance to Cadorna’s lie, Bissolati claimed that a sort of

‘military strike’ had taken place. Probably he was scoring points against his

rivals on the political left; instead he deepened a stain on the army that

still lingers. By likening the events on the Isonzo to the recent workers’

protests in Turin, Bissolati put a political complexion on the defeat. The ease

with which discipline was restored by the end of 1917 would have scotched these

allegations if it had not suited Italy’s leaders to keep them alive. It also

suited the Allies, who wanted to minimise the responsibility of their Italian

colleagues and had their own doubts about Italian martial spirit. Ambassador

Rodd and General Delmé-Radcliffe parroted the conspiracy theory in their

reports to London. For the historian George Trevelyan, leading the British Red

Cross volunteers who retreated with the Third Army, there was ‘positive

treachery at Caporetto’; Cadorna’s infamous bulletin had told the salutary

truth. For the novelist John Buchan, working as a senior propagandist in

London, treachery had ‘contributed to the disaster’, for a ‘secret campaign was

conducted throughout Italy’ in 1917, producing a ‘poison’ that ‘infected certain

parts of the army to an extent of which the military authorities were wholly

ignorant’.

For some, a more dreadful possibility underlay these

accusations. Was ‘Italy’ a middle-class illusion? Instead of forging a stronger

nation-state, the furnace of war had almost dissolved it. What would happen at

the next test? Disaffection with the state might be wider and deeper than they

had thought possible. Had the mass of Italians somehow been left out of the

nation-building process? If so, what further disasters still lay in store? It

was a moment when everything solid seemed to melt away. The philosopher Croce,

usually imperturbable to a fault, wrote during the Twelfth Battle: ‘The fate of

Italy is being decided for centuries to come.’ Even politicians who did not

swallow the ‘military strike’ thesis, and knew that Socialist members of

parliament were too patriotic to want peace at any price, feared the outcome if

popular disaffection became politically focused. After all, Lenin had taken

power in Russia in early November. For weeks after Caporetto, many officials

believed that revolution or sheer exhaustion would force Italy out of the war.

This mood of shaken self-questioning subsided as the army

was rebuilt in late 1917 and early 1918. It would be driven underground, into

the national unconscious, first by the victories of 1918, then by Fascist

suppression. Yet those who took part never forgot the fearful dreamlike days

when the world turned upside down. For the essence of Caporetto lay in the

wrenching uncertainty of late October, when the commanders did not know what

was happening, the officers did not know what to do, the soldiers did not know

where the enemy was, the government did not know if Italy was on the brink of

losing the war, and ordinary citizens did not know if their country might cease

to exist. All Italians dreamed that dream; the nation was haunted by an image

of men fleeing the front in hundreds of thousands, throwing away their rifles,

overcome by disgust with the army, the state and all its works, wanting nothing

more (or less) than to go home. When the anti-fascist Piero Gobetti wrote in

the 1920s that the Italians were still ‘a people of stragglers, not yet a

nation’, he evoked that fortnight when the country threatened to come apart at the

seams.

Under Mussolini, the myth of a military strike was

discouraged; it undermined the Fascists’ very different myth of the war as the

foundation of modern Italy, a blood rite that re-created the nation. The fact

of defeat at Caporetto had to be swallowed: a sour pill that could be sweetened

by blaming the government’s weakness. Fascist accounts of the Twelfth Battle

tended to whitewash Cadorna and defend the honour of the army (‘great even in

misfortune’) while incriminating Capello and indicting the government in Rome

for tolerating defeatists, profiteers and bourgeois draft-dodgers. Boselli

(‘tearful helmsman of the ship of state’) and his successor Orlando were

particularly lampooned. One valiant historian in the 1930s turned the narrative

of defeat inside out by hailing Caporetto as a deliberate trap set and sprung

by Cadorna, ‘the greatest strategist of our times’. The Duce himself called

Caporetto ‘a reverse’ that was ‘absolutely military in nature’, produced by ‘an

initial tactical success of the enemy’. Britain and France could also be

condemned for recalling, in early October 1917, most of the 140 guns they had

lent Cadorna earlier in the year. Even so, the defeat was not to be examined

too closely. When Colonel Gatti wanted to write a history of Caporetto, in

1925, Mussolini granted access to the archives in the Ministry of War. Then he

had second thoughts; summoning Gatti to Rome, he said it was a time for myths,

not history. After 1945, leftist historians argued that large parts of the army

had indeed ‘gone on strike’, not due to cowardice or socialism, but as a

spontaneous rebellion against the war as it was led by Cadorna and the

government.

That primal fear of dissolution survives in metaphor.

Corruption scandals are still branded ‘a moral Caporetto’. Politicians accuse

each other of facing an ‘electoral Caporetto’. When small businesses are

snarled up in Italy’s notorious red tape, they complain about an

‘administrative Caporetto’. When England lost to Northern Ireland at football,

it was ‘the English Caporetto’. This figure of speech stands for more than

simple defeat; it involves a hint of stomach-churning exposure – rottenness

laid bare.